Difference between revisions of "Tiantai School"

m (1 revision: Robo replace 16sept) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:ChinaTiantai.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:ChinaTiantai.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | [[Tiantai]] (Chinese and Japanese: 天台宗; pinyin: tiāntāi zōng; ) is an important school of [[Buddhism in China]], [[Japan]], [[Korea]], and [[Vietnam]]. In [[Japan]] the school is known as [[Tendai]]-shū, and in [[Korea]] it is known as Cheontae. | + | [[Tiantai]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}} and [[Japanese]]: 天台宗; pinyin: tiāntāi zōng; ) is an important school of [[Buddhism in China]], [[Japan]], [[Korea]], and [[Vietnam]]. In [[Japan]] the school is known as [[Tendai]]-shū, and in [[Korea]] it is known as Cheontae. |

| − | The name is derived from the fact that Chih-i, the fourth [[Patriarch]], lived on Mount [[Tiantai]].[[Tiantai]] is sometimes also called "The [[Lotus]] School", after the central role of the [[Lotus Sutra]] in its teachings. | + | The [[name]] is derived from the fact that [[Chih-i]], the fourth [[Patriarch]], lived on Mount [[Tiantai]].[[Tiantai]] is sometimes also called "The [[Lotus]] School", after the {{Wiki|central}} role of the [[Lotus Sutra]] in its teachings. |

| − | During the Tang Dynasty, the [[Tiantai]] school became one of the leading schools of [[Chinese Buddhism]], with numerous large temples supported by emperors and wealthy patrons, with many thousands of [[Monks]] and millions of followers. | + | During the {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}}, the [[Tiantai]] school became one of the leading schools of [[Chinese Buddhism]], with numerous large [[temples]] supported by {{Wiki|emperors}} and wealthy patrons, with many thousands of [[Monks]] and millions of followers. |

| − | History | + | {{Wiki|History}} |

| − | The Tien-Tai school was founded during the Suei dynasty (589-618). Tien-Tai means 'Celestial Terrace' and is the name of a famous monastic mountain (Fig. 1, Kwo-Chin-Temple) where this school's founder, Chih-I (538-597), spent the majority of his life teaching there. | + | The [[Tien-Tai]] school was founded during the Suei dynasty (589-618). [[Tien-Tai]] means '[[Celestial]] Terrace' and is the [[name]] of a famous [[monastic]] mountain (Fig. 1, Kwo-Chin-Temple) where this school's founder, [[Chih-I]] (538-597), spent the majority of his [[life]] [[teaching]] there. |

| − | This school is most famous for its profound interpretation of the Lotus Sutra (the main purpose of the sutra is to establish the one path, or vehicle, for attaining Buddhahood) and Chih-I's system of synthesizing the disparate teachings found in the Chinese Buddhist canon. Because this doctrine is based on the Lotus Sutra, it is also called the Lotus school. | + | This school is most famous for its profound interpretation of the [[Lotus Sutra]] (the main [[purpose]] of the [[sutra]] is to establish the one [[path]], or [[vehicle]], for [[attaining]] [[Buddhahood]]) and Chih-I's system of synthesizing the disparate teachings found in the [[Chinese Buddhist canon]]. Because this [[doctrine]] is based on the [[Lotus Sutra]], it is also called the [[Lotus]] school. |

| − | Nagarjuna is regarded as the first patriarch of this school because his commentary works on Prajnaparamita Sutra (Treatise on the Transcendent Virtue of Great Wisdom. Chinese, Ta-Chih-Tu-Lun) stated "The wisdom which understands the principle of emptiness, the wisdom which understands the phenomenal differences and the Buddha wisdom (the three kinds of wisdom) are actually attained by one thought". This statement was further expanded by the second patriarch, Hui-Wen, and his student Hui-Sze (514-577), the third patriarch who was also Chih-I's teacher, which formed the early structure of the Three-views theory. This theory later became the root theory of Tien-Tai school but the completed philosophic system of the school was not fully established until Chih-I finished the commentary work on the Lotus Sutra. | + | [[Nagarjuna]] is regarded as the first [[patriarch]] of this school because his commentary works on [[Prajnaparamita Sutra]] (Treatise on the [[Transcendent]] [[Virtue]] of [[Great]] [[Wisdom]]. {{Wiki|Chinese}}, Ta-Chih-Tu-Lun) stated "The [[wisdom]] which [[understands]] the {{Wiki|principle}} of [[emptiness]], the [[wisdom]] which [[understands]] the [[phenomenal]] differences and the [[Buddha wisdom]] (the [[three kinds of wisdom]]) are actually attained by one [[thought]]". This statement was further expanded by the second [[patriarch]], Hui-Wen, and his student Hui-Sze (514-577), the third [[patriarch]] who was also Chih-I's [[teacher]], which formed the early structure of the Three-views {{Wiki|theory}}. This {{Wiki|theory}} later became the [[root]] {{Wiki|theory}} of [[Tien-Tai]] school but the completed [[philosophic]] system of the school was not fully established until [[Chih-I]] finished the commentary work on the [[Lotus Sutra]]. |

| − | This school takes as a premise that all phenomena are an expression of the true suchness (absoluteness) and this absoluteness is expressed in three phenomenon truths. One can only be fully enlightened by achieving the complete understanding of the three truths taught by the Buddha. These three phenomenon truths are: | + | This school takes as a premise that all [[phenomena]] are an expression of the [[true suchness]] (absoluteness) and this absoluteness is expressed in three [[phenomenon]] [[truths]]. One can only be [[fully enlightened]] by achieving the complete [[understanding]] of the [[three truths]] taught by the [[Buddha]]. These three [[phenomenon]] [[truths]] are: |

| − | Dependent reality: A phenomenon is produced by various causes, its essence is devoid of any permanent existence. | + | Dependent [[reality]]: A [[phenomenon]] is produced by various [[causes]], its [[essence]] is devoid of any [[permanent]] [[existence]]. |

| − | Phenomenal existence: This existence is temporary, and has its limitation. | + | [[Phenomenal existence]]: This [[existence]] is temporary, and has its limitation. |

| − | Middle: This truth of the middle is equated with true suchness, and it can not be found elsewhere than in phenomena. According to this truth, Dependent reality and Phenomenal existence are one. | + | Middle: This [[truth]] of the middle is equated with [[true suchness]], and it can not be found elsewhere than in [[phenomena]]. According to this [[truth]], Dependent [[reality]] and [[Phenomenal existence]] are one. |

| − | And the only way to obtain the full awareness of the above truths is the Three views (or three insights): | + | And the only way to obtain the full [[awareness]] of the above [[truths]] is the Three [[views]] (or three [[insights]]): |

| − | Emptiness: Phenomena posses no independent reality and they can not exist without other factors, therefore nothing is eternal. | + | [[Emptiness]]: [[Phenomena]] posses no independent [[reality]] and they can not [[exist]] without other factors, therefore [[nothing]] is [[eternal]]. |

| − | Unreality: Although a phenomenon has the apparent existence of phenomena and can be perceived by the senses, because its nature of emptiness, this phenomenon is temporary and unreal. | + | Unreality: Although a [[phenomenon]] has the apparent [[existence]] of [[phenomena]] and can be [[perceived]] by the [[senses]], because its nature of [[emptiness]], this [[phenomenon]] is temporary and unreal. |

| − | Middle Way: Since a phenomenon is blended of emptiness and unreality, it is incorrect to view the truth in any of the above two poles. The proper action is to view a phenomenon and its parts as a whole, all phenomena are merged and contain one another. | + | [[Middle Way]]: Since a [[phenomenon]] is blended of [[emptiness]] and unreality, it is incorrect to [[view]] the [[truth]] in any of the above two poles. The proper [[action]] is to [[view]] a [[phenomenon]] and its parts as a whole, all [[phenomena]] are merged and contain one another. |

| − | The practice of this school consists of meditation based on the methods of Chih Kwan. The notion of Chih Kwan puts equal emphasis on the doctrinal and practical aspects which comprises the noble teachings that the Buddha proclaimed during his life. The Chih-Kuan practice contains: | + | The practice of this school consists of [[meditation]] based on the methods of Chih Kwan. The notion of Chih Kwan puts {{Wiki|equal}} emphasis on the [[doctrinal]] and practical aspects which comprises the [[noble]] teachings that the [[Buddha]] proclaimed during his [[life]]. The Chih-Kuan practice contains: |

| − | Chih (Samatha, Concentration): This is a technique to subdue those mental factors that fetter man to suffering so the further arising of illusions can be prevented. | + | Chih ([[Samatha]], [[Concentration]]): This is a technique to subdue those [[mental factors]] that [[fetter]] man to [[suffering]] so the further [[arising]] of [[illusions]] can be prevented. |

| − | Kuan (Vipasyana, Contemplation): Through understanding of the three Phenomenon truths and Three views, enlightenment may be attained in a single spontaneous thought. "The whole world is contained in a mustard seed," and "Three Thousand Words in One Thought" are the famous Tien-Tai theories about how one thought embodies the universality of all things. | + | Kuan ([[Vipasyana]], [[Contemplation]]): Through [[understanding]] of the three [[Phenomenon]] [[truths]] and Three [[views]], [[enlightenment]] may be attained in a single spontaneous [[thought]]. "The whole [[world]] is contained in a mustard seed," and "Three Thousand Words in One [[Thought]]" are the famous [[Tien-Tai]] theories about how one [[thought]] [[embodies]] the universality of all things. |

| − | The principal works of this school are the " Tien-tai three big books" and " Tien-tai five small books". The Three Big Books are: | + | The principal works of this school are the " [[Tien-tai]] three big [[books]]" and " [[Tien-tai]] five small [[books]]". The Three Big [[Books]] are: |

| − | The Profound Meaning of Lotus Sutra (Chinese, Fa-Hwa-Shuan-Ye): It uses the title of Lotus Sutra as the base to explore the true meaning of the Buddha's teaching. | + | The Profound Meaning of [[Lotus Sutra]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}}, Fa-Hwa-Shuan-Ye): It uses the title of [[Lotus Sutra]] as the base to explore the [[true meaning]] of the [[Buddha's teaching]]. |

| − | The Commentary of Lotus Sutra (Chinese, Fa-Hwa-Wen-Gui): It addresses the commentary of the contents of Lotus Sutra. | + | The Commentary of [[Lotus Sutra]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}}, Fa-Hwa-Wen-Gui): It addresses the commentary of the contents of [[Lotus Sutra]]. |

| − | Maha(Greater)-Samatha-Vipasyana (Chinese, Mou-Her-Chih-Kwan): It describes the right Chih-Kuan techniques to achieve the three virtues of nirvana, namely the true Dharma body (dharmakaya), wisdom of enlightenment, and liberation from suffering. | + | Maha(Greater)-Samatha-Vipasyana ({{Wiki|Chinese}}, Mou-Her-Chih-Kwan): It describes the right Chih-Kuan techniques to achieve the three [[virtues]] of [[nirvana]], namely the true [[Dharma body]] ([[dharmakaya]]), [[wisdom]] of [[enlightenment]], and [[liberation]] from [[suffering]]. |

| − | The Five Small Books are commentaries on five Mahayana sutras. These sutras are: | + | The Five Small [[Books]] are commentaries on five [[Mahayana sutras]]. These [[sutras]] are: |

| − | The Commentary of the Visualization Of Buddha Amitayus Sutra | + | The Commentary of the [[Visualization]] Of [[Buddha Amitayus]] [[Sutra]] |

| − | The Profound Meaning of Golden-light Sutra | + | The Profound Meaning of Golden-light [[Sutra]] |

| − | The Commentary of Golden-light Sutra | + | The Commentary of Golden-light [[Sutra]] |

| − | The Profound Meaning of Kuan-Yin Sutra | + | The Profound Meaning of [[Kuan-Yin]] [[Sutra]] |

| − | The Commentary of Kuan-Yin Sutra | + | The Commentary of [[Kuan-Yin]] [[Sutra]] |

| − | Other important teachings from Chih-I include Six Wondrous Gates of Liberation (Chinese, Liu-Miao-Fa-Men), Smaller-Samatha-Vipasyana (or Beginner's Samatha-Vipasyana), and Gradual Samatha-Vipasyana (or Explanation of the Gradual Dharma Door of the Dhyana Paramita. Chinese, She-Zen-Po-Luo-Mi). | + | Other important teachings from [[Chih-I]] include Six Wondrous Gates of [[Liberation]] ({{Wiki|Chinese}}, Liu-Miao-Fa-Men), Smaller-Samatha-Vipasyana (or Beginner's Samatha-Vipasyana), and Gradual Samatha-Vipasyana (or Explanation of the Gradual [[Dharma Door]] of the [[Dhyana]] [[Paramita]]. {{Wiki|Chinese}}, She-Zen-Po-Luo-Mi). |

| − | The Tien-Tai school is generally considered a syncretistic school, because it synthesizes different viewpoints of other Buddhist schools from India. It represents an attempt to systematize the teachings of Buddha, to resolve different understanding of teachings arising within Buddhism of different doctrines, and to provide ways of solving metaphysical problems. In order to accomplish these objectives, Chih-I classified the teaching of Buddha into "five periods and eight teachings." It provides a place for the most widely different sutras and regards the Hinayana as well as the Mahayana as an authentic doctrinal expression of the Buddha. | + | The [[Tien-Tai]] school is generally considered a syncretistic school, because it synthesizes different viewpoints of other [[Buddhist]] schools from [[India]]. It represents an attempt to systematize the teachings of [[Buddha]], to resolve different [[understanding]] of teachings [[arising]] within [[Buddhism]] of different [[doctrines]], and to provide ways of solving [[metaphysical]] problems. In [[order]] to accomplish these objectives, [[Chih-I]] classified the [[teaching]] of [[Buddha]] into "[[five periods]] and [[eight teachings]]." It provides a place for the most widely different [[sutras]] and regards the [[Hinayana]] as well as the [[Mahayana]] as an authentic [[doctrinal]] expression of the [[Buddha]]. |

| − | The division of five periods is based on chronological criteria: | + | The division of [[five periods]] is based on {{Wiki|chronological}} criteria: |

The period of the Avatamsaka-sutras | The period of the Avatamsaka-sutras | ||

| − | These sutras were taught by the Buddha immediately after attaining his enlightenment. It revealed the greatness of Buddhism that universe is the expression of the true suchness (absoluteness). The target audiences were the Budhisattvas though the teachings were too profound for most of the Buddha's general disciples to grasp. This phase lasted for twenty-one days. | + | These [[sutras]] were taught by the [[Buddha]] immediately after [[attaining]] his [[enlightenment]]. It revealed the greatness of [[Buddhism]] that [[universe]] is the expression of the [[true suchness]] (absoluteness). The target audiences were the Budhisattvas though the teachings were too profound for most of the [[Buddha's]] {{Wiki|general}} [[disciples]] to [[grasp]]. This phase lasted for twenty-one days. |

The period of the Agamas-sutra | The period of the Agamas-sutra | ||

| − | Because the Buddha's disciples did not understand the principal idea of the teaching during the first period, he then expounded the four noble truths, the eight-fold path, and the teaching of dependent-arising (pratitya-samutpada) as a means to develop the understanding of the truth. This teaching was Agamas and it lasted for twelve years. | + | Because the [[Buddha's]] [[disciples]] did not understand the principal [[idea]] of the [[teaching]] during the first period, he then expounded the [[four noble truths]], the [[eight-fold path]], and the [[teaching]] of [[dependent-arising]] ([[pratitya-samutpada]]) as a means to develop the [[understanding]] of the [[truth]]. This [[teaching]] was [[Agamas]] and it lasted for twelve years. |

The period of the Vaipulya-sutras | The period of the Vaipulya-sutras | ||

| − | In this teaching the Buddha taught the introduction of the Mahayana, he stated the superiority of a Budhisattva over an Arhat, and the unity of Buddha and sentient beings, of absoluteness and relative. This phase lasted for eight years, | + | In this [[teaching]] the [[Buddha]] taught the introduction of the [[Mahayana]], he stated the superiority of a Budhisattva over an [[Arhat]], and the unity of [[Buddha]] and [[sentient beings]], of absoluteness and [[relative]]. This phase lasted for eight years, |

| − | The period of the Prajnaparamita-sutra | + | The period of the [[Prajnaparamita-sutra]] |

| − | The Buddha taught his disciples the meaning of emptiness in this period. Three of the central teachings on emptiness are the great, middle-length and shorter Prajnaparamita-sutra (Perfection of Wisdom Sutras). In all of these sutras, a complete explanation of both aspects of the path to Buddhahood, i.e. wisdom and method, was given. The fourth period lasted for twenty-two years. | + | The [[Buddha]] taught his [[disciples]] the [[meaning]] of [[emptiness]] in this period. Three of the {{Wiki|central}} teachings on [[emptiness]] are the great, middle-length and shorter [[Prajnaparamita-sutra]] ([[Perfection of Wisdom]] [[Sutras]]). In all of these [[sutras]], a complete explanation of both aspects of the [[path]] to [[Buddhahood]], i.e. [[wisdom]] and method, was given. The fourth period lasted for twenty-two years. |

| − | The period of the Lotus Sutra and Mahaparinirvana-sutra | + | The period of the [[Lotus Sutra]] and Mahaparinirvana-sutra |

| − | In the fifth and last period, which corresponds to the last eight years of Buddha's life, he emphasized the absolute identity of all opposites. The teachings during the last period expounded the ultimate and complete truth. It essentially concluded the previous four periods of teachings and stated that the three vehicles (triyana) of the Shravakas, Pratyeka-buddhas, and Bodhisattvas have only provisional validity and all of them will eventually merge into a single vehicle (ekayana) toward the Great Nirvana. | + | In the fifth and last period, which corresponds to the last eight years of [[Buddha's]] [[life]], he emphasized the [[absolute]] [[identity]] of all opposites. The teachings during the last period expounded the [[ultimate]] and complete [[truth]]. It [[essentially]] concluded the previous four periods of teachings and stated that the [[three vehicles]] (triyana) of the [[Shravakas]], [[Pratyeka-buddhas]], and [[Bodhisattvas]] have only provisional validity and all of them will eventually merge into a single [[vehicle]] ([[ekayana]]) toward the [[Great]] [[Nirvana]]. |

| − | This represents a chronological division of the teaching. The school also holds the view that the Buddha taught the teachings of the five periods simultaneously. The reason why these teachings were viewed differently was because of the disciples' understanding and the methods that the Buddha was using. This leads to a systematization of the Buddha's teaching into eight doctrines: four of which are to be considered from the point of view of method and four from the point of view of content. | + | This represents a {{Wiki|chronological}} division of the [[teaching]]. The school also holds the [[view]] that the [[Buddha]] taught the teachings of the [[five periods]] simultaneously. The [[reason]] why these teachings were viewed differently was [[because of]] the [[disciples]]' [[understanding]] and the methods that the [[Buddha]] was using. This leads to a systematization of the [[Buddha's teaching]] into eight [[doctrines]]: four of which are to be considered from the point of [[view]] of method and four from the point of [[view]] of content. |

| − | These eight teachings, even shown as different paths, are all capable of leading the practitioners to the final enlightenment. And the techniques of achieving nirvana are considered universal because it advocates the notion of universal liberation, which is possible because all beings and things possess Buddha-nature and because they all make use of available means for the realization of enlightenment. | + | These [[eight teachings]], even shown as different [[paths]], are all capable of leading the practitioners to the final [[enlightenment]]. And the techniques of achieving [[nirvana]] are considered [[universal]] because it advocates the notion of [[universal]] [[liberation]], which is possible because all [[beings]] and things possess [[Buddha-nature]] and because they all make use of available means for the [[realization]] of [[enlightenment]]. |

| − | The first group of the teachings is considered from the point of view of method, which includes: | + | The first group of the teachings is considered from the point of [[view]] of method, which includes: |

| − | The Sudden method: Which is to be used with the most talented students who understand the truth directly. This is the method of the Avatamsaka sutra. | + | The Sudden method: Which is to be used with the most talented students who understand the [[truth]] directly. This is the method of the [[Avatamsaka sutra]]. |

| − | The Gradual method: Which progresses from elementary to more complex doctrines and includes the Agama, Vaipulya-sutra, and Prajnaparamita-sutra periods. The Lotus Sutra is excluded. | + | The Gradual method: Which progresses from elementary to more complex [[doctrines]] and includes the [[Agama]], [[Vaipulya-sutra]], and [[Prajnaparamita-sutra]] periods. The [[Lotus Sutra]] is excluded. |

| − | The Secret method: Which is to be used only when addressing individuals. The Buddha's teaching, in this case, was understood only by the selected disciples. Other disciples could have been present, but owing to the supernatural power of the Buddha, they would not have been aware of what he said to them individually. | + | The Secret method: Which is to be used only when addressing {{Wiki|individuals}}. The [[Buddha's teaching]], in this case, was understood only by the selected [[disciples]]. Other [[disciples]] could have been present, but owing to the [[supernatural power]] of the [[Buddha]], they would not have been aware of what he said to them individually. |

| − | The Indeterminate method: In which, the individual disciples were attending the same session, they heard and understood the Buddha's words in different ways. | + | The {{Wiki|Indeterminate}} method: In which, the {{Wiki|individual}} [[disciples]] were attending the same session, they [[heard]] and understood the [[Buddha's]] words in different ways. |

| − | The last two methods were used by the Buddha when he wanted to instruct disciples of different capacities at the same time. | + | The last two methods were used by the [[Buddha]] when he wanted to instruct [[disciples]] of different capacities at the same [[time]]. |

| − | The second group of the teachings is considered from the point of view of content, which includes: | + | The second group of the teachings is considered from the point of [[view]] of content, which includes: |

| − | The Hinayana teachings: It is meant for Shravakas and Pratyeka-buddhas. | + | The [[Hinayana]] teachings: It is meant for [[Shravakas]] and [[Pratyeka-buddhas]]. |

| − | The Common teaching (common to the Hinayana and the Mahayana): It is meant for the Shravakas, Pratyeka-buddhas, and lower-level Bodhisattvas. | + | The Common [[teaching]] (common to the [[Hinayana]] and the [[Mahayana]]): It is meant for the [[Shravakas]], [[Pratyeka-buddhas]], and lower-level [[Bodhisattvas]]. |

| − | The Special teaching: It is dedicated for the Bodhisattvas. | + | The Special [[teaching]]: It is dedicated for the [[Bodhisattvas]]. |

| − | The Complete (Round) teaching: The teaching of the Middle Way. Any teaching given by the Buddha should be considered as the ultimate teaching regardless of the methods. | + | The Complete (Round) [[teaching]]: The [[teaching]] of the [[Middle Way]]. Any [[teaching]] given by the [[Buddha]] should be considered as the [[ultimate]] [[teaching]] regardless of the methods. |

| − | The period of the Avatamsaka-sutra included Special and Round teachings. The Agamas-sutra was the only teaching of the Hinayana. The Vaipulya-sutras phase covered all four teachings. The Prajnaparamita-sutra contained Round teaching but also covered Common and Special teachings. Only the Lotus-sutra could be regarded as really the Round teaching. | + | The period of the [[Avatamsaka-sutra]] included Special and Round teachings. The Agamas-sutra was the only [[teaching]] of the [[Hinayana]]. The Vaipulya-sutras phase covered all four teachings. The [[Prajnaparamita-sutra]] contained Round [[teaching]] but also covered Common and Special teachings. Only the Lotus-sutra could be regarded as really the Round [[teaching]]. |

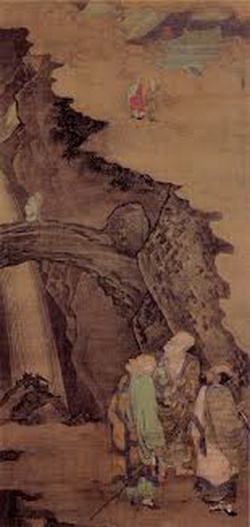

The [[Bodhisattva]] [[Avalokiteśvara]], an important figure from the [[Lotus]] [[Sūtra]]. | The [[Bodhisattva]] [[Avalokiteśvara]], an important figure from the [[Lotus]] [[Sūtra]]. | ||

| − | Most scholars regard the [[Tiantai]] as one of the first truly Chinese schools of Buddhist [[Thought]]. The [[Schools of Buddhism]] that had existed in China prior to the emergence of the [[Tiantai]] are generally believed to represent direct transplantations from [[India]], with little modification to their basic doctrines and methods. The creation of the [[Tiantai]] school signified the maturation and integration of [[Buddhism]] in the Chinese context. No longer content to simply translate texts received from Indian sources, Chinese Buddhists began to apply new analyses to old texts, and even to produce new scriptures and commentaries that would attain significant status within the East Asian sphere. | + | Most [[scholars]] regard the [[Tiantai]] as one of the first truly {{Wiki|Chinese}} schools of [[Buddhist]] [[Thought]]. The [[Schools of Buddhism]] that had existed in [[China]] prior to the [[emergence]] of the [[Tiantai]] are generally believed to represent direct transplantations from [[India]], with little modification to their basic [[doctrines]] and methods. The creation of the [[Tiantai]] school signified the maturation and {{Wiki|integration}} of [[Buddhism]] in the {{Wiki|Chinese}} context. No longer content to simply translate texts received from [[Indian]] sources, {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhists]] began to apply new analyses to old texts, and even to produce new [[scriptures]] and commentaries that would attain significant {{Wiki|status}} within the {{Wiki|East Asian}} [[sphere]]. |

| − | The [[Tiantai]] school became doctrinally broad, able to absorb and give rise to other movements within [[Buddhism]]. The tradition emphasized both scriptural study and [[Meditative]] practice, and taught the rapid [[Attainment of Buddhahood]] through observing the [[Mind]]. | + | The [[Tiantai]] school became doctrinally broad, able to absorb and give rise to other movements within [[Buddhism]]. The [[tradition]] emphasized both scriptural study and [[Meditative]] practice, and taught the rapid [[Attainment of Buddhahood]] through observing the [[Mind]]. |

[[File:Iantai2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Iantai2.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The school is largely based on the teachings of [[Zhiyi]], Zhanran, and Zhili, who lived between the 6th and 11th centuries in China. These teachers took an approach called "classification of teaching" in an attempt to harmonize the numerous and often contradictory [[Buddhist texts]] that had come into China. This was achieved through a particular interpretation of the [[Lotus]] [[Sūtra]]. | + | The school is largely based on the teachings of [[Zhiyi]], [[Zhanran]], and Zhili, who lived between the 6th and 11th centuries in [[China]]. These [[teachers]] took an approach called "{{Wiki|classification}} of [[teaching]]" in an attempt to harmonize the numerous and often contradictory [[Buddhist texts]] that had come into [[China]]. This was achieved through a particular interpretation of the [[Lotus]] [[Sūtra]]. |

| − | Patriarchs | + | [[Patriarchs]] |

| − | Due to the use of [[Nāgārjuna]]'s philosophy of the [[Middle Way]], [[Nagarjuna]] is traditionally taken to be the first [[Patriarch]] of the [[Tiantai]] school. | + | Due to the use of [[Nāgārjuna]]'s [[philosophy]] of the [[Middle Way]], [[Nagarjuna]] is [[traditionally]] taken to be the first [[Patriarch]] of the [[Tiantai]] school. |

| − | The sixth century [[Dhyāna]] master Huiwen (慧文) is traditionally considered to be the second [[Patriarch]] of the [[Tiantai]] school. Huiwen studied the works of [[Nāgārjuna]], and is said to have [[Awakened]] to the profound meaning of [[Nāgārjuna]]'s words: "All conditioned [[Phenomena]] I speak of as empty, and are but false names which also indicate the mean." | + | The sixth century [[Dhyāna]] [[master]] Huiwen (慧文) is [[traditionally]] considered to be the second [[Patriarch]] of the [[Tiantai]] school. Huiwen studied the works of [[Nāgārjuna]], and is said to have [[Awakened]] to the profound [[meaning]] of [[Nāgārjuna]]'s words: "All [[conditioned]] [[Phenomena]] I speak of as [[empty]], and are but false names which also indicate the mean." |

| − | Huiwen later transmitted his teachings to the [[Dhyāna]] master Huisi (Ch. 慧思, 515-577 CE), who is traditionally figured as the third [[Patriarch]]. During [[Meditation]], he is said to have realized the [[Lotus]] [[Samādhi]], indicating [[Enlightenment]] and [[Buddhahood]]. He authored the text [[Mahāyāna]]-śamatha-vipaśyanā. | + | Huiwen later transmitted his teachings to the [[Dhyāna]] [[master]] [[Huisi]] (Ch. 慧思, 515-577 CE), who is [[traditionally]] figured as the third [[Patriarch]]. During [[Meditation]], he is said to have [[realized]] the [[Lotus]] [[Samādhi]], indicating [[Enlightenment]] and [[Buddhahood]]. He authored the text [[Mahāyāna]]-śamatha-vipaśyanā. |

| − | [[Venerable]] Huisi then transmitted his teachings to Śramaṇa [[Zhiyi]] (Ch. 智顗, 538-597 CE), who is traditionally figured as the fourth [[Patriarch]] of [[Tiantai]], who is said to have practiced the [[Lotus]] [[Samādhi]] and to have become [[Enlightened]] quickly. He authored many treatises such as explanations of the [[Buddhist texts]], and especially systematic manuals of various lengths which explain and enumerate methods of Buddhist practice and [[Meditation]]. The above lineage was proposed by Buddhists of later times and do not reflect the popularity of the [[Monks]] at that time. | + | [[Venerable]] [[Huisi]] then transmitted his teachings to [[Śramaṇa]] [[Zhiyi]] (Ch. 智顗, 538-597 CE), who is [[traditionally]] figured as the fourth [[Patriarch]] of [[Tiantai]], who is said to have practiced the [[Lotus]] [[Samādhi]] and to have become [[Enlightened]] quickly. He authored many treatises such as explanations of the [[Buddhist texts]], and especially systematic manuals of various lengths which explain and enumerate methods of [[Buddhist practice]] and [[Meditation]]. The above [[lineage]] was proposed by [[Buddhists]] of later times and do not reflect the popularity of the [[Monks]] at that [[time]]. |

[[Zhiyi]] | [[Zhiyi]] | ||

| − | Most scholars consider [[Zhiyi]] to have been the major founder of the [[Tiantai]] school, since he did the most to systematize and popularize the doctrines and methods associated with it. At a later date, the school's sixth [[Patriarch]], Zhanran, would compose clarifying commentaries on [[Zhiyi]]'s writings. | + | Most [[scholars]] consider [[Zhiyi]] to have been the major founder of the [[Tiantai]] school, since he did the most to systematize and popularize the [[doctrines]] and methods associated with it. At a later date, the school's sixth [[Patriarch]], [[Zhanran]], would compose clarifying commentaries on [[Zhiyi]]'s writings. |

[[File:Tiantai-s.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Tiantai-s.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Zhiyi]] analyzed and organized all the Āgamas and [[Mahayana]] [[Sutras]] into a system of [[Five periods]] and eight types of teachings. For example, many elementary doctrines and bridging concepts had been taught early in The [[Buddha]]'s advent when the vast majority of the people during his time were not yet ready to grasp the 'ultimate [[Truth]]'. These teachings (the Āgamas) were an upaya, or skillful means, were simply an example of The [[Buddha]] employing his boundless [[Wisdom]] to lead those people towards the [[Truth]]. Subsequent teachings delivered to more advanced followers thus represent a more complete and accurate picture of The [[Buddha]]'s teachings, and did away with some of the philosophical 'crutches' introduced earlier. [[Zhiyi]]'s classification culminated with the [[Lotus Sutra]], which he held to be the supreme synthesis of Buddhist [[Doctrine]]. The difference on [[Zhiyi]]'s explanation to the [[Golden Light Sutra]] caused a debate in Song Dynasty. | + | [[Zhiyi]] analyzed and organized all the [[Āgamas]] and [[Mahayana]] [[Sutras]] into a system of [[Five periods]] and eight types of teachings. For example, many elementary [[doctrines]] and bridging concepts had been taught early in The [[Buddha]]'s advent when the vast majority of the [[people]] during his [[time]] were not yet ready to [[grasp]] the '[[ultimate]] [[Truth]]'. These teachings (the [[Āgamas]]) were an [[upaya]], or [[skillful means]], were simply an example of The [[Buddha]] employing his [[boundless]] [[Wisdom]] to lead those [[people]] towards the [[Truth]]. Subsequent teachings delivered to more advanced followers thus represent a more complete and accurate picture of The [[Buddha]]'s teachings, and did away with some of the [[philosophical]] 'crutches' introduced earlier. [[Zhiyi]]'s {{Wiki|classification}} culminated with the [[Lotus Sutra]], which he held to be the [[supreme]] synthesis of [[Buddhist]] [[Doctrine]]. The [[difference]] on [[Zhiyi]]'s explanation to the [[Golden Light Sutra]] [[caused]] a [[debate]] in {{Wiki|Song Dynasty}}. |

Texts | Texts | ||

| − | The [[Tiantai]] school takes the [[Lotus]] [[Sūtra]] (Saddharmapuṇḍarīka [[Sūtra]]) as the main basis, the Mahā[[Prajñā]]pāramitā Śāstra of [[Nāgārjuna]] as the guide, the [[Nirvāṇa]] [[Sūtra]] as the support, and the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā [[Prajñā]]pāramitā [[Sūtra]] for methods of contemplation. | + | The [[Tiantai]] school takes the [[Lotus]] [[Sūtra]] (Saddharmapuṇḍarīka [[Sūtra]]) as the main basis, the Mahā[[Prajñā]][[pāramitā]] [[Śāstra]] of [[Nāgārjuna]] as the guide, the [[Nirvāṇa]] [[Sūtra]] as the support, and the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā [[Prajñā]][[pāramitā]] [[Sūtra]] for methods of [[contemplation]]. |

| − | In addition to its doctrinal basis in Indian [[Buddhist texts]], the [[Tiantai]] school also emphasizes use of its own [[Meditation]] texts which emphasize the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Of the [[Tiantai]] [[Meditation]] treatises, [[Zhiyi]]'s Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā (小止観), Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā (摩訶止観), and Six Subtle [[Dharma]] Gates (六妙法門) are the most widely read in China.[5] Rujun Wu identifies the work Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā of [[Zhiyi]] as the seminal [[Meditation]] text of the [[Tiantai]] school. | + | In addition to its [[doctrinal]] basis in [[Indian]] [[Buddhist texts]], the [[Tiantai]] school also emphasizes use of its own [[Meditation]] texts which emphasize the {{Wiki|principles}} of [[śamatha]] and [[vipaśyanā]]. Of the [[Tiantai]] [[Meditation]] treatises, [[Zhiyi]]'s Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā (小止観), Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā (摩訶止観), and Six {{Wiki|Subtle}} [[Dharma]] Gates (六妙法門) are the most widely read in [[China]].[5] Rujun Wu identifies the work Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā of [[Zhiyi]] as the seminal [[Meditation]] text of the [[Tiantai]] school. |

| − | Classification of teachings | + | {{Wiki|Classification}} of teachings |

| − | [[Tiantai]] classified The [[Buddha]]'s teachings in [[Five periods]] and [[Eight teachings]]. This classification is usually attributed to Chih-i, but is probably a later development. The classification of teachings was also done by other schools, such as the Fivefold Classification of the [[Huayan school]]. | + | [[Tiantai]] classified The [[Buddha]]'s teachings in [[Five periods]] and [[Eight teachings]]. This {{Wiki|classification}} is usually attributed to [[Chih-i]], but is probably a later development. The {{Wiki|classification}} of teachings was also done by other schools, such as the Fivefold {{Wiki|Classification}} of the [[Huayan school]]. |

[[Five periods]] | [[Five periods]] | ||

| − | The [[Five periods]] are [[Five periods]] in the [[life of the Buddha]] in which he delivered different teachings, aimed at different audiences with a different level of understanding: | + | The [[Five periods]] are [[Five periods]] in the [[life of the Buddha]] in which he delivered different teachings, aimed at different audiences with a different level of [[understanding]]: |

[[File:Tiantai.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Tiantai.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The Period of Avatamsaka. During twenty-one days after his [[Enlightenment]], The [[Buddha]] delivered the Avatamsaka [[Sutra]]. | + | The Period of [[Avatamsaka]]. During twenty-one days after his [[Enlightenment]], The [[Buddha]] delivered the [[Avatamsaka]] [[Sutra]]. |

| − | The Period of Agamas. During twelve years, The [[Buddha]] preached the Agamas for the Nihayana, including The [[Four Noble Truths]] and [[Dependent origination]]. | + | The Period of [[Agamas]]. During twelve years, The [[Buddha]] {{Wiki|preached}} the [[Agamas]] for the Nihayana, including The [[Four Noble Truths]] and [[Dependent origination]]. |

| − | The Period of Vaipulya. During eight years, The [[Buddha]] delivered the [[Mahayana]] teachings, such as the [[Vimalakirti Sutra]], the Śrīmālādevī [[Sūtra]], the Suvarnaprabhasa [[Sutra]] and other [[Mahayana]] [[Sutras]]. | + | The Period of [[Vaipulya]]. During eight years, The [[Buddha]] delivered the [[Mahayana]] teachings, such as the [[Vimalakirti Sutra]], the Śrīmālādevī [[Sūtra]], the Suvarnaprabhasa [[Sutra]] and other [[Mahayana]] [[Sutras]]. |

The Period of [[Prajna]]. During twenty-two years, The [[Buddha]] explained [[Emptiness]] in the [[Prajnaparamita]]-[[Sutras]]. | The Period of [[Prajna]]. During twenty-two years, The [[Buddha]] explained [[Emptiness]] in the [[Prajnaparamita]]-[[Sutras]]. | ||

| − | The Period of [[Dharma]]-pundarik and [[Nirvana]]. In the last eight years, The [[Buddha]] preached the [[Doctrine]] of the One [[Buddha Vehicle]], and delivered the [[Lotus Sutra]] and the [[Nirvana]] [[Sutra]] just before his [[Death]]. | + | The Period of [[Dharma]]-pundarik and [[Nirvana]]. In the last eight years, The [[Buddha]] {{Wiki|preached}} the [[Doctrine]] of the One [[Buddha Vehicle]], and delivered the [[Lotus Sutra]] and the [[Nirvana]] [[Sutra]] just before his [[Death]]. |

[[Eight teachings]] | [[Eight teachings]] | ||

| − | The [[Eight teachings]] consist of the Four Doctrines, and the Fourfold Methods. | + | The [[Eight teachings]] consist of the Four [[Doctrines]], and the Fourfold Methods. |

| − | Four Doctrines | + | Four [[Doctrines]] |

| − | [[Tripitaka]] Teaching: the [[Sutra]], [[Vinaya]] and [[Abhidhamma]], in which the basic teachings are explained | + | [[Tripitaka]] [[Teaching]]: the [[Sutra]], [[Vinaya]] and [[Abhidhamma]], in which the basic teachings are explained |

| − | Shared Teaching: the teaching of [[Emptiness]] | + | Shared [[Teaching]]: the [[teaching]] of [[Emptiness]] |

| − | Distinctive Teaching: aimed at the [[Bodhisattva]] | + | {{Wiki|Distinctive}} [[Teaching]]: aimed at the [[Bodhisattva]] |

| − | Perfect Teaching - the Chinese teachings of the [[Lotus Sutra]] and the Avatamsaka [[Sutra]] | + | Perfect [[Teaching]] - the {{Wiki|Chinese}} teachings of the [[Lotus Sutra]] and the [[Avatamsaka]] [[Sutra]] |

Fourfold Methods | Fourfold Methods | ||

| − | Gradual Teaching, for those with medium or inferior abilities | + | Gradual [[Teaching]], for those with {{Wiki|medium}} or {{Wiki|inferior}} {{Wiki|abilities}} |

| − | Sudden Teaching, the Distinctive Teachings and the Complete Teaching for those with superior abilities | + | Sudden [[Teaching]], the {{Wiki|Distinctive}} Teachings and the Complete [[Teaching]] for those with {{Wiki|superior}} {{Wiki|abilities}} |

| − | Secret Teaching, teachings which are transmitted without the recipient being aware of it | + | Secret [[Teaching]], teachings which are transmitted without the recipient {{Wiki|being}} aware of it |

| − | Variable Teaching, no fixed teaching, but various teachings for various persons and circumstances | + | Variable [[Teaching]], no fixed [[teaching]], but various teachings for various persons and circumstances |

[[File:Tiantai8_o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Tiantai8_o.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Teachings | Teachings | ||

| − | David Chappell lists the most important teachings as the doctrines of: | + | David Chappell lists the most important teachings as the [[doctrines]] of: |

The Threefold [[Truth]], | The Threefold [[Truth]], | ||

| − | The Threefold Contemplation, | + | The Threefold [[Contemplation]], |

The Fourfold Teachings, | The Fourfold Teachings, | ||

| − | The Subtle [[Dharma]], | + | The {{Wiki|Subtle}} [[Dharma]], |

| − | The Nonconceivable Discernment. | + | The Nonconceivable [[Discernment]]. |

| − | Nan Huaijin, a 20th-century [[Chán]]-teacher, summarizes the main teaching of the [[Tiantai]] school as the following: | + | [[Nan Huaijin]], a 20th-century [[Chán]]-[[teacher]], summarizes the main [[teaching]] of the [[Tiantai]] school as the following: |

| − | The One Vehicle (Skt. Ekayāna), | + | The One [[Vehicle]] (Skt. Ekayāna), |

| − | The vehicle of attaining [[Buddhahood]], as the main principle; | + | The [[vehicle]] of [[attaining]] [[Buddhahood]], as the main {{Wiki|principle}}; |

| − | The three forms of śamatha-vipaśyanā correlated with the [[Meditative]] perspectives of [[Emptiness]], | + | The three [[forms]] of śamatha-vipaśyanā correlated with the [[Meditative]] perspectives of [[Emptiness]], |

| − | The mean, as the method of cultivating realization. | + | The mean, as the method of cultivating [[realization]]. |

The Threefold [[Truth]] | The Threefold [[Truth]] | ||

| − | The [[Tiantai]] school took up the principle of The Threefold [[Truth]], derived from [[Nāgārjuna]]: | + | The [[Tiantai]] school took up the {{Wiki|principle}} of The Threefold [[Truth]], derived from [[Nāgārjuna]]: |

[[File:Tiantai0045.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Tiantai0045.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Phenomena]] are empty of self-nature, | + | [[Phenomena]] are [[empty]] of [[self-nature]], |

| − | [[Phenomena]] exist provisionally from a worldly perspective, | + | [[Phenomena]] [[exist]] provisionally from a [[worldly]] {{Wiki|perspective}}, |

| − | [[Phenomena]] are both empty of existence and exist provisionally at once. | + | [[Phenomena]] are both [[empty]] of [[existence]] and [[exist]] provisionally at once. |

| − | The transient [[World]] of [[Phenomena]] is thus seen as one with the unchanging, undifferentiated substratum of existence. This [[Doctrine]] of interpenetration is reflected in the [[Tiantai]] teaching of three thousand realms in a single moment of [[Thought]]. | + | The transient [[World]] of [[Phenomena]] is thus seen as one with the [[unchanging]], undifferentiated [[substratum]] of [[existence]]. This [[Doctrine]] of interpenetration is reflected in the [[Tiantai]] [[teaching]] of three thousand [[realms]] in a [[single moment]] of [[Thought]]. |

The Threefold [[Truth]] has its basis in [[Nāgārjuna]]: | The Threefold [[Truth]] has its basis in [[Nāgārjuna]]: | ||

| − | All things arise through causes and conditions. | + | All things arise through [[causes]] and [[conditions]]. |

That I declare as [[Emptiness]]. | That I declare as [[Emptiness]]. | ||

It is also a provisional designation. | It is also a provisional designation. | ||

| − | It is also the meaning of the Middle [[Path]]. | + | It is also the [[meaning]] of the Middle [[Path]]. |

Three Contemplations | Three Contemplations | ||

| − | While the Three Truths are essentially one, they may be recognized separately as one undertakes the Three Contemplations: | + | While the [[Three Truths]] are [[essentially]] one, they may be [[recognized]] separately as one undertakes the Three Contemplations: |

| − | The first contemplation involves moving from the [[World]] of provisionality to the [[World]] of [[Emptiness]], or [[Shunyata]]. | + | The first [[contemplation]] involves moving from the [[World]] of provisionality to the [[World]] of [[Emptiness]], or [[Shunyata]]. |

| − | The second contemplation is moving back from the [[World]] of [[Emptiness]] to the [[World]] of provisionality with an acceptance thereof. | + | The second [[contemplation]] is moving back from the [[World]] of [[Emptiness]] to the [[World]] of provisionality with an acceptance thereof. |

| − | The third contemplation involves balancing the previous two by following the Middle [[Path]]. | + | The third [[contemplation]] involves balancing the previous two by following the Middle [[Path]]. |

The Fourfold Teachings | The Fourfold Teachings | ||

| Line 214: | Line 214: | ||

[[Meditation]]-practice | [[Meditation]]-practice | ||

| − | According to Charles Luk, in China it has been traditionally held that the [[Meditation]] methods of the [[Tiantai]] are the most systematic and comprehensive of all. [[Tiantai]] emphasizes śamatha and vipaśyanā [[Meditation]]. | + | According to Charles Luk, in [[China]] it has been [[traditionally]] held that the [[Meditation]] methods of the [[Tiantai]] are the most systematic and comprehensive of all. [[Tiantai]] emphasizes [[śamatha]] and [[vipaśyanā]] [[Meditation]]. |

| − | Regarding the functions of śamatha and vipaśyanā in [[Meditation]], [[Zhiyi]] writes in his work Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā: | + | Regarding the functions of [[śamatha]] and [[vipaśyanā]] in [[Meditation]], [[Zhiyi]] writes in his work Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā: |

| − | The attainment of [[Nirvāṇa]] is realizable by many methods whose essentials do not go beyond the practice of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Śamatha is the first step to untie all bonds and vipaśyanā is essential to root out [[Delusion]]. Śamatha provides nourishment for the preservation of the knowing [[Mind]], and vipaśyanā is the skillful [[Art]] of promoting [[Spiritual]] understanding. Śamatha is the unsurpassed cause of [[Samādhi]], while vipaśyanā begets [[Wisdom]]. | + | The [[attainment]] of [[Nirvāṇa]] is realizable by many methods whose [[essentials]] do not go [[beyond]] the practice of [[śamatha]] and [[vipaśyanā]]. [[Śamatha]] is the first step to untie all bonds and [[vipaśyanā]] is [[essential]] to [[root]] out [[Delusion]]. [[Śamatha]] provides nourishment for the preservation of the [[knowing]] [[Mind]], and [[vipaśyanā]] is the [[skillful]] [[Art]] of promoting [[Spiritual]] [[understanding]]. [[Śamatha]] is the [[unsurpassed]] [[cause]] of [[Samādhi]], while [[vipaśyanā]] begets [[Wisdom]]. |

| − | The [[Tiantai]] school also places a great emphasis on [[Mindfulness]] of Breathing (Skt. ānāpānasmṛti) in accordance with the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. [[Zhiyi]] classifies breathing into four main categories: | + | The [[Tiantai]] school also places a great emphasis on [[Mindfulness]] of {{Wiki|Breathing}} (Skt. ānāpānasmṛti) in accordance with the {{Wiki|principles}} of [[śamatha]] and [[vipaśyanā]]. [[Zhiyi]] classifies {{Wiki|breathing}} into four main categories: |

Panting (喘), | Panting (喘), | ||

| − | Unhurried breathing (風), | + | Unhurried {{Wiki|breathing}} (風), |

| − | Deep and quiet breathing (氣), | + | Deep and quiet {{Wiki|breathing}} (氣), |

Stillness or rest (息). | Stillness or rest (息). | ||

| − | [[Zhiyi]] holds that the first three kinds of breathing are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the breathing should reach stillness and rest. | + | [[Zhiyi]] holds that the first three kinds of {{Wiki|breathing}} are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the {{Wiki|breathing}} should reach stillness and rest. |

| − | Influence | + | [[Influence]] |

| − | David Chappell writes that although the [[Tiantai]] school, "has the reputation of being...the most comprehensive and diversified school of [[Chinese Buddhism]], it is almost unknown in the West" despite having a "religious framework that seemed suited to adapt to other cultures, to evolve new practices, and to universalize [[Buddhism]]". He attributes this failure of expansion to the school having "narrowed its practice to a small number of [[Rituals]]" and because it has "neglected the [[Intellectual]] breadth and subtlety of its founder". | + | David Chappell writes that although the [[Tiantai]] school, "has the reputation of being...the most comprehensive and diversified school of [[Chinese Buddhism]], it is almost unknown in the {{Wiki|West}}" despite having a "[[religious]] framework that seemed suited to adapt to other cultures, to evolve new practices, and to universalize [[Buddhism]]". He attributes this failure of expansion to the school having "narrowed its practice to a small number of [[Rituals]]" and because it has "neglected the [[Intellectual]] breadth and subtlety of its founder". |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

Revision as of 13:22, 17 September 2013

Tiantai (Chinese and Japanese: 天台宗; pinyin: tiāntāi zōng; ) is an important school of Buddhism in China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam. In Japan the school is known as Tendai-shū, and in Korea it is known as Cheontae.

The name is derived from the fact that Chih-i, the fourth Patriarch, lived on Mount Tiantai.Tiantai is sometimes also called "The Lotus School", after the central role of the Lotus Sutra in its teachings.

During the Tang Dynasty, the Tiantai school became one of the leading schools of Chinese Buddhism, with numerous large temples supported by emperors and wealthy patrons, with many thousands of Monks and millions of followers.

History

The Tien-Tai school was founded during the Suei dynasty (589-618). Tien-Tai means 'Celestial Terrace' and is the name of a famous monastic mountain (Fig. 1, Kwo-Chin-Temple) where this school's founder, Chih-I (538-597), spent the majority of his life teaching there.

This school is most famous for its profound interpretation of the Lotus Sutra (the main purpose of the sutra is to establish the one path, or vehicle, for attaining Buddhahood) and Chih-I's system of synthesizing the disparate teachings found in the Chinese Buddhist canon. Because this doctrine is based on the Lotus Sutra, it is also called the Lotus school.

Nagarjuna is regarded as the first patriarch of this school because his commentary works on Prajnaparamita Sutra (Treatise on the Transcendent Virtue of Great Wisdom. Chinese, Ta-Chih-Tu-Lun) stated "The wisdom which understands the principle of emptiness, the wisdom which understands the phenomenal differences and the Buddha wisdom (the three kinds of wisdom) are actually attained by one thought". This statement was further expanded by the second patriarch, Hui-Wen, and his student Hui-Sze (514-577), the third patriarch who was also Chih-I's teacher, which formed the early structure of the Three-views theory. This theory later became the root theory of Tien-Tai school but the completed philosophic system of the school was not fully established until Chih-I finished the commentary work on the Lotus Sutra.

This school takes as a premise that all phenomena are an expression of the true suchness (absoluteness) and this absoluteness is expressed in three phenomenon truths. One can only be fully enlightened by achieving the complete understanding of the three truths taught by the Buddha. These three phenomenon truths are:

Dependent reality: A phenomenon is produced by various causes, its essence is devoid of any permanent existence.

Phenomenal existence: This existence is temporary, and has its limitation.

Middle: This truth of the middle is equated with true suchness, and it can not be found elsewhere than in phenomena. According to this truth, Dependent reality and Phenomenal existence are one.

And the only way to obtain the full awareness of the above truths is the Three views (or three insights):

Emptiness: Phenomena posses no independent reality and they can not exist without other factors, therefore nothing is eternal.

Unreality: Although a phenomenon has the apparent existence of phenomena and can be perceived by the senses, because its nature of emptiness, this phenomenon is temporary and unreal.

Middle Way: Since a phenomenon is blended of emptiness and unreality, it is incorrect to view the truth in any of the above two poles. The proper action is to view a phenomenon and its parts as a whole, all phenomena are merged and contain one another.

The practice of this school consists of meditation based on the methods of Chih Kwan. The notion of Chih Kwan puts equal emphasis on the doctrinal and practical aspects which comprises the noble teachings that the Buddha proclaimed during his life. The Chih-Kuan practice contains:

Chih (Samatha, Concentration): This is a technique to subdue those mental factors that fetter man to suffering so the further arising of illusions can be prevented.

Kuan (Vipasyana, Contemplation): Through understanding of the three Phenomenon truths and Three views, enlightenment may be attained in a single spontaneous thought. "The whole world is contained in a mustard seed," and "Three Thousand Words in One Thought" are the famous Tien-Tai theories about how one thought embodies the universality of all things.

The principal works of this school are the " Tien-tai three big books" and " Tien-tai five small books". The Three Big Books are:

The Profound Meaning of Lotus Sutra (Chinese, Fa-Hwa-Shuan-Ye): It uses the title of Lotus Sutra as the base to explore the true meaning of the Buddha's teaching.

The Commentary of Lotus Sutra (Chinese, Fa-Hwa-Wen-Gui): It addresses the commentary of the contents of Lotus Sutra.

Maha(Greater)-Samatha-Vipasyana (Chinese, Mou-Her-Chih-Kwan): It describes the right Chih-Kuan techniques to achieve the three virtues of nirvana, namely the true Dharma body (dharmakaya), wisdom of enlightenment, and liberation from suffering.

The Five Small Books are commentaries on five Mahayana sutras. These sutras are:

The Commentary of the Visualization Of Buddha Amitayus Sutra

The Profound Meaning of Golden-light Sutra

The Commentary of Golden-light Sutra

The Profound Meaning of Kuan-Yin Sutra

The Commentary of Kuan-Yin Sutra

Other important teachings from Chih-I include Six Wondrous Gates of Liberation (Chinese, Liu-Miao-Fa-Men), Smaller-Samatha-Vipasyana (or Beginner's Samatha-Vipasyana), and Gradual Samatha-Vipasyana (or Explanation of the Gradual Dharma Door of the Dhyana Paramita. Chinese, She-Zen-Po-Luo-Mi).

The Tien-Tai school is generally considered a syncretistic school, because it synthesizes different viewpoints of other Buddhist schools from India. It represents an attempt to systematize the teachings of Buddha, to resolve different understanding of teachings arising within Buddhism of different doctrines, and to provide ways of solving metaphysical problems. In order to accomplish these objectives, Chih-I classified the teaching of Buddha into "five periods and eight teachings." It provides a place for the most widely different sutras and regards the Hinayana as well as the Mahayana as an authentic doctrinal expression of the Buddha.

The division of five periods is based on chronological criteria:

The period of the Avatamsaka-sutras

These sutras were taught by the Buddha immediately after attaining his enlightenment. It revealed the greatness of Buddhism that universe is the expression of the true suchness (absoluteness). The target audiences were the Budhisattvas though the teachings were too profound for most of the Buddha's general disciples to grasp. This phase lasted for twenty-one days.

The period of the Agamas-sutra

Because the Buddha's disciples did not understand the principal idea of the teaching during the first period, he then expounded the four noble truths, the eight-fold path, and the teaching of dependent-arising (pratitya-samutpada) as a means to develop the understanding of the truth. This teaching was Agamas and it lasted for twelve years.

The period of the Vaipulya-sutras

In this teaching the Buddha taught the introduction of the Mahayana, he stated the superiority of a Budhisattva over an Arhat, and the unity of Buddha and sentient beings, of absoluteness and relative. This phase lasted for eight years,

The period of the Prajnaparamita-sutra

The Buddha taught his disciples the meaning of emptiness in this period. Three of the central teachings on emptiness are the great, middle-length and shorter Prajnaparamita-sutra (Perfection of Wisdom Sutras). In all of these sutras, a complete explanation of both aspects of the path to Buddhahood, i.e. wisdom and method, was given. The fourth period lasted for twenty-two years.

The period of the Lotus Sutra and Mahaparinirvana-sutra

In the fifth and last period, which corresponds to the last eight years of Buddha's life, he emphasized the absolute identity of all opposites. The teachings during the last period expounded the ultimate and complete truth. It essentially concluded the previous four periods of teachings and stated that the three vehicles (triyana) of the Shravakas, Pratyeka-buddhas, and Bodhisattvas have only provisional validity and all of them will eventually merge into a single vehicle (ekayana) toward the Great Nirvana.

This represents a chronological division of the teaching. The school also holds the view that the Buddha taught the teachings of the five periods simultaneously. The reason why these teachings were viewed differently was because of the disciples' understanding and the methods that the Buddha was using. This leads to a systematization of the Buddha's teaching into eight doctrines: four of which are to be considered from the point of view of method and four from the point of view of content.

These eight teachings, even shown as different paths, are all capable of leading the practitioners to the final enlightenment. And the techniques of achieving nirvana are considered universal because it advocates the notion of universal liberation, which is possible because all beings and things possess Buddha-nature and because they all make use of available means for the realization of enlightenment.

The first group of the teachings is considered from the point of view of method, which includes:

The Sudden method: Which is to be used with the most talented students who understand the truth directly. This is the method of the Avatamsaka sutra.

The Gradual method: Which progresses from elementary to more complex doctrines and includes the Agama, Vaipulya-sutra, and Prajnaparamita-sutra periods. The Lotus Sutra is excluded.

The Secret method: Which is to be used only when addressing individuals. The Buddha's teaching, in this case, was understood only by the selected disciples. Other disciples could have been present, but owing to the supernatural power of the Buddha, they would not have been aware of what he said to them individually.

The Indeterminate method: In which, the individual disciples were attending the same session, they heard and understood the Buddha's words in different ways.

The last two methods were used by the Buddha when he wanted to instruct disciples of different capacities at the same time.

The second group of the teachings is considered from the point of view of content, which includes:

The Hinayana teachings: It is meant for Shravakas and Pratyeka-buddhas.

The Common teaching (common to the Hinayana and the Mahayana): It is meant for the Shravakas, Pratyeka-buddhas, and lower-level Bodhisattvas.

The Special teaching: It is dedicated for the Bodhisattvas.

The Complete (Round) teaching: The teaching of the Middle Way. Any teaching given by the Buddha should be considered as the ultimate teaching regardless of the methods.

The period of the Avatamsaka-sutra included Special and Round teachings. The Agamas-sutra was the only teaching of the Hinayana. The Vaipulya-sutras phase covered all four teachings. The Prajnaparamita-sutra contained Round teaching but also covered Common and Special teachings. Only the Lotus-sutra could be regarded as really the Round teaching.

The Bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara, an important figure from the Lotus Sūtra.

Most scholars regard the Tiantai as one of the first truly Chinese schools of Buddhist Thought. The Schools of Buddhism that had existed in China prior to the emergence of the Tiantai are generally believed to represent direct transplantations from India, with little modification to their basic doctrines and methods. The creation of the Tiantai school signified the maturation and integration of Buddhism in the Chinese context. No longer content to simply translate texts received from Indian sources, Chinese Buddhists began to apply new analyses to old texts, and even to produce new scriptures and commentaries that would attain significant status within the East Asian sphere.

The Tiantai school became doctrinally broad, able to absorb and give rise to other movements within Buddhism. The tradition emphasized both scriptural study and Meditative practice, and taught the rapid Attainment of Buddhahood through observing the Mind.

The school is largely based on the teachings of Zhiyi, Zhanran, and Zhili, who lived between the 6th and 11th centuries in China. These teachers took an approach called "classification of teaching" in an attempt to harmonize the numerous and often contradictory Buddhist texts that had come into China. This was achieved through a particular interpretation of the Lotus Sūtra.

Patriarchs

Due to the use of Nāgārjuna's philosophy of the Middle Way, Nagarjuna is traditionally taken to be the first Patriarch of the Tiantai school.

The sixth century Dhyāna master Huiwen (慧文) is traditionally considered to be the second Patriarch of the Tiantai school. Huiwen studied the works of Nāgārjuna, and is said to have Awakened to the profound meaning of Nāgārjuna's words: "All conditioned Phenomena I speak of as empty, and are but false names which also indicate the mean."

Huiwen later transmitted his teachings to the Dhyāna master Huisi (Ch. 慧思, 515-577 CE), who is traditionally figured as the third Patriarch. During Meditation, he is said to have realized the Lotus Samādhi, indicating Enlightenment and Buddhahood. He authored the text Mahāyāna-śamatha-vipaśyanā.

Venerable Huisi then transmitted his teachings to Śramaṇa Zhiyi (Ch. 智顗, 538-597 CE), who is traditionally figured as the fourth Patriarch of Tiantai, who is said to have practiced the Lotus Samādhi and to have become Enlightened quickly. He authored many treatises such as explanations of the Buddhist texts, and especially systematic manuals of various lengths which explain and enumerate methods of Buddhist practice and Meditation. The above lineage was proposed by Buddhists of later times and do not reflect the popularity of the Monks at that time.

Zhiyi

Most scholars consider Zhiyi to have been the major founder of the Tiantai school, since he did the most to systematize and popularize the doctrines and methods associated with it. At a later date, the school's sixth Patriarch, Zhanran, would compose clarifying commentaries on Zhiyi's writings.

Zhiyi analyzed and organized all the Āgamas and Mahayana Sutras into a system of Five periods and eight types of teachings. For example, many elementary doctrines and bridging concepts had been taught early in The Buddha's advent when the vast majority of the people during his time were not yet ready to grasp the 'ultimate Truth'. These teachings (the Āgamas) were an upaya, or skillful means, were simply an example of The Buddha employing his boundless Wisdom to lead those people towards the Truth. Subsequent teachings delivered to more advanced followers thus represent a more complete and accurate picture of The Buddha's teachings, and did away with some of the philosophical 'crutches' introduced earlier. Zhiyi's classification culminated with the Lotus Sutra, which he held to be the supreme synthesis of Buddhist Doctrine. The difference on Zhiyi's explanation to the Golden Light Sutra caused a debate in Song Dynasty.

Texts

The Tiantai school takes the Lotus Sūtra (Saddharmapuṇḍarīka Sūtra) as the main basis, the MahāPrajñāpāramitā Śāstra of Nāgārjuna as the guide, the Nirvāṇa Sūtra as the support, and the Pañcaviṃśatisāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra for methods of contemplation.

In addition to its doctrinal basis in Indian Buddhist texts, the Tiantai school also emphasizes use of its own Meditation texts which emphasize the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Of the Tiantai Meditation treatises, Zhiyi's Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā (小止観), Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā (摩訶止観), and Six Subtle Dharma Gates (六妙法門) are the most widely read in China.[5] Rujun Wu identifies the work Mahā-śamatha-vipaśyanā of Zhiyi as the seminal Meditation text of the Tiantai school.

Classification of teachings

Tiantai classified The Buddha's teachings in Five periods and Eight teachings. This classification is usually attributed to Chih-i, but is probably a later development. The classification of teachings was also done by other schools, such as the Fivefold Classification of the Huayan school.

Five periods

The Five periods are Five periods in the life of the Buddha in which he delivered different teachings, aimed at different audiences with a different level of understanding:

The Period of Avatamsaka. During twenty-one days after his Enlightenment, The Buddha delivered the Avatamsaka Sutra.

The Period of Agamas. During twelve years, The Buddha preached the Agamas for the Nihayana, including The Four Noble Truths and Dependent origination.

The Period of Vaipulya. During eight years, The Buddha delivered the Mahayana teachings, such as the Vimalakirti Sutra, the Śrīmālādevī Sūtra, the Suvarnaprabhasa Sutra and other Mahayana Sutras.

The Period of Prajna. During twenty-two years, The Buddha explained Emptiness in the Prajnaparamita-Sutras.

The Period of Dharma-pundarik and Nirvana. In the last eight years, The Buddha preached the Doctrine of the One Buddha Vehicle, and delivered the Lotus Sutra and the Nirvana Sutra just before his Death.

Eight teachings

The Eight teachings consist of the Four Doctrines, and the Fourfold Methods.

Four Doctrines

Tripitaka Teaching: the Sutra, Vinaya and Abhidhamma, in which the basic teachings are explained

Shared Teaching: the teaching of Emptiness

Distinctive Teaching: aimed at the Bodhisattva

Perfect Teaching - the Chinese teachings of the Lotus Sutra and the Avatamsaka Sutra

Fourfold Methods

Gradual Teaching, for those with medium or inferior abilities

Sudden Teaching, the Distinctive Teachings and the Complete Teaching for those with superior abilities

Secret Teaching, teachings which are transmitted without the recipient being aware of it

Variable Teaching, no fixed teaching, but various teachings for various persons and circumstances

Teachings

David Chappell lists the most important teachings as the doctrines of:

The Threefold Truth,

The Threefold Contemplation,

The Fourfold Teachings,

The Subtle Dharma,

The Nonconceivable Discernment.

Nan Huaijin, a 20th-century Chán-teacher, summarizes the main teaching of the Tiantai school as the following:

The One Vehicle (Skt. Ekayāna),

The vehicle of attaining Buddhahood, as the main principle;

The three forms of śamatha-vipaśyanā correlated with the Meditative perspectives of Emptiness,

The mean, as the method of cultivating realization.

The Threefold Truth

The Tiantai school took up the principle of The Threefold Truth, derived from Nāgārjuna:

Phenomena are empty of self-nature,

Phenomena exist provisionally from a worldly perspective,

Phenomena are both empty of existence and exist provisionally at once.

The transient World of Phenomena is thus seen as one with the unchanging, undifferentiated substratum of existence. This Doctrine of interpenetration is reflected in the Tiantai teaching of three thousand realms in a single moment of Thought.

The Threefold Truth has its basis in Nāgārjuna:

All things arise through causes and conditions.

That I declare as Emptiness.

It is also a provisional designation.

It is also the meaning of the Middle Path.

Three Contemplations

While the Three Truths are essentially one, they may be recognized separately as one undertakes the Three Contemplations:

The first contemplation involves moving from the World of provisionality to the World of Emptiness, or Shunyata.

The second contemplation is moving back from the World of Emptiness to the World of provisionality with an acceptance thereof.

The third contemplation involves balancing the previous two by following the Middle Path.

The Fourfold Teachings

The Three Contemplations and Threefold Truth in turn Form the basis of the Fourfold Teachings, making them "parallel structures".

Meditation-practice

According to Charles Luk, in China it has been traditionally held that the Meditation methods of the Tiantai are the most systematic and comprehensive of all. Tiantai emphasizes śamatha and vipaśyanā Meditation.

Regarding the functions of śamatha and vipaśyanā in Meditation, Zhiyi writes in his work Concise Śamatha-vipaśyanā:

The attainment of Nirvāṇa is realizable by many methods whose essentials do not go beyond the practice of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Śamatha is the first step to untie all bonds and vipaśyanā is essential to root out Delusion. Śamatha provides nourishment for the preservation of the knowing Mind, and vipaśyanā is the skillful Art of promoting Spiritual understanding. Śamatha is the unsurpassed cause of Samādhi, while vipaśyanā begets Wisdom.

The Tiantai school also places a great emphasis on Mindfulness of Breathing (Skt. ānāpānasmṛti) in accordance with the principles of śamatha and vipaśyanā. Zhiyi classifies breathing into four main categories:

Panting (喘),

Unhurried breathing (風),

Deep and quiet breathing (氣),

Stillness or rest (息).

Zhiyi holds that the first three kinds of breathing are incorrect, while the fourth is correct, and that the breathing should reach stillness and rest.

Influence

David Chappell writes that although the Tiantai school, "has the reputation of being...the most comprehensive and diversified school of Chinese Buddhism, it is almost unknown in the West" despite having a "religious framework that seemed suited to adapt to other cultures, to evolve new practices, and to universalize Buddhism". He attributes this failure of expansion to the school having "narrowed its practice to a small number of Rituals" and because it has "neglected the Intellectual breadth and subtlety of its founder".