Caturmahārāja : The Four Great Kings Mantra

The Four Great Kings are devas in the Indian pantheon where they occupy the lowest of the devalokas (god realms). They feature in some of the earliest Buddhist scriptures, representing a strand of Indian religous thought which was being adopted and adapted by Buddhists, probably in the first few centuries after the death of the Buddha. Each one presides over one of the four directions of space, and is associated with a particular type of non-human being.

These mantras are taken from the book Bonji Taikan which documents the Japanese Singon Siddhaṃ tradition.

Mantras of the Four Great Kings

Dhṛtarāṣṭra

King of the East. White in colour, holding a lute. King of the Gandharvas (celestial musicians). Dhṛtarāṣṭa means "watcher of lands".

There is a king Dhṛtarāṣṭra in the Mahābhārata. The war amongst his children and those of his younger brother Pāndhu for the throne of the Kurus - the Kauravas and the Pāndavas - forms the main action of the Mahabhārata war around which the epic revolves (Basham : 408). It is thought that the story recount a real war, although the dates are disputed.

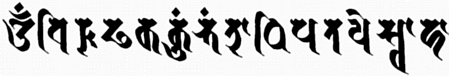

oṃ dhṛ ta rā ṣṭra ra lā pra vā dha na svā hā

oṃ dhṛtarāṣṭra ralāpravādhana svāhā

I have followed the spelling of Bonji Taijkan which I think is correct, but have also seen "dhṛtarāśtra" and "dhṛtarāṣṭṛa" in reputable sources.

Virūḍhaka

King of the South. Green in colour and holding a sword. King of the Kumbhāṇḍas, his name means "ever growing".

The Kumbhāṇḍas according to Sutherland are "a grotesque group of demons with testicles in the shape of a kumbha or pitcher". The Pāli commentaries describe them as having "huge stomachs, and their genital organs were as big as pots, hence their name". (DA.iii.964)

oṃ vi rū ḍha ka kuṃ bhāṃ ḍā dhi pa ta ye svā hā

oṃ virūḍhaka kumbhāṇḍādhipataye svāhā

"virūḍhaka kumbhāṇḍāye" can be translated Virūḍhaka Lord of the Kumbhāṇḍas. Bonji Taikan has "yakṣādhipataye" but properly speaking Vaiśravaṇa is Lord of the Yakṣas, and Virūḍhaka is Lord of the Kumbhāṇḍas. I have taken a liberty here (the kind that tests the patience of traditionalists), but one that makes sense. Sometimes the tradition is wrong, or corrupt.

Virūpākṣa

King of the West. Red in colour; holding a stūpa, and snake (or nāga). King of the Nāgas. His names means something like "all seeing".

Virūpākṣa's association with serpents and water suggests a connection with the Vedic god Varuṇa. Initially a solar god, often paired with mitra, Varuṇa was the guardian of ṛta - the cosmic order. Later, in the Hindu Epics, he was relegated to being a protector of water and was associated with water spirits, such as nāgas. Some scholars point to similarities with the Greek Titan Uranus (the names are phonetically similar).

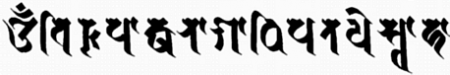

oṃ vi rū pā kṣa nā gā dhi pa ta ye svā hā

oṃ virūpākṣa nāgādhipataye svāhā

"virūpākṣa nāgādhipataye" can be translated as Virūpākṣa Lord of the Nāgas.

"Nāga" in Pāli and modern Indian languages means elephant, and is also sometimes applied to any large animal such as a bull. The Buddha is refered to a a great Nāga.

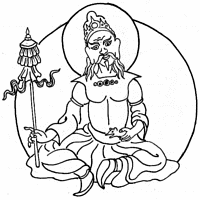

Vaiśravaṇa

King of the North. Yellow in colour. Holding a (victory) banner and mongoose spitting jewels. King of the Yakṣas

The name means..... Vaiśravaṇa is also known as Kubera under which name he appears in the Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa. He goes by the name Vaiśravaṇa in the Mahābharata where he is the son of Pulstya, and half brother of Rāvaṇa. Kunera is a god of wealth and good fortune - which is what the mongoose spitting out jewels symbolises. Vaiśravaṇa is the patron deity of the city of Khotan.

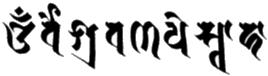

oṃ vai śra va ṇa ye svā hā

oṃ vaiśravaṇaye svāhā

This mantra is simply the name Vaiśravaṇa in the dative case (to or for Vaiśravaṇa) with oṃ and svāhā.

Notes on the Four Great Kings Collectively

A very early set of four directional gods appears in the Yajur Veda with Agni (E), Yama (S), Savitṛ (W), and Varuna (N). The gods of the directions were shuffled around in Brāhmaṇa texts. See also my essay on an early maṇḍalas, which discusses a maṇḍala in the Bṛhadāraṇuaka Upaniṣad. Scholars, however, place there origins of the four Lokapālas in the pre-Ariyan indigenous population of India. I favour a hybrid appraoch. Since some of the figures clearly do relate to Vedic gods in some ways (eg Vaiśravana and Kubera; Virūpakṣa and Varuṇa) I think that the Lokapālas, especially as we meet them in Buddhism, combine the chthonic local deities in the form of their follows (ie the yakṣas), but with Vedic inspired kings overlaid onto them. This is pure supposition however, and would need a lot more research to establish as fact.

The Lokapālas, or Mahārajas, feature widely in the Pāli texts (where they are known as the Cātummahārājikā), often visiting the Buddha at crucial times, or to hear the Dharma. In Pāli the names are: Dhataraṭṭha, Virūḷhaka, Virūpakkha, Vessavana. A summary of the Great Kings in the Pāli texts is available in the Dictionary of Pāli Names.

One of the key texts featuring the Four Kings is the Āṭānāṭiya Sutta (DN 32). This is one of the traditional paritta texts which are chanted for protection from misfortune, and the Āṭānṭiya is particularly concerned with protection from harmful 'spirits' ie yakṣas etc. Yakṣas etc were minor gods with their own cults and shrines. Several yakṣa (Pāli yakkha) shrines are mentioned in the Pāli texts. Initially they were not much distinguished from nāgas and were nature spirits associated with water or trees. In one text there is a story of an anger eating yakkha (SN 11.22).

One of the best known figures of the Vajrayāna, Vajrapaṇi, first appears in the Ambaṭṭha Sutta (DN 3) as the yakkha Vajirapani, the Pāli form of the name. He threatenes to split the head of a Brahmin, who is lying to the Buddha about his ancestry, into seven pieces. Head splitting is, strangely, a regular topic in the canon - in the Āṭānāṭiya non-humans will split the head of any malicious spirit who attacks one of the Buddha's disciples, as long as they recite the sutta (this is very reminiscent of later Mahayāna refrains!). Vajrapaṇi's progress to the pinnacle of the Vajrayana pantheon is traced in David Snellgrove's Indo-Tibetan Buddhism.

The Āṭānāṭiya continues to be an important text into the Mahāyāna, and continues to develop as a text for several centuries at least. Peter Skilling has traced its development in his study of the so-called Rakṣa [protection] texts. Later it is considered to be a kriya (or action) class tantra.

The Four Great Kings make an appearance in the Golden Light Sutra where they promise to protect anyone who recites the sutra. They are the rulers of the chthonic forces of nature. In this context they are known as the Lokapālas: "They belong to the heavens, but they are in touch with the earth, and they are therefore able to keep the powerful energies of the earth under control, and prevent them from having a disruptive effect on the human world." (Sangharakshita 1995: 134)

In maṇḍalas the Kings guard the four gates in the four directions. Vessentara describes these protector figures as "beneficient forces at the summit of the mundane world who, whilst not themselves Enlightened, are receptive to the influence of the Buddhas and Bodhisattvas". (308)

Maitiu O'Ceileachair has pointed out these type of mantras: beginning with oṃ, followed by the name of the deity in the dative case, and ending in svāhā, are similar in form to some Vedic Mantras from the Yajur Veda. What is suggested by this is that the mantra accompanied a libation (a liquid offering, probably ghee) poured onto the sacrificial fire and dedicated to the named deity. The form was retained even when the sacrifices were internalised, that carried out imaginatively, and the mantras on their own came to suffice for the ritual. Later again they were adopted by Buddhists wishing to invoke Buddhas and Bodhiattvas, and, as in this case, gods.

Source

- DN = Dīgha Nikāya

- SN = Saṃyutta Nikāya

- Basham, A.L. The Wonder that was India. (3rd rev. ed.) New Delhi : Rupa and Co, 2001 (1967).

- Bonji Taikan (梵字大鑑). Tōkyō : Meicho Fukyūkai, 1983.

- Piyadasi. Atanatiya Sutta : Discourse on Atanatiya. (DN 32, D iii 194). Access to Insight Website.

- Sangharakshita. Transforming Self and World : Themes from the Sūtra of Golden Light. Birmingham : Windhorse, 1995.

- Skilling, P. "The Rakṣā Literature of the Śrāvakayāna," Journal of the Pali Text Society. Vol 16, 1992, 109-82.

- Snellgrove, David. Indo-Tibetan Buddhism : Indian Buddhists and their Tibetan Successors. Boston : Shambhala, 1987, 2002.

- Sutherland, G. H. The Disguises of the Demon : The Development of the Yakṣa in Hinduism and Buddhism. Albany : State University of New York Press, 1991.

- Vessantara. Meeting the Buddhas : a Guide to Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, and Tantric Deities. Glasgow : Windhorse, 1993.