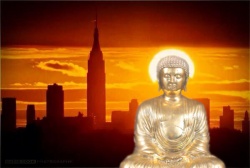

Racial Hierarchy in Modern Buddhism

I would suggest that amongst western Tibetan Buddhists there is a strong borderland complex along with an unspoken racial hierarchy where Tibetan teachers and monks are held in a higher esteem than non-Tibetans. Great spiritual and even supernatural qualities are projected onto various Rinpoches and Lamas, many of which seem to have unofficial propaganda wings which perpetuate such ideas. The exotic Tibetan Lama is seen as holy, a true master of mind, and possessing qualities the western devotee can perhaps strive for yet never really obtain – their own community would likely never recognize them as on par with a Tibetan master even if they did reveal the signs.

Not unlike in former times, part of being in a borderland is making a pilgrimage to a holier land. In ancient Tibet the ideal was to go to India to study and receive empowerments directly from the Indian masters. At the moment with western Tibetan Buddhists one is almost obliged to travel to India or Nepal, or even Tibet itself if you have the opportunity, to study under 'real masters' and get a proper handle on Tibetan, which is the language of canon if not a holy language on par with Sanskrit (I have heard it said in Nepal that you also must know Tibetan in order to become enlightened).

Some practitioners are even compelled to adopt Tibetan dress, values and culinary preferences, which is at times encouraged by Tibetans who denounce the west as materialistic and decadent while proclaiming the good qualities of their own civilization.

In contrast to western Tibetan Buddhism, Theravāda in the west has arguably advanced towards an acclimatized form that is comfortable with itself and visibly less and less dependent on Asian teachers and models. Western or at least Anglo-Theravāda is actually seen as quite legitimate in English speaking Asia, like Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

Ajahn Brahm and Bhikkhu Bodhi, for example, are well regarded figures in their own right in said countries. Ajahn Brahm as an Englishman teaches regularly around Asia. Arguably you do not see much of anything similar in western Tibetan Buddhism – how many eminent western Lamas teach to thousands of Himalayan people on a single day while receiving their devout respect?

One reason why western Tibetan Buddhists are so unwilling to step out of their borderland complex is likely due to their Tibetan teachers who have a vested interest in maintaining a monopoly over their spiritual authority. The reality is that most Tibetan teachers, be they a wealthy Rinpoche or not, are representatives of people in rather dire circumstances in South Asia.

While they as individuals might not have to worry about finances and food, the people under them and their greater communities do in fact depend on them and the income they directly and indirectly bring in.

There are even monks who have escape plans where they tag along with an eminent teacher visiting the west and then disappear (this happens so often that it is increasingly difficult for Tibetan monks, even with Indian or Nepali passports, to get visas to the west and other Asian countries).

How many Tibetan refugees in Nepal and India, for example, make a comfortable livelihood from the foreign devotees who come to attend teachings and visit with eminent teachers? If it were not for their holy teachers, these Tibetan communities would likely be rather destitute and neglected, like the Afghan refugees. The Tibetan clergy in South Asia have a good thing going and cannot afford to lose it, both for themselves and the sake of their people. To delegate real spiritual authority to non-Tibetans would jeopardize religious and associated economic arrangements that their people very deeply depend on. As one friend of mine said, “The Tibetans in India have one export: Buddhism.”

Again, in contrast to other forms of Buddhism, this is not the case. The institutions of Japanese Zen, be it Sōtō or Rinzai, do not stand to lose or gain much by having westerners transplant said traditions in their native countries, which aids in explaining the 'loose reigns' policy the older Japanese traditions (excluding SGI) take with respect to overseas operations. Japanese Buddhist institutions are also wealthy and deeply rooted in their native soil, so there is minimal sense of insecurity on their part. They don't need foreign support and don't try to get it.

In due time perhaps Tibetan Vajrayāna in the west will simply become Vajrayāna, and less importance will be laid upon the ethnic background of teachers and practitioners. This is perhaps comparable to Kabbalah and Jewish Mysticism which, while originally tied to a certain ethnic group, is practiced widely with the ethnic backgrounds of adepts of little relevance.