Difference between revisions of "Guifeng Zongmi"

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

[[Zongmi]] was deeply affected by both [[Chan]] and [[Huayan]]. He wrote a number of works on the contemporary situation of [[Buddhism]] in Tang [[China]], including critical analyses of [[Chan]] and [[Huayan]], as well as numerous scriptural exegeses. | [[Zongmi]] was deeply affected by both [[Chan]] and [[Huayan]]. He wrote a number of works on the contemporary situation of [[Buddhism]] in Tang [[China]], including critical analyses of [[Chan]] and [[Huayan]], as well as numerous scriptural exegeses. | ||

| − | [[Zongmi]] was deeply interested in both the practical and doctrinal aspects of [[Buddhism]]. He was especially concerned about harmonizing the [[views]] of those that tended toward exclusivity in either [[direction]]. He provided doctrinal classifications of the [[Buddhist teachings]], accounting for the apparent disparities in the [[Buddhist]] [[doctrines]] by categorizing them according to their specific aims. | + | [[Zongmi]] was deeply [[interested]] in both the practical and [[doctrinal]] aspects of [[Buddhism]]. He was especially concerned about harmonizing the [[views]] of those that tended toward exclusivity in either [[direction]]. He provided [[doctrinal]] classifications of the [[Buddhist teachings]], accounting for the apparent disparities in the [[Buddhist]] [[doctrines]] by categorizing them according to their specific aims. |

| − | '''Biography''' | + | '''{{Wiki|Biography}}''' |

Early years (780-810) | Early years (780-810) | ||

[[File:25466 amui.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:25466 amui.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Zongmi]] was born in 780 into the powerful and influential Ho family in Hsi-ch’ung County of present-day central Szechwan. In his early years, he studied the Confucian classics, hoping to for a career in the provincial government. When he was seventeen or eighteen, [[Zongmi]] lost his father and took up [[Buddhist]] studies. In an 811 [[letter]] to a friend, he wrote that for three years he | + | [[Zongmi]] was born in 780 into the {{Wiki|powerful}} and influential Ho family in Hsi-ch’ung County of present-day {{Wiki|central}} Szechwan. In his early years, he studied the {{Wiki|Confucian}} classics, hoping to for a career in the provincial government. When he was seventeen or eighteen, [[Zongmi]] lost his father and took up [[Buddhist]] studies. In an 811 [[letter]] to a friend, he wrote that for three years he |

| − | [G]ave up eating meat, examined [[Buddhist]] scriptures and treatises, became familiar with the [[virtues]] of [[meditation]] and sought out the acquaintance of noted [[monks]]. | + | [G]ave up eating meat, examined [[Buddhist]] [[scriptures]] and treatises, became familiar with the [[virtues]] of [[meditation]] and sought out the acquaintance of noted [[monks]]. |

| − | At the age of twenty-two, he returned to the Confucian classics and deepened his understanding, studying at the I-hsüeh yüan Confucian Academy in Sui-chou. His later writings reveal a detailed familiarity with the Confucian Analects, the Classic of Filial Piety ( Xiao Jing), the Classic of [[Rites]] as well as historical texts and {{Wiki|Taoist}} classics such as the works of Lao tzu. | + | At the age of twenty-two, he returned to the {{Wiki|Confucian}} classics and deepened his [[understanding]], studying at the I-hsüeh yüan {{Wiki|Confucian}} {{Wiki|Academy}} in Sui-chou. His later writings reveal a detailed familiarity with the {{Wiki|Confucian}} {{Wiki|Analects}}, the Classic of Filial Piety ( Xiao Jing), the Classic of [[Rites]] as well as historical texts and {{Wiki|Taoist}} classics such as the works of Lao tzu. |

| − | Chán (804-810) | + | [[Chán]] (804-810) |

At the age of twenty-four, [[Zongmi]] met the [[Chan]] [[master]] Sui-chou {{Wiki|Tao}}-yüan and trained in [[Zen]] [[Buddhism]] for two or three years. He received {{Wiki|Tao}}-yuan’s seal in 807, the year he was fully [[ordained]] as a [[Buddhist monk]]. | At the age of twenty-four, [[Zongmi]] met the [[Chan]] [[master]] Sui-chou {{Wiki|Tao}}-yüan and trained in [[Zen]] [[Buddhism]] for two or three years. He received {{Wiki|Tao}}-yuan’s seal in 807, the year he was fully [[ordained]] as a [[Buddhist monk]]. | ||

[[File:Begtse.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Begtse.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | In his autobiographical summary he states that it was the Sūtra of [[Perfect Enlightenment]] (Yüan-chüeh ching) which led him to [[enlightenment]], his "[[mind]]-ground opened thoroughly [...] It's [the scripture’s] meaning was as clear and bright as the [[heavens]]." Zongmi’s sudden [[awakening]] after reading only two or three pages of the [[scripture]] had a profound impact upon his subsequent [[scholarly]] career. He propounded the necessity of scriptural studies in [[Chan]], and was highly critical of what he saw as the antinomianism of the Hung-chou [[lineage]] derived from Mazu Daoyi ([[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}}: 馬祖道一; simplified {{Wiki|Chinese}}: 马祖道一; pinyin: Mǎzǔ Dàoyī; Wade–Giles : Ma-tsu {{Wiki|Tao}}-yi, 709 CE–788 CE), which practiced "entrusting oneself to act freely according to the nature of one’s [[feelings]]". But Zongmi’s Confucian [[moral]] values never left him and he spent much of his career attempting to integrate Confucian [[ethics]] with [[Buddhism]]. | + | In his autobiographical summary he states that it was the [[Sūtra]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]] (Yüan-chüeh ching) which led him to [[enlightenment]], his "[[mind]]-ground opened thoroughly [...] It's [the scripture’s] [[meaning]] was as clear and bright as the [[heavens]]." Zongmi’s sudden [[awakening]] after reading only two or three pages of the [[scripture]] had a profound impact upon his subsequent [[scholarly]] career. He propounded the necessity of scriptural studies in [[Chan]], and was highly critical of what he saw as the antinomianism of the Hung-chou [[lineage]] derived from Mazu Daoyi ([[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}}: 馬祖道一; simplified {{Wiki|Chinese}}: 马祖道一; pinyin: Mǎzǔ Dàoyī; Wade–Giles : Ma-tsu {{Wiki|Tao}}-yi, 709 CE–788 CE), which practiced "entrusting oneself to act freely according to the nature of one’s [[feelings]]". But Zongmi’s {{Wiki|Confucian}} [[moral]] values never left him and he spent much of his career attempting to integrate {{Wiki|Confucian}} [[ethics]] with [[Buddhism]]. |

Hua-yan (810-816) | Hua-yan (810-816) | ||

| − | In 810, at the age of thirty, [[Zongmi]] met Ling-feng, a [[disciple]] of the preeminent [[Buddhist]] [[scholar]] and [[Huayan]] exegete Ch’eng-kuan (738-839). Ling-feng gave [[Zongmi]] a copy of Ch’eng-kuan’s commentary and subcommentary on the [[Huayan]] Sūtra([[Flower Garland Sutra]]). The two texts were to have a profound impact on Zongmi. He studied these texts and the sūtra with great intensity, declaring later that due to his assiduous efforts, finally "all remaining [[doubts]] were completely washed away." In 812 [[Zongmi]] travelled to the western capital, Chang’an, where he spent two years studying with Ch’eng-kuan, who was not only the undisputed authority on [[Huayan]], but was also highly knowledgeable in [[Chan]], Tientai, the [[Vinaya]] and [[San-lun]]. | + | In 810, at the age of thirty, [[Zongmi]] met Ling-feng, a [[disciple]] of the preeminent [[Buddhist]] [[scholar]] and [[Huayan]] exegete [[Ch’eng-kuan]] (738-839). Ling-feng gave [[Zongmi]] a copy of Ch’eng-kuan’s commentary and subcommentary on the [[Huayan]] [[Sūtra]]([[Flower Garland Sutra]]). The two texts were to have a profound impact on [[Zongmi]]. He studied these texts and the [[sūtra]] with great intensity, declaring later that due to his assiduous efforts, finally "all remaining [[doubts]] were completely washed away." In 812 [[Zongmi]] travelled to the western {{Wiki|capital}}, Chang’an, where he spent two years studying with [[Ch’eng-kuan]], who was not only the undisputed authority on [[Huayan]], but was also highly [[knowledgeable]] in [[Chan]], Tientai, the [[Vinaya]] and [[San-lun]]. |

'''Mount Chung-nan (816-828)''' | '''Mount Chung-nan (816-828)''' | ||

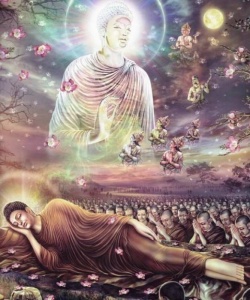

[[File:233 7460.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:233 7460.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Zongmi]] withdrew to Mount Chung-nan, southwest of Chang’an, in 816 and began his [[writing]] career, composing an annotated outline of the Sūtra of [[Perfect Enlightenment]], and a compilation of passages from four commentaries on the sūtra. For the next three years [[Zongmi]] continued his research into [[Buddhism]], reading the entire [[Buddhist canon]], the [[Tripitaka]], and traveling to various [[temples]] on Mount Chung-nan. He returned Chang’an in 819 and continued his studies utilizing the extensive libraries of various [[monasteries]] in the capital city. In late 819 he completed a commentary (shu) and subcommentary (ch’ao) on the Diamond Sūtra. In early 821 he returned to Ts’ao-t’ang [[temple]] beneath Kuei Peak and hence became known as [[Guifeng Zongmi]] (WG:Kuei-feng [[Tsung-mi]]. In mid-823 he finally finished his own commentary on the text that had led to his first [[awakening]] [[experience]], Sūtra of [[Perfect Enlightenment]], and the culmination of a [[vow]] he had made some fifteen years earlier. For the next five years [[Zongmi]] continued [[writing]] and studying on Mount Chung-nan as his [[fame]] grew. | + | [[Zongmi]] withdrew to Mount Chung-nan, {{Wiki|southwest}} of Chang’an, in 816 and began his [[writing]] career, composing an annotated outline of the [[Sūtra]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]], and a compilation of passages from four commentaries on the [[sūtra]]. For the next three years [[Zongmi]] continued his research into [[Buddhism]], reading the entire [[Buddhist canon]], the [[Tripitaka]], and traveling to various [[temples]] on Mount Chung-nan. He returned Chang’an in 819 and continued his studies utilizing the extensive libraries of various [[monasteries]] in the {{Wiki|capital}} city. In late 819 he completed a commentary (shu) and subcommentary (ch’ao) on the [[Diamond Sūtra]]. In early 821 he returned to Ts’ao-t’ang [[temple]] beneath Kuei Peak and hence became known as [[Guifeng Zongmi]] (WG:Kuei-feng [[Tsung-mi]]. In mid-823 he finally finished his own commentary on the text that had led to his first [[awakening]] [[experience]], [[Sūtra]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]], and the culmination of a [[vow]] he had made some fifteen years earlier. For the next five years [[Zongmi]] continued [[writing]] and studying on Mount Chung-nan as his [[fame]] grew. |

| − | '''Capital city (828-835''') | + | '''{{Wiki|Capital}} city (828-835''') |

| − | He was summoned to the capital in 828 by {{Wiki|Emperor Wenzong}} (r. 826-840) and awarded the purple robe and the honorific title "Great [[Worthy]]" (ta-te; bhadanta). The two years he spent in the capital were significant for Zongmi. He was now a nationally honoured [[Chan]] [[master]] with extensive contacts among the literati of the day. He turned his considerable [[knowledge]] and intellect towards [[writing]] for a broader audience rather than the technical {{Wiki|exegetical}} works he had produced for a limited readership of [[Buddhist]] specialists. His [[scholarly]] efforts became directed towards the [[intellectual]] issues of the day and much of his subsequent work was produced at the appeals of assorted literati of the day. He began collecting every extant [[Chan]] text in circulation with the goal of producing a [[Chan]] [[canon]] to create a new section of the [[Buddhist canon]]. This work is lost but the title, Collection of Expressions of the [[Zen]] [[Chan]] Source (Ch’an-yuan chu-ch’uan chi,禪源諸詮集) remains. | + | He was summoned to the {{Wiki|capital}} in 828 by {{Wiki|Emperor Wenzong}} (r. 826-840) and awarded the purple robe and the honorific title "[[Great]] [[Worthy]]" (ta-te; [[bhadanta]]). The two years he spent in the {{Wiki|capital}} were significant for [[Zongmi]]. He was now a nationally honoured [[Chan]] [[master]] with extensive contacts among the literati of the day. He turned his considerable [[knowledge]] and {{Wiki|intellect}} towards [[writing]] for a broader audience rather than the technical {{Wiki|exegetical}} works he had produced for a limited readership of [[Buddhist]] specialists. His [[scholarly]] efforts became directed towards the [[intellectual]] issues of the day and much of his subsequent work was produced at the appeals of assorted literati of the day. He began collecting every extant [[Chan]] text in circulation with the goal of producing a [[Chan]] [[canon]] to create a new section of the [[Buddhist canon]]. This work is lost but the title, Collection of Expressions of the [[Zen]] [[Chan]] Source (Ch’an-yuan chu-ch’uan chi,禪源諸詮集) {{Wiki|remains}}. |

Last years (835-841) | Last years (835-841) | ||

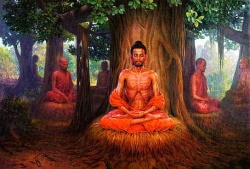

[[File:001 5782c.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:001 5782c.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | It was Zongmi’s association with the great and the powerful that led to his downfall in 835 in an event known as the {{Wiki|Ganlu Incident}}. A high official and friend of Zongmi, Li Xun, in connivance with Emperor Wenzong and the general {{Wiki|Zheng Zhu}}, attempted to curb the [[power]] of the court eunuchs by massacring them all. The plot failed and Li Xun fled to Mount Chung-nan seeking [[refuge]] with Zongmi. Li Xun was quickly captured and executed and [[Zongmi]] was arrested and tried for treason. Impressed with Zongmi’s bravery in the face of execution, the powerful eunuch Yu Hongzhi (魚弘志) persuaded fellow powerful eunuch {{Wiki|Qiu Shiliang}} to spare Zongmi. | + | It was Zongmi’s association with the great and the {{Wiki|powerful}} that led to his downfall in 835 in an event known as the {{Wiki|Ganlu Incident}}. A high official and friend of [[Zongmi]], Li Xun, in connivance with [[Emperor]] Wenzong and the {{Wiki|general}} {{Wiki|Zheng Zhu}}, attempted to curb the [[power]] of the court eunuchs by massacring them all. The plot failed and Li Xun fled to Mount Chung-nan seeking [[refuge]] with [[Zongmi]]. Li Xun was quickly captured and executed and [[Zongmi]] was arrested and tried for treason. Impressed with Zongmi’s bravery in the face of execution, the {{Wiki|powerful}} {{Wiki|eunuch}} Yu Hongzhi (魚弘志) persuaded fellow {{Wiki|powerful}} {{Wiki|eunuch}} {{Wiki|Qiu Shiliang}} to spare [[Zongmi]]. |

| − | [[Nothing]] is known about Zongmi’s activities after this event. [[Zongmi]] [[died]] in the [[zazen]] [[posture]] on February 1, 841 in Chang-an. He was cremated on March 4 at Guifeng [[temple]]. Twelve years later he was awarded the posthumous title Samādi-Prajnā [[Chan]] [[Master]] and his remains were interred in a [[stupa]] called Blue [[Lotus]]. | + | [[Nothing]] is known about Zongmi’s [[activities]] after this event. [[Zongmi]] [[died]] in the [[zazen]] [[posture]] on February 1, 841 in Chang-an. He was {{Wiki|cremated}} on March 4 at Guifeng [[temple]]. Twelve years later he was awarded the posthumous title Samādi-Prajnā [[Chan]] [[Master]] and his {{Wiki|remains}} were interred in a [[stupa]] called Blue [[Lotus]]. |

[[Philosophy]] | [[Philosophy]] | ||

| − | Zongmi’s lifelong work was the attempt to incorporate differing and sometimes conflicting value systems into an integrated framework that could bridge not only the differences between [[Buddhism]] and the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Taoism}} and {{Wiki|Confucianism}}, but also within [[Buddhist]] theory itself. | + | Zongmi’s lifelong work was the attempt to incorporate differing and sometimes conflicting value systems into an integrated framework that could bridge not only the differences between [[Buddhism]] and the [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Taoism}} and {{Wiki|Confucianism}}, but also within [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|theory}} itself. |

{{Wiki|Confucianism}}, {{Wiki|Taoism}}, [[Buddhism]] | {{Wiki|Confucianism}}, {{Wiki|Taoism}}, [[Buddhism]] | ||

| − | Much of Zongmi’s work was concerned with providing a dialogue between the three [[religions]] of [[China]]: {{Wiki|Confucianism}}, {{Wiki|Taoism}} and [[Buddhism]]. He saw all three as expedients, functioning within a particular historical context and although he placed [[Buddhism]] as revealing the [[highest truth]] of the three, this had [[nothing]] to do with the level of understanding of the three sages, {{Wiki|Confucius}}, {{Wiki|Lao-tzu}} and [[Buddha]], (who [[Zongmi]] saw as equally [[enlightened]]) and everything to do with the particular circumstances in which the three lived and taught. As [[Zongmi]] said: | + | Much of Zongmi’s work was concerned with providing a dialogue between the three [[religions]] of [[China]]: {{Wiki|Confucianism}}, {{Wiki|Taoism}} and [[Buddhism]]. He saw all three as expedients, functioning within a particular historical context and although he placed [[Buddhism]] as revealing the [[highest truth]] of the three, this had [[nothing]] to do with the level of [[understanding]] of the three [[sages]], {{Wiki|Confucius}}, {{Wiki|Lao-tzu}} and [[Buddha]], (who [[Zongmi]] saw as equally [[enlightened]]) and everything to do with the particular circumstances in which the three lived and taught. As [[Zongmi]] said: |

[[File:22vnshou.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:22vnshou.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Since encouraging the myriad practices, admonishing against [[evil]], and promoting good contribute in common to order, the three teachings should all be followed and practiced. [However] if it be a matter of investigating the myriad [[phenomena]], exhausting principle, [[realizing]] the nature, and reaching the original source, then [[Buddhism]] alone is the [[ultimate]] judgment. | + | Since encouraging the myriad practices, admonishing against [[evil]], and promoting good contribute in common to [[order]], the three teachings should all be followed and practiced. [However] if it be a [[matter]] of investigating the myriad [[phenomena]], exhausting {{Wiki|principle}}, [[realizing]] the nature, and reaching the original source, then [[Buddhism]] alone is the [[ultimate]] judgment. |

| − | Zongmi’s early training in {{Wiki|Confucianism}} never left him and he tried to create a {{Wiki|syncretic}} framework where Confucian [[moral]] principles could be integrated within the [[Buddhist teachings]]. | + | Zongmi’s early training in {{Wiki|Confucianism}} never left him and he tried to create a {{Wiki|syncretic}} framework where {{Wiki|Confucian}} [[moral]] {{Wiki|principles}} could be integrated within the [[Buddhist teachings]]. |

'''Sudden and Gradual [[Enlightenment]]''' | '''Sudden and Gradual [[Enlightenment]]''' | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

Coming from the Southern [[Chan]] [[tradition]], [[Zongmi]] advocated the Southern teachings of sudden [[enlightenment]]. But he also saw both as according with the teachings of the [[Buddha]]. He wrote: | Coming from the Southern [[Chan]] [[tradition]], [[Zongmi]] advocated the Southern teachings of sudden [[enlightenment]]. But he also saw both as according with the teachings of the [[Buddha]]. He wrote: | ||

| − | It is only because of variations in the style of the [[World]] Honored One’s exposition of the teachings that there are sudden expositions in accordance with the [[truth]] and gradual expositions in accordance with the capacities [of beings]…this does not mean that there is a separate sudden and gradual [teaching]. | + | It is only [[because of]] variations in the style of the [[World]] Honored One’s exposition of the teachings that there are sudden expositions in accordance with the [[truth]] and gradual expositions in accordance with the capacities [of [[beings]]]…this does not mean that there is a separate sudden and gradual [[[teaching]]]. |

[[File:00x200as.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:00x200as.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Although the sudden teaching reveals the [[truth]] directly, and results in a "sudden" understanding that all beings are [[Buddhas]], this does not mean that one attained [[Buddhahood]] rightaway. Hence, [[Zongmi]] advocated "sudden [[enlightenment]]" followed by "gradual cultivation". This gradual cultivation was to eliminate all remaining traces of [[defilements]] of the [[mind]], that prevented one from fully integrating one’s intrinsic [[Buddha-nature]] into actual {{Wiki|behaviour}}. | + | Although the sudden [[teaching]] reveals the [[truth]] directly, and results in a "sudden" [[understanding]] that all [[beings]] are [[Buddhas]], this does not mean that one attained [[Buddhahood]] rightaway. Hence, [[Zongmi]] advocated "sudden [[enlightenment]]" followed by "gradual cultivation". This gradual cultivation was to eliminate all remaining traces of [[defilements]] of the [[mind]], that prevented one from fully integrating one’s intrinsic [[Buddha-nature]] into actual {{Wiki|behaviour}}. |

| − | To explain this, [[Zongmi]] used the metaphor of water and waves found in the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] [[scripture]]. The essential [[tranquil]] nature of water which reflects all things (intrinsic [[enlightenment]]) is disturbed by the winds of [[ignorance]] (unenlightenment, [[delusion]]). Although the wind may stop suddenly (sudden [[enlightenment]]), the disturbing waves subside only gradually (gradual cultivation) until all motion ceases and the water once again reflects its intrinsic nature ([[Buddhahood]]). However, whether disturbed by [[ignorance]] or not, the fundamental nature of the water (i.e., the [[mind]]) never changes. | + | To explain this, [[Zongmi]] used the {{Wiki|metaphor}} of [[water]] and waves found in the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] [[scripture]]. The [[essential]] [[tranquil]] nature of [[water]] which reflects all things (intrinsic [[enlightenment]]) is disturbed by the winds of [[ignorance]] (unenlightenment, [[delusion]]). Although the [[wind]] may stop suddenly (sudden [[enlightenment]]), the disturbing waves subside only gradually (gradual cultivation) until all motion ceases and the [[water]] once again reflects its intrinsic nature ([[Buddhahood]]). However, whether disturbed by [[ignorance]] or not, the fundamental nature of the [[water]] (i.e., the [[mind]]) never changes. |

| − | Classification of teachings | + | {{Wiki|Classification}} of teachings |

| − | As with many [[Buddhist]] [[scholars]] of the day, doctrinal classification (p’an chiao) was an integral part of Zongmi’s work. Zongmi’s "systematic classification of [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] is itself a theory of the [[Buddhist path]] (mārga)." | + | As with many [[Buddhist]] [[scholars]] of the day, [[doctrinal]] {{Wiki|classification}} (p’an chiao) was an integral part of Zongmi’s work. Zongmi’s "systematic {{Wiki|classification}} of [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]] is itself a {{Wiki|theory}} of the [[Buddhist path]] (mārga)." |

| − | He provided a critique of the various practices which reveal not only the nature of [[Chan]] in {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}}, but also Zongmi’s understanding of [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]]. | + | He provided a critique of the various practices which reveal not only the nature of [[Chan]] in {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}}, but also Zongmi’s [[understanding]] of [[Buddhist]] [[doctrine]]. |

The [[Buddha]]'s Teachings | The [[Buddha]]'s Teachings | ||

[[File:221.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:221.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Zongmi]] arranged the Buddha’s teachings into five categories: | + | [[Zongmi]] arranged the [[Buddha’s teachings]] into five categories: |

| − | The teaching of men and [[gods]], | + | The [[teaching]] of men and [[gods]], |

The teachings of the [[Hinayana]], | The teachings of the [[Hinayana]], | ||

| − | The teaching of {{Wiki|phenomenal}} appearances, | + | The [[teaching]] of {{Wiki|phenomenal}} [[appearances]], |

| − | The teaching of the negation of intrinsic {{Wiki|phenomenal}} appearances and | + | The [[teaching]] of the {{Wiki|negation}} of intrinsic {{Wiki|phenomenal}} [[appearances]] and |

| − | The teaching that reveals the true nature (intrinsic [[enlightenment]]). | + | The [[teaching]] that reveals the [[true nature]] (intrinsic [[enlightenment]]). |

| − | The "true nature" is the [[tathagatagarbha]] or [[Buddha nature]], which is emphasised in Chán. In giving this teaching the highest position, [[Zongmi]] altered the classification of Fa-yan, who regarded the [[Hua-yen]] teachings to be the supreme teachings and established the common denominator of [[Chan]] and Huayen teachings within the "One Vehicle" (ekayana). | + | The "[[true nature]]" is the [[tathagatagarbha]] or [[Buddha nature]], which is emphasised in [[Chán]]. In giving this [[teaching]] the [[highest]] position, [[Zongmi]] altered the {{Wiki|classification}} of Fa-yan, who regarded the [[Hua-yen]] teachings to be the [[supreme]] teachings and established the common denominator of [[Chan]] and [[Huayen]] teachings within the "One [[Vehicle]]" ([[ekayana]]). |

| − | '''Chán teachings''' | + | '''[[Chán]] teachings''' |

| − | Zongmi’s classification also included the various categories of [[Chan]]. He distinguished five categories of Chán-practice: | + | Zongmi’s {{Wiki|classification}} also included the various categories of [[Chan]]. He distinguished five categories of Chán-practice: |

[[File:Bhikkhunis.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Bhikkhunis.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

[[Bon]]-pu [[Zen]], aimed at improvement of personal well-being | [[Bon]]-pu [[Zen]], aimed at improvement of personal well-being | ||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

Saijojo [[Zen]], expressing [[Buddhanature]] in daily [[life]], using shikantasa | Saijojo [[Zen]], expressing [[Buddhanature]] in daily [[life]], using shikantasa | ||

| − | Analysis of [[Mind]] | + | [[Analysis]] of [[Mind]] |

| − | [[Zongmi]] saw [[enlightenment]] and its opposite, [[delusion]], as ten reciprocal steps that are not so much separate processes, but parallel processes moving in opposite [[directions]]. | + | [[Zongmi]] saw [[enlightenment]] and its {{Wiki|opposite}}, [[delusion]], as ten reciprocal steps that are not so much separate {{Wiki|processes}}, but parallel {{Wiki|processes}} moving in {{Wiki|opposite}} [[directions]]. |

| − | [[Zongmi]] follows the One Vehicle interpretation of the [[Yogacara]] analysis of the [[Eight Consciousnesses]] that is found in the [[Lankavatara Sutra]] and the Treatise on the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] in the [[Mahayana]], in describing the {{Wiki|phenomenology}} of the [[mind]]. | + | [[Zongmi]] follows the One [[Vehicle]] interpretation of the [[Yogacara]] [[analysis]] of the [[Eight Consciousnesses]] that is found in the [[Lankavatara Sutra]] and the Treatise on the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] in the [[Mahayana]], in describing the {{Wiki|phenomenology}} of the [[mind]]. |

| − | In Zongmi's [[vision]], the Real [[Mind]] is the true nature which is revealed at the moment of [[awakening]]. Before this [[awakening]], True [[Mind]] is deluded by [[thoughts]] and wrong visions. The {{Wiki|phenomenal}} appearance of this true [[mind]] is the [[tathagatagarbha]], and it's deluded manifestation is the [[alaya-vijnana]], or [[citta]], the [[eighth consciousness]] of [[Yogacara]]. From this deluded [[consciousness]] springs [[manas]], the {{Wiki|grasping}} [[consciousness]], which is the [[seventh consciousness]]. From there springs the {{Wiki|cognitive}} [[mind]] ([[sixth consciousness]]) and the five [[sense]]-[[consciousnesses]]. | + | In Zongmi's [[vision]], the {{Wiki|Real}} [[Mind]] is the [[true nature]] which is revealed at the moment of [[awakening]]. Before this [[awakening]], True [[Mind]] is deluded by [[thoughts]] and wrong visions. The {{Wiki|phenomenal}} appearance of this true [[mind]] is the [[tathagatagarbha]], and it's deluded [[manifestation]] is the [[alaya-vijnana]], or [[citta]], the [[eighth consciousness]] of [[Yogacara]]. From this deluded [[consciousness]] springs [[manas]], the {{Wiki|grasping}} [[consciousness]], which is the [[seventh consciousness]]. From there springs the {{Wiki|cognitive}} [[mind]] ([[sixth consciousness]]) and the five [[sense]]-[[consciousnesses]]. |

| − | Criticism of Chán-schools | + | [[Criticism]] of Chán-schools |

[[File:011664 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:011664 n.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | [[Zongmi]] gave critiques on seven [[Chan]] schools in his Prolegomenon to the Collection of Expressions of the [[Zen]] Source and although he promoted his own Ho-tse school as exemplifying the highest practice, his accounts of the other schools were balanced and unbiased. It is clear from his writings that in many cases he visited the various [[Chan]] [[monasteries]] he wrote about and took notes of his discussions with [[teachers]] and adapts. His work had an enduring [[influence]] on the adaptation of [[Indian Buddhism]] to the [[philosophy]] of [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}} culture. The writings that remain have proved to be an invaluable source for modern [[scholars]] of the history of the development of [[Buddhism]] in [[China]]. | + | [[Zongmi]] gave critiques on seven [[Chan]] schools in his Prolegomenon to the Collection of Expressions of the [[Zen]] Source and although he promoted his own Ho-tse school as exemplifying the [[highest]] practice, his accounts of the other schools were balanced and unbiased. It is clear from his writings that in many cases he visited the various [[Chan]] [[monasteries]] he wrote about and took notes of his discussions with [[teachers]] and adapts. His work had an enduring [[influence]] on the [[adaptation]] of [[Indian Buddhism]] to the [[philosophy]] of [[traditional]] {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|culture}}. The writings that remain have proved to be an invaluable source for {{Wiki|modern}} [[scholars]] of the {{Wiki|history}} of the development of [[Buddhism]] in [[China]]. |

Hung-chou school | Hung-chou school | ||

| − | [[Zongmi]] was critical of [[Chan]] sects that seemed to ignore the [[moral]] order of [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Confucianism}}. For example, while he saw the Northern line as believing "everything as altogether false", [[Zongmi]] claimed the Hung-chou [[tradition]], derived from Mazu Daoyi (709-788), believed "everything as altogether true". | + | [[Zongmi]] was critical of [[Chan]] sects that seemed to ignore the [[moral]] [[order]] of [[traditional]] [[Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Confucianism}}. For example, while he saw the Northern line as believing "everything as altogether false", [[Zongmi]] claimed the Hung-chou [[tradition]], derived from Mazu Daoyi (709-788), believed "everything as altogether true". |

| − | According to Zongmi, the {{Wiki|Hung-chou school}} teaching led to a radical nondualism that believed that all [[actions]], good or bad, as expressing essential [[Buddha-nature]], denying the need for [[spiritual]] cultivation and [[moral]] [[discipline]]. This was a dangerously antinomian [[view]] as it eliminated all [[moral]] distinctions and validated any [[actions]] as expressions of the essence of [[Buddha-nature]]. | + | According to [[Zongmi]], the {{Wiki|Hung-chou school}} [[teaching]] led to a radical [[nondualism]] that believed that all [[actions]], good or bad, as expressing [[essential]] [[Buddha-nature]], denying the need for [[spiritual]] cultivation and [[moral]] [[discipline]]. This was a dangerously antinomian [[view]] as it eliminated all [[moral]] distinctions and validated any [[actions]] as expressions of the [[essence]] of [[Buddha-nature]]. |

| − | While [[Zongmi]] [[acknowledged]] that the essence of [[Buddha-nature]] and its functioning in the day-to-day [[reality]] are but [[difference]] aspects of the same [[reality]], he insisted that there is a [[difference]]. To avoid the [[dualism]] he saw in the Northern Line and the radical nondualism and antinomianism of the Hung-chou school, Zongmi’s {{Wiki|paradigm}} preserved "an [[ethically]] critical [[duality]] within a larger {{Wiki|ontological}} unity", an {{Wiki|ontology}} which he claimed was lacking in Hung-chou [[Chan]]. | + | While [[Zongmi]] [[acknowledged]] that the [[essence]] of [[Buddha-nature]] and its functioning in the day-to-day [[reality]] are but [[difference]] aspects of the same [[reality]], he insisted that there is a [[difference]]. To avoid the [[dualism]] he saw in the Northern Line and the radical [[nondualism]] and antinomianism of the Hung-chou school, Zongmi’s {{Wiki|paradigm}} preserved "an [[ethically]] critical [[duality]] within a larger {{Wiki|ontological}} unity", an {{Wiki|ontology}} which he claimed was lacking in Hung-chou [[Chan]]. |

| − | Northern Chán | + | Northern [[Chán]] |

[[File:Buddha as Siddhartha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha as Siddhartha.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Zongmi’s critique of Northern [[Chan]] was based on its practice of removing [[impurities]] of the [[mind]] to reach [[enlightenment]]. [[Zongmi]] criticized this on the basis that the Northern school was under the misconception that [[impurities]] were "real" as opposed to "empty" (i.e., lack any independent [[reality]] of their own) and therefore this was a [[dualistic]] teaching. Zongmi, on the other hand, saw [[impurities]] of the [[mind]] as intrinsically "empty" and naturally removable by the intrinsically pure nature of the [[mind]]. This understanding of [[Zongmi]] came from the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] [[scripture]] which espoused the [[tathagatagarbha]] [[doctrine]] of the intrinsically [[enlightened]] nature possessed by all beings. | + | Zongmi’s critique of Northern [[Chan]] was based on its practice of removing [[impurities]] of the [[mind]] to reach [[enlightenment]]. [[Zongmi]] criticized this on the basis that the [[Northern school]] was under the misconception that [[impurities]] were "{{Wiki|real}}" as opposed to "[[empty]]" (i.e., lack any independent [[reality]] of their own) and therefore this was a [[dualistic]] [[teaching]]. [[Zongmi]], on the other hand, saw [[impurities]] of the [[mind]] as intrinsically "[[empty]]" and naturally removable by the intrinsically [[pure]] nature of the [[mind]]. This [[understanding]] of [[Zongmi]] came from the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] [[scripture]] which espoused the [[tathagatagarbha]] [[doctrine]] of the intrinsically [[enlightened]] nature possessed by all [[beings]]. |

Ox-head school | Ox-head school | ||

| − | His criticism of another prominent [[Chan]] [[lineage]] of the time, the Ox-head School, was also based on the tathāgatagarbha [[doctrine]] but in this case [[Zongmi]] saw their teaching as a one-sided understanding of [[emptiness]]. He claimed that the Ox-head School taught "no [[mind]]" (i.e., the [[emptiness]] of [[mind]]) but did not recognize the functioning of the [[mind]], assuming that the intrinsically [[enlightened]] nature is likewise "empty" and "that there is [[nothing]] to be [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognized]]". [[Zongmi]] went on to say, "we know that this teaching merely destroys our [[attachment]] to [[feelings]] but does not yet reveal the nature that is true and luminous". | + | His [[criticism]] of another prominent [[Chan]] [[lineage]] of the [[time]], the Ox-head School, was also based on the [[tathāgatagarbha]] [[doctrine]] but in this case [[Zongmi]] saw their [[teaching]] as a one-sided [[understanding]] of [[emptiness]]. He claimed that the Ox-head School taught "no [[mind]]" (i.e., the [[emptiness]] of [[mind]]) but did not [[recognize]] the functioning of the [[mind]], assuming that the intrinsically [[enlightened]] nature is likewise "[[empty]]" and "that there is [[nothing]] to be [[Wikipedia:Cognition|cognized]]". [[Zongmi]] went on to say, "we know that this [[teaching]] merely destroys our [[attachment]] to [[feelings]] but does not yet reveal the nature that is true and luminous". |

Writings | Writings | ||

| − | Zongmi's writings were extensive and influential. There is no certainty about the quantity of Zongmi’s writings. Zongmi’s epitaph, written by P’ei Hsiu, (787?-860) listed over ninety fascicles. Tsan-ning’s (919-1001) biography claimed over two hundred. | + | Zongmi's writings were extensive and influential. There is no certainty about the quantity of Zongmi’s writings. Zongmi’s epitaph, written by P’ei Hsiu, (787?-860) listed over ninety fascicles. Tsan-ning’s (919-1001) {{Wiki|biography}} claimed over two hundred. |

[[File:390796148.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:390796148.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | For modern [[scholars]], [[Zongmi]] provides the "most valuable sources on {{Wiki|Tang dynasty}} [[Zen]]. There is no other extant source even remotely as informative". | + | For {{Wiki|modern}} [[scholars]], [[Zongmi]] provides the "most valuable sources on {{Wiki|Tang dynasty}} [[Zen]]. There is no other extant source even remotely as informative". |

| − | Unfortunately, many of Zongmi’s works are lost, including his Collected Writings on the Source of Ch’an (Ch’an-yüan chu-ch’üan-chi) which would provide modern [[scholars]] with an invaluable source to reconstruct {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} [[Chan]]. | + | Unfortunately, many of Zongmi’s works are lost, including his Collected Writings on the Source of [[Ch’an]] (Ch’an-yüan chu-ch’üan-chi) which would provide {{Wiki|modern}} [[scholars]] with an invaluable source to reconstruct {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} [[Chan]]. |

Commentary on the [[Sutra]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]] | Commentary on the [[Sutra]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]] | ||

| − | Zongmi's first major work was his commentary and subcommentary on Sūtra of [[Perfect Enlightenment]], completed in 823-824. The subcommentary contains extensive {{Wiki|data}} on the teachings, the ideas and practices on the seven houses of [[Chan]]. These {{Wiki|data}} are derived from personal [[experience]] and observations. These observations provide excellent sources on {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} [[Chan]] for modern studies. | + | Zongmi's first major work was his commentary and subcommentary on [[Sūtra]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]], completed in 823-824. The subcommentary contains extensive {{Wiki|data}} on the teachings, the [[ideas]] and practices on the seven houses of [[Chan]]. These {{Wiki|data}} are derived from personal [[experience]] and observations. These observations provide {{Wiki|excellent}} sources on {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} [[Chan]] for {{Wiki|modern}} studies. |

Chart of [[Zen]] Succession | Chart of [[Zen]] Succession | ||

[[File:Buddha vairocana.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Buddha vairocana.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The Chart of the [[Master]]-[[Disciple]] Succession of the [[Chan]] Gate That Has Transmitted the [[Mind]]-Ground in [[China]] (Chung-hua ch’uan-hsin-ti ch’an-men shih-tzu ch’eng-his t’u), was written at the request of P’ei Hsiu sometime between 830 and 833. The work clarifies the major Ch’an [[traditions]] of the Tang era. It contains detailed critiques of the Northern School, the Ox-head School and the two branches of Southern [[Chan]], the Hung-chou and his own Ho-tse (Heze) lines. | + | The Chart of the [[Master]]-[[Disciple]] Succession of the [[Chan]] Gate That Has Transmitted the [[Mind]]-Ground in [[China]] (Chung-hua ch’uan-hsin-ti ch’an-men shih-tzu ch’eng-his t’u), was written at the request of P’ei Hsiu sometime between 830 and 833. The work clarifies the major [[Ch’an]] [[traditions]] of the Tang {{Wiki|era}}. It contains detailed critiques of the [[Northern School]], the Ox-head School and the two branches of Southern [[Chan]], the Hung-chou and his own Ho-tse (Heze) lines. |

The Prolegomenon | The Prolegomenon | ||

| − | The Prolegomenon to the Collection of Expressions of the [[Zen]] Source(also known as the [[Chan]] Preface) (Ch’an-yuan chu-ch’uan-chi tu-hsu) was written around 833. It provides a theoretical basis for Zongmi’s [[vision]] of the correlation between [[Chan]] and the [[Buddhist scriptures]]. It gives accounts of the several [[lineages]] extant at the time, many of which had [[died]] out by the time of the Song Dynasty (960-1279). In this preface, [[Zongmi]] says that he had assembled the contemporary [[Chan]] practices and teachings into ten categories. Unfortunately, the collection itself is lost, and only the preface [[exists]]. | + | The Prolegomenon to the Collection of Expressions of the [[Zen]] Source(also known as the [[Chan]] Preface) (Ch’an-yuan chu-ch’uan-chi tu-hsu) was written around 833. It provides a {{Wiki|theoretical}} basis for Zongmi’s [[vision]] of the correlation between [[Chan]] and the [[Buddhist scriptures]]. It gives accounts of the several [[lineages]] extant at the [[time]], many of which had [[died]] out by the [[time]] of the {{Wiki|Song Dynasty}} (960-1279). In this preface, [[Zongmi]] says that he had assembled the contemporary [[Chan]] practices and teachings into ten categories. Unfortunately, the collection itself is lost, and only the preface [[exists]]. |

On the Original Nature of Man | On the Original Nature of Man | ||

Zongmi's Inquiry into the Origin of [[Humanity]], (or On the Original Nature of Man, or The [[Debate]] on an Original [[Person]]) (原人論 Yüan jen lun) was written sometime between 828 and 835. This essay became one of his best-known works. | Zongmi's Inquiry into the Origin of [[Humanity]], (or On the Original Nature of Man, or The [[Debate]] on an Original [[Person]]) (原人論 Yüan jen lun) was written sometime between 828 and 835. This essay became one of his best-known works. | ||

| − | It surveys the current major [[Buddhist teachings]] of the day, as well as Confucian and {{Wiki|Taoist}} teachings. It not only shows how [[Buddhism]] is superior to the native {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[philosophies]], but also presents a hierarchy of the profundity of the [[Buddhist]] schools. [[Zongmi]] criticizes {{Wiki|Confucianism}} for not having an adequate [[moral]] system or explanation of [[causation]]. He holds up the [[Buddhist]] [[view]] of [[karma]] as the superior system of [[moral]] responsibility. | + | It surveys the current major [[Buddhist teachings]] of the day, as well as {{Wiki|Confucian}} and {{Wiki|Taoist}} teachings. It not only shows how [[Buddhism]] is {{Wiki|superior}} to the native {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[philosophies]], but also presents a {{Wiki|hierarchy}} of the profundity of the [[Buddhist]] schools. [[Zongmi]] criticizes {{Wiki|Confucianism}} for not having an adequate [[moral]] system or explanation of [[causation]]. He holds up the [[Buddhist]] [[view]] of [[karma]] as the {{Wiki|superior}} system of [[moral]] responsibility. |

De Bary writes, | De Bary writes, | ||

| − | Here [[Tsung-mi]]'s own [[spiritual]] development and his [[consideration]] of alternative [[philosophies]] are clearly reflected, as is his [[awareness]] of the need to defend his new [[faith]] against critics upholding {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[tradition]] against [[Buddhism]] It has been said that [[Tsung-mi]] wrote this treatise as an answer to the famous essays On the original Nature of Man (Yuan jen) and On the {{Wiki|Tao}} (Yuan {{Wiki|tao}}) by his contemporary Han Yu (768-824), leader of the Confucian resurgence against [[Buddhism]]. | + | Here [[Tsung-mi]]'s own [[spiritual]] development and his [[consideration]] of alternative [[philosophies]] are clearly reflected, as is his [[awareness]] of the need to defend his new [[faith]] against critics upholding {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[tradition]] against [[Buddhism]] It has been said that [[Tsung-mi]] wrote this treatise as an answer to the famous essays On the original Nature of Man (Yuan jen) and On the {{Wiki|Tao}} (Yuan {{Wiki|tao}}) by his contemporary Han Yu (768-824), leader of the {{Wiki|Confucian}} resurgence against [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | However, his goal was not to wholly denigrate or invalidate the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[philosophies]], but to integrate them into [[Buddhist teachings]] to reach a greater understanding of how the [[human]] [[condition]] came into being. | + | However, his goal was not to wholly denigrate or invalidate the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[philosophies]], but to integrate them into [[Buddhist teachings]] to reach a [[greater]] [[understanding]] of how the [[human]] [[condition]] came into {{Wiki|being}}. |

The [[writing]] style is simple and straightforward, and the content not overly technical, making the work accessible to non-[[Buddhist]] intellectuals of the day. | The [[writing]] style is simple and straightforward, and the content not overly technical, making the work accessible to non-[[Buddhist]] intellectuals of the day. | ||

Commentary on the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] | Commentary on the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] | ||

| − | The undated commentary (Ch’i-hsin lun shu) on the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] was probably written between 823 and 828. Although [[Zongmi]] is [[recognized]] as a [[Huayan]] [[patriarch]], he considered the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] [[scripture]] to exemplify the highest teaching, displacing the [[Huayan]] Sūtra as the supreme [[Buddhist]] teaching. | + | The undated commentary (Ch’i-hsin lun shu) on the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] was probably written between 823 and 828. Although [[Zongmi]] is [[recognized]] as a [[Huayan]] [[patriarch]], he considered the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] [[scripture]] to exemplify the [[highest]] [[teaching]], displacing the [[Huayan]] [[Sūtra]] as the [[supreme]] [[Buddhist]] [[teaching]]. |

[[Meditation]]-manual | [[Meditation]]-manual | ||

| − | Around the same time he wrote a major work in eighteen fascicles called A Manual of Procedures for the Cultivation and [[Realization]] of [[Ritual]] Practice according to the [[Scripture]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]]. In this work, [[Zongmi]] discusses the conditions of practice, the methods of worship and the method of seated [[meditation]] ([[zazen]]). | + | Around the same [[time]] he wrote a major work in eighteen fascicles called A Manual of Procedures for the Cultivation and [[Realization]] of [[Ritual]] Practice according to the [[Scripture]] of [[Perfect Enlightenment]]. In this work, [[Zongmi]] discusses the [[conditions]] of practice, the methods of {{Wiki|worship}} and the method of seated [[meditation]] ([[zazen]]). |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

[[Category:Chinese Buddhist Teachers]] | [[Category:Chinese Buddhist Teachers]] | ||

Revision as of 13:45, 17 September 2013

Guifeng Zongmi (圭峰 宗密) (Wade-Giles: Kuei-feng Tsung-mi; Japanese: Keihō Shūmitsu) (780–841) was a Tang dynasty Buddhist scholar-monk, installed as fifth patriarch of the Huayan (Chinese: 華嚴; pinyin: Huáyán; Japanese: Kegon; Sanskrit: Avatamsaka) school as well as a patriarch of the Heze (WG: Ho-tse) lineage of Southern Chan.

Zongmi was deeply affected by both Chan and Huayan. He wrote a number of works on the contemporary situation of Buddhism in Tang China, including critical analyses of Chan and Huayan, as well as numerous scriptural exegeses.

Zongmi was deeply interested in both the practical and doctrinal aspects of Buddhism. He was especially concerned about harmonizing the views of those that tended toward exclusivity in either direction. He provided doctrinal classifications of the Buddhist teachings, accounting for the apparent disparities in the Buddhist doctrines by categorizing them according to their specific aims.

Biography

Early years (780-810)

Zongmi was born in 780 into the powerful and influential Ho family in Hsi-ch’ung County of present-day central Szechwan. In his early years, he studied the Confucian classics, hoping to for a career in the provincial government. When he was seventeen or eighteen, Zongmi lost his father and took up Buddhist studies. In an 811 letter to a friend, he wrote that for three years he

[G]ave up eating meat, examined Buddhist scriptures and treatises, became familiar with the virtues of meditation and sought out the acquaintance of noted monks.

At the age of twenty-two, he returned to the Confucian classics and deepened his understanding, studying at the I-hsüeh yüan Confucian Academy in Sui-chou. His later writings reveal a detailed familiarity with the Confucian Analects, the Classic of Filial Piety ( Xiao Jing), the Classic of Rites as well as historical texts and Taoist classics such as the works of Lao tzu.

Chán (804-810)

At the age of twenty-four, Zongmi met the Chan master Sui-chou Tao-yüan and trained in Zen Buddhism for two or three years. He received Tao-yuan’s seal in 807, the year he was fully ordained as a Buddhist monk.

In his autobiographical summary he states that it was the Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment (Yüan-chüeh ching) which led him to enlightenment, his "mind-ground opened thoroughly [...] It's [the scripture’s] meaning was as clear and bright as the heavens." Zongmi’s sudden awakening after reading only two or three pages of the scripture had a profound impact upon his subsequent scholarly career. He propounded the necessity of scriptural studies in Chan, and was highly critical of what he saw as the antinomianism of the Hung-chou lineage derived from Mazu Daoyi (traditional Chinese: 馬祖道一; simplified Chinese: 马祖道一; pinyin: Mǎzǔ Dàoyī; Wade–Giles : Ma-tsu Tao-yi, 709 CE–788 CE), which practiced "entrusting oneself to act freely according to the nature of one’s feelings". But Zongmi’s Confucian moral values never left him and he spent much of his career attempting to integrate Confucian ethics with Buddhism.

Hua-yan (810-816)

In 810, at the age of thirty, Zongmi met Ling-feng, a disciple of the preeminent Buddhist scholar and Huayan exegete Ch’eng-kuan (738-839). Ling-feng gave Zongmi a copy of Ch’eng-kuan’s commentary and subcommentary on the Huayan Sūtra(Flower Garland Sutra). The two texts were to have a profound impact on Zongmi. He studied these texts and the sūtra with great intensity, declaring later that due to his assiduous efforts, finally "all remaining doubts were completely washed away." In 812 Zongmi travelled to the western capital, Chang’an, where he spent two years studying with Ch’eng-kuan, who was not only the undisputed authority on Huayan, but was also highly knowledgeable in Chan, Tientai, the Vinaya and San-lun.

Mount Chung-nan (816-828)

Zongmi withdrew to Mount Chung-nan, southwest of Chang’an, in 816 and began his writing career, composing an annotated outline of the Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment, and a compilation of passages from four commentaries on the sūtra. For the next three years Zongmi continued his research into Buddhism, reading the entire Buddhist canon, the Tripitaka, and traveling to various temples on Mount Chung-nan. He returned Chang’an in 819 and continued his studies utilizing the extensive libraries of various monasteries in the capital city. In late 819 he completed a commentary (shu) and subcommentary (ch’ao) on the Diamond Sūtra. In early 821 he returned to Ts’ao-t’ang temple beneath Kuei Peak and hence became known as Guifeng Zongmi (WG:Kuei-feng Tsung-mi. In mid-823 he finally finished his own commentary on the text that had led to his first awakening experience, Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment, and the culmination of a vow he had made some fifteen years earlier. For the next five years Zongmi continued writing and studying on Mount Chung-nan as his fame grew.

Capital city (828-835)

He was summoned to the capital in 828 by Emperor Wenzong (r. 826-840) and awarded the purple robe and the honorific title "Great Worthy" (ta-te; bhadanta). The two years he spent in the capital were significant for Zongmi. He was now a nationally honoured Chan master with extensive contacts among the literati of the day. He turned his considerable knowledge and intellect towards writing for a broader audience rather than the technical exegetical works he had produced for a limited readership of Buddhist specialists. His scholarly efforts became directed towards the intellectual issues of the day and much of his subsequent work was produced at the appeals of assorted literati of the day. He began collecting every extant Chan text in circulation with the goal of producing a Chan canon to create a new section of the Buddhist canon. This work is lost but the title, Collection of Expressions of the Zen Chan Source (Ch’an-yuan chu-ch’uan chi,禪源諸詮集) remains.

Last years (835-841)

It was Zongmi’s association with the great and the powerful that led to his downfall in 835 in an event known as the Ganlu Incident. A high official and friend of Zongmi, Li Xun, in connivance with Emperor Wenzong and the general Zheng Zhu, attempted to curb the power of the court eunuchs by massacring them all. The plot failed and Li Xun fled to Mount Chung-nan seeking refuge with Zongmi. Li Xun was quickly captured and executed and Zongmi was arrested and tried for treason. Impressed with Zongmi’s bravery in the face of execution, the powerful eunuch Yu Hongzhi (魚弘志) persuaded fellow powerful eunuch Qiu Shiliang to spare Zongmi.

Nothing is known about Zongmi’s activities after this event. Zongmi died in the zazen posture on February 1, 841 in Chang-an. He was cremated on March 4 at Guifeng temple. Twelve years later he was awarded the posthumous title Samādi-Prajnā Chan Master and his remains were interred in a stupa called Blue Lotus.

Philosophy

Zongmi’s lifelong work was the attempt to incorporate differing and sometimes conflicting value systems into an integrated framework that could bridge not only the differences between Buddhism and the traditional Taoism and Confucianism, but also within Buddhist theory itself.

Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism

Much of Zongmi’s work was concerned with providing a dialogue between the three religions of China: Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism. He saw all three as expedients, functioning within a particular historical context and although he placed Buddhism as revealing the highest truth of the three, this had nothing to do with the level of understanding of the three sages, Confucius, Lao-tzu and Buddha, (who Zongmi saw as equally enlightened) and everything to do with the particular circumstances in which the three lived and taught. As Zongmi said:

Since encouraging the myriad practices, admonishing against evil, and promoting good contribute in common to order, the three teachings should all be followed and practiced. [However] if it be a matter of investigating the myriad phenomena, exhausting principle, realizing the nature, and reaching the original source, then Buddhism alone is the ultimate judgment.

Zongmi’s early training in Confucianism never left him and he tried to create a syncretic framework where Confucian moral principles could be integrated within the Buddhist teachings.

Sudden and Gradual Enlightenment

Zongmi tried to harmonize the different views on the nature of enlightenment. For the Chan tradition, one of the major issues of the day was the distinction between the Northern line, which advocated a "gradual enlightenment" and the Southern line’s "sudden enlightenment".

Coming from the Southern Chan tradition, Zongmi advocated the Southern teachings of sudden enlightenment. But he also saw both as according with the teachings of the Buddha. He wrote:

It is only because of variations in the style of the World Honored One’s exposition of the teachings that there are sudden expositions in accordance with the truth and gradual expositions in accordance with the capacities [of beings]…this does not mean that there is a separate sudden and gradual [[[teaching]]].

Although the sudden teaching reveals the truth directly, and results in a "sudden" understanding that all beings are Buddhas, this does not mean that one attained Buddhahood rightaway. Hence, Zongmi advocated "sudden enlightenment" followed by "gradual cultivation". This gradual cultivation was to eliminate all remaining traces of defilements of the mind, that prevented one from fully integrating one’s intrinsic Buddha-nature into actual behaviour.

To explain this, Zongmi used the metaphor of water and waves found in the Awakening of Faith scripture. The essential tranquil nature of water which reflects all things (intrinsic enlightenment) is disturbed by the winds of ignorance (unenlightenment, delusion). Although the wind may stop suddenly (sudden enlightenment), the disturbing waves subside only gradually (gradual cultivation) until all motion ceases and the water once again reflects its intrinsic nature (Buddhahood). However, whether disturbed by ignorance or not, the fundamental nature of the water (i.e., the mind) never changes.

Classification of teachings

As with many Buddhist scholars of the day, doctrinal classification (p’an chiao) was an integral part of Zongmi’s work. Zongmi’s "systematic classification of Buddhist doctrine is itself a theory of the Buddhist path (mārga)."

He provided a critique of the various practices which reveal not only the nature of Chan in Tang Dynasty, but also Zongmi’s understanding of Buddhist doctrine.

The Buddha's Teachings

Zongmi arranged the Buddha’s teachings into five categories:

The teaching of men and gods,

The teachings of the Hinayana,

The teaching of phenomenal appearances,

The teaching of the negation of intrinsic phenomenal appearances and

The teaching that reveals the true nature (intrinsic enlightenment).

The "true nature" is the tathagatagarbha or Buddha nature, which is emphasised in Chán. In giving this teaching the highest position, Zongmi altered the classification of Fa-yan, who regarded the Hua-yen teachings to be the supreme teachings and established the common denominator of Chan and Huayen teachings within the "One Vehicle" (ekayana).

Chán teachings

Zongmi’s classification also included the various categories of Chan. He distinguished five categories of Chán-practice:

Bon-pu Zen, aimed at improvement of personal well-being

Gedo Zen, following non-Buddhist teachings

Shojo Zen, the Hinayana teachings

Daijo Zen, aimed at kensho

Saijojo Zen, expressing Buddhanature in daily life, using shikantasa

Analysis of Mind

Zongmi saw enlightenment and its opposite, delusion, as ten reciprocal steps that are not so much separate processes, but parallel processes moving in opposite directions.

Zongmi follows the One Vehicle interpretation of the Yogacara analysis of the Eight Consciousnesses that is found in the Lankavatara Sutra and the Treatise on the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana, in describing the phenomenology of the mind.

In Zongmi's vision, the Real Mind is the true nature which is revealed at the moment of awakening. Before this awakening, True Mind is deluded by thoughts and wrong visions. The phenomenal appearance of this true mind is the tathagatagarbha, and it's deluded manifestation is the alaya-vijnana, or citta, the eighth consciousness of Yogacara. From this deluded consciousness springs manas, the grasping consciousness, which is the seventh consciousness. From there springs the cognitive mind (sixth consciousness) and the five sense-consciousnesses.

Criticism of Chán-schools

Zongmi gave critiques on seven Chan schools in his Prolegomenon to the Collection of Expressions of the Zen Source and although he promoted his own Ho-tse school as exemplifying the highest practice, his accounts of the other schools were balanced and unbiased. It is clear from his writings that in many cases he visited the various Chan monasteries he wrote about and took notes of his discussions with teachers and adapts. His work had an enduring influence on the adaptation of Indian Buddhism to the philosophy of traditional Chinese culture. The writings that remain have proved to be an invaluable source for modern scholars of the history of the development of Buddhism in China.

Hung-chou school

Zongmi was critical of Chan sects that seemed to ignore the moral order of traditional Buddhism and Confucianism. For example, while he saw the Northern line as believing "everything as altogether false", Zongmi claimed the Hung-chou tradition, derived from Mazu Daoyi (709-788), believed "everything as altogether true".

According to Zongmi, the Hung-chou school teaching led to a radical nondualism that believed that all actions, good or bad, as expressing essential Buddha-nature, denying the need for spiritual cultivation and moral discipline. This was a dangerously antinomian view as it eliminated all moral distinctions and validated any actions as expressions of the essence of Buddha-nature.

While Zongmi acknowledged that the essence of Buddha-nature and its functioning in the day-to-day reality are but difference aspects of the same reality, he insisted that there is a difference. To avoid the dualism he saw in the Northern Line and the radical nondualism and antinomianism of the Hung-chou school, Zongmi’s paradigm preserved "an ethically critical duality within a larger ontological unity", an ontology which he claimed was lacking in Hung-chou Chan.

Northern Chán

Zongmi’s critique of Northern Chan was based on its practice of removing impurities of the mind to reach enlightenment. Zongmi criticized this on the basis that the Northern school was under the misconception that impurities were "real" as opposed to "empty" (i.e., lack any independent reality of their own) and therefore this was a dualistic teaching. Zongmi, on the other hand, saw impurities of the mind as intrinsically "empty" and naturally removable by the intrinsically pure nature of the mind. This understanding of Zongmi came from the Awakening of Faith scripture which espoused the tathagatagarbha doctrine of the intrinsically enlightened nature possessed by all beings.

Ox-head school

His criticism of another prominent Chan lineage of the time, the Ox-head School, was also based on the tathāgatagarbha doctrine but in this case Zongmi saw their teaching as a one-sided understanding of emptiness. He claimed that the Ox-head School taught "no mind" (i.e., the emptiness of mind) but did not recognize the functioning of the mind, assuming that the intrinsically enlightened nature is likewise "empty" and "that there is nothing to be cognized". Zongmi went on to say, "we know that this teaching merely destroys our attachment to feelings but does not yet reveal the nature that is true and luminous".

Writings

Zongmi's writings were extensive and influential. There is no certainty about the quantity of Zongmi’s writings. Zongmi’s epitaph, written by P’ei Hsiu, (787?-860) listed over ninety fascicles. Tsan-ning’s (919-1001) biography claimed over two hundred.

For modern scholars, Zongmi provides the "most valuable sources on Tang dynasty Zen. There is no other extant source even remotely as informative".

Unfortunately, many of Zongmi’s works are lost, including his Collected Writings on the Source of Ch’an (Ch’an-yüan chu-ch’üan-chi) which would provide modern scholars with an invaluable source to reconstruct Tang Dynasty Chan.

Commentary on the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment

Zongmi's first major work was his commentary and subcommentary on Sūtra of Perfect Enlightenment, completed in 823-824. The subcommentary contains extensive data on the teachings, the ideas and practices on the seven houses of Chan. These data are derived from personal experience and observations. These observations provide excellent sources on Tang Dynasty Chan for modern studies.

Chart of Zen Succession

The Chart of the Master-Disciple Succession of the Chan Gate That Has Transmitted the Mind-Ground in China (Chung-hua ch’uan-hsin-ti ch’an-men shih-tzu ch’eng-his t’u), was written at the request of P’ei Hsiu sometime between 830 and 833. The work clarifies the major Ch’an traditions of the Tang era. It contains detailed critiques of the Northern School, the Ox-head School and the two branches of Southern Chan, the Hung-chou and his own Ho-tse (Heze) lines.

The Prolegomenon

The Prolegomenon to the Collection of Expressions of the Zen Source(also known as the Chan Preface) (Ch’an-yuan chu-ch’uan-chi tu-hsu) was written around 833. It provides a theoretical basis for Zongmi’s vision of the correlation between Chan and the Buddhist scriptures. It gives accounts of the several lineages extant at the time, many of which had died out by the time of the Song Dynasty (960-1279). In this preface, Zongmi says that he had assembled the contemporary Chan practices and teachings into ten categories. Unfortunately, the collection itself is lost, and only the preface exists.

On the Original Nature of Man

Zongmi's Inquiry into the Origin of Humanity, (or On the Original Nature of Man, or The Debate on an Original Person) (原人論 Yüan jen lun) was written sometime between 828 and 835. This essay became one of his best-known works.

It surveys the current major Buddhist teachings of the day, as well as Confucian and Taoist teachings. It not only shows how Buddhism is superior to the native Chinese philosophies, but also presents a hierarchy of the profundity of the Buddhist schools. Zongmi criticizes Confucianism for not having an adequate moral system or explanation of causation. He holds up the Buddhist view of karma as the superior system of moral responsibility.

De Bary writes,

Here Tsung-mi's own spiritual development and his consideration of alternative philosophies are clearly reflected, as is his awareness of the need to defend his new faith against critics upholding Chinese tradition against Buddhism It has been said that Tsung-mi wrote this treatise as an answer to the famous essays On the original Nature of Man (Yuan jen) and On the Tao (Yuan tao) by his contemporary Han Yu (768-824), leader of the Confucian resurgence against Buddhism.

However, his goal was not to wholly denigrate or invalidate the Chinese philosophies, but to integrate them into Buddhist teachings to reach a greater understanding of how the human condition came into being.

The writing style is simple and straightforward, and the content not overly technical, making the work accessible to non-Buddhist intellectuals of the day.

Commentary on the Awakening of Faith

The undated commentary (Ch’i-hsin lun shu) on the Awakening of Faith was probably written between 823 and 828. Although Zongmi is recognized as a Huayan patriarch, he considered the Awakening of Faith scripture to exemplify the highest teaching, displacing the Huayan Sūtra as the supreme Buddhist teaching.

Meditation-manual

Around the same time he wrote a major work in eighteen fascicles called A Manual of Procedures for the Cultivation and Realization of Ritual Practice according to the Scripture of Perfect Enlightenment. In this work, Zongmi discusses the conditions of practice, the methods of worship and the method of seated meditation (zazen).