Difference between revisions of "Mogao Caves In China"

(Created page with "thumb|250px| <poem> Mogao Grottoes thumb|250px| A {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} inscription records that the first {{Wiki|cave}} in ...") |

|||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

[[Mogao]] Grottoes | [[Mogao]] Grottoes | ||

[[File:Dun -art-1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dun -art-1.jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | A {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} inscription records that the first {{Wiki|cave}} in the [[Mogao]] | + | A {{Wiki|Tang Dynasty}} inscription records that the first {{Wiki|cave}} in the [[Mogao Grottoes]] was made in 366 A.D. The United Nations Educational, [[Scientific]] and {{Wiki|Cultural}} Organization ({{Wiki|UNESCO}}) listed the[[ Mogao Grottoes]] on the [[World]] Heritage List in 1987. According to {{Wiki|archaeologists}}, it is the greatest and most consummate repository of [[Buddhist art]] in the [[world]]. |

[[File:Dunh .jpg|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dunh .jpg|thumb|250px|]] | ||

Despite erosion and man-made destruction, the 492 [[caves]] are well preserved, with frescoes covering an area of 45,000 square metres, more than 2,000 colored sculptured figures and five wooden eaves overhanging the [[caves]]. | Despite erosion and man-made destruction, the 492 [[caves]] are well preserved, with frescoes covering an area of 45,000 square metres, more than 2,000 colored sculptured figures and five wooden eaves overhanging the [[caves]]. | ||

[[File:Dunh 5.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | [[File:Dunh 5.JPG|thumb|250px|]] | ||

| − | Many pavilions, towers, [[temples]], [[pagodas]], {{Wiki|palaces}}, courtyards, towns and [[bridges]] in the murals provide valuable materials for the study of | + | Many pavilions, towers, [[temples]], [[pagodas]], {{Wiki|palaces}}, courtyards, towns and [[bridges]] in the murals provide valuable materials for the study of [[Chinese architecture]]. Other paintings depict {{Wiki|Chinese}} and foreign musical performances, [[dancing]] and acrobatics. |

| − | The '{{Wiki|Cave}} for Preserving [[Scriptures]]', was discovered by a | + | The '{{Wiki|Cave}} for Preserving [[Scriptures]]', was discovered by a [[Wikipedia:Taoism|Taoist]] [[monk]] {{Wiki|Wang Yuanlu}} in 1900. The {{Wiki|cave}} contains more than 50,000 [[sutras]], documents and paintings covering a period from the 4th to the 11th centuries. It was one of China's most significant {{Wiki|archaeological}} finds. These [[precious]] [[relics]] are of great historical and [[scientific]] value. |

| − | + | [[Dunhuang]] and the {{Wiki|Cave}} of Manuscripts | |

| − | + | [[Dunhuang]] has 492 [[caves]], with 45,000 square meters of frescos, 2, 415 painted [[statues]] and five wooden-structured [[caves]]. The [[Mogao Grottoes]] contain priceless paintings, sculptures, some 50,000 [[Buddhist scriptures]], historical documents, textiles, and other [[relics]] that first stunned the [[world]] in the early 1900s. | |

| − | The [[Mogao Caves]], or [[Mogao]] | + | The [[Mogao Caves]], or [[Mogao Grottoes]] (also known as the [[Caves of the Thousand Buddhas and Dunhuang Caves]]) [[form]] a system of 492 [[temples]] 25 km (15.5 {{Wiki|miles}}) {{Wiki|southeast}} of the center of [[Dunhuang]], an oasis strategically located at a [[religious]] and {{Wiki|cultural}} crossroads on the [[Silk Road]], in [[Wikipedia:Gansu|Gansu province]], [[China]]. The [[caves]] contain some of the finest examples of [[Buddhist art]] spanning a period of 1,000 years. Construction of the [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|cave}} [[shrines]] began in 366 AD as places to [[store]] [[scriptures]] and [[art]]. The [[Mogao Caves]] are the best known of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} [[Buddhist grottoes]] and, along with [[Longmen Grottoes]] and [[Yungang Grottoes]], are one of the three famous {{Wiki|ancient}} sculptural sites of [[China]] |

| − | According to local legend, in 366 AD a [[Buddhist monk]], Le Zun , had a [[vision]] of a thousand [[Buddhas]] and inspired the excavation of the [[caves]] he envisioned. The number of [[temples]] eventually grew to more than a thousand. As [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] valued austerity in [[life]], they sought [[retreat]] in remote [[caves]] to further their quest for [[enlightenment]]. From the 4th until the 14th century, [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] at | + | According to local legend, in 366 AD a [[Buddhist monk]], [[Le Zun]] , had a [[vision]] of a thousand [[Buddhas]] and inspired the excavation of the [[caves]] he envisioned. The number of [[temples]] eventually grew to more than a thousand. As [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] valued austerity in [[life]], they sought [[retreat]] in remote [[caves]] to further their quest for [[enlightenment]]. From the 4th until the 14th century, [[Buddhist]] [[monks]] at [[Dunhuang]] collected [[scriptures]] from the {{Wiki|west}} while many [[pilgrims]] passing through the area painted murals inside the [[caves]]. The {{Wiki|cave}} paintings and architecture served as aids to [[meditation]], as [[visual]] {{Wiki|representations}} of the quest for [[enlightenment]], as mnemonic devices, and as [[teaching]] tools to inform illiterate {{Wiki|Chinese}} about [[Buddhist]] [[beliefs]] and stories. |

The murals cover 450,000 square feet. The [[caves]] were walled off sometime after the 11th century after they had become a repository for [[venerable]], damaged and used manuscripts and [[hallowed]] paraphernalia. | The murals cover 450,000 square feet. The [[caves]] were walled off sometime after the 11th century after they had become a repository for [[venerable]], damaged and used manuscripts and [[hallowed]] paraphernalia. | ||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

Discovery | Discovery | ||

| − | In the early 1900s, a {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|Taoist}} named Wang Yuanlu appointed himself {{Wiki|guardian}} of some of these [[temples]]. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main {{Wiki|cave}}. Behind the wall was a | + | In the early 1900s, a {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|Taoist}} named [[Wang Yuanlu]] appointed himself {{Wiki|guardian}} of some of these [[temples]]. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main {{Wiki|cave}}. Behind the wall was a small {{Wiki|cave}} stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 AD. These included old hemp paper scrolls in {{Wiki|Chinese}} and many other [[languages]], paintings on hemp, silk or paper, numerous damaged figurines of [[Buddhas]], and other [[Buddhist]] {{Wiki|paraphernalia}}. |

| − | The [[subject]] [[matter]] in the scrolls covers diverse {{Wiki|material}}. Along with the expected [[Buddhist canonical]] works are original commentaries, {{Wiki|apocryphal}} works, workbooks, [[books]] of [[prayers]], {{Wiki|Confucian}} works, {{Wiki|Taoist}} works, Nestorian | + | The [[subject]] [[matter]] in the scrolls covers diverse {{Wiki|material}}. Along with the expected [[Buddhist canonical]] works are original commentaries, {{Wiki|apocryphal}} works, workbooks, [[books]] of [[prayers]], {{Wiki|Confucian}} works, {{Wiki|Taoist}} works, [[Wikipedia:Church of the East|Nestorian Christian]] works, works from the {{Wiki|Chinese}} government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. Wang sold the majority of them to {{Wiki|Aurel Stein}} for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a [[deed]] which made him notorious to this day in the [[minds]] of many {{Wiki|Chinese}}. |

| − | Rumors of this discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910. These included a joint British/Indian group led by | + | Rumors of this discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910. These included a joint British/Indian group led by [[Wikipedia:Marc Aurel Stein|Aurel Stein]] (who took hundreds of copies of the [[Diamond Sutra]] because he was unable to read {{Wiki|Chinese}}), a {{Wiki|French}} expedition under {{Wiki|Paul Pelliot}}, a [[Japanese]] expedition under Otani Kozui which arrived after the {{Wiki|Chinese}} government's forces and a {{Wiki|Russian}} expedition under Sergei F. Oldenburg which found the least. |

| − | Pelloit was [[interested]] in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the [[monastery]] and associated lay men's groups. These manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the [[Buddhist texts]] (the target of the preservation [[effort]]) were written on the {{Wiki|opposite}} side of the paper. The remaining {{Wiki|Chinese}} manuscripts were sent to {{Wiki|Peking}} ({{Wiki|Beijing}}) at the [[order]] of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} government. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the [[temples]], funded in part by solicited {{Wiki|donations}} from neighboring towns and in part by {{Wiki|donations}} from Stein and Pelliot. The {{Wiki|image}} of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|astronomy}} | + | Pelloit was [[interested]] in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the [[monastery]] and associated lay men's groups. These manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the [[Buddhist texts]] (the target of the preservation [[effort]]) were written on the {{Wiki|opposite}} side of the paper. The remaining {{Wiki|Chinese}} manuscripts were sent to {{Wiki|Peking}} ({{Wiki|Beijing}}) at the [[order]] of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} government. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the [[temples]], funded in part by solicited {{Wiki|donations}} from neighboring towns and in part by {{Wiki|donations}} from Stein and Pelliot. The {{Wiki|image}} of the {{Wiki|Chinese}} {{Wiki|astronomy}} [[Dunhuang]] map is one of the many important artifact found on the scrolls. |

Today, the site is the [[subject]] of an ongoing {{Wiki|archaeological}} project. The [[Mogao Caves]] became one of the {{Wiki|UNESCO}} [[World]] Heritage Sites in 1987. | Today, the site is the [[subject]] of an ongoing {{Wiki|archaeological}} project. The [[Mogao Caves]] became one of the {{Wiki|UNESCO}} [[World]] Heritage Sites in 1987. | ||

| Line 41: | Line 41: | ||

The first part of the document consists of a collection of predictions based on shapes of clouds - {{Wiki|evidence}} of the important role [[divination]] played in {{Wiki|ancient}} [[China]]. | The first part of the document consists of a collection of predictions based on shapes of clouds - {{Wiki|evidence}} of the important role [[divination]] played in {{Wiki|ancient}} [[China]]. | ||

| − | Dr Francoise Praderie, from the {{Wiki|Paris}} Observatory, who studied the map with fellow {{Wiki|French}} astronomer Dr Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud, said: "The origin of the star chart's [[manufacture]] and {{Wiki|real}} use {{Wiki|remains}} unknown. One can conjecture that it was used for {{Wiki|military}} and travellers' needs and probably also for uranomancy - [[divination]] by consulting the [[heavens]] - as suggested by the cloud [[divination]] texts preceding the charts. "The long [[tradition]] in [[China]] of searching the sky for [[celestial]] {{Wiki|omens}} has therefore led to an early and [[unsurpassed]] precision in star catalogues." | + | Dr Francoise Praderie, from the {{Wiki|Paris}} Observatory, who studied the map with fellow {{Wiki|French}} astronomer Dr {{Wiki|Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud}}, said: "The origin of the star chart's [[manufacture]] and {{Wiki|real}} use {{Wiki|remains}} unknown. One can conjecture that it was used for {{Wiki|military}} and travellers' needs and probably also for uranomancy - [[divination]] by consulting the [[heavens]] - as suggested by the cloud [[divination]] texts preceding the charts. "The long [[tradition]] in [[China]] of searching the sky for [[celestial]] {{Wiki|omens}} has therefore led to an early and [[unsurpassed]] precision in star catalogues." |

</poem> | </poem> | ||

{{R}} | {{R}} | ||

[http://www.crystalinks.com/chinacaves.html www.crystalinks.com] | [http://www.crystalinks.com/chinacaves.html www.crystalinks.com] | ||

[[Category:Dunhuang]] | [[Category:Dunhuang]] | ||

Revision as of 11:18, 20 September 2013

Mogao Grottoes

A Tang Dynasty inscription records that the first cave in the Mogao Grottoes was made in 366 A.D. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) listed theMogao Grottoes on the World Heritage List in 1987. According to archaeologists, it is the greatest and most consummate repository of Buddhist art in the world.

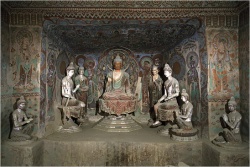

Despite erosion and man-made destruction, the 492 caves are well preserved, with frescoes covering an area of 45,000 square metres, more than 2,000 colored sculptured figures and five wooden eaves overhanging the caves.

Many pavilions, towers, temples, pagodas, palaces, courtyards, towns and bridges in the murals provide valuable materials for the study of Chinese architecture. Other paintings depict Chinese and foreign musical performances, dancing and acrobatics.

The 'Cave for Preserving Scriptures', was discovered by a Taoist monk Wang Yuanlu in 1900. The cave contains more than 50,000 sutras, documents and paintings covering a period from the 4th to the 11th centuries. It was one of China's most significant archaeological finds. These precious relics are of great historical and scientific value.

Dunhuang and the Cave of Manuscripts

Dunhuang has 492 caves, with 45,000 square meters of frescos, 2, 415 painted statues and five wooden-structured caves. The Mogao Grottoes contain priceless paintings, sculptures, some 50,000 Buddhist scriptures, historical documents, textiles, and other relics that first stunned the world in the early 1900s.

The Mogao Caves, or Mogao Grottoes (also known as the Caves of the Thousand Buddhas and Dunhuang Caves) form a system of 492 temples 25 km (15.5 miles) southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis strategically located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu province, China. The caves contain some of the finest examples of Buddhist art spanning a period of 1,000 years. Construction of the Buddhist cave shrines began in 366 AD as places to store scriptures and art. The Mogao Caves are the best known of the Chinese Buddhist grottoes and, along with Longmen Grottoes and Yungang Grottoes, are one of the three famous ancient sculptural sites of China

According to local legend, in 366 AD a Buddhist monk, Le Zun , had a vision of a thousand Buddhas and inspired the excavation of the caves he envisioned. The number of temples eventually grew to more than a thousand. As Buddhist monks valued austerity in life, they sought retreat in remote caves to further their quest for enlightenment. From the 4th until the 14th century, Buddhist monks at Dunhuang collected scriptures from the west while many pilgrims passing through the area painted murals inside the caves. The cave paintings and architecture served as aids to meditation, as visual representations of the quest for enlightenment, as mnemonic devices, and as teaching tools to inform illiterate Chinese about Buddhist beliefs and stories.

The murals cover 450,000 square feet. The caves were walled off sometime after the 11th century after they had become a repository for venerable, damaged and used manuscripts and hallowed paraphernalia.

Discovery

In the early 1900s, a Chinese Taoist named Wang Yuanlu appointed himself guardian of some of these temples. Wang discovered a walled up area behind one side of a corridor leading to a main cave. Behind the wall was a small cave stuffed with an enormous hoard of manuscripts dating from 406 to 1002 AD. These included old hemp paper scrolls in Chinese and many other languages, paintings on hemp, silk or paper, numerous damaged figurines of Buddhas, and other Buddhist paraphernalia.

The subject matter in the scrolls covers diverse material. Along with the expected Buddhist canonical works are original commentaries, apocryphal works, workbooks, books of prayers, Confucian works, Taoist works, Nestorian Christian works, works from the Chinese government, administrative documents, anthologies, glossaries, dictionaries, and calligraphic exercises. Wang sold the majority of them to Aurel Stein for the paltry sum of 220 pounds, a deed which made him notorious to this day in the minds of many Chinese.

Rumors of this discovery brought several European expeditions to the area by 1910. These included a joint British/Indian group led by Aurel Stein (who took hundreds of copies of the Diamond Sutra because he was unable to read Chinese), a French expedition under Paul Pelliot, a Japanese expedition under Otani Kozui which arrived after the Chinese government's forces and a Russian expedition under Sergei F. Oldenburg which found the least.

Pelloit was interested in the more unusual and exotic of Wang's manuscripts such as those dealing with the administration and financing of the monastery and associated lay men's groups. These manuscripts survived only because they formed a type of palimpsest in which the Buddhist texts (the target of the preservation effort) were written on the opposite side of the paper. The remaining Chinese manuscripts were sent to Peking (Beijing) at the order of the Chinese government. Wang embarked on an ambitious refurbishment of the temples, funded in part by solicited donations from neighboring towns and in part by donations from Stein and Pelliot. The image of the Chinese astronomy Dunhuang map is one of the many important artifact found on the scrolls.

Today, the site is the subject of an ongoing archaeological project. The Mogao Caves became one of the UNESCO World Heritage Sites in 1987.

A Chinese star chart possibly dating from the 7th century AD mapped the heavens with an accuracy unsurpassed until the Renaissance, according to research. The Dunhuang chart is the oldest manuscript star map in the world and one of the most valuable treasures in astronomy.

The fine paper scroll, measuring 210 by 25 centimetres, (82 by 10 inches) displays no less than 1,345 stars grouped in 257 non-constellation patterns. Such detail was not matched until Galileo and other European astronomers began searching the skies hundreds of years later - and they had the advantage of telescopes.

The chart includes very faint stars that are extremely difficult to find with the naked eye. It also represents the sky as a sphere projected on a cylinder, a modern technique first adopted in Europe in the 15th century.

The first part of the document consists of a collection of predictions based on shapes of clouds - evidence of the important role divination played in ancient China.

Dr Francoise Praderie, from the Paris Observatory, who studied the map with fellow French astronomer Dr Jean-Marc Bonnet-Bidaud, said: "The origin of the star chart's manufacture and real use remains unknown. One can conjecture that it was used for military and travellers' needs and probably also for uranomancy - divination by consulting the heavens - as suggested by the cloud divination texts preceding the charts. "The long tradition in China of searching the sky for celestial omens has therefore led to an early and unsurpassed precision in star catalogues."