Tang Dynasty Buddhists

Shan-tao

Shan-tao was an influential writer for the school of Buddhism, prominent in China, Korea, Vietnam and Japan. His writings had a strong influence on later Pure Land masters including Hōnen and Shinran in Japan.

In Jodo Shinshu Buddhism, he is considered the Fifth .

Biography

Shan-tao was born at Tzu-jou in the present Anhui Province. When he was young, he entered the priesthood and devoted himself to the study of the and the Vimalakirti Sutra. One day, in the year 641, he visited the temple of the famous Pure Land master, Tao-cho, who happened to be giving a lecture on the Contemplation Sutra. This lecture ultimately inspired him to follow, and then spread the .

In his lifetime, Shan-tao wrote five major works on Pure Land Buddhism, with his commentaries on the Contemplation Sutra being among the most influential.

Teachings

Shan-tao was one of the first to propose that salvation through Amitabha Buddha could be achieved simply through his name. The practice known as the nianfo as a way of singular devotion to Amitabha Buddha was all that was needed. In one of his more famous writings, Shan-tao spoke at great length about how simply saying the name of Amitabha Buddha was sufficient for salvation.

Prior to this, Amitabha was incorporated into wider practices such as those found in the Tien Tai school of Buddhism, as part of complex and often difficult practices. In later history, the ex-Tendai monk, Shinran, once commented that in his monastic days, he had to circumbabulate a status of Amitabha for 100 days straight without sitting down.

For example, Shan-tao once wrote:

"Only repeat the name of Amitabha with all your heart. Whether walking or standing, sitting or lying, never cease the practice of it even for a moment. This is the very work which unfailingly issues in salvation, for it is in accordance with the Original Vow of that Buddha."

Shan-tao often used imagery such as the "Light and Name of Amitabha" which "embraces" all beings. Ultimately, such writings marked a change in the way Buddhists viewed salvation through Amitabha.

Additional Information

- Inagaki, Hisao : A comprehensive look at Shan-Tao's life

- Ducor, Jerome : "Shandao et H?nen, à propos du livre de Julian F. Pas Visions of Sukh?vat?"; Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 22/1 , p. 93-163.

Posted by trouwaig at 1:58 AM No comments:

Nanyue Huairang

Nanyue Huairang was the foremost student of Dajian Huineng, the 6th Patriarch of Ch'an and teacher of one of his Dharma heirs, Mazu Daoyi. The ancestor of two of the Five Houses of Ch'an, Huairing studied with a Vinaya master and became ordained. Dissatisfied with his own progress, Huairang found Dajian Huineng in Shaozhou and became his disciple. One can read of their first meeting in the Wudeng Huiyuan. Huairang gave Dharma transmission to six individuals, the most prominent being Mazu Daoyi.

Posted by trouwaig at 1:58 AM No comments:

Moheyan

Heshang Moheyan was a late eighth century CE monk associated with the Northern School and famous for representing Chan vs. Indian Buddhism in a debate that is supposed to have set the course of Tibetan Buddhism. Hva-shang is a Tibetan approximation of the Chinese hoshang, meaning monk. Hoshang in turn comes from the Sanskrit title upadhyaya.

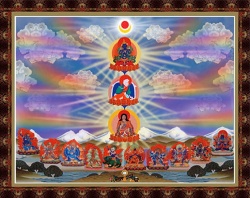

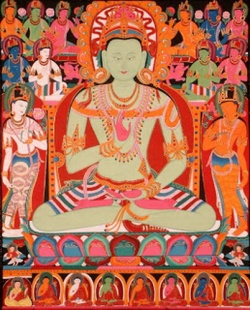

An iconographic thangka depiction of Moheyan is held in the Southern Alleghenies Museum of Art collection, St. Francis College, Loretto, Pennsylvania.

Dunhuang sojourn

Whilst the East Mountain Teachings were in decline, having been attacked by Heze Shenhui as a supposed "gradual enlightenment" teaching, Moheyan traveled to Dunhuang, which at the time belonged to the , in 781 or 787 CE. For Moheyan, this was a new opportunity for the spread of Chan.

Council of Lhasa

After teaching in the area of Dunhuang, Moheyan was invited by King Trisong Detsen of Tibet to settle at Samye Monastery, then the center of emerging Tibetan Buddhism.. Moheyan promulgated a variety of Chan and disseminated teachings from Samye where he attracted a considerable number of followers.

However, in 793 Trisong Detsen resolved that Moheyan did not hold the true Dharma. Following intense protests from Moheyan’s supporters, Trisong Detsen proposed to settle the matter by sponsoring a debate: dialectic is an ancient aspect of the and Chinese religions, as it is in Himalayan tradition. The most famous of these debates has become known as the "Council of Lhasa", although it may have taken place at Samye, a considerable distance from Lhasa. For the famed Council of Lhasa, an Indian monk named was invited to represent Indian Buddhism, while Moheyan represented Northern School Chán and Chinese Buddhism. Most Tibetan sources state that the debate was decided in Kamasila’s favour and Moheyan was required to leave the country and that all sudden-enlightenment texts were gathered and destroyed by royal decree. This was a pivotal event in the history of Tibetan Buddhism, which would afterward continue to follow the late Indian model with only minor influence from China. Moheyan’s teachings were a mixture of the 'East Mountain Teachings' associated with Shenxiu and Baotang Chán.

Moheyan’s teaching

Most of what is known of Moheyan’s teaching comes from fragments of writings in Chinese and Tibetan found in the Mogao caves at Dunhuang, Gansu, China. The manuscript given the appellation IOL Tib J 709 is a collection of nine Chan texts, commencing with the teachings of Moheyan.

Moheyan taught in the tradition of the “sudden enlightenment” school of Southern Chan . This dichotomy is a historical construction as both Northern and Southern Schools contained 'gradualist teachings' and 'sudden teachings' and practices. Moheyan held that all thought prevented enlightenment: “Not thinking, not pondering, non-examination, non-apprehension of an object---this is the immediate access ." He also believed that carrying out good or evil acts leads to transmigration rather than liberation as these acts “lead to heaven or hell.”

An important aspect of Moheyan’s teaching was that if all thought, good or bad, obscures enlightenment, then all actions must be based on the simplest principles of conduct. To achieve proper conduct, all conceptions, without exception should be seen as false: “If one sees conceptions as no conception, one sees the Tathāgata.” To rid oneself of all conceptions, one must practice meditation, trance, and contemplating the mind: “To turn the light towards the mind’s source, that is contemplating the mind. …one does not reflect on or observe whether thoughts are in movement or not, whether they are pure or not, whether they are empty or not.”

While Moheyan took a radical approach to the achievement of enlightenment , his position was weakened when questioned by, and entering into debate with, those people who could not meditate, who could not “turn the light of the mind towards the mind’s source.” He conceded that practices such as the “perfection of morality”, studying the sutras and teachings of the masters and cultivating meritorious actions were appropriate. These types of actions were seen as part of the “gradualist” school and Moheyan held that these were only necessary for those of "dim" facility and “dull” propensity. Those of “sharp” and "keen" facility and propensity do not need these practices as they have “direct” access to the truth through meditation. This concession to the “gradualists”, that not everyone can achieve the highest state of meditation, left Moheyan open to attack on the basis of a dualistic approach to practice. To overcome these inconsistencies in his thesis, Moheyan claimed that when one gave up all conceptions, an automatic, all-at-once attainment of virtue resulted. He taught that there was an “internal” practice to liberate the self and an “external” practice to liberate others . These were seen as two independent practices, a concession to human psychology and scriptural tradition.

Legacy

The teachings of Moheyan and other Chan masters were unified with the Kham Dzogchen lineages through the Kunkhyen , Rongzom Chokyi Zangpo.

The Dzogchen School of the Nyingmapa was often identified with the 'sudden enlightenment' of Moheyan and was called to defend itself against this charge by avowed members of the that held to the staunch view of 'gradual enlightenmnent' .

Iconography

According to Ying Chua , Moheyan is often depicted holding a shankha and a mala :

He is usually depicted as a rotund and jovial figure and holding a mala, or prayer beads in his left hand and a sankha, conch shell in his right. He is often considered a benefactor of children and is usually depicted with at least one or more playing children around him.

Primary sources

Moheyan . IOL Tib J 709 . Source:

Secondary sources

Electronic

- Schrempf, Mona . “Hwa shang at the Border: Transformations of History and Reconstructions of Identity in Modern A mdo.” JIATS, no. 2 : 1-32. Source:

Print

- Gōmez, Luis O, 1983, The Direct and the Gradual Approaches of Zen Master Mahayana: Fragments of the Teachings of Mo-Ho-Yen in Studies in Ch’an and Hua-Yen, Robert M. Gimello & Peter N. Gregory University of Hawaii Press, 3rd printing, ISBN 0-8248-0835-5

- Powers, John. History as Propaganda: Tibetan Exiles versus the People's Republic of China Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195174267

- Yamaguchi Zuihō. The Core Elements of Indian Buddhism Introduced into Tibet. In Jamie Hubbard and Paul L. Swanson , Pruning the Bodhi Tree: The Storm over Critical Buddhism Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-1949-1

Posted by trouwaig at 1:58 AM No comments:

Mazu Daoyi

Mazu Daoyi was a Ch'an Buddhist master of 8th century China.

Life

Mazu Daoyi was a master of the School of Buddhism. Mazu, whose family name was Ma ,

lived during the flowering of Ch'an under the Tang dynasty of China. A native of Sichuan province , during his years as master Mazu lived in province .

As a young man he studied with the sixth Ch'an , Huineng , near Guangzhou in Guangdong province. Later Mazu became a disciple of Huineng's student and successor, Nanyue Huairang , in Hunan province by . Mazu then became Nanyue's dharma-. Eventually Mazu settled at Kung-kung Mountain by Nankang, southern Kiangsi province, where he founded a monastery and gathered scores of disciples. After the sixth and last Patriarch Huineng, Mazu is perhaps the most influential teaching master in the formation of Ch'an Buddhism in China, from which sprang Zen in Japan.

Predecessors

Mazu Daoyi followed that may be said to commence with the Buddha or . In addition to his discourses recorded in the Sutras, the Buddha in person wordlessly gave Chan knowledge in embryo to , from whom it was passed on through a lineage, making transmissions across many generations. After perhaps a thousand years, these teachings were received by Bodhidharma who then brought them to China where he became known as the First Patriarch of Chan Buddhism. Bodhidharma's Chinese disciples, of course, understood his Buddhism in a Chinese context.

Huineng , the Sixth Patriarch, inspired new approaches, according to some interpretations, a Sinification of Buddhism. Chan Buddhism instructs practicioners to further their spiritual development, not by study of scripture nor by participation in ritual, per se, but chiefly through on-going encounter and the direct experience of his or her own human . It is through direct spiritual experience that might suddenly transform the consciousness of the practicioner. The primary method of putting this teaching into use had been meditation . After Huineng, the Sixth and last Chan Patriarch, a period of fresh experiment with different approaches ensued.

Teachings

Mazu Daoyi, in order to shake his students out of routine consciousness, employed novel and unconventional . He is credited with the innovations of using , surprise , and unexpectedly calling to a person by name as that person is leaving. This last is said to summon yeh-shih , from which enlightenment. He also employed silent gestures, non-responsive answers to questions, and was know to grab and twist the nose of a disciple. In the Transmission of the Lamp compiled in 1004, Mazu is described: "His appearance was remarkable. He strode along like a bull and glared about him like a tiger. If he stretched out his tongue, it reached up over his nose; on the soles of his feet were imprinted two circular marks." Utilizing a variety of unexpected shocks, his teaching methods challenged both habit and vanity, a push that might inspire suddenly the seeing of one's true nature .

Mazu was famous for the subtlety with which he expressed the Ch'an teachings; he was particularly fond of using the "What the mind is, what the Buddha is." In the particular case of Damei Fachang , hearing this brought about a spiritual awakening. Later this was contradicted by Mazu when he taught the kung'an "No mind, No Buddha." These two kung-ans may be seen as crafted paradoxes, meant to dislodge preconceptions, their cutting perplexity causing knots and hinderances to fall away from the mind, making way for spontaneous .

When sick Mazu was asked how he felt; he replied, "Sun Face Buddha. Moon Face Buddha." P'ang asked Mazu, "Who is it who is not dependent upon the ten thousand things?" Matsu answered, "This I'll tell you when you drink up the waters of the West River in one gulp." A monk asked Mazu, "Please indicate the meaning of Ch'an directly, apart from all permutations of assertion and denial." Mazu told him to ask Zhiang. Zhiang said for him to ask Baizhang. Baizhang said he didn't understand. The monk returned to Mazu and related what happened. Mazu replied dryly that Zhiang had white hair, and that Baizhang's was black.

Mazu: "et each of you see into his own mind. ... However eloquently I may talk about all kinds of things as innumerable as the sands of the Ganges, the Mind shows no increase... . You may talk ever so much about , and is still your Mind; you may not at all talk about it, and it is just the same your own Mind." A monk asked why the Master maintained, "The Mind is the Buddha." The Master answered, "Because I want to stop the crying of a baby." The monk persisted, "When the crying has stopped, what is it then?" "Not Mind, not Buddha," was the answer. Mazu listed "falsehood, flattery, self-conceit, arrogance" as impediments.

Successors

Among Mazu's immediate students were Baizhang Huaihai , Nan-ch'üan P'u-yüan , and Damei Fachang . A generation later his came to include Huangbo Xiyun , and his celebrated successor Linji Yixuan , as well as Kuei-shan Ling-yu , first of the Igyo school, and therein Yang-shan Hui-chi . The Igyo school's use of symbols influenced the well-known showing a water buffalo and a herder, which demonstrates various stages of growth in Ch'an awareness. From Linji Yixuan derived the school. These two schools merged in the 10th century. Later, Japanese Buddhists came to China to study at the Linji school. Taken to Japan in the 12th and 13th centuries, thrives today; use of the koan is a characteristic practice, fitting for distant spiritual descedents of Mazu. The long history of Buddhism in China has included forfeiture, and periods of syncretism; nonetheless, the Ch'an Buddhist tradition has been continued, e.g., by T'ai Hsü .

Chinese Sources

Mazu Daoyi's teachings and dialogues were collected and published in his Kiangsi Tao-i-ch'an-shih yu-lu . Mazu appears in early Chan anthologies, e.g., Transmission of the Lamp compiled in 1004 by Tao-yüan ; the renowned collection The Blue Cliff Record '' compiled with commentary by Yuanwu circa 1125; and The Gateless Gate compiled circa 1228 by . Other anthologies where Mazu appears include: ''Records of Pointing at the Moon , Recorded Saying of the Ancient Worthies , [[Records of the Regular Transmission of the Dharma]] .

Posted by trouwaig at 1:58 AM No comments:

Layman Pang

Layman Pang was a celebrated in the Chinese Chán tradition. Much like , who is said to have lived around the time of the in the 6th to 4th centuries BCE, Layman Pang is considered a model of the potential of the non- Buddhist follower to live an exemplary Buddhist life.

Originally from Hengyang in the province of Hunan, Pang was a successful merchant with a wife, son, and daughter. The family's wealth allowed them to devote their time to study of the Buddhist , in which they all became well-versed. Pang's daughter Ling Zhao was particularly adept, and at one point even seems to be have been more advanced and wise than her father, as the following story illustrates:

After Pang had retired from his profession, he is said to have begun to worry about the of his material wealth, and so he placed all of his possessions in a boat which he then sunk in a river. Following this, the family began to lead an itinerant lifestyle, travelling around China and visiting various Buddhist masters while earning a living by making and selling bamboo utensils. It was during this period, beginning around the year 785, that Pang began to study under one of the two preeminent Chan masters of the time, Shítóu Xīqiān , at , one of China's . Upon arriving at the mountain, Pang went directly to Shitou and asked, "Who is the one who is not a companion to the ten thousand ?" At this question, Shitou placed his hand over Pang's mouth. This gesture made a deep impression on Pang and his understanding of Buddhism, and he thereafter spent several months at Nanyue. It was sometime during this period that Shitou asked Pang what he had been doing lately, and Pang responded with a verse whose last two lines are well-known in Chinese Buddhist literature:

How miraculous and wondrous,

Hauling water and carrying firewood!

Pang eventually moved on from Nanyue to Jiangxi province, and his next teacher was the second preeminent Chan master of the time, . Pang approached Mazu with the same question that he had initially asked Shitou: "Who is the one who is not a companion to the ten thousand dharmas?" Mazu's answer was: "I'll tell you after you've swallowed in one gulp." With this response, Pang was . For this occasion—generally considered among the most important events in a Buddhist practitioner's spiritual life—Pang composed a poem:

the ten directions are the same one assembly—

Each and every one learns wu wei.

This is the very place to select Buddha;

Empty-minded having passed the exam, I return.

After staying with Mazu for a time to solidify his initial enlightenment experience, Pang then resumed his itinerant lifestyle, traveling with his family and stopping at various Buddhist temples and in his travels. One encounter that occurred in Guangxi province during this period of travel later became the basis for one of the ' in the collection Blue Cliff Record :

In 808, after many years of travel that had made him renowned in southern China, Pang became ill in Xiangzhou county of Guangxi province. His last words were spoken to the governor of Xiangzhou, who had come to inquire about his health: "I ask that you regard everything that is as , nor give substance to that which has none. Farewell. The world is like reflections and echoes."

Posted by trouwaig at 1:58 AM No comments:

Kuiji

Kuiji 窺基 , an exponent of Yogācāra, was a Chinese monk and a prominent disciple of Xuanzang.

Kuiji's commentaries on the Cheng weishi lun and his original treatise on Yogācāra, the Fayuan yilin chang 大乘法苑義林章 ("Essays on the Forest of Meanings in the Mahāyāna Dharma Garden" became foundations of the Weishi or Faxiang School.

The Faxiang School consider Kuiji to be their first patriarch.

Works

Commentaries

Commentaries specific to Yogacara

- Madhyāntavibhāga

- Sthiramati's Commentary on Asa?ga's Abhidharmasamuccaya

- Vasubandhu's Twenty Verses

- Vasubandhu's One Hundred Dharmas Treatise

- Yogācārabhūmi

Posted by trouwaig at 1:57 AM No comments:

Juzhi Yizhi

Jùzhī Yīzhǐ was a 9th-century Chinese Chán, or Zen, . After , he was the eleventh successor in the line of Nányuè Huáiràng and , as well as—according to some sources— . He was the student of Hángzhōu Tiānlóng .

Enlightenment

Gutei spent his time alone in the mountains, and chanting the Kannongyō, the of the Lotus Sutra. One day, he was visited by a young nun who lived nearby. The nun challenged Gutei to utter a word of Zen, but—when he proved unable to do so—she left. Having spent so much time in meditation and study, Gutei became dismayed at his inability to say a single word of Zen to the nun.

Shortly afterwards, Tenryū paid Gutei a visit. Gutei realized that his inability to answer the nun was due to his lack of understanding, and asked Tenryū to teach him. Tenryū held up his finger, and at that moment Gutei was .

Versions of this story are told by Taisen Deshimaru and Susan Ji-on Postal.

Gutei's Finger

Gutei is famous for the following story, which appears as a in various collections. The version here is from the Mumonkan, in the translation by Nyogen Senzaki and Paul Reps .

Gutei raised his finger whenever he was asked a question about Zen. A boy attendant began to imitate him in this way. When anyone asked the boy what his master had preached about, the boy would raise his finger.

Gutei heard about the boy's mischief. He seized him and cut off his finger. The boy cried and ran away. Gutei called and stopped him. When the boy turned his head to Gutei, Gutei raised up his own finger. In that instant the boy was enlightened.

When Gutei was about to pass from this world he gathered his monks around him. "I attained my finger-Zen," he said, "from my teacher Tenryu, and in my whole life I could not exhaust it." Then he passed away.

Mumon's comment: Enlightenment, which Gutei and the boy attained, has nothing to do with a finger. If anyone clings to a finger, Tenryu will be so disappointed that he will annihilate Gutei, the boy and the clinger all together.

Gutei cheapens the teaching of Tenyru,

Emancipating the boy with a knife.

Compared to the Chinese god who pushed aside a mountain with one hand

Old Gutei is a poor imitator.

It is due to this story that Gutei has commonly become known as Gutei Isshi, meaning "Gutei One-finger".