Tantric Images

The image of Buddha (Shakyamuni) known around the world is that of a seated figure in serene meditation--an icon recognized by people who know little else about Buddhism. Yet Tibetan Buddhism depicts deities whose appearance so contradicts the common expectation, that they are immediately misunderstood.

The sight of apparently demonic beings dancing on the walls of a sacred temple, alongside the expected images of tranquil deities with gentle faces, both misleads and bewilders uninitiated viewers.

As mentioned above, deities may appear in different emanations, in tantric as well as non-tantric form, in which case they are depicted as different beings.

The figures of horrific aspect are tantric. Seen within the same gompa, even side by side upon a wall, these contrasting images of serenity and ferocity provide a jolting change of visual rhythm, and an almost emotional dynamism.

These "terrifying deities" apparently derive from several sources. Some, such as Mahakala (see below), were absorbed from Indian Tantrism; others have a native Tibetan origin.

According to legend, when Padmasambhava came to Tibet to establish Buddhism, he encountered hostile local gods, whom he vanquished and bound over to serve the new faith. According to various theories, they may have been indigenous gods of the folk religion, or gods from the "old religion," i.e., Bon.

Armed and fierce, they guard the entrances to sacred places, combat evil, and show human beings the way to defeat negative emotions that block the way to enlightenment.

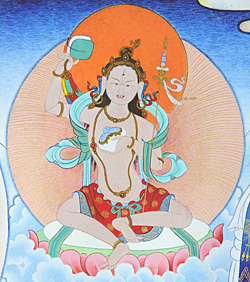

Tantric gods are depicted with thick limbs and powerful bodies, their faces contorted and grimacing, eyes glaring, fangs flashing in their open mouths. They brandish sharp weapons and their feet trample the bodies of small beings in human shape.

Their figures are cloaked in flame, their hair and eyebrows ablaze. Some wear a crown of skulls, others a necklace of severed human heads. Some drink blood from empty skulls.

Tantric deities may have a single head and two arms, but often they have multiple heads and limbs, and some have animal heads. Uninstructed viewers take them to be monsters, and wonder why they are given such prominent place on gompa walls or in thangkas.

But the recognition that deities may take such wrathful as well as peaceful forms is fundamental to an understanding of Tibetan iconology and art. It has also been observed that the terrifying deities harness or sublimate the violence that is a reality both of the cosmos and the human personality.

In Buddhist theory, these deities, although given human form (that is, with arms, legs, and faces) are personified visualizations of energy, determination, and invincible will--abstractions depicted through figurative representation.

In the same way, the peaceful deities are symbolic representations of compassion, wisdom, and insight.

The concept that a deity may have several emanations or manifestations, a feature common to both Hinduism and Buddhism, is one of the factors that has led to the multiplicity of divinities.

Thus Krishna, for example, is an avatar or incarnation of the Hindu god Vishnu, and the fierce Vajrabhairava is a manifestation of the Buddhist Manjushri, the great Bodhisattva of wisdom. The great Tibetan deities have multiple manifestations, thus adding to the complexity of Tibetan iconography.

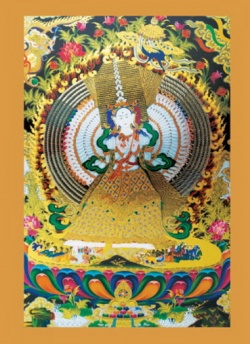

The relation of a deity to such emanations is sometimes visually represented by placing above the head of the god a smaller head or figure of the deity with which that god is spiritually connected.

Thus, a small image of the Dhyani-Buddha Amitabha is often depicted above the head of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara.

Some of the wrathful gods are manifestations of Buddhas and of the great Bodhisattvas, deities who have what might be described as a dual nature or dual capacity.

Yet other wrathful beings have a single nature--an independent identity. In either case, the wrathful, ferocious ones bear arms against destructive, negative forces: the passions of anger, hatred, envy, greed, and pride.

They are warriors against ignorance, selfishness and the rule of ego. This is the meaning of the weapons they wield: swords to cut through ignorance, axes to hack down anger, and lassos to snare ego.

Spiritual and psychological champions, possessed of tireless energy, their ferocious expressions reveal their determination to repel the subtle delusions that ensnare us, hindering human understanding of truth and ultimate reality, obstructing our path to liberation from suffering.

The wrathful deity Trailokya-vijaya deserves special notice here. Although not one of the very commonly depicted deities, he appears repeatedly in the Jampa mandalas (see Jampa gompa, below).

He is "the conqueror of the three worlds," a name signifying his victory over the enemies of the three worlds of the manifested universe: the celestial, earthly, and infernal realms.

The primary mandala of Jampa has been identified as the Vajrahadatu mandala, whose central deity is Vairocana; however, Trailokya-vijaya is known as an active or wrathful aspect of Vairocana, and as such he appears in several of the Jampa mandalas.

(Trailokya-vijaya is referred to in lines 56-59 of the Jampa Inscriptions: see below.) His color is blue and he is generally depicted with two of his hands crossed at his breast in the mudra known as vajrahumkara.

The little figures whom these deities trample beneath their feet are not helpless human beings but rather malignant spirits or representations of those hostile forces that we need to overcome.

By their example, the wrathful deities inspire courage and strengthen determination; greed and anger can be defeated, with the same energy and will shown by the warrior god.

Other supramundane beings stand watch at the entrance of a gompa, defending its sacred space against the malicious forces that seek to intrude. Some protect the law, others serve as personal guards, protecting believers against overt attack or the subtle, insidious, seductive dangers that arise within.

The great beings, Buddhas and Bodhisattvas, use these terrifying forms in order to transform destructive forces and impulses into beneficial spiritual aids.

If these ferocious, demonic figures are startling to the uninitated viewer, other tantric motifs and images seem even more shocking or bizarre. Tantric paintings and sculpture often depict a male and female deity locked in sexual embrace,

an image known as "yab-yum," or father-mother. Seen without explanation, these images appear erotic and, if considered as devotional art,

obscene and scandalous. Rather, the motif is to be understood as a visual symbol of a primary Buddhist teaching, as explained above: that enlightenment is obtained through the union of wisdom and compassion.

The figures in a yab-yum image are thus symbolic, the male deity representing compassion, the female representing wisdom (insight), and their embrace is a visual metaphor for the rapture of union. Dualism, the illusory perception of independent existence and origination, is the source of egoism, ignorance, and suffering;

union, the goal of the mystic, the fundamental objective of yoga, transcends polarity and leads to bliss. This is bodhicitta, the nonpolarized state, the recognition of indivisible, indestructible truth--enlightenment.

The yab-yum image, although esoteric (and sometimes restricted to initiates) is specific to Tibetan Buddhism, i.e., to Vajrayana, and is a central device in Tibetan art.

It found no favor among the Mahayana Buddhists of eastern Asia, and does not appear in the art of China, Japan or Korea.

But since sexual union is the fundamental means by which life comes into existence, Tibetans do not see this as an inappropriate symbol for the sacred mystery of ultimate spiritual communion. They were, moreover, influenced by Indian tantrism, with its esoteric doctrines and rituals.

Although the female consort of a Buddhist deity is sometimes referred to as his shakti, that term derives from Hinduism, meaning power or energy, and in Hindu tantrism, the feminine is the active principle.

Yet in Tibetan Buddhism these are reversed, with the female identified as prajna--wisdom or insight--and the male as means (which relates to compassion)--the means by which enlightenment is obtained, and thus the active component. Yab-yum figures may have a single head and two arms and legs, or they may have multiple limbs.

The male figures may be dressed like Bodhisattvas, with ornaments and royal dress, or they may be dressed as Dharmapalas (see below).

Source

http://library.brown.edu/cds/BuddhistTempleArt/TibetanArt3.html