On Buddhist Thought

Why do you belong to your religion and not another?

Somehow it just 'fits' me. I have always been interested in philosophy and religion and was certainly looking for some kind of form that I could relate to, but nothing seemed to suit me. A bit like looking for a pair of shoes - you know you want something but don't know what it is until you see it; and then you have to try it on and see if it fits. On a more practical level I chose Buddhism because it allows freedom of investigation, the right to question - everything. The result of this is that generally it is a very tolerant religion. Buddhists have wars but never in the name of religion. Also Buddhism is not a belief system. There are suggestions made in the teachings but these don't have to just be blindly believed, they are to be investigated and examined in the light of one's own experience. Because Buddhism is relatively new in the West it is very fresh, vital and 'pure', which I very much appreciate. Institutions tend to get a bit stiff and stuffy over time and because Buddhism is quite 'fluid' it adapts well and can be easily repackaged; the contents are basically the same but a new face brings new life. Above all, Buddhism seems to make some sense, I can follow most of the logic without needing a mystical translator. Things are impermanent - yeah; there is suffering - yeah; things are the cause of other things - yeah; wanting causes suffering - yeah - and so on. Easy stuff.

What sets Buddhism apart from

other religions?

Outwardly there are obvious differences like dress, rituals, imagery, symbols, language, etc. On a doctrinal level one major distinction is that Buddhism is non-theistic - it proposes no creator God. While a whole cosmology can be found, with different heaven and hell realms, there is no suggestion of a single or separate being or thing 'in charge'.

What makes Buddhism truly unique is the teaching on impersonality or not-self - anatta. It is a difficult concept to grasp. The basic religious and philosophical question is 'who or what am I?' A classic Buddhist reply might be: 'a continually self-consuming process of arising and passing bodily and mental phenomena'. That's me huh? Nothing much. The Buddha proposed three conditions for all existence: impermanence, unsatisfactoriness and not-self. Following this logically we see that because a thing is impermanent it can't be relied on, it is ultimately unsatisfactory. Because it is unsatisfactory it is not suitable or wise to relate to this (or any)thing as ultimately who or what I am. I am not this, not that. Reversing this idea the search is then either for that which is truly permanent or for a non-relative identity. If my sense of self is not fixed as relative to anything then it has no substance, it is merely a process that can be observed and known.

What is it that knows?

Experience roughly divides into body and mind. Let's start with the body: It came into existence because of what? Parents, egg, sperm, nutrition, etc. It developed, evolved and is maintained because of ...? nutrition, parent personality, cultural situation, etc. Where is the two year old body now? Which bit is the same? A new body has surely been 'born', dependent on many conditions. And another ... and then another. This process of change removes any 'me' as a persisting factor. Try this exercise: imagine removing bits. Cut your hair off. Are you still there? Cut off a finger, a whole arm. Are you still there? How about two legs and the other arm? Are you still there? Yes, but there is a lot of pain. OK then let's do a heart and kidney transplant. Still there? And so on. Which bit of the body is the you bit? Buddhism would say no bit is ultimately a 'person', a you.

How about the mind? How long does any one mind state last? A second, a minute? And these mental experiences have come into being in the same way as the body - dependent on situational conditions. The thoughts and feelings are so fleeting, so transient that if I was to pick anything as being me I would choose the body. The paradox is: 'I feel as if I exist - but I can't put my finger on what it is that feels. ' Weird or what? Where does the answer lie? The Buddha placed tremendous emphasis on sati - usually translated as mindfulness or awareness, heedfulness, alertness, attentiveness, etc. It is the ability we have to know. You can look at these words, know that you see them - and know that you know. Seeing thought is not the same as thinking; knowing anger is not the same as being angry; and so on. The object is not the same as the knowing of it. Our habit is to absorb into the object of knowing to the degree that the object and subject relationship is lost and it all looks like one thing - ME. This is where meditation comes in - it narrows the field of activity so this process of object arising/changing and subject knowing can be observed and better understood. Another aspect is the investigation of differences between object and subject. Within experience are there any?

All this stuff is very subtle and it takes a while to 'get behind the scenes', but some appreciation of the principle of anatta is critical to having any real understanding of Buddhism which is why I have gone on a bit here. There are many books on this topic but an internal examination of the principle, using meditation, is the only true way to get any insight into this matter of being nobody, going nowhere.

Is Buddhism a religion, a philosophy, a psychology or a way of life?

It can function as any combination of these four depending on what you want to do. As a philosophy it provides very rational explanations on natural phenomena. The origin of the word philosophy is Greek and means 'lover of truth' which is what the Buddha was. As a psychology it gives tremendous insight into human behaviour, and as a way of life the basic model of the precepts, measured against the monk's rules, provides an excellent social formula.

However, as you might have guessed by my brief answers on the other options, Buddhism is a religion. The etymology of the word is: to bind, to tie up, to unite and the obvious question is: 'with what?' or 'to what?' In terms of basic experience: there is 'me' and there is 'other', and it is this other that is life's mystery. Some of it, like rocks and the speed of sound, can be explored fairly directly but - what's out there? where did it all start? what does it all mean? Religion is about transcendence - existence outside the immediately visible; freedom from the limitations inherent in matter - the nameless, the unconditioned.

What can Buddhism teach a person?

Lesson number one is probably on morality. Not so much a list of 'thou shalt nots' but a contemplation of the law of Kamma which ideally leads to a clear seeing that doing good things is more likely to bring good things in return than doing bad things. Cosmically it is a very precise law but personally it is not always so obviously fine-tuned, in that you may do something 'wrong' and seem to get away with it. Rebirth sorts that out in the long run.

There are many psychological tools available to work with the various confusions that seem to afflict us humans. Stress is a big thing these days and meditation is very useful in working with this. Various teachings on compassion and loving-kindness provide excellent lessons to loosen up the knots that form in the heart over the years. The most important lesson is on anatta, impersonality or not-self, which teaches us to not take it all so personally - and what a relief that is.

What are Buddhist views on animal testing and battery farming?

These probably weren't issues at the time of the Buddha so there is nothing specific in the scriptures. Probably the first reference point on Buddhist ethics is the 'five precepts'. Very briefly - not harming, not stealing, fidelity, right speech, sobriety. The 'five precepts' are guidelines or suggestions for living, not commandments. Buddhism generally doesn't 'lay down the law' but encourages people to look closely at their lives, their actions and see what the results are in the heart. Suggestions are given about behaviour that might add to one's suffering, but there is no ostracism involved for those that choose to not follow those suggestions. The general proposal is that 'if you live a moral life then your heart will more likely be at peace'. How you interpret and apply the five precepts in your life is up to you, but the Buddha clearly stated that a moral and virtuous life would lead to peace of mind and heart, and ultimately to enlightenment.

More specifically in relation to your question, I would personally consider the first precept of harmlessness as a reasonable statement against cruelty to animals. There is also a list in the scriptures connected with right livelihood (the fifth of the eight-fold path) that specifically mentions: trading in living beings, poison, slaughtering, fishing, and several other things as being wrong livelihood. Having said that, consider that these bodies of ours can only live if other life forms give their life - whether it is vegetable or animal it is still life. Who decides whether rats are OK for testing but not cats; monkeys but not dolphins? When a wild animal kills another, this is for survival. Is testing on a rat a part of the survival process of humans? Issues like vivisection, whether drugs should be legalised or abortion banned are social not religious issues, debated and agreed upon within our culture and society. Buddhism, as a religion, is about ultimate freedom (from suffering), Truth (with a capital T), and transcendence (of the conditioned world).

What obstructs us as individuals from realising this possibility varies from person to person and there is no black and white answer to the many questions life throws at us. It is interesting to see sometimes how violent people can become at, say a meeting or demonstration to promote peace and kindness. There are some very aggressive people in the peace movement. Some attempts to remove social injustice and suffering have ended in even greater injustice and suffering. An enlightened, egalitarian society is an ideal and certainly one that we can work towards as individuals, but it seems that injustice and suffering are an integral part of this earthly realm. There are two important things to bear in mind (1) what you personally choose to do - having reflected well on the result of those actions and (2) what suffering arises in your heart from expecting others to conform to your views.

Do Buddhists eat meat or drink alcohol?

The killing of animals for meat can be considered in relation to the first precept in a similar way to your question about animal testing. Vegetarianism is specifically mentioned in the scriptures related to an attempt by the Buddha's cousin, Devadatta, to take control of the order of monks. He reckoned the Buddha was too soft and presented a list of five demands for changes to the rules. One of these was that the monks should not eat meat. The Buddha refused to agree, and chucked out the other four demands as well. The logic behind his decision was that as alms mendicants monks should be grateful to receive whatever food lay people think is suitable to offer. There is also a rule that enables monks to refuse meat if they know that the animal has been specifically slaughtered for them.

Drinking alcohol relates to the fifth precept and the encouragement is to maintain clarity of mind. If the mind is clouded or confused then one's perception of reality (i.e. truth) will be distorted. As with all the precepts what you do is up to you - 'just a glass of wine with the meal?' 'Five pints down the pub relaxes me but doesn't cloud my mind'. I reckon save the money and meditate - but that's just me.

What do Buddhists think happens when we die?

When something changes it is a kind of death. The piece of paper this letter is written on will die. You screw it up and throw it in the bin. It rots away. It is dead. Where does it go?

When you were five years old you were different than you are now. You have changed. Where did the five year old you go? All you have left are memories and memories change as well. We forget things, memories die. Where do they go to? All the time your body is changing. After a while it conks out and what use is it? Where does it go? All the time your mind is changing. After a while it conks out, even before the body sometimes. Where does it go?

What the Buddha taught was that everything we do in this life has a result. Like an echo. I yell at you and you yell back. I steal your stuff so you steal mine. I love you so you can love me. So what I do now affects what happens later on. All my actions now affect how things will change. If I eat lots of junk food the skinny me will die and the fat me will be born. If I do lots of kind and useful things the unhappy me will die and the happy me will be born.

When we normally think of death it is the death of this body that we think of. The teaching on anatta says that this body is not who I am, so when this body conks out it is just like when my overcoat finally falls apart - the various elements go back to where they came from. This forms part of the Christian burial service: 'ashes to ashes, dust to dust'. What happens when the alive me dies? This is to do with the future which I don't know about. What I can fairly accurately predict is that if I am good now then it will be good later on.

It is useful to contemplate one's own death, the finiteness of the body. Imagine it getting old and weak and smelly. Not to get gruesome about it, but there are so few things in life we can be really sure of and death is one of them. We will all arrive at that door eventually. There is a special term used to describe the time when the Buddha's body conked out - parinibbana - final nibbana. Because he was enlightened there was no more rebirth, it was completely the end; unlike unenlightened beings who are reborn in some other form. What could that mean, completely the end? You'll just have to get enlightened and find out.

If Buddhists do not believe in a 'soul' or 'spirit' then what is reborn?

It's a tough one. Certainly something carries on, but what? The teachings always keep turning back to what is happening now, and actually discourage these kinds of questions. But one can't help wonder. Is it some kind of kammic DNA written and re-written in the cosmic register? St Peter with the big book certainly appears in Christianity. Is it a particular frequency of consciousness in the universal bandwidth? Could it be the last thought we have that jumps across? Could it be a deliberate choice by a disembodied consciousness? Could it be that my brain is starting to hurt?

The Buddha talked of four things which 'cannot or should not be pondered' and the inference is that they will addle the mind. One of the four is 'the result of actions' (vipaka-Kamma) - starting from birth and all the bits after.

In the cycles of rebirth, is there a finite

number of beings or can new ones be

brought into the world?

In a broader sense the question relates not just to beings but to matter generally. Is the amount of 'stuff' in the total universe finite? Is totally new matter generated anywhere or is it all just a rehash of the old, original stuff? In fact, was there ever an original creation? This is the fourth imponderable - brooding over the absolute beginning of the world (loka-cinta). In terms of beings in this human realm there seems to be no limit - they just keep popping out by the millions i.e. the population is increasing. When pressed on these kind of questions the Buddha would often reply: 'I teach suffering, and the path leading to the end of suffering'. Does knowing that Mrs Jones' cat has had a litter of totally new (not just recycled being-stuff), original kittens ease your suffering at all?

How does rebirth fit with evolution?

Evolution has to do with the material or conditioned realm. It is the relative shape, size, speed, colour, etc. of something. What exists now can be related to what existed say, 500 years ago and we can determine how it has evolved, for example, measuring the increase in height and life span of the average English person due to diet, evolved technology, etc.

Rebirth is about 'something' continuing to exist as an alienated, embodied 'something' and the manifold expressions of this embodiment can be seen as part of evolution. Measuring this over lifetimes is not something easily done. Using our memory we can measure change in this life. Reflecting on these memories we can (hopefully) come to conclusions about the worthiness of certain actions. This cause evolves into this result. Ideally evolution is about positive progress (rebirth), a learning from mistakes.

Evolution is always relative: seeing this thing, now, measured as different and separate from this (changed thing) later on. Buddhism is about unity not separation, communion not isolation. The aim is to be that which is not relative, is unconditioned, is not separate. This is about 'no-thing' which is beyond evolution. Conventionally we do things (meditate, be kind etc) now to bring about change in the future as a move toward enlightenment. This is all very heady stuff and while it is good to contemplate such things it is good not to be fixed on getting an answer.

What is reincarnation?

Reincarnation is usually thought of as coming back with another body after you die - after the death of this body. There is often an assumption in the theory that there is some kind of soul, something intrinsically 'me' that transmigrates. Before the question of reincarnation can be reasonably answered we must examine this assumption and ask 'who am I? what am I?' We need to know what it is that dies to get some idea of what might be re-born? In Buddhism the starting point is the proposition that 'I am not this body nor am I this mind'. What am I then? There is much that can, and has been written by way of an answer, but from a Buddhist perspective it is all speculative. It is not something that can be quantified, it is something that you directly experience. You know that you are, and you can know the experience of being alive, but how can you explain it. Science can give details of a great many of the components but fails to explain life itself. There are new sciences evolving (e.g. quantum and chaos) but will religion and science ever find a meeting point?

After this body breaks down (or does it break up?) what happens? I don't know. Life involves birth (creation, genesis, becoming), being (walking, eating, getting older), and ending (death, cessation, passing away). All of this is an expression of impermanence, change. The memories I have when I look back over 46 years are of a series of vignettes - this bit started, had a story line and then ended. And at the end of one, there might be a space of nothing particularly memorable and then another would begin; a continual round of births and deaths taking place. Is it the same me in each of those scenarios? Certainly I have a memory, like a snapshot in an album, but the photo is not me. Am I just the photographer? Or the camera? What is it that knows the memory? I think that somewhere in this ability to know, to be awake and aware, is where the answer lies.

Does reincarnation play a major role in your religion?

It does in the sense that it is clear that 'my business' doesn't end with the death of this body. This encourages me to see how important what I do today is - because it will affect how I am 're-born' tomorrow (or some time after 'now'). It makes me very careful about making decisions, about thinking a bit before I act. It makes me a bit more responsible because I have this sense that whatever I do, if it is tainted by greed or aversion or bound up with some ego view, then it will bounce back sooner or later.

Does Buddhism have a theory of interdependence?

Interdependence can be discussed in broad terms, related to nature as a whole; e.g. apples arise dependent on a tree, which in turn depends on the soil, the rain. . . and so forth and so we see that all things inter-depend. However my understanding is that the Buddha's teaching points to my own experience, especially the unpleasant aspects (dukkha), and to how I can be be free of that dukkha.

Firstly, there is the law of 'kamma' which is a teaching on moral cause and effect. Consider this in relation to Newton's law which says that: 'every action has an equal and opposite reaction'. If you hit someone - chances are that they will hit you back. This can be easily tested on material things but how does it functions in a moral context? How does my dukkha arise in relation to what I do? A (simplified) Buddhist reflection is 'do good get good, do bad get bad'. The Christian equivalent might be 'as you sow so shall ye reap'.

Then there is paticca-samuppada, the teaching on dependent origination, about which you might find many and varied explanations. It examines personal experience by considering the dependent relationship between 'ignorance' at the start (cause), with dukkha at the end (effect). The fundamental ignorance is holding to the view that there is a unique 'me' with a personal 'soul'. In paticca-samuppada, experience is divided into 12 observable links (some more observable than others). An easy bit goes: 'dependent on the sense s, contact with the world arises; contact produces feelings, leading to craving, to attachment; with all of it ending with old age, death, dukkha.

For convenience, and as a way of reflecting, we divide things and give the bits separate names; e.g. this body of ours = hands, feet, head, etc.; but there is just one body. Imagine you are in a tree, you slip, let go the branch (cause), and you fall. You know you are passing many branches but really all you register is the pain when you hit the ground (effect). Buddhism allows a separate reality (outside of my own experience) but focuses on my part in various cause(s) and effect(s) and says that I can choose - at least what I cause. You can test the truth of this for yourself. Try not to fall out of the tree?

Is Kamma the same as sin?

Literally Kamma means action; what I do. More specifically it is intentional action, either wholesome or unwholesome, and depending on the quality of the intention - depends the shape of my destiny. Unwholesome actions are those conditioned by greed, hatred or delusion. Some Kamma will ripen in this life and some in later lives. A question arises around the quality of intention; are good and bad absolute or relative? Is stealing £10 to feed my starving mother the same as stealing £10 to help pay off my gambling debt? The action is the same, the intention is different, but is the result the same? We can each of us only do what we think to be the right thing.

Sin is transgression of God's will and the separation from God arising from such transgression. Again the question of absolute value arises - is God's will fixed or relative? Kamma is all intentional action where sin is only unwholesome action.

Do Buddhists believe in God?

I have got a letter here from someone called Zara Holland. I don't really know even if there is a person called Zara Holland, maybe the teacher just made it up? But I have got this letter so maybe I can believe there is someone by this name.

I haven't got a letter from anyone called God, I have never met anyone called God. Is there any 'thing' that is God. I don't know. I haven't got a letter so I can't even believe. When I drop a rock on my toe I don't believe in pain, I KNOW pain - ouch!!!! When I am happy I KNOW that I am happy, I don't have to believe it. This is not to say that there isn't a God - but just that I don't know.

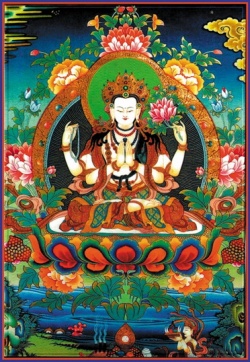

It also depends on how we define God? There is a tiered cosmology in Buddhism with gods, demons, devas and all sorts of other beings populating these realms (literal or mythological, I don't know). They are not seen as eternal or omnipotent. There is a story of a bhikkhu who wanted to know: 'where does the world cease without remainder?' He asked various sages on earth and it was suggested he try the gods. Cutting the story short he was progressively referred higher and higher until he reached the highest Brahman realm and approached Brahma in his court and asked his question. Brahma kept waffling and eventually took the man aside and told the man off for embarrassing him in public with a question he didn't know the answer to and that if he wanted to know he should go and ask the Buddha. This puts the gods into their relative position. As to 'a' God, the Buddha refused to answer the question which could leave open the possibility of such a 'thing' existing, but it would be safer to say 'no, Buddhists don't believe in God'.

Who or what do Buddhists worship.

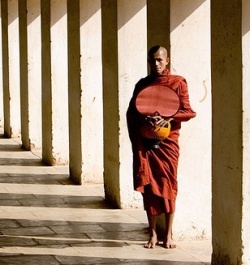

The Three Refuges would probably be the most common thing. The first is Buddha - both respect and veneration of the historical person who is now known as The Buddha - and a reverence and aspiration to that quality of wisdom, knowledge, enlightenment, that is Buddha. The second is Dhamma - having a great regard and appreciation of the teachings of the Buddha and a love of truth in the highest sense. The third is Sangha - honouring the qualities aspired to by the ordained community as a whole, rather than any one individual, which include goodness and morality. These three are all abstracts and there is no quality that is personified in any way. Even the man that was Buddha is seen as a historical event, whose memory is to be gratefully honoured but not to be created as anything separately immortal. What Buddhist worship - that is 'show profound religious devotion and respect to' (from my dictionary) - is Buddhism.

Why should I be good rather than bad?

Usually the strongest reflection is when you are found out. You do something 'good' for someone and they know it is you - or you do something 'bad' and they know it is you. What is your experience so far? Good and bad aren't absolutes, but we each have some kind of standard where we draw the line. What I use is 'the echo test'. When I do something I listen or watch for what comes back. Sometimes it is quite subtle - a nagging little mutter that comes up in my meditation or a gentle, warm feeling in the heart. Basically everyone wants to be happy, to be free from pain, depression, etc. and although there is no simple answer as to how to ensure happiness, doing good and avoiding bad is a pretty good start. Maybe you can do bad and it doesn't bother you. The Buddha encouraged people to experiment. Try it out, see for yourself. What are the results?

Do Buddhists believe there is a 'dark' side, like the devil?

Certainly there is goodness and badness. When you go into a room and maybe the two people in there have just had a row. They are just sitting there but you can feel the energy of their anger - the vibes. This is also true of goodness but it is often a bit more subtle. In the Buddhist cosmology there are several realms below the human one where all sorts of nasties hang out. This sort of 'energy', the vibe, the dark side ,does exist but is not embodied into any sort of fixed thing or character. Even life in the realm of the 'hungry ghosts' is not eternal. Can you see your own dark side? It is not a fixed thing and 'the devils' can be tamed and trained in goodness. It is difficult, but try and have compassion for those 'evil', lumpy, not-so-nice bits of ourselves and others. They can't be destroyed - only liberated.