Difference between revisions of "Jātaka"

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

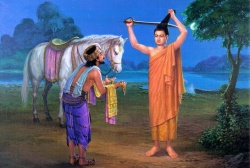

[[Jātaka]] means ‘about [[birth]]’ and is the [[Name]] of a [[book]] in the [[Khuddaka Nikāya]], the fifth part of the [[Sutta Piṭaka]] which is the first division of the [[Tipiṭaka]], the [[sacred]] [[scriptures]] of [[Buddhism]]. The [[Jātaka]] consists of 547 stories – some quite brief, others very long – illustrating [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|virtues}} like [[Kindness]], prudence, [[honesty]], {{Wiki|self}}-{{Wiki|sacrifice}}, {{Wiki|courage}} and {{Wiki|determination}}. The characters in many of the stories are [[Animals]]. The early [[Buddhists]] culled many of these stories from the great [[store]] of [[Indian]] {{Wiki|folklore}} and fables and made them [[Buddhist]] by saying that the [[hero]] of each story was actually The [[Buddha]] in one of his former [[lives]] as a [[Bodhisattva]]. Other stories are purely [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|creations}}. | [[Jātaka]] means ‘about [[birth]]’ and is the [[Name]] of a [[book]] in the [[Khuddaka Nikāya]], the fifth part of the [[Sutta Piṭaka]] which is the first division of the [[Tipiṭaka]], the [[sacred]] [[scriptures]] of [[Buddhism]]. The [[Jātaka]] consists of 547 stories – some quite brief, others very long – illustrating [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|virtues}} like [[Kindness]], prudence, [[honesty]], {{Wiki|self}}-{{Wiki|sacrifice}}, {{Wiki|courage}} and {{Wiki|determination}}. The characters in many of the stories are [[Animals]]. The early [[Buddhists]] culled many of these stories from the great [[store]] of [[Indian]] {{Wiki|folklore}} and fables and made them [[Buddhist]] by saying that the [[hero]] of each story was actually The [[Buddha]] in one of his former [[lives]] as a [[Bodhisattva]]. Other stories are purely [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|creations}}. | ||

The [[Jātaka]] consists of four parts. Preceding all the stories is a long introduction (''[[nidānakathā]]''), which relates tells the [[traditional]] [[life of the Buddha]] from his [[aspiration]] to become a [[Buddha]] up to the founding of the first [[Monastery]]. Each story is prefaced by a ‘story of the present’ (''[[paccuppanna vaṇṇa]]''), giving the [[reasons]] why The [[Buddha]] told the story, and ends with a ‘connection’ (''[[samodhāna]]'') in which the characters in the story are identified. The stories themselves ([[atīta vatthu]]) are in prose and imbedded within them are verses (''[[gāthā]]''), of which there are about 2500 altogether. Only these verses are considered the actual words of The [[Buddha]]. With their lively plots, well-defined characters and flashes of humor, the [[Jātaka]] has long been one of the most popular [[Books]] in the [[scriptures]]. {{Wiki|Scholars}} believe that some of the fables of Aesop and many other [[collections]] of {{Wiki|folklore}} have their origins in the [[Jātaka]]. | The [[Jātaka]] consists of four parts. Preceding all the stories is a long introduction (''[[nidānakathā]]''), which relates tells the [[traditional]] [[life of the Buddha]] from his [[aspiration]] to become a [[Buddha]] up to the founding of the first [[Monastery]]. Each story is prefaced by a ‘story of the present’ (''[[paccuppanna vaṇṇa]]''), giving the [[reasons]] why The [[Buddha]] told the story, and ends with a ‘connection’ (''[[samodhāna]]'') in which the characters in the story are identified. The stories themselves ([[atīta vatthu]]) are in prose and imbedded within them are verses (''[[gāthā]]''), of which there are about 2500 altogether. Only these verses are considered the actual words of The [[Buddha]]. With their lively plots, well-defined characters and flashes of humor, the [[Jātaka]] has long been one of the most popular [[Books]] in the [[scriptures]]. {{Wiki|Scholars}} believe that some of the fables of Aesop and many other [[collections]] of {{Wiki|folklore}} have their origins in the [[Jātaka]]. | ||

| − | + | [[File:Bangladesh Prayer.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

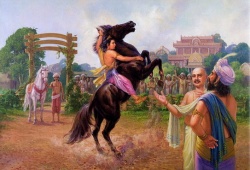

The [[Jātakas]] ([[Sanskrit]] जातक) (also known in other {{Wiki|languages}} as: {{Wiki|Burmese}}: ဇာတ်တော်, pronounced: [zaʔ tɔ̀]; Khmer: ជាតក [cietɑk]; Lao: ຊາດົກ sadok; [[Thai]]: ชาดก chadok) refer to a voluminous [[body]] of {{Wiki|literature}} native to {{Wiki|India}} concerning the previous {{Wiki|births}} ([[jāti]]) of the {{Wiki|Bodhisattva}}. These are the stories that tell about the previous [[lives]] of the {{Wiki|Buddha}}, in both [[human]] and [[animal]] [[form]]. The future [[Buddha]] may appear in them as a [[king]], an outcast, a [[god]], an elephant—but, in whatever [[form]], he exhibits some [[virtue]] that the tale thereby inculcates. | The [[Jātakas]] ([[Sanskrit]] जातक) (also known in other {{Wiki|languages}} as: {{Wiki|Burmese}}: ဇာတ်တော်, pronounced: [zaʔ tɔ̀]; Khmer: ជាតក [cietɑk]; Lao: ຊາດົກ sadok; [[Thai]]: ชาดก chadok) refer to a voluminous [[body]] of {{Wiki|literature}} native to {{Wiki|India}} concerning the previous {{Wiki|births}} ([[jāti]]) of the {{Wiki|Bodhisattva}}. These are the stories that tell about the previous [[lives]] of the {{Wiki|Buddha}}, in both [[human]] and [[animal]] [[form]]. The future [[Buddha]] may appear in them as a [[king]], an outcast, a [[god]], an elephant—but, in whatever [[form]], he exhibits some [[virtue]] that the tale thereby inculcates. | ||

| − | + | [[File:0444vn.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

In [[Theravada]] [[Buddhism]], the [[Jatakas]] are a textual division of the [[Pali Canon]], included in the [[Khuddaka Nikaya]] of the [[Sutta Pitaka]]. The term [[Jataka]] may also refer to a [[traditional]] commentary on this [[book]]. | In [[Theravada]] [[Buddhism]], the [[Jatakas]] are a textual division of the [[Pali Canon]], included in the [[Khuddaka Nikaya]] of the [[Sutta Pitaka]]. The term [[Jataka]] may also refer to a [[traditional]] commentary on this [[book]]. | ||

[[File:Buddha444.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha444.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

{{Wiki|History}} | {{Wiki|History}} | ||

| − | + | [[File:Bahuchara.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

The [[Jatakas]] were originally amongst the earliest [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|literature}}, with metrical [[analysis]] methods dating their average contents to around the 4th century BCE. The [[Mahāsāṃghika Caitika]] sects from the {{Wiki|Āndhra}} region took the [[Jatakas]] as {{Wiki|canonical}} {{Wiki|literature}}, and are known to have rejected some of the [[Theravada]] [[Jatakas]] which dated past the [[time]] of [[King]] [[Ashoka]]. The [[Caitikas]] claimed that their own [[Jatakas]] represented the original collection before the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] split into various [[lineages]]. | The [[Jatakas]] were originally amongst the earliest [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|literature}}, with metrical [[analysis]] methods dating their average contents to around the 4th century BCE. The [[Mahāsāṃghika Caitika]] sects from the {{Wiki|Āndhra}} region took the [[Jatakas]] as {{Wiki|canonical}} {{Wiki|literature}}, and are known to have rejected some of the [[Theravada]] [[Jatakas]] which dated past the [[time]] of [[King]] [[Ashoka]]. The [[Caitikas]] claimed that their own [[Jatakas]] represented the original collection before the [[Buddhist]] [[tradition]] split into various [[lineages]]. | ||

| − | + | [[File:0440vn.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | |

According to {{Wiki|A.K. Warder}}, the [[Jatakas]] are the precursors to the various legendary {{Wiki|biographies}} of the [[Buddha]], which were composed at later dates. Although many [[Jatakas]] were written from an early period, which describe previous [[lives]] of the [[Buddha]], very little biographical {{Wiki|material}} about [[Gautama]]'s own [[life]] has been recorded. | According to {{Wiki|A.K. Warder}}, the [[Jatakas]] are the precursors to the various legendary {{Wiki|biographies}} of the [[Buddha]], which were composed at later dates. Although many [[Jatakas]] were written from an early period, which describe previous [[lives]] of the [[Buddha]], very little biographical {{Wiki|material}} about [[Gautama]]'s own [[life]] has been recorded. | ||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

Contents | Contents | ||

| − | The [[Theravada]] [[Jatakas]] comprise 547 poems, arranged roughly by {{Wiki|increasing}} number of verses. According to {{Wiki|Professor}} von Hinüber, only the last 50 were intended to be intelligible by themselves, without commentary. The commentary gives stories in prose that it claims provide the context for the verses, and it is these stories that are of [[interest]] to {{Wiki|folklorists}}. Alternative versions of some of the stories can be found in another [[book]] of the [[Pali Canon]], the [[Cariyapitaka]], and a number of {{Wiki|individual}} stories can be found scattered around other [[books]] of the {{Wiki|Canon}}. Many of the stories and motifs found in the [[Jataka]] such as the {{Wiki|Rabbit}} in the {{Wiki|Moon}} of the [[Śaśajâtaka]] ([[Jataka Tales]]: no.316) are found in numerous other languages and media. For example, The {{Wiki|Monkey}} and the Crocodile, The [[Turtle]] Who Couldn't Stop Talking and The Crab and the Crane that are listed below also famously feature in the {{Wiki|Hindu}} {{Wiki|Panchatantra}}, the [[Sanskrit]] [[niti-shastra]] that ubiquitously influenced [[world]] {{Wiki|literature}}. Many of the stories and motifs {{Wiki|being}} translations from the [[Pali]] but others are instead derived from vernacular oral [[traditions]] prior to the [[Pali]] compositions. | + | The [[Theravada]] [[Jatakas]] comprise 547 poems, arranged roughly by {{Wiki|increasing}} number of verses. According to {{Wiki|Professor}} von Hinüber, only the last 50 were intended to be intelligible by themselves, without commentary. The commentary gives stories in prose that it claims provide the context for the verses, and it is these stories that are of [[interest]] to {{Wiki|folklorists}}. Alternative versions of some of the stories can be found in another [[book]] of the [[Pali Canon]], the [[Cariyapitaka]], and a number of {{Wiki|individual}} stories can be found scattered around other [[books]] of the {{Wiki|Canon}}. Many of the stories and motifs found in the [[Jataka]] such as the {{Wiki|Rabbit}} in the {{Wiki|Moon}} of the [[Śaśajâtaka]] ([[Jataka Tales]]: no.316) are found in numerous other [[languages]] and media. For example, The {{Wiki|Monkey}} and the Crocodile, The [[Turtle]] Who Couldn't Stop Talking and The Crab and the Crane that are listed below also famously feature in the {{Wiki|Hindu}} {{Wiki|Panchatantra}}, the [[Sanskrit]] [[niti-shastra]] that ubiquitously influenced [[world]] {{Wiki|literature}}. Many of the stories and motifs {{Wiki|being}} translations from the [[Pali]] but others are instead derived from vernacular oral [[traditions]] prior to the [[Pali]] compositions. |

[[File:Budgfj4.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Budgfj4.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Sanskrit]] (see for example the [[Jatakamala]]) and {{Wiki|Tibetan}} [[Jataka]] stories tend to maintain the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|morality}} of their [[Pali]] equivalents, but re-tellings of the stories in Persian and other languages sometimes contain significant amendments to suit their respective cultures. | + | [[Sanskrit]] (see for example the [[Jatakamala]]) and {{Wiki|Tibetan}} [[Jataka]] stories tend to maintain the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|morality}} of their [[Pali]] equivalents, but re-tellings of the stories in Persian and other [[languages]] sometimes contain significant amendments to suit their respective cultures. |

Apocrypha | Apocrypha | ||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

The standard [[Pali]] collection of [[jatakas]], with {{Wiki|canonical}} text embedded, has been translated by E. B. Cowell and others, originally published in six volumes by {{Wiki|Cambridge}} {{Wiki|University}} Press, 1895-1907; reprinted in three volumes, [[Pali]] Text {{Wiki|Society}}, Bristol. There are also numerous translations of selections and {{Wiki|individual}} stories from various [[languages]]. | The standard [[Pali]] collection of [[jatakas]], with {{Wiki|canonical}} text embedded, has been translated by E. B. Cowell and others, originally published in six volumes by {{Wiki|Cambridge}} {{Wiki|University}} Press, 1895-1907; reprinted in three volumes, [[Pali]] Text {{Wiki|Society}}, Bristol. There are also numerous translations of selections and {{Wiki|individual}} stories from various [[languages]]. | ||

[[File:Burma.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Burma.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Jacobs, Joseph (1888), The earliest English version of the Fables of Bidpai, {{Wiki|London}} Google [[Books]] (edited and induced from The Morall Philosophie of Doni by Sir Thomas {{Wiki|North}}, 1570) | + | Jacobs, Joseph (1888), The earliest {{Wiki|English}} version of the Fables of Bidpai, {{Wiki|London}} Google [[Books]] (edited and induced from The Morall Philosophie of Doni by Sir Thomas {{Wiki|North}}, 1570) |

List of [[Jatakas]] | List of [[Jatakas]] | ||

| Line 49: | Line 49: | ||

The [[Elephant]] Girly-Face | The [[Elephant]] Girly-Face | ||

The [[Foolish]], Timid {{Wiki|Rabbit}} | The [[Foolish]], Timid {{Wiki|Rabbit}} | ||

| − | The Great Ape | + | The [[Great]] Ape |

The King's White [[Elephant]] | The King's White [[Elephant]] | ||

The [[Lion]], the Bear and the [[Fox]] | The [[Lion]], the Bear and the [[Fox]] | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

The Princes and the Water-Sprite | The Princes and the Water-Sprite | ||

The Quarrel of the Quails | The Quarrel of the Quails | ||

| − | The Sandy Road | + | The Sandy [[Road]] |

The {{Wiki|Tiger}}, the [[Brahmin]] and the Jackal | The {{Wiki|Tiger}}, the [[Brahmin]] and the Jackal | ||

The Tortoise and the Birds | The Tortoise and the Birds | ||

Revision as of 18:46, 16 September 2013

Jātaka means ‘about birth’ and is the Name of a book in the Khuddaka Nikāya, the fifth part of the Sutta Piṭaka which is the first division of the Tipiṭaka, the sacred scriptures of Buddhism. The Jātaka consists of 547 stories – some quite brief, others very long – illustrating Buddhist virtues like Kindness, prudence, honesty, self-sacrifice, courage and determination. The characters in many of the stories are Animals. The early Buddhists culled many of these stories from the great store of Indian folklore and fables and made them Buddhist by saying that the hero of each story was actually The Buddha in one of his former lives as a Bodhisattva. Other stories are purely Buddhist creations.

The Jātaka consists of four parts. Preceding all the stories is a long introduction (nidānakathā), which relates tells the traditional life of the Buddha from his aspiration to become a Buddha up to the founding of the first Monastery. Each story is prefaced by a ‘story of the present’ (paccuppanna vaṇṇa), giving the reasons why The Buddha told the story, and ends with a ‘connection’ (samodhāna) in which the characters in the story are identified. The stories themselves (atīta vatthu) are in prose and imbedded within them are verses (gāthā), of which there are about 2500 altogether. Only these verses are considered the actual words of The Buddha. With their lively plots, well-defined characters and flashes of humor, the Jātaka has long been one of the most popular Books in the scriptures. Scholars believe that some of the fables of Aesop and many other collections of folklore have their origins in the Jātaka.

The Jātakas (Sanskrit जातक) (also known in other languages as: Burmese: ဇာတ်တော်, pronounced: [zaʔ tɔ̀]; Khmer: ជាតក [cietɑk]; Lao: ຊາດົກ sadok; Thai: ชาดก chadok) refer to a voluminous body of literature native to India concerning the previous births (jāti) of the Bodhisattva. These are the stories that tell about the previous lives of the Buddha, in both human and animal form. The future Buddha may appear in them as a king, an outcast, a god, an elephant—but, in whatever form, he exhibits some virtue that the tale thereby inculcates.

In Theravada Buddhism, the Jatakas are a textual division of the Pali Canon, included in the Khuddaka Nikaya of the Sutta Pitaka. The term Jataka may also refer to a traditional commentary on this book.

The Jatakas were originally amongst the earliest Buddhist literature, with metrical analysis methods dating their average contents to around the 4th century BCE. The Mahāsāṃghika Caitika sects from the Āndhra region took the Jatakas as canonical literature, and are known to have rejected some of the Theravada Jatakas which dated past the time of King Ashoka. The Caitikas claimed that their own Jatakas represented the original collection before the Buddhist tradition split into various lineages.

According to A.K. Warder, the Jatakas are the precursors to the various legendary biographies of the Buddha, which were composed at later dates. Although many Jatakas were written from an early period, which describe previous lives of the Buddha, very little biographical material about Gautama's own life has been recorded.

The Jataka-Mala of Arya Shura in Sanskrit gives 34 Jataka stories . At Ajanta, Jataka scenes are inscribed with quotes from Arya Shura , with script datable to sixth century. It had already been translated into Chinese in 434 CE. Borobudur contains depictions of all 34 Jatakas from Jataka Mala .

Khudda-bodhi-Jataka, Borobudur

Contents

The Theravada Jatakas comprise 547 poems, arranged roughly by increasing number of verses. According to Professor von Hinüber, only the last 50 were intended to be intelligible by themselves, without commentary. The commentary gives stories in prose that it claims provide the context for the verses, and it is these stories that are of interest to folklorists. Alternative versions of some of the stories can be found in another book of the Pali Canon, the Cariyapitaka, and a number of individual stories can be found scattered around other books of the Canon. Many of the stories and motifs found in the Jataka such as the Rabbit in the Moon of the Śaśajâtaka (Jataka Tales: no.316) are found in numerous other languages and media. For example, The Monkey and the Crocodile, The Turtle Who Couldn't Stop Talking and The Crab and the Crane that are listed below also famously feature in the Hindu Panchatantra, the Sanskrit niti-shastra that ubiquitously influenced world literature. Many of the stories and motifs being translations from the Pali but others are instead derived from vernacular oral traditions prior to the Pali compositions.

Sanskrit (see for example the Jatakamala) and Tibetan Jataka stories tend to maintain the Buddhist morality of their Pali equivalents, but re-tellings of the stories in Persian and other languages sometimes contain significant amendments to suit their respective cultures.

Apocrypha

Within the Pali tradition, there are also many apocryphal Jatakas of later composition (some dated even to the 19th century) but these are treated as a separate category of literature from the "Official" Jataka stories that have been more-or-less formally canonized from at least the 5th century — as attested to in ample epigraphic and archaeological evidence, such as extant illustrations in bas relief from ancient temple walls.

Apocryphal Jatakas of the Pali Buddhist canon, such as those belonging to the Paññāsajātaka collection, have been adapted to fit local culture in certain South East Asian countries and have been retold with amendments to the plots to better reflect Buddhist morals.

Celebrations and ceremonies

In Theravada countries several of the longer Jatakas such as Rathasena Jataka and Vessantara Jataka, are still performed in dance, theatre, and formal (quasi-ritual) recitation. Such celebrations are associated with particular holidays on the lunar calendar used by Cambodia, Thailand and Laos.

Translations

The standard Pali collection of jatakas, with canonical text embedded, has been translated by E. B. Cowell and others, originally published in six volumes by Cambridge University Press, 1895-1907; reprinted in three volumes, Pali Text Society, Bristol. There are also numerous translations of selections and individual stories from various languages.

Jacobs, Joseph (1888), The earliest English version of the Fables of Bidpai, London Google Books (edited and induced from The Morall Philosophie of Doni by Sir Thomas North, 1570)

List of Jatakas

This list includes stories based on the Jatakas:

Grannie's Blackie

How the Turtle Saved His Own Life

Prince Sattva

Sibi Jataka

The Ass and the Pig

The Ass in the Lion's Skin

The Banyan Deer

The Crab and the Crane

The Elephant Girly-Face

The Foolish, Timid Rabbit

The Great Ape

The King's White Elephant

The Lion, the Bear and the Fox

The Measure of Rice

The Merchant of Seri

The Monkey and the Crocodile

The Ox Who Envied the Pig

The Ox Who Won the Forfeit

The Princes and the Water-Sprite

The Quarrel of the Quails

The Sandy Road

The Tiger, the Brahmin and the Jackal

The Tortoise and the Birds

The Turtle Who Couldn't Stop Talking

The Twelve Sisters

The Wise and the Foolish Merchant

Vessantara Jataka

Why the Owl Is Not King of the Birds

The Jātaka, trans. by R. Chalmers, H.T. Francis, E.B. Cowell and W.H.D. Rouse, 1990.