Difference between revisions of "Buddhism in China: The First Thousand Years"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> Buddhism first reached China from India roughly 2,000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty. Han Dynasty China was deeply Confucia...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

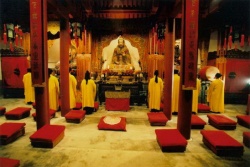

[[File:Huayan-Mona244.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huayan-Mona244.jpeg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | Buddhism first reached China from India roughly 2,000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty. Han Dynasty China was deeply Confucian, and Confucianism is focused on maintaining harmony and social order in the here-and-now world. Buddhism, on the other hand, emphasized entering the monastic life to seek a reality beyond reality. Confucian China was not terribly friendly to Buddhism. | + | [[Buddhism]] first reached [[China]] from [[India]] roughly 2,000 years ago, during the {{Wiki|Han Dynasty}}. {{Wiki|Han Dynasty}} [[China]] was deeply {{Wiki|Confucian}}, and {{Wiki|Confucianism}} is focused on maintaining [[harmony]] and {{Wiki|social}} [[order]] in the here-and-now [[world]]. [[Buddhism]], on the other hand, emphasized entering the [[monastic]] [[life]] to seek a [[reality]] [[beyond]] [[reality]]. {{Wiki|Confucian}} [[China]] was not terribly friendly to [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | However, Buddhism found an ally in China's other indigenous religion, Taoism. Taoist and Buddhist meditation practices and philosophies were similar in many respects, and some Chinese took an interest in Buddhism from a Taoist perspective. Early translations of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit into Chinese borrowed Taoist terminology. Still, during the Han Dynasty very few Chinese practiced Buddhism. | + | However, [[Buddhism]] found an ally in China's other indigenous [[religion]], {{Wiki|Taoism}}. {{Wiki|Taoist}} and [[Buddhist meditation]] practices and [[philosophies]] were similar in many respects, and some {{Wiki|Chinese}} took an [[interest]] in [[Buddhism]] from a {{Wiki|Taoist}} {{Wiki|perspective}}. Early translations of [[Buddhist texts]] from [[Sanskrit]] into {{Wiki|Chinese}} borrowed {{Wiki|Taoist}} {{Wiki|terminology}}. Still, during the {{Wiki|Han Dynasty}} very few {{Wiki|Chinese}} practiced [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | Buddhism in China: Early Gains and Losses | + | [[Buddhism in China]]: Early Gains and Losses |

| − | The Han Dynasty fell in 220, beginning a period of social and political chaos in China. The northern part of China was overrun by non-Chinese tribes, and the southern part was ruled by a succession of weak dynasties. This chaos also weakened the hold of Confucianism among the ruling class. | + | The {{Wiki|Han Dynasty}} fell in 220, beginning a period of {{Wiki|social}} and {{Wiki|political}} {{Wiki|chaos}} in [[China]]. The northern part of [[China]] was overrun by non-Chinese tribes, and the southern part was ruled by a succession of weak dynasties. This {{Wiki|chaos}} also weakened the hold of {{Wiki|Confucianism}} among the ruling class. |

| − | In south China, a kind of "gentry Buddhism" became popular among educated Chinese that stressed learning and philosophy. The elite of Chinese society freely associated with the growing number of Buddhist monks and scholars. The dialog between Buddhism and Taoism continued, and the Taoist influence caused the Chinese to favor Mahayana over Theravada Buddhism. | + | In {{Wiki|south}} [[China]], a kind of "gentry [[Buddhism]]" became popular among educated {{Wiki|Chinese}} that stressed {{Wiki|learning}} and [[philosophy]]. The elite of {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|society}} freely associated with the growing number of [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] and [[scholars]]. The dialog between [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Taoism}} continued, and the {{Wiki|Taoist}} [[influence]] [[caused]] the {{Wiki|Chinese}} to favor [[Mahayana]] over [[Theravada Buddhism]]. |

| − | In north China, Buddhist monks who were masters of divination became advisers to rulers of the "barbarian" tribes. Some of these rulers became Buddhists and supported monasteries and the ongoing work of translating the Sanskrit texts into Chinese. This separation of north and south China caused Buddhism to develop into northern and southern schools in China. | + | In {{Wiki|north}} [[China]], [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] who were [[masters]] of [[divination]] became advisers to rulers of the "barbarian" tribes. Some of these rulers became [[Buddhists]] and supported [[monasteries]] and the ongoing work of translating the [[Sanskrit]] texts into {{Wiki|Chinese}}. This separation of {{Wiki|north}} and {{Wiki|south}} [[China]] [[caused]] [[Buddhism]] to develop into northern and southern schools in [[China]]. |

| − | In the 5th century, the Wei dynasty of northern China absorbed the other tribes, and by 440 it controlled all of northern China. In 446 the Wei ruler, Emperor Taiwu, began a brutal suppression of Buddhism -- all Buddhist temples, texts and art were to be destroyed, and the monks were to be executed. At least some part of the northern sangha hid from authorities and escaped execution, however. | + | In the 5th century, the Wei dynasty of northern [[China]] absorbed the other tribes, and by 440 it controlled all of northern [[China]]. In 446 the Wei ruler, [[Emperor]] Taiwu, began a brutal suppression of [[Buddhism]] -- all [[Buddhist]] [[temples]], texts and [[art]] were to be destroyed, and the [[monks]] were to be executed. At least some part of the northern [[sangha]] hid from authorities and escaped execution, however. |

| − | Taiwu died in 452; his successor, Emperor Wencheng, ended the suppression and began a restoration of Buddhism that included sculpting of the magnificent grottoes of Yungang. | + | Taiwu [[died]] in 452; his successor, [[Emperor]] [[Wencheng]], ended the suppression and began a restoration of [[Buddhism]] that included sculpting of the magnificent [[grottoes]] of Yungang. |

| − | Buddhism in China: Major Schools | + | [[Buddhism in China]]: Major Schools |

| − | Here are just four of the schools of Mahayana Buddhism that emerged in China: | + | Here are just four of the schools of [[Mahayana Buddhism]] that emerged in [[China]]: |

| − | In 402 CE the monk and teacher Hui-yuan (336-416) established the White Lotus Society at Mount Lushan in southeast China. This was the beginning of the Pure Land school of Buddhism. Pure Land eventually would become popular throughout large parts of Asia. Today it is the dominant form of Buddhism in Japan. | + | In 402 CE the [[monk]] and [[teacher]] [[Hui-yuan]] (336-416) established the [[White Lotus]] {{Wiki|Society}} at Mount Lushan in {{Wiki|southeast}} [[China]]. This was the beginning of the [[Pure Land]] school of [[Buddhism]]. [[Pure Land]] eventually would become popular throughout large parts of {{Wiki|Asia}}. Today it is the dominant [[form]] of [[Buddhism in Japan]]. |

[[File:Huayan-t012.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huayan-t012.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | About the year 500, an Indian sage named Bodhidharma (ca. 470-543) arrived in China. At the Shaolin Monastery in what is now Henan Province, Bodhidharma founded the Ch'an school of Buddhism, better known in the West by its Japanese name, Zen. | + | About the year 500, an [[Indian]] [[sage]] named [[Bodhidharma]] (ca. 470-543) arrived in [[China]]. At the [[Shaolin]] [[Monastery]] in what is now Henan Province, [[Bodhidharma]] founded the [[Ch'an]] school of [[Buddhism]], better known in the {{Wiki|West}} by its [[Japanese]] [[name]], [[Zen]]. |

| − | Tiantai emerged as a distinctive school through the teachings of Zhiyi (also spelled Chih-i, 538-597). Along with being a major school in its own right, Tiantai's emphasis on the Lotus Sutra influenced other schools of Buddhism. | + | [[Tiantai]] emerged as a {{Wiki|distinctive}} school through the teachings of [[Zhiyi]] (also spelled [[Chih-i]], 538-597). Along with {{Wiki|being}} a major school in its own right, Tiantai's emphasis on the [[Lotus Sutra]] influenced other [[schools of Buddhism]]. |

| − | Huayan (or Hua-Yen; Kegon in Japan) took shape under the guidance of its first three patriarchs: Tu-shun (557-640), Chih-yen (602-668) and Fa-tsang (or Fazang, 643-712). A large part of the teachings of this school were absorbed into Ch'an (Zen) during the T'ang Dynasty. | + | [[Huayan]] (or [[Hua-Yen]]; [[Kegon]] in [[Japan]]) took [[shape]] under the guidance of its first three [[patriarchs]]: [[Tu-shun]] (557-640), [[Chih-yen]] (602-668) and [[Fa-tsang]] (or [[Fazang]], 643-712). A large part of the teachings of this school were absorbed into [[Ch'an]] ([[Zen]]) during the T'ang Dynasty. |

| − | Buddhism in China: North and South Reunite | + | [[Buddhism in China]]: {{Wiki|North}} and {{Wiki|South}} Reunite |

| − | Northern and southern China reunited in 589 under the Sui emperor. After centuries of separation, northern and southern China had little in common other than Buddhism. The emperor gathered relics of the Buddha and had them enshrined in stupas throughout China as a symbolic gesture that China was one nation again. | + | Northern and southern [[China]] reunited in 589 under the Sui [[emperor]]. After centuries of separation, northern and southern [[China]] had little in common other than [[Buddhism]]. The [[emperor]] gathered [[relics]] of the [[Buddha]] and had them enshrined in [[stupas]] throughout [[China]] as a [[symbolic]] gesture that [[China]] was one nation again. |

| − | Buddhism in China: The T'ang Dynasty | + | [[Buddhism in China]]: The T'ang Dynasty |

| − | The influence of Buddhism in China reached its peak during the T'ang Dynasty, 618 to 907. Buddhist arts flourished, and monasteries grew rich and powerful. Some Confucians and Taoists thought Buddhism had become too rich and powerful, actually. Factional strife came to a head in 845, when the emperor began a suppression of Buddhism that destroyed more than 4,000 monasteries and 40,000 temples and shrines. | + | The [[influence]] of [[Buddhism in China]] reached its peak during the T'ang Dynasty, 618 to 907. [[Buddhist]] arts flourished, and [[monasteries]] grew rich and {{Wiki|powerful}}. Some Confucians and Taoists [[thought]] [[Buddhism]] had become too rich and {{Wiki|powerful}}, actually. Factional strife came to a {{Wiki|head}} in 845, when the [[emperor]] began a suppression of [[Buddhism]] that destroyed more than 4,000 [[monasteries]] and 40,000 [[temples]] and [[shrines]]. |

| − | This suppression dealt a crippling blow to Chinese Buddhism and marked the beginning of a long decline. Buddhism would never again be as dominant in China as it had been during the T'ang Dynasty. Even so, After a thousand years Buddhism thoroughly permeated Chinese culture and also influenced its rival religions, Confucianism and Taoism. | + | This suppression dealt a crippling blow to [[Chinese Buddhism]] and marked the beginning of a long {{Wiki|decline}}. [[Buddhism]] would never again be as dominant in [[China]] as it had been during the T'ang Dynasty. Even so, After a thousand years [[Buddhism]] thoroughly permeated {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|culture}} and also influenced its rival [[religions]], {{Wiki|Confucianism}} and {{Wiki|Taoism}}. |

| − | Of the several distinctive schools that had originated in China, only Pure Land and Ch'an survived the suppression with an appreciable number of followers. Tiantai flourished in Japan as Tendai. Huayan survives in Japan as Kegon. Huayan teachings also remain visible in Ch'an and Zen Buddhism. | + | Of the several {{Wiki|distinctive}} schools that had originated in [[China]], only [[Pure Land]] and [[Ch'an]] survived the suppression with an appreciable number of followers. [[Tiantai]] flourished in [[Japan]] as [[Tendai]]. [[Huayan]] survives in [[Japan]] as [[Kegon]]. [[Huayan]] teachings also remain [[visible]] in [[Ch'an]] and [[Zen]] [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | And as the first thousand years of Buddhism in China ended, the legends of the Laughing Buddha, called Budai or Pu-tai, emerged from Chinese folklore in the 10th century. This rotund character remains a favorite subject of Chinese art. | + | And as the first thousand years of [[Buddhism in China]] ended, the legends of the [[Laughing Buddha]], called [[Budai]] or Pu-tai, emerged from {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|folklore}} in the 10th century. This rotund [[character]] {{Wiki|remains}} a favorite [[subject]] of {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[art]]. |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

Latest revision as of 11:09, 17 September 2013

Buddhism first reached China from India roughly 2,000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty. Han Dynasty China was deeply Confucian, and Confucianism is focused on maintaining harmony and social order in the here-and-now world. Buddhism, on the other hand, emphasized entering the monastic life to seek a reality beyond reality. Confucian China was not terribly friendly to Buddhism.

However, Buddhism found an ally in China's other indigenous religion, Taoism. Taoist and Buddhist meditation practices and philosophies were similar in many respects, and some Chinese took an interest in Buddhism from a Taoist perspective. Early translations of Buddhist texts from Sanskrit into Chinese borrowed Taoist terminology. Still, during the Han Dynasty very few Chinese practiced Buddhism.

Buddhism in China: Early Gains and Losses

The Han Dynasty fell in 220, beginning a period of social and political chaos in China. The northern part of China was overrun by non-Chinese tribes, and the southern part was ruled by a succession of weak dynasties. This chaos also weakened the hold of Confucianism among the ruling class.

In south China, a kind of "gentry Buddhism" became popular among educated Chinese that stressed learning and philosophy. The elite of Chinese society freely associated with the growing number of Buddhist monks and scholars. The dialog between Buddhism and Taoism continued, and the Taoist influence caused the Chinese to favor Mahayana over Theravada Buddhism.

In north China, Buddhist monks who were masters of divination became advisers to rulers of the "barbarian" tribes. Some of these rulers became Buddhists and supported monasteries and the ongoing work of translating the Sanskrit texts into Chinese. This separation of north and south China caused Buddhism to develop into northern and southern schools in China.

In the 5th century, the Wei dynasty of northern China absorbed the other tribes, and by 440 it controlled all of northern China. In 446 the Wei ruler, Emperor Taiwu, began a brutal suppression of Buddhism -- all Buddhist temples, texts and art were to be destroyed, and the monks were to be executed. At least some part of the northern sangha hid from authorities and escaped execution, however.

Taiwu died in 452; his successor, Emperor Wencheng, ended the suppression and began a restoration of Buddhism that included sculpting of the magnificent grottoes of Yungang.

Buddhism in China: Major Schools

Here are just four of the schools of Mahayana Buddhism that emerged in China:

In 402 CE the monk and teacher Hui-yuan (336-416) established the White Lotus Society at Mount Lushan in southeast China. This was the beginning of the Pure Land school of Buddhism. Pure Land eventually would become popular throughout large parts of Asia. Today it is the dominant form of Buddhism in Japan.

About the year 500, an Indian sage named Bodhidharma (ca. 470-543) arrived in China. At the Shaolin Monastery in what is now Henan Province, Bodhidharma founded the Ch'an school of Buddhism, better known in the West by its Japanese name, Zen.

Tiantai emerged as a distinctive school through the teachings of Zhiyi (also spelled Chih-i, 538-597). Along with being a major school in its own right, Tiantai's emphasis on the Lotus Sutra influenced other schools of Buddhism.

Huayan (or Hua-Yen; Kegon in Japan) took shape under the guidance of its first three patriarchs: Tu-shun (557-640), Chih-yen (602-668) and Fa-tsang (or Fazang, 643-712). A large part of the teachings of this school were absorbed into Ch'an (Zen) during the T'ang Dynasty.

Buddhism in China: North and South Reunite

Northern and southern China reunited in 589 under the Sui emperor. After centuries of separation, northern and southern China had little in common other than Buddhism. The emperor gathered relics of the Buddha and had them enshrined in stupas throughout China as a symbolic gesture that China was one nation again.

Buddhism in China: The T'ang Dynasty

The influence of Buddhism in China reached its peak during the T'ang Dynasty, 618 to 907. Buddhist arts flourished, and monasteries grew rich and powerful. Some Confucians and Taoists thought Buddhism had become too rich and powerful, actually. Factional strife came to a head in 845, when the emperor began a suppression of Buddhism that destroyed more than 4,000 monasteries and 40,000 temples and shrines.

This suppression dealt a crippling blow to Chinese Buddhism and marked the beginning of a long decline. Buddhism would never again be as dominant in China as it had been during the T'ang Dynasty. Even so, After a thousand years Buddhism thoroughly permeated Chinese culture and also influenced its rival religions, Confucianism and Taoism.

Of the several distinctive schools that had originated in China, only Pure Land and Ch'an survived the suppression with an appreciable number of followers. Tiantai flourished in Japan as Tendai. Huayan survives in Japan as Kegon. Huayan teachings also remain visible in Ch'an and Zen Buddhism.

And as the first thousand years of Buddhism in China ended, the legends of the Laughing Buddha, called Budai or Pu-tai, emerged from Chinese folklore in the 10th century. This rotund character remains a favorite subject of Chinese art.