Difference between revisions of "Huineng"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> '''Dajian Huineng''' (大鑒惠能; Pinyin: Dàjiàn Huìnéng; Japanese: Daikan Enō; Korean: Hyeneung, 638–713) was a Chinese C...") |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File:Huineng02a.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huineng02a.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

<poem> | <poem> | ||

| − | '''Dajian Huineng''' (大鑒惠能; Pinyin: Dàjiàn Huìnéng; Japanese: Daikan Enō; Korean: Hyeneung, 638–713) was a Chinese Chán (Zen) monastic who is one of the most important figures in the entire tradition, according to standard Zen hagiographies. Huineng has been traditionally viewed as the Sixth and Last Patriarch of Chán Buddhism. | + | '''Dajian [[Huineng]]''' (大鑒惠能; Pinyin: Dàjiàn Huìnéng; [[Japanese]]: Daikan Enō; [[Korean]]: Hyeneung, 638–713) was a {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Chán]] ([[Zen]]) [[monastic]] who is one of the most important figures in the entire [[tradition]], according to standard [[Zen]] hagiographies. [[Huineng]] has been [[traditionally]] viewed as the Sixth and Last [[Patriarch]] of [[Chán]] [[Buddhism]]. |

| − | Biography | + | {{Wiki|Biography}} |

| − | Most modern scholars doubt the historicity of traditional biographies and works written about Huineng. The two primary sources for Huineng's life are the preface to the Platform Sutra and the Transmission of the Lamp. | + | Most {{Wiki|modern}} [[scholars]] [[doubt]] the historicity of [[traditional]] {{Wiki|biographies}} and works written about [[Huineng]]. The two [[primary]] sources for Huineng's [[life]] are the preface to the [[Platform Sutra]] and the [[Transmission]] of the [[Lamp]]. |

| − | Huineng was born into the Lu family in 638 A.D. in Xinzhou (present-day Xinxing County) in Guangdong province. His father died when he was young and his family was poor. As a consequence, Huineng had no opportunity to learn to read or write and is said to have remained illiterate his entire life. | + | [[Huineng]] was born into the Lu family in 638 A.D. in Xinzhou (present-day Xinxing County) in Guangdong province. His father [[died]] when he was young and his family was poor. As a consequence, [[Huineng]] had no opportunity to learn to read or write and is said to have remained illiterate his entire [[life]]. |

| − | The Platform Sutra | + | The [[Platform Sutra]] |

| − | The Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch is attributed to Huineng. It was constructed over a longer period of time, and contains different layers of writing. It is... | + | The Platform [[Sūtra]] of the [[Sixth Patriarch]] is attributed to [[Huineng]]. It was [[constructed]] over a longer period of [[time]], and contains different layers of [[writing]]. It is... |

| − | ...a wonderful melange of early Chan teachings, a virtual repository of the entire tradition up to the second half of the eighth century. At the heart of the sermon is the same understanding of the Buddha-nature that we have seen in texts attributed to Bodhidharma and Hongren, including the idea that the fundamental Buddha-nature is only made invisible to ordinary humans by their illusions". | + | ...a wonderful melange of early [[Chan]] teachings, a virtual repository of the entire [[tradition]] up to the second half of the eighth century. At the [[heart]] of the {{Wiki|sermon}} is the same [[understanding]] of the [[Buddha-nature]] that we have seen in texts attributed to [[Bodhidharma]] and Hongren, including the [[idea]] that the fundamental [[Buddha-nature]] is only made {{Wiki|invisible}} to ordinary [[humans]] by their [[illusions]]". |

[[File:Huineng Cut Bamboo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huineng Cut Bamboo.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Citation of Buddhist Scriptures | + | Citation of [[Buddhist Scriptures]] |

| − | The Platform Sūtra cites and explains a wide range of Buddhist scriptures: the Diamond Sūtra, the Lotus Sūtra (Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra), the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana-sutra, and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra. | + | The Platform [[Sūtra]] cites and explains a wide range of [[Buddhist scriptures]]: the [[Diamond Sūtra]], the [[Lotus Sūtra]] ([[Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra]]), the [[Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra]], the [[Śūraṅgama Sūtra]], the Laṅkāvatāra [[Sūtra]], the [[Awakening]] of [[Faith]] in the Mahayana-sutra, and the [[Mahaparinirvana Sutra]]. |

| − | Diamond Sutra | + | [[Diamond Sutra]] |

| − | According to the Platform Sutra, one day while delivering firewood to a store, he heard a customer reciting the Diamond Sutra and had an awakening. He immediately inquired about the sutra, and decided to seek out the Fifth Patriarch Hongren at his monastery on Huang Mei Mountain. Some later versions of the story have the customer giving him 10 or 100 taels of silver to provide for his aged mother. After travelling for thirty days on foot, he arrived at Huang Mei Mountain where the Fifth Patriarch was presiding. | + | According to the [[Platform Sutra]], one day while delivering firewood to a [[store]], he [[heard]] a customer reciting the [[Diamond Sutra]] and had an [[awakening]]. He immediately inquired about the [[sutra]], and decided to seek out the [[Fifth Patriarch]] Hongren at his [[monastery]] on Huang Mei Mountain. Some later versions of the story have the customer giving him 10 or 100 taels of silver to provide for his aged mother. After travelling for thirty days on foot, he arrived at Huang Mei Mountain where the [[Fifth Patriarch]] was presiding. |

Introduction to Hongren | Introduction to Hongren | ||

[[File:Huineng25.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huineng25.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | The first chapter of the Ming canon version of the Platform Sutra describes the introduction of Hui-neng to Hongren as follows; | + | The first chapter of the Ming [[canon]] version of the [[Platform Sutra]] describes the introduction of Hui-neng to Hongren as follows; |

| − | The Patriarch asked me, "Who are you and what do you seek?" | + | The [[Patriarch]] asked me, "Who are you and what do you seek?" |

| − | I replied, "Your disciple is a commoner from Xinzhou of Lingnan. I have travelled far to pay homage to you and seek nothing other than Buddhahood." | + | I replied, "Your [[disciple]] is a commoner from Xinzhou of Lingnan. I have travelled far to pay homage to you and seek [[nothing]] other than [[Buddhahood]]." |

| − | "So you're from Lingnan, and a barbarian! How can you expect to become a Buddha?" asked the Patriarch. | + | "So you're from Lingnan, and a barbarian! How can you expect to become a [[Buddha]]?" asked the [[Patriarch]]. |

| − | I replied, "Although people exist as northerners and southerners, in the Buddha-nature there is neither north nor south. A barbarian differs from Your Holiness physically, but what difference is there in our Buddha-nature? | + | I replied, "Although [[people]] [[exist]] as northerners and southerners, in the [[Buddha-nature]] there is neither {{Wiki|north}} nor {{Wiki|south}}. A barbarian differs from Your Holiness {{Wiki|physically}}, but what [[difference]] is there in our [[Buddha-nature]]? |

| − | Hui-neng became a labourer in the monastery, doing chores in the rice mill, chopping wood and pounding rice at the monastery for the next eight months. | + | Hui-neng became a labourer in the [[monastery]], doing chores in the {{Wiki|rice}} mill, chopping wood and pounding {{Wiki|rice}} at the [[monastery]] for the next eight months. |

Succession of Hongren | Succession of Hongren | ||

| − | The Platform Sutra contains the well-known story of the contest for the succession of Hongren. According to the text, Huineng won this contest, but had to flee the monastery to avoid the rage of the supporters of Shenxui. The story is not a factual account, but an 8th-century construction, probably by the so-called Oxhead School. | + | The [[Platform Sutra]] contains the well-known story of the contest for the succession of Hongren. According to the text, [[Huineng]] won this contest, but had to flee the [[monastery]] to avoid the [[rage]] of the supporters of Shenxui. The story is not a {{Wiki|factual}} account, but an 8th-century construction, probably by the so-called Oxhead School. |

| − | Becoming the Sixth Patriarch | + | Becoming the [[Sixth Patriarch]] |

| − | The first chapter of the Platform Sutra tells the well-known apocryphal story of the Dharma-tramsmission from Hongren to Hui-neng. Hongren asked his students to... | + | The first chapter of the [[Platform Sutra]] tells the well-known {{Wiki|apocryphal}} story of the Dharma-tramsmission from Hongren to Hui-neng. Hongren asked his students to... |

[[File:Huineng30635.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huineng30635.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | ... write me a stanza (gatha) [...] He who understands what the Essence of Mind is will be given the robe (the insignia of the Patriarchate) and the Dharma (the ultimate teaching of the Chán school), and I shall make him the Sixth Patriarch. | + | ... write me a [[stanza]] ([[gatha]]) [...] He who [[understands]] what the [[Essence of Mind]] is will be given the robe (the insignia of the Patriarchate) and the [[Dharma]] (the [[ultimate]] [[teaching]] of the [[Chán]] school), and I shall make him the [[Sixth Patriarch]]. |

| − | Only Shenxiu wrote a poem, anonymously on the wall in the middle of the night. It stated: | + | Only [[Shenxiu]] wrote a poem, anonymously on the wall in the middle of the night. It stated: |

| − | 身是菩提樹, The body is a Bodhi tree, | + | 身是菩提樹, The [[body]] is a [[Bodhi tree]], |

| − | 心如明鏡臺。 The mind a standing mirror bright. | + | 心如明鏡臺。 The [[mind]] a [[standing]] [[mirror]] bright. |

| − | 時時勤拂拭, At all times polish it diligently, | + | 時時勤拂拭, At all times {{Wiki|polish}} it diligently, |

勿使惹塵埃。 And let no dust alight. | 勿使惹塵埃。 And let no dust alight. | ||

| − | After having read this poem aloud to him, Hui-neng asked an officer to write another gatha on the wall for him, next to Shenxiu's, which stated: | + | After having read this poem aloud to him, Hui-neng asked an officer to write another [[gatha]] on the wall for him, next to Shenxiu's, which stated: |

| − | + | 菩提本無樹, [[Bodhi]] is fundamentally without any [[tree]]; | |

| − | 明鏡亦非臺。 The bright mirror is also not a stand. | + | 明鏡亦非臺。 The bright [[mirror]] is also not a stand. |

本來無一物, Fundamentally there is not a single thing — | 本來無一物, Fundamentally there is not a single thing — | ||

何處惹塵埃。 Where could any dust be attracted? | 何處惹塵埃。 Where could any dust be attracted? | ||

[[File:Huineng14.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Huineng14.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Hongren read the stanza, and received Huineng in his abode, where he expounded the Diamond Sutra to him. When he came to the passage, "to use the mind yet be free from any attachment," Huineng came to great awakening. He exclaimed, | + | Hongren read the [[stanza]], and received [[Huineng]] in his [[abode]], where he expounded the [[Diamond Sutra]] to him. When he came to the passage, "to use the [[mind]] yet be free from any [[attachment]]," [[Huineng]] came to great [[awakening]]. He exclaimed, |

| − | How amazing that the self nature is originally pure! How amazing that the self nature is unborn and undying! How amazing that the self nature is inherently complete! How amazing that the self nature neither moves nor stays! How amazing that all dharmas come from this self nature! | + | How amazing that the [[self]] nature is originally [[pure]]! How amazing that the [[self]] nature is {{Wiki|unborn}} and undying! How amazing that the [[self]] nature is inherently complete! How amazing that the [[self]] nature neither moves nor stays! How amazing that all [[dharmas]] come from this [[self]] nature! |

| − | Hongren then passed the robe and begging bowl as a symbol of the Dharma Seal of Sudden Enlightenment to Huineng. | + | Hongren then passed the robe and [[begging bowl]] as a [[symbol]] of the [[Dharma Seal]] of [[Sudden Enlightenment]] to [[Huineng]]. |

Interpretation of the verses | Interpretation of the verses | ||

| − | According to the traditional interpretation, which is based on Guifeng Zongmi, the fifth-generation successor of Shenhui, the two verses represent respectively the gradual and the sudden approach. According to McRae, this is an incorrect understanding: | + | According to the [[traditional]] interpretation, which is based on [[Guifeng Zongmi]], the fifth-generation successor of Shenhui, the two verses represent respectively the gradual and the sudden approach. According to McRae, this is an incorrect [[understanding]]: |

| − | [T]he verse attributed to Shenxiu does not in fact refer to gradual or progressive endeavor, but to a constant practice of cleaning the mirror [...] [H]is basic message was that of the constant and perfect teaching, the endless personal manifestation of the bodhisattva ideal. | + | [T]he verse attributed to [[Shenxiu]] does not in fact refer to gradual or progressive endeavor, but to a [[constant practice]] of cleaning the [[mirror]] [...] [H]is basic message was that of the [[constant]] and perfect [[teaching]], the [[endless]] personal [[manifestation]] of the [[bodhisattva ideal]]. |

| − | Huineng's verse does not stand alone, but forms a pair with Shenxiu's verse: | + | Huineng's verse does not stand alone, but [[forms]] a pair with Shenxiu's verse: |

| − | Huineng's verse(s) apply the rhetoric of emptiness to undercut the substantiality of the terms of that formulation. However, the basic meaning of the first proposition still remains". | + | Huineng's verse(s) apply the [[rhetoric]] of [[emptiness]] to undercut the substantiality of the terms of that formulation. However, the basic [[meaning]] of the first proposition still {{Wiki|remains}}". |

| − | McRae notes a similarity in reasoning with the Oxhead School, which used a threefold structure of "absolute, relative and middle", or "thesis-antithesis-synthesis". According to McRae, the Platform Sutra itself is the synthesis in this threefold structure, giving a balance between the need of constant practice and the insight into the absolute. | + | McRae notes a similarity in {{Wiki|reasoning}} with the Oxhead School, which used a threefold structure of "[[absolute]], [[relative]] and middle", or "thesis-antithesis-synthesis". According to McRae, the [[Platform Sutra]] itself is the synthesis in this threefold structure, giving a [[balance]] between the need of [[constant practice]] and the [[insight]] into the [[absolute]]. |

Teachings | Teachings | ||

| − | Sudden Enlightenment | + | [[Sudden Enlightenment]] |

| − | Doctrinally the Southern School is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is sudden, while the Northern School is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is gradual. This was a polemical exaggeration, since both schools were derived from the same tradition, and the so-called Southern School incorporated many teachings of the more influential Northern School.] Eventually both schools died out, but the influence of Shenhui was so immense that all later Chan schools traced their origin to Huineng, and "sudden enlightenment" became a standard doctrine of Chan. | + | Doctrinally the Southern School is associated with the [[teaching]] that [[enlightenment]] is sudden, while the [[Northern School]] is associated with the [[teaching]] that [[enlightenment]] is gradual. This was a polemical {{Wiki|exaggeration}}, since both schools were derived from the same [[tradition]], and the so-called Southern School incorporated many teachings of the more influential [[Northern School]].] Eventually both schools [[died]] out, but the [[influence]] of Shenhui was so immense that all later [[Chan]] schools traced their origin to [[Huineng]], and "[[sudden enlightenment]]" became a standard [[doctrine]] of [[Chan]]. |

| − | No-thought and meditation | + | No-thought and [[meditation]] |

| − | According to tradition Hui-neng taught "no-thought", the "pure and unattached mind" which "comes and goes freely and functions fluently without any hindrance". The alleged Northern schools emphasis on quiet contemplation was criticised by Hui-neng: | + | According to [[tradition]] Hui-neng taught "no-thought", the "[[pure]] and unattached [[mind]]" which "comes and goes freely and functions fluently without any [[hindrance]]". The alleged Northern schools emphasis on quiet [[contemplation]] was criticised by Hui-neng: |

When alive, one keeps sitting without lying down. | When alive, one keeps sitting without lying down. | ||

| − | When dead, one lies without sitting up. | + | When [[dead]], one lies without sitting up. |

In both cases, a set of stinking bones! | In both cases, a set of stinking bones! | ||

| − | What has it to do with the great lesson of life? | + | What has it to do with the great lesson of [[life]]? |

Historical impact | Historical impact | ||

| − | According to modern historiography, Huineng was a marginal and obscure historical figure. Modern scholarship has questioned this hagiography. Historic research reveals that this story was created around the middle of the 8th century, beginning in 731 by Shenhui, a successor to Huineng, to win influence at the Imperial Court. He claimed Huineng to be successor to Hongren, instead of the then publicly recognized successor Shenxiu: | + | According to {{Wiki|modern}} historiography, [[Huineng]] was a marginal and obscure historical figure. {{Wiki|Modern}} {{Wiki|scholarship}} has questioned this hagiography. Historic research reveals that this story was created around the middle of the 8th century, beginning in 731 by Shenhui, a successor to [[Huineng]], to win [[influence]] at the Imperial Court. He claimed [[Huineng]] to be successor to Hongren, instead of the then publicly [[recognized]] successor [[Shenxiu]]: |

| − | It was through the propaganda of Shen-hui (684-758) that Hui-neng (d. 710) became the also today still towering figure of sixth patriarch of Ch’an/Zen Buddhism, and accepted as the ancestor or founder of all subsequent Ch’an lineages . . using the life of Confucius as a template for its structure, Shen-hui invented a hagiography for the then highly obscure Hui-neng. At the same time, Shen-hui forged a lineage of patriarchs of Ch’an back to the Buddha using ideas from Indian Buddhism and Chinese ancestor worship. | + | It was through the [[propaganda]] of Shen-hui (684-758) that Hui-neng (d. 710) became the also today still towering figure of [[sixth patriarch]] of Ch’an/Zen [[Buddhism]], and accepted as the {{Wiki|ancestor}} or founder of all subsequent [[Ch’an]] [[lineages]] . . using the [[life]] of {{Wiki|Confucius}} as a template for its structure, Shen-hui invented a hagiography for the then highly obscure Hui-neng. At the same [[time]], Shen-hui forged a [[lineage]] of [[patriarchs]] of [[Ch’an]] back to the [[Buddha]] using [[ideas]] from [[Indian Buddhism]] and {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|ancestor}} {{Wiki|worship}}. |

| − | In 745 Shenhui was invited to take up residence in the Heze temple in Luoyang. In 753 he fell out of grace, and had to leave the capital to go into exile. The most prominent of the successors of his lineage was Guifeng Zongmi According to Zongmi, Shenhui's approach was officially sanctioned in 796, when "an imperial commission determined that the Southern line of Ch'an represented the orthodox transmission and established Shen-hui as the seventh patriarch, placing an inscription to that effect in the Shen-lung temple". | + | In 745 Shenhui was invited to take up residence in the Heze [[temple]] in Luoyang. In 753 he fell out of grace, and had to leave the {{Wiki|capital}} to go into exile. The most prominent of the successors of his [[lineage]] was [[Guifeng Zongmi]] According to [[Zongmi]], Shenhui's approach was officially sanctioned in 796, when "an imperial commission determined that the Southern line of [[Ch'an]] represented the {{Wiki|orthodox}} [[transmission]] and established Shen-hui as the seventh [[patriarch]], placing an inscription to that effect in the Shen-lung [[temple]]". |

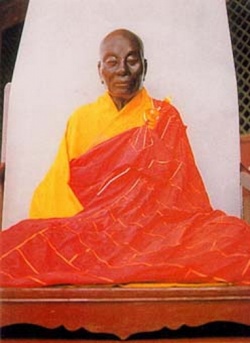

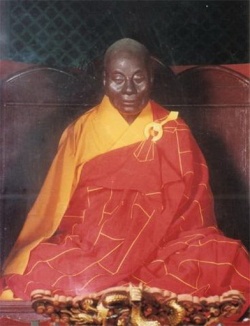

Mummification | Mummification | ||

| − | The mummified body of Huineng is kept in Nanhua Temple in Shaoguan Prefecture (northern Guangdong). | + | The mummified [[body]] of [[Huineng]] is kept in [[Nanhua Temple]] in Shaoguan Prefecture (northern Guangdong). |

| − | Huineng's body was seen by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci who visited Nanhua Temple in 1589. Ricci told the European readers the story of Huineng (in a somewhat edited form), describing him as akin to a Christian ascetic. Ricci names him Lusu (i.e. 六祖, "The Sixth Patriarch"). | + | Huineng's [[body]] was seen by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci who visited [[Nanhua Temple]] in 1589. Ricci told the European readers the story of [[Huineng]] (in a somewhat edited [[form]]), describing him as akin to a {{Wiki|Christian}} [[ascetic]]. Ricci names him Lusu (i.e. 六祖, "The [[Sixth Patriarch]]"). |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{W}} | {{W}} | ||

[[Category:Huineng]] | [[Category:Huineng]] | ||

Revision as of 13:49, 17 September 2013

Dajian Huineng (大鑒惠能; Pinyin: Dàjiàn Huìnéng; Japanese: Daikan Enō; Korean: Hyeneung, 638–713) was a Chinese Chán (Zen) monastic who is one of the most important figures in the entire tradition, according to standard Zen hagiographies. Huineng has been traditionally viewed as the Sixth and Last Patriarch of Chán Buddhism.

Biography

Most modern scholars doubt the historicity of traditional biographies and works written about Huineng. The two primary sources for Huineng's life are the preface to the Platform Sutra and the Transmission of the Lamp.

Huineng was born into the Lu family in 638 A.D. in Xinzhou (present-day Xinxing County) in Guangdong province. His father died when he was young and his family was poor. As a consequence, Huineng had no opportunity to learn to read or write and is said to have remained illiterate his entire life.

The Platform Sutra

The Platform Sūtra of the Sixth Patriarch is attributed to Huineng. It was constructed over a longer period of time, and contains different layers of writing. It is...

...a wonderful melange of early Chan teachings, a virtual repository of the entire tradition up to the second half of the eighth century. At the heart of the sermon is the same understanding of the Buddha-nature that we have seen in texts attributed to Bodhidharma and Hongren, including the idea that the fundamental Buddha-nature is only made invisible to ordinary humans by their illusions".

Citation of Buddhist Scriptures

The Platform Sūtra cites and explains a wide range of Buddhist scriptures: the Diamond Sūtra, the Lotus Sūtra (Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra), the Vimalakīrti Nirdeśa Sūtra, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra, the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, the Awakening of Faith in the Mahayana-sutra, and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra.

Diamond Sutra

According to the Platform Sutra, one day while delivering firewood to a store, he heard a customer reciting the Diamond Sutra and had an awakening. He immediately inquired about the sutra, and decided to seek out the Fifth Patriarch Hongren at his monastery on Huang Mei Mountain. Some later versions of the story have the customer giving him 10 or 100 taels of silver to provide for his aged mother. After travelling for thirty days on foot, he arrived at Huang Mei Mountain where the Fifth Patriarch was presiding.

Introduction to Hongren

The first chapter of the Ming canon version of the Platform Sutra describes the introduction of Hui-neng to Hongren as follows;

The Patriarch asked me, "Who are you and what do you seek?"

I replied, "Your disciple is a commoner from Xinzhou of Lingnan. I have travelled far to pay homage to you and seek nothing other than Buddhahood."

"So you're from Lingnan, and a barbarian! How can you expect to become a Buddha?" asked the Patriarch.

I replied, "Although people exist as northerners and southerners, in the Buddha-nature there is neither north nor south. A barbarian differs from Your Holiness physically, but what difference is there in our Buddha-nature?

Hui-neng became a labourer in the monastery, doing chores in the rice mill, chopping wood and pounding rice at the monastery for the next eight months.

Succession of Hongren

The Platform Sutra contains the well-known story of the contest for the succession of Hongren. According to the text, Huineng won this contest, but had to flee the monastery to avoid the rage of the supporters of Shenxui. The story is not a factual account, but an 8th-century construction, probably by the so-called Oxhead School.

Becoming the Sixth Patriarch

The first chapter of the Platform Sutra tells the well-known apocryphal story of the Dharma-tramsmission from Hongren to Hui-neng. Hongren asked his students to...

... write me a stanza (gatha) [...] He who understands what the Essence of Mind is will be given the robe (the insignia of the Patriarchate) and the Dharma (the ultimate teaching of the Chán school), and I shall make him the Sixth Patriarch.

Only Shenxiu wrote a poem, anonymously on the wall in the middle of the night. It stated:

身是菩提樹, The body is a Bodhi tree,

心如明鏡臺。 The mind a standing mirror bright.

時時勤拂拭, At all times polish it diligently,

勿使惹塵埃。 And let no dust alight.

After having read this poem aloud to him, Hui-neng asked an officer to write another gatha on the wall for him, next to Shenxiu's, which stated:

菩提本無樹, Bodhi is fundamentally without any tree;

明鏡亦非臺。 The bright mirror is also not a stand.

本來無一物, Fundamentally there is not a single thing —

何處惹塵埃。 Where could any dust be attracted?

Hongren read the stanza, and received Huineng in his abode, where he expounded the Diamond Sutra to him. When he came to the passage, "to use the mind yet be free from any attachment," Huineng came to great awakening. He exclaimed,

How amazing that the self nature is originally pure! How amazing that the self nature is unborn and undying! How amazing that the self nature is inherently complete! How amazing that the self nature neither moves nor stays! How amazing that all dharmas come from this self nature!

Hongren then passed the robe and begging bowl as a symbol of the Dharma Seal of Sudden Enlightenment to Huineng.

Interpretation of the verses

According to the traditional interpretation, which is based on Guifeng Zongmi, the fifth-generation successor of Shenhui, the two verses represent respectively the gradual and the sudden approach. According to McRae, this is an incorrect understanding:

[T]he verse attributed to Shenxiu does not in fact refer to gradual or progressive endeavor, but to a constant practice of cleaning the mirror [...] [H]is basic message was that of the constant and perfect teaching, the endless personal manifestation of the bodhisattva ideal.

Huineng's verse does not stand alone, but forms a pair with Shenxiu's verse:

Huineng's verse(s) apply the rhetoric of emptiness to undercut the substantiality of the terms of that formulation. However, the basic meaning of the first proposition still remains".

McRae notes a similarity in reasoning with the Oxhead School, which used a threefold structure of "absolute, relative and middle", or "thesis-antithesis-synthesis". According to McRae, the Platform Sutra itself is the synthesis in this threefold structure, giving a balance between the need of constant practice and the insight into the absolute.

Teachings

Sudden Enlightenment

Doctrinally the Southern School is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is sudden, while the Northern School is associated with the teaching that enlightenment is gradual. This was a polemical exaggeration, since both schools were derived from the same tradition, and the so-called Southern School incorporated many teachings of the more influential Northern School.] Eventually both schools died out, but the influence of Shenhui was so immense that all later Chan schools traced their origin to Huineng, and "sudden enlightenment" became a standard doctrine of Chan.

No-thought and meditation

According to tradition Hui-neng taught "no-thought", the "pure and unattached mind" which "comes and goes freely and functions fluently without any hindrance". The alleged Northern schools emphasis on quiet contemplation was criticised by Hui-neng:

When alive, one keeps sitting without lying down.

When dead, one lies without sitting up.

In both cases, a set of stinking bones!

What has it to do with the great lesson of life?

Historical impact

According to modern historiography, Huineng was a marginal and obscure historical figure. Modern scholarship has questioned this hagiography. Historic research reveals that this story was created around the middle of the 8th century, beginning in 731 by Shenhui, a successor to Huineng, to win influence at the Imperial Court. He claimed Huineng to be successor to Hongren, instead of the then publicly recognized successor Shenxiu:

It was through the propaganda of Shen-hui (684-758) that Hui-neng (d. 710) became the also today still towering figure of sixth patriarch of Ch’an/Zen Buddhism, and accepted as the ancestor or founder of all subsequent Ch’an lineages . . using the life of Confucius as a template for its structure, Shen-hui invented a hagiography for the then highly obscure Hui-neng. At the same time, Shen-hui forged a lineage of patriarchs of Ch’an back to the Buddha using ideas from Indian Buddhism and Chinese ancestor worship.

In 745 Shenhui was invited to take up residence in the Heze temple in Luoyang. In 753 he fell out of grace, and had to leave the capital to go into exile. The most prominent of the successors of his lineage was Guifeng Zongmi According to Zongmi, Shenhui's approach was officially sanctioned in 796, when "an imperial commission determined that the Southern line of Ch'an represented the orthodox transmission and established Shen-hui as the seventh patriarch, placing an inscription to that effect in the Shen-lung temple".

Mummification

The mummified body of Huineng is kept in Nanhua Temple in Shaoguan Prefecture (northern Guangdong).

Huineng's body was seen by the Jesuit Matteo Ricci who visited Nanhua Temple in 1589. Ricci told the European readers the story of Huineng (in a somewhat edited form), describing him as akin to a Christian ascetic. Ricci names him Lusu (i.e. 六祖, "The Sixth Patriarch").