Tibetan art

Inseparable from the tenets and precepts of Buddhism is a concept of reality that has led some modern observers to consider Buddhism as much a philosophy as a religion. Since Tibetan art, historically, has been entirely and exclusively religious, to that extent it is something of a philosophic art as well. Although much Tibetan art uses figuration, depicting person-like beings and creatures that, however mythological, supramundane, or surreal, are pseudo-realistic and thus recognizable, it differs fundamentally from Western art, specifically from religous art. Western art uses illustration to depict its religious narrative; artists imagined and depicted every being in the biblical story and cosmology, including such mysterious concepts as the holy ghost (often represented through the symbol of a pair of wings, which is nonetheless a recognizable image from our world), such cosmic actors as Lucifer/Satan and the archangel Michael, and even God himself. (Judaism and Islam forbade the use of representational imagery altogether.) But Tibetan Buddhism devised an art that goes beyond illustration, conceiving figures and giving form to beings who have no inherent, intrinsic form and, according to Buddhist teaching, no tangible reality, in order to represent abstract concepts or spiritual attainments or conditions such as compassion or wisdom. Thus Tibetan art, uniquely, is an art that uses figuration and representational images to express abstraction.

Moreover, especially through its use of mandalas, Tibetan art is an integral part of a spiritual practice and process. A Christian may pray to a painted image of Jesus or Mary--an illustration of the divine being--but a Tibetan Buddhist uses the painting itself as a tool to facilitate the attainment of a spiritual state, and even to achieve transformation into the divine being that images such a spiritual condition.

The Buddha taught through dialogue, through probing questions, and reasoned explanation, rather than through dictum. He did not seek of his listeners submission through faith, but rather conviction based on understanding. His enlightenment was a truth he reached through profound understanding of reality, rather than something bestowed by divine revelation. Thus, the essence of this teaching is that one must not merely accept what is handed down by tradition or authority, but rather "see" for oneself what is true. With this emphasis on "seeing" and understanding, rather than on faith and belief, visual art assumes a central importance, in that vision along with mind are the means for such perception.

FEATURES AND CHARACTERISTICS OF TIBETAN ART

Tibetan art is fundamentally abstract, but arrives at this position from an understanding of reality that is totally contrary to traditional Western assumptions. Yet it is not expressionistic: whereas a contemporary Western artist might use visually abstract elements of shape and color in what is an essentially personal code, to convey a personal concept or feeling about life or reality, or the divine or the hereafter, the Buddhist artist does not express personal views or feelings. Instead, a code of conventionalized symbols, legible to all and to which all subscribe, conveys the common understanding. The components of this code include a variety of divine and supernatural beings in their different roles and stations, as well as the manner in which they are depicted.

The Tibetan Pantheon

The historic Buddha, Shakyamuni, made no mention of a divine creator and refused to be drawn into speculation about the subject. As to whether Shakyamuni promulgated rituals of worship, it is the position of Tibetan Buddhists that the tantras (see below), which lay out such rituals, are authoritative Buddhist works, canonically valid as the word of the Buddha. Yet Tibetan Buddhism conceives of a pantheon of gods and divine beings, bewildering in size and complexity, almost too numerous to be counted. This enormous cast of divinities and supramundane beings, of various origins, animate the walls of Buddhist gompas.

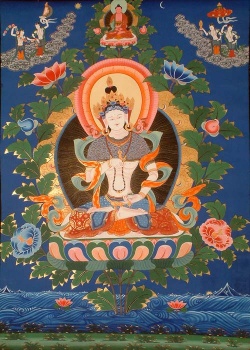

Although Tibetan art portrays human beings, including the historic Buddha Shakyamuni, as well as arhats, spiritual masters, great lamas, and founders of different religious lineages, the preponderance of its images depict supramundane beings. In their main groups, these are: Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, female deities, protectors or tutelary gods (yi-dam), defenders of the faith, guardians of the four cardinal points, and minor deities and supernatural beings. To add further complexity, the leading gods emanate in different forms and appear in various manifestations.

They are depicted in Tibetan art in precise and particular ways, and so numerous are the various deities, and so complex their representations, that the subject may appear daunting. The different manifestations add to the potential confusion, as essentially the same deity is depicted in multiple forms and even in apparently conflicting images. Yet, although only a specialist can make close identifications, the viewer can acquire a general sense of the types of beings depicted in painting or represented in sculpture, and of their nature, role, and significance in the grand cosmic panorama. There is an order--a hierarchy and a system--to this seemingly wild jumble. Therefore, before any survey of the main classifications of Tibetan deities, a few explanations may be helpful.

As they are meant to be understood at the highest level, the Buddhist deities do not exist outside ourselves, but represent aspects of innate human potential--the capacity for compassion, wisdom, mental discipline, and other spiritual conditions and achievements. Having no distinct, independent existence or objective reality, the deities are only symbols of abstract qualities, with no intrinsic worth or value in themselves; they come from one's mind and also from the universal mind. Tibetans do not imagine that they might encounter red or blue beings with four heads and eight arms. Although depicted in Tibetan art as beings in human shape, they are, rather images of spiritual states and conditions, personified.

Identifying poses, symbols, and attributes

Tibetan art uses a sort of visual alphabet or code, whose features help to identify various deities. These features include color, gesture, pose, dress, and the holding of symbolic objects. At the sight of deities who are red, blue, white, yellow, or green, the uninitiated viewer might marvel at what appears to be the artists' freedom in the use of color, but that perception would be inaccurate. Rather, the deities must be depicted according to the appearance proper to them, and with the proper features, each of these elements possessing a symbolic meaning. Thus, among the Dhyani-Buddhas (see below), Ratnasambhava is always yellow, Amoghasiddhi always green. The Manushi-Buddha wears a patched robe and no ornaments, and the great Bodhisattvas are shown in royal dress, bedecked with ornaments.

The supramundane beings seen on gompa walls were not painted there for the sole purpose of decoration, and it is not even accurate to think of them as depicted, however beautifully, as an act of adoration, or as depicted for that purpose, as a Christian artist may create images for the purpose of adoration. Rather, they are vehicles for meditation and transformation, and in creating the image, the artist accumulates merit. In viewing an image and meditating upon it, the believer seeks ultimately to draw that deity into him or herself, to be transformed into the divine being or the spiritual condition it represents, achieving union. In Christian terms, this would be considered heresy.

Symbolic gestures and poses, deriving from the Hindu tradition, are an important part of this visual code. Mudra, for example, are gestures of the hand that represent particular attitudes or actions. In the mudra known as Dharmachakra or turning the Wheel of the Law, the thumb and forefinger of both hands are closed in a circle, with the hands held near the level of the heart: this mudra is appropriate to certain deities and represents preaching. Varada, the mudra symbolizing charity or giving, is shown by a lowered arm, open palm held outward, with all the fingers extended downward, and is appropriate to Ratnasambhava. Asana are symbolic body positions or poses. A well-known example is the Dhyanasana (also known as Vajrasana or Padmasana), the meditation position in which the Buddha Shakyamuni is usually shown--seated, cross-legged, with the soles of the feet visible. There are many other poses, some appropriate to peaceful deities, and others to wrathful ones. An angry deity, for example, is often shown in Alidhasana, standing, with the left leg bent at the knee and the right leg thrust to the side.

Various deities have their appropriate type of throne (a lotus throne, a diamond throne, etc.) and their own particular vahana or mount--animal, bird, or mythic creature. And deities are also depicted holding their own appropriate ritual or symbolic objects. The vajra (dorje in Tibetan) signifies a thunderbolt. This ritual object is not represented as a jagged-edged bolt of lightning, but rather as a small, double-headed scepter, highly stylized. It later developed a parallel signification as the diamond symbol (see below). Among other ritual attributes, a book symbolizes wisdom, a lotus flower is the emblem of purity, a sword is a weapon for destroying ignorance, etc.

Of these, the vajra is the most important of all tantric symbols. It has ancient Indo-European roots--the thunderbolt was wielded by Zeus and by Thor, and similarly appears in Vedic (early Hindu) culture as the weapon of Indra, king of the gods. It also correlates to the lingam of Shiva. As scepter, thunderbolt or phallus, the vajra connotes royalty and is the image of power, the word itself recognized in the names of several deities: one of the three greatest Bodhisattvas is Vajrapani, thunderbolt-in-hand; and Vajradhara (thunderbolt-holder) and Vajrasattva (thunderbolt-being) are names for various forms of the supreme deity. The vajra gradually became linked, conceptually, to a diamond, signifying that which is pure, translucent, indestructible, and adamantine (i.e., the truth of the Buddhist doctrine). As both thunderbolt and diamond, with all their connotations, the power of the symbol is doubled.

In all Vajrayana ritual, the officiant holds a vajra, along with a bell (ghanta). In these rituals, the vajra symbolizes compassion, but it is also explained as symbolizing "means" (often referred to as "skillful means"), for compassion is the means toward achieving enlightenment, and with the dual concept of power and indestructibility inherent in the symbolic vajra object, it represents the invincible power of compassion. The bell signifies wisdom or insight (prajna): the clarity of mind that is able to identify misconceptions, illusions, and falsehood, and discern truth. In Buddhist terms, this means understanding both the impermanence and the emptiness of all things (the void), meaning that phenomena have no independent existence.

Means is the active part of the equation, its action being to remove ignorance and to make wisdom, which was innate and latent, manifest. The vajra, thus representing means, is identified as the male aspect, and the bell, representing wisdom--that which is sought--as the female aspect. (The lotus has also been identified as another emblem of the female aspect or principle, a symbol that reinforces the sexual aspect of this imagery.) Being two, the vajra and the bell represent duality, but they must be used together: wisdom is sought, but without means, is unattainable, and compassion is the means by which wisdom is attained. Enlightenment, which dispels the illusion of duality, depends on both compassion and wisdom, and is attained by the union of these two. Even the shapes of the two ritual objects, thunderbolt-scepter and bell, are symbolically representative and not coincidentally suggestive.

The Artist as Medium

Not only must a Buddha be portrayed in the proper color and dress, with the proper physical marks and appropriate mudra and pose, but must also be depicted exactly in the correct proportions that have been laid down for artists. This is done according to an iconometric diagram that shows the precise span or distance between each physical feature, as, for example, the distance between the eyes, the length of the nose, the width between the ears, etc., down to the smallest details. This is because the Buddha himself was of perfect proportions, and only by exactly reproducing those proportions can the image serve as a spiritual medium. In the process of creating a new painting of the Buddha, on either a wall or a cloth scroll (thangka), an iconometrically correct diagram is first pencilled in. When monks fashion tormas, figurines modeled from tsampa (a dough made of barley flour) and colored butter that are used in important rituals, they consult a pattern book in order to achieve exactitude. Thus there is no range here for an artist's free expression. Reproduction is the aim, not independent expression or creation. If incorrectly drawn or painted, no power attaches to the image, and no transformation can occur.

These strict rules of iconometry govern the figure of a Buddha, but in the depiction of other beings, and in the broader sense, Tibetan art is not concerned with reproduction of the everyday world, but rather with the paradox of depicting that which is not seen. The Tibetan name for the painted scrolls most commonly known as thangkas is mt'on grol, "liberation through sight." Tibetan painting, fundamentally abstract or conceptual, is meant to be used to achieve spiritual transformation. Envisioning a spiritual state, it is thus not concerned with pictorial realism and with such devices as perspective and shading, giving the illusion of volume. To further dispel such illusions of naturalism, the deities are depicted in a plane of uniform light, with no identifiable, external source. The reality portrayed is, instead, transcendental, ultimate.

TANTRIC IMAGES

Peaceful and Wrathful Forms

The image of Buddha (Shakyamuni) known around the world is that of a seated figure in serene meditation--an icon recognized by people who know little else about Buddhism. Yet Tibetan Buddhism depicts deities whose appearance so contradicts the common expectation, that they are immediately misunderstood. The sight of apparently demonic beings dancing on the walls of a sacred temple, alongside the expected images of tranquil deities with gentle faces, both misleads and bewilders uninitiated viewers. As mentioned above, deities may appear in different emanations, in tantric as well as non-tantric form, in which case they are depicted as different beings. The figures of horrific aspect are tantric. Seen within the same gompa, even side by side upon a wall, these contrasting images of serenity and ferocity provide a jolting change of visual rhythm, and an almost emotional dynamism.

These "terrifying deities" apparently derive from several sources. Some, such as Mahakala (see below), were absorbed from Indian Tantrism; others have a native Tibetan origin. According to legend, when Padmasambhava came to Tibet to establish Buddhism, he encountered hostile local gods, whom he vanquished and bound over to serve the new faith. According to various theories, they may have been indigenous gods of the folk religion, or gods from the "old religion," i.e., Bon. Armed and fierce, they guard the entrances to sacred places, combat evil, and show human beings the way to defeat negative emotions that block the way to enlightenment.

Tantric gods are depicted with thick limbs and powerful bodies, their faces contorted and grimacing, eyes glaring, fangs flashing in their open mouths. They brandish sharp weapons and their feet trample the bodies of small beings in human shape. Their figures are cloaked in flame, their hair and eyebrows ablaze. Some wear a crown of skulls, others a necklace of severed human heads. Some drink blood from empty skulls. Tantric deities may have a single head and two arms, but often they have multiple heads and limbs, and some have animal heads. Uninstructed viewers take them to be monsters, and wonder why they are given such prominent place on gompa walls or in thangkas. But the recognition that deities may take such wrathful as well as peaceful forms is fundamental to an understanding of Tibetan iconology and art. It has also been observed that the terrifying deities harness or sublimate the violence that is a reality both of the cosmos and the human personality.

In Buddhist theory, these deities, although given human form (that is, with arms, legs, and faces) are personified visualizations of energy, determination, and invincible will--abstractions depicted through figurative representation. In the same way, the peaceful deities are symbolic representations of compassion, wisdom, and insight.

The concept that a deity may have several emanations or manifestations, a feature common to both Hinduism and Buddhism, is one of the factors that has led to the multiplicity of divinities. Thus Krishna, for example, is an avatar or incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, and the fierce Vajrabhairava is a manifestation of the Buddhist Manjushri, the great Bodhisattva of wisdom. The great Tibetan deities have multiple manifestations, thus adding to the complexity of Tibetan iconography. The relation of a deity to such emanations is sometimes visually represented by placing above the head of the god a smaller head or figure of the deity with which that god is spiritually connected. Thus, a small image of the Dhyani-Buddha Amitabha is often depicted above the head of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Some of the wrathful gods are manifestations of Buddhas and of the great Bodhisattvas, deities who have what might be described as a dual nature or dual capacity. Yet other wrathful beings have a single nature--an independent identity. In either case, the wrathful, ferocious ones bear arms against destructive, negative forces: the passions of anger, hatred, envy, greed, and pride. They are warriors against ignorance, selfishness and the rule of ego. This is the meaning of the weapons they wield: swords to cut through ignorance, axes to hack down anger, and lassos to snare ego. Spiritual and psychological champions, possessed of tireless energy, their ferocious expressions reveal their determination to repel the subtle delusions that ensnare us, hindering human understanding of truth and ultimate reality, obstructing our path to liberation from suffering.

The wrathful deity Trailokya-vijaya deserves special notice here. Although not one of the very commonly depicted deities, he appears repeatedly in the Jampa mandalas (see Jampa gompa, below). He is "the conqueror of the three worlds," a name signifying his victory over the enemies of the three worlds of the manifested universe: the celestial, earthly, and infernal realms. The primary mandala of Jampa has been identified as the Vajrahadatu mandala, whose central deity is Vairocana; however, Trailokya-vijaya is known as an active or wrathful aspect of Vairocana, and as such he appears in several of the Jampa mandalas. (Trailokya-vijaya is referred to in lines 56-59 of the Jampa Inscriptions: see below.) His color is blue and he is generally depicted with two of his hands crossed at his breast in the mudra known as vajrahumkara.

The little figures whom these deities trample beneath their feet are not helpless human beings but rather malignant spirits or representations of those hostile forces that we need to overcome. By their example, the wrathful deities inspire courage and strengthen determination; greed and anger can be defeated, with the same energy and will shown by the warrior god.

Other supramundane beings stand watch at the entrance of a gompa, defending its sacred space against the malicious forces that seek to intrude. Some protect the law, others serve as personal guards, protecting believers against overt attack or the subtle, insidious, seductive dangers that arise within. The great beings, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, use these terrifying forms in order to transform destructive forces and impulses into beneficial spiritual aids.

Yab-Yum

If these ferocious, demonic figures are startling to the uninitated viewer, other tantric motifs and images seem even more shocking or bizarre. Tantric paintings and sculpture often depict a male and female deity locked in sexual embrace, an image known as "yab-yum," or father-mother. Seen without explanation, these images appear erotic and, if considered as devotional art, obscene and scandalous. Rather, the motif is to be understood as a visual symbol of a primary Buddhist teaching, as explained above: that enlightenment is obtained through the union of wisdom and compassion. The figures in a yab-yum image are thus symbolic, the male deity representing compassion, the female representing wisdom (insight), and their embrace is a visual metaphor for the rapture of union. Dualism, the illusory perception of independent existence and origination, is the source of egoism, ignorance, and suffering; union, the goal of the mystic, the fundamental objective of yoga, transcends polarity and leads to bliss. This is bodhicitta, the nonpolarized state, the recognition of indivisible, indestructible truth--enlightenment.

The yab-yum image, although esoteric (and sometimes restricted to initiates) is specific to Tibetan Buddhism, i.e., to Vajrayana, and is a central device in Tibetan art. It found no favor among the Mahayana Buddhists of eastern Asia, and does not appear in the art of China, Japan or Korea. But since sexual union is the fundamental means by which life comes into existence, Tibetans do not see this as an inappropriate symbol for the sacred mystery of ultimate spiritual communion. They were, moreover, influenced by Indian tantrism, with its esoteric doctrines and rituals. Although the female consort of a Buddhist deity is sometimes referred to as his shakti, that term derives from Hinduism, meaning power or energy, and in Hindu tantrism, the feminine is the active principle. Yet in Tibetan Buddhism these are reversed, with the female identified as prajna--wisdom or insight--and the male as means (which relates to compassion)--the means by which enlightenment is obtained, and thus the active component. Yab-yum figures may have a single head and two arms and legs, or they may have multiple limbs. The male figures may be dressed like Bodhisattvas, with ornaments and royal dress, or they may be dressed as Dharmapalas (see below).