Tibetan art

Inseparable from the tenets and precepts of Buddhism is a concept of reality that has led some modern observers to consider Buddhism as much a philosophy as a religion. Since Tibetan art, historically, has been entirely and exclusively religious, to that extent it is something of a philosophic art as well. Although much Tibetan art uses figuration, depicting person-like beings and creatures that, however mythological, supramundane, or surreal, are pseudo-realistic and thus recognizable, it differs fundamentally from Western art, specifically from religous art. Western art uses illustration to depict its religious narrative; artists imagined and depicted every being in the biblical story and cosmology, including such mysterious concepts as the holy ghost (often represented through the symbol of a pair of wings, which is nonetheless a recognizable image from our world), such cosmic actors as Lucifer/Satan and the archangel Michael, and even God himself. (Judaism and Islam forbade the use of representational imagery altogether.) But Tibetan Buddhism devised an art that goes beyond illustration, conceiving figures and giving form to beings who have no inherent, intrinsic form and, according to Buddhist teaching, no tangible reality, in order to represent abstract concepts or spiritual attainments or conditions such as compassion or wisdom. Thus Tibetan art, uniquely, is an art that uses figuration and representational images to express abstraction.

Moreover, especially through its use of mandalas, Tibetan art is an integral part of a spiritual practice and process. A Christian may pray to a painted image of Jesus or Mary--an illustration of the divine being--but a Tibetan Buddhist uses the painting itself as a tool to facilitate the attainment of a spiritual state, and even to achieve transformation into the divine being that images such a spiritual condition.

The Buddha taught through dialogue, through probing questions, and reasoned explanation, rather than through dictum. He did not seek of his listeners submission through faith, but rather conviction based on understanding. His enlightenment was a truth he reached through profound understanding of reality, rather than something bestowed by divine revelation. Thus, the essence of this teaching is that one must not merely accept what is handed down by tradition or authority, but rather "see" for oneself what is true. With this emphasis on "seeing" and understanding, rather than on faith and belief, visual art assumes a central importance, in that vision along with mind are the means for such perception.

FEATURES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF TIBETAN ART

Tibetan art is fundamentally abstract, but arrives at this position from an understanding of reality that is totally contrary to traditional Western assumptions. Yet it is not expressionistic: whereas a contemporary Western artist might use visually abstract elements of shape and color in what is an essentially personal code, to convey a personal concept or feeling about life or reality, or the divine or the hereafter, the Buddhist artist does not express personal views or feelings. Instead, a code of conventionalized symbols, legible to all and to which all subscribe, conveys the common understanding. The components of this code include a variety of divine and supernatural beings in their different roles and stations, as well as the manner in which they are depicted.

The Tibetan Pantheon

The historic Buddha, Shakyamuni, made no mention of a divine creator and refused to be drawn into speculation about the subject. As to whether Shakyamuni promulgated rituals of worship, it is the position of Tibetan Buddhists that the tantras (see below), which lay out such rituals, are authoritative Buddhist works, canonically valid as the word of the Buddha. Yet Tibetan Buddhism conceives of a pantheon of gods and divine beings, bewildering in size and complexity, almost too numerous to be counted. This enormous cast of divinities and supramundane beings, of various origins, animate the walls of Buddhist gompas.

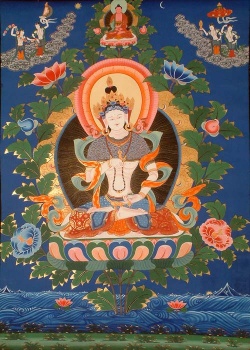

Although Tibetan art portrays human beings, including the historic Buddha Shakyamuni, as well as arhats, spiritual masters, great lamas, and founders of different religious lineages, the preponderance of its images depict supramundane beings. In their main groups, these are: Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, female deities, protectors or tutelary gods (yi-dam), defenders of the faith, guardians of the four cardinal points, and minor deities and supernatural beings. To add further complexity, the leading gods emanate in different forms and appear in various manifestations.

They are depicted in Tibetan art in precise and particular ways, and so numerous are the various deities, and so complex their representations, that the subject may appear daunting. The different manifestations add to the potential confusion, as essentially the same deity is depicted in multiple forms and even in apparently conflicting images. Yet, although only a specialist can make close identifications, the viewer can acquire a general sense of the types of beings depicted in painting or represented in sculpture, and of their nature, role, and significance in the grand cosmic panorama. There is an order--a hierarchy and a system--to this seemingly wild jumble. Therefore, before any survey of the main classifications of Tibetan deities, a few explanations may be helpful.

As they are meant to be understood at the highest level, the Buddhist deities do not exist outside ourselves, but represent aspects of innate human potential--the capacity for compassion, wisdom, mental discipline, and other spiritual conditions and achievements. Having no distinct, independent existence or objective reality, the deities are only symbols of abstract qualities, with no intrinsic worth or value in themselves; they come from one's mind and also from the universal mind. Tibetans do not imagine that they might encounter red or blue beings with four heads and eight arms. Although depicted in Tibetan art as beings in human shape, they are, rather images of spiritual states and conditions, personified.