Buddhist Monks and Politics in Sri Lanka

Buddhist Monks and Politics in Sri Lanka

James J. Hughes

Presented at the April, 1987 Spring Institute for Social Science Research

University of Chicago, Chicago

Introduction

- It was to help humanity that the Buddha founded the Order. He intended it to be a voluntary association of dedicated persons who would devote themselves to the task of making the process of wayfaring through life easier for such among their fellow beings as were weak, helpless and stricken.

- It is another matter that the order never quite became what it was meant to be. The Bhikkhus (homeless ones) very soon became Priests, living in temples built like palaces. Today the lazy and ceremonious Church, split into Nikayas based on caste divisions, maintains its place in society, not by tendering to the sick, the poor and the helpless but by placing a Messianic halo above the Buddha-myth, and by chanting faint Pali gathas to the cold, fruitless moon.

- J.R. Jayawardene, Sri Lanka's President 1977-1987, A Life of Service 1942

In the last thirty years, neo-Marxist [1] black and feminist social historians have challenged the older Marxist and functionalist views of religion as a "false consciousness" repressing class struggle or as a force for social stability. These new sociologists of religion have portrayed religious institutions and theological worldviews as expressive of class and power struggle, rather than of monolithic ideological hegemony; the interests of the less-powerful have been found to be expressed through and in religion. A diverse body of work has developed discussing the role of religious professionals in the struggles for empowerment of classes, races, nations, and women.

One of the major tributaries to this theoretical stream comes from Antonio Gramsci and his powerful conceptualization of the relationship of culture and power. Gramsci suggested that subordinate classes had a latent "critical consciousness", a latent cognizance that the hegemonic worldview and social order tended to serve the interests of the ruling classes. The intellectuals directly rooted in these subordinate classes, those who have the opportunity and training for reflection in their institutional roles such as doctors, clerks, teachers, clergy, these "organic intellectuals" may mobilize this latent critical consciousness in a "counter-hegemonic" "war of position" against the hegemonic powers. Gramsci wrote that the role of the revolutionary party was to develop a new organic intellectual leadership from the peasants and workers. From the vantage point of Gramsci's Italy, most clergy and other categories of traditional intellectuals were organically tied to the upper classes, and thus not the basis for radical social change. The lowest plebian clergy could, however, be "organic intelligentsia" of the peasantry.

Recently, scholars have begun to suggest a differentiated roles, neither wholely elite nor wholely insurgent, in class struggle for the Thai Buddhist clergy (Suksamran, 1982), the Burmese Buddhist clergy (Sarkisyanz, 1965), for the Sri Lankan Buddhist clergy (Rahula, 1956, 1974; Houtart, 1974, 1977; Phadnis, 1976; Jayawardene, 1979; Malagoda, 1976), and even for the early Buddhist movement in ancient India (Sankrityayan, 1973; Ling, 1973).

A major goal of this study was to use this Gramscian concept of organic plebian clergy to examine the political and economic role of Buddhist monks in rural Sri Lanka. A central assumption of this study was that organic intellectuals of the peasantry would act as advocates of the interests of their base, and that in the Sri Lankan context "advocacy" would be expressed either through social service organizing, or left-populist political activism. Monks who are structurally allied with the middle and upper classes would tend not to become involved in social service advocacy or left-populist activism, while monks directly financially dependent on the voluntary support of poor villagers would tend to become involved.[2]

Though the structural position of a monk, along with his personal history and ascribed characteristics, would all tend to predispose a monk to adopt a pro-plebian or pro-elite stance, the streams of ideological discourse in which monks are embedded are rarely purely "hegemonic" or "insurgent". In the Sri Lankan context, monastic social and political attitudes tend to vary along a continuum of traditionalism to radicalism. The "hegemonic" model for the monk is as a "spiritual" rather than "this-worldly" guide for the people, except when the Sinhalese people and religious culture are "threatened", at which time the Sri Lankan clergy have a racial-national responsibility to assume leadership, as "inscribed" in the religio-historic chronicle the Mahavamsa. Those monks who claim that they are acting on the basis of this historic racial-national responsibility range ideologically from cosmopolitan elite patrons of philanthropy to proto-fascist populists.

At the farthest end of the activism continuum from the inactive traditionalists are the Left monks, those for whom political activity is seen more in terms of class and anti-imperialism than race and religion. Both Left and traditional elements are present in thinking of most monks, but the suggestion here is that the monks with the clearest organic ties to the subordinate classes would be more likely to adopt insurgent ideology, and consequently engage in more insurgent organizing. Finally, both insurgent and hegemonic ideologies vary along a continuum of Mahavamsist to Cosmopolitan. The more urban monks, and the monks with more secular education, tend to adopt more cosmopolitan worldviews, ranging from Marxism to conservative views of one sort or another.

Table One: An Ideological Matrix of Sri Lankan Monks

| Mahavamsist Worldview | Cosmopolitan Worldview | |

|---|---|---|

| Structurally Elite | Religious role to Social service to Rightist activism |

Religious or academic role (inactive) to Philanthropic social service |

| Structurally Plebian | Social Service/ Populist activism |

Social Service/ Left political activism |

The suggested model is not a static one. In the struggles between the plebian and elite monks within the Sri Lankan Buddhist clergy no one Buddhist sect, movement or leader has ever been wholely popular or elite. [3] There have always been many cross-cutting vectors and structures which have come together to the create the complex, and constantly changing, reality of the Sangha. But one of the most important set of factors pre-disposing monks toward one or the other tendency, however, seems to have been the personal background and structural ties of the monks to elite or non-elite groups in secular society.

The following plebian-tending or elite-tending factors have been suggested in the literature as being determinative of monks' socio-political activism:

Table Two: Cross-cutting but Correlated Divisions in the Sangha

| Popular Factors | Elite Factors |

|---|---|

Ascribed characteristics | |

| 1. low-caste status | 1. high-caste (goyigama) |

| 2. young monks | 2. old monks |

| 3. nuns/sil matas | 3. monks |

Background socialization | |

| 4. monks from poor families or villages |

4. monks from wealthy backgrounds or cities |

| 5. Amarapura or Ramanna sect membership |

5. Siyam sect membership |

Organic Base 6. landless, poor temple 6. rich, landed temple 7. temples dependent on poor patrons 7. temples dependent on elites Feudal/insurgent cultural milieu 8. Southern, low-country temples 8. Kandyan, up-country temples

The monks' interdependence with class and other power contradictions in society have not only been expressed in their social alliances, but also in dissension and struggle within their orders. For instance poor, low-caste monks have not only consistently attacked the colonial and aristocratic allies of the upper-caste Siyam-sect hierarchs since the nineteenth century, but also demanded the redistribution of the Siyam's property, and substantial reduction of the autonomy of all the sects (Abeyasinghe, 1979; Evers, 1972; Katz, 1984; Malagoda, 1976; Phadnis, 1976; Smith 1966b).

The granting of land by the aristocrats and king to the temples led to solidarity between the land-owners, the state and the wealthy temples' incumbent clergy. In fact, the state ultimately enforced the Sangha's appropriation of rice. For instance, monks led a revolt against the colonial powers in 1848 when the British decided to stop enforcing the "customary" rice tithe of the sharecroppers of temple lands to their monastic landlords; the monks were driven to insurgency by their hunger (de Silva, 1941). The accumulation of monastic property in the medeival and colonial periods encouraged the internal differentiation of, and conflicts within, the Sangha, and thus necessitated the growth of strong, centralized sect structures to mediate these conflicts between monks over property, as Gunawardana (1979) shows for medeival Anuradhapura.

These hierarchical sect structures, controlled by wealthy clerical elites, allied politically, economically and through kinship with the aristocracy, also allowed the maintenance of the political and ideological hegemony of these elites over the plebian, propertyless monks at the base; monks and temples not allied with the dominant sects were frequently accused of heresy and became the subjects of clerical and political persecution. Periodically, as the temples became obscenely wealthy and lost their legitimacy for the public, and thus their ability to legitimate the social and political order, ascetic movements split off which attracted pious lay patronage, became rich and powerful, and spawned new reform sects. Even the religious ideologies of these competing monastic groups were never purely "insurgent"; any particular religious expression, being the result of social struggle, necessarily included elements which both potentially undercut and reproduced social power relations.

The monks not only monopolized religious legitimation, but also education. In the pre-colonial period the only formal education available was to be found in the temple. As the sole teachers and knowledge producers for their society, the monks shaped the world views of the people in their own interests, and in the interests of those with whom they were inter-dependent, the aristocracy and royalty. One the main spurs to the anti-colonial/anti-Christian militance of the disenfranchised, low-caste monks of the nineteenth century was the threat to the clerical monopoly on edcuation posed by the Christian missionaries.[4] The missionary school training of an indigenous Tamil and Sinhalese elite to administer Sri Lanka for the British was accompanied by the conversion of these indigenous elites to Christianity. Though the conversion of Sinhalese elites to Christianity threatened even landed, upper-caste monks' organic connection to power, the landless, low-caste sects along the Southern coast were directly economically threatened by this disenfranchisement. The Kandyan, Siyam monks just grumbled, while the low-country plebian monks became leaders in anti-colonial agitation.

Unfortunately it was also in this early anti-colonial period that the low-caste coastal merchant elites, allied with certain fiery monks, drew together the modern Sinhala chauvanist mythos in their struggle against colonialism. The first aspect of the mythos was the claim that the Sinhalese were the pure-blooded descendents of the 'Aryans" who had conquered the darker-skinned "Dravidians" of South India thousands of years before. The Sinhalese were thus the "racial equals" of the Europeans, and, in fact, during the rise of German fascism, some Sinhalese repeated the Nazi call for Aryan racial purity.

Another element was the myth that the Sinhalese race was founded by a North Indian "Aryan" prince named Vijaya who came to Lanka in the 6th century conquering the native aboriginal peoples. Though he and his men married South Indian Dravidians he was supposedly the founder of the pure Sinhala race. In fact, there has been such a degree of intermarriage and cultural intermixing of South Indians and Sinhalese, that it is hardly correct to consider Sinhala culture, language or religion a unified tradition, much less the Sinhalese and Tamils as distinct races.

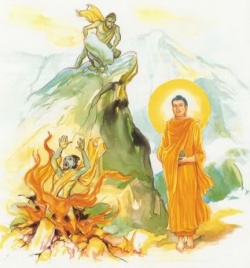

The Mahavamsa chronicles provided another strand of the Sinhala mythos. The monks who composed the Mahavamsa asserted that the Buddha had entrusted the care of pure Buddhism to the Aryan Sinhalese on this sacred island after driving off the aboriginal "demons" living there; from then on, whenever the island was invaded, it was to be reconquered in the name of Buddhism. The central figure of this "reconquest mythos" is the young warrior Dutugemunu (161-137 B.C.), accompanied by 500 Buddhist monks and a monk-general, as he mounts a relic of the Buddha on the end of his spear and sets out to reconquer Sri Lanka from the South Indian kings. After slaughtering thousands, Dutugemunu is stricken with guilt, and dread of the karmic consequences of his acts. But monks in attendence consoled him that since there had only been one man who had taken Buddhist precepts and another who had taken refuge in the Three Jewels, there had therefore been only one and a half "human" victims.

- The origination of a historical literature in Ceylon in the existing form was an intentional act of political relevance. Its object was the propagation of a concept of national identity closely connected with a religious tradition, i.e. the identity of the Sinhalese Buddhists. This idea has shaped the history of Ceylon from the days of the earliest chroniclers to the present day in its particular way. Without the impact of this idea, the remarkable continuity of the cultural as well as of the political traditions in spite of the vicissitudes in the history of the island would have been impossible. Its impact has at the same time, entirely changed the Asokan ideology (the original model for king-Sangha-people unity). For Asoka, the idea of a non-denominational welfare-state was born from the inner conflict of the king resulting from his repentence of the war he had made before his conversion to the Buddhist religion. For the author of the Mahavamsa, on the other hand, the war of Dutthugamani against the Tamil invaders was by no means a problem of religion and morality, but it was an act of justified politics.

- Bechert, 1978, p.7

In other words, out of the need to mute the progressive and critical strains in the Buddhist tradition, and develop religious legitimations of the feudal social order, Buddhist monks developed a racial-nationalist ideology. As long as the rulers of Sri Lanka were non-Buddhist and non-Sinhala, such as the British or the English-speaking Sinhalese Christians, this ideology could be turned to the purposes of insurgency; in other words, the ideology, though largely tending to reproduce the social order, included elements which could be used for subversion.

With the rise of the Sri Lankan Left after the turn of the century, however, a new vector of "insurgency" was introduced: exposure to Western political ideologies, in particular Marxism. Monks who were otherwise "structurally elite" began to adopt insurgent politics after education in secular institutions, or political socialization in anti-imperialist popular front groups. The first struggles for monks' political activity to be acknowledged as legitimate was in fact waged by relatively advantaged Trotskyist monks at universities in Colombo in the late 1940's.

Though monks from the elite and racial-populist Right have been equally involved in political activity in the twentieth century, they organize under the banner of Sinhala-Buddhist culture and tradition, and thus are seen as orthodox, while the class-conscious monks of the Left speak a Marxist discourse tied more loosely to Sinhala-Buddhist tradition. There is a double standard: criticisms of "monks getting into politics" are generally criticisms of Leftist monks, ignoring equally active Rightist monks.[5] Consequently, Left monks approve of "monks' politics" openly, while Right monks, who may be equally politically active, disapprove. (This does not hold for lay Leftists, who are generally more concerned with the political activism of Rightist monks, and thus also oppose monastic political activism in general.)

Another hypothesis of this study was that there was a continuum of activities that insurgent monks who sought to advocate the interest of the poor would tend to approve of and carry out. The activities along this advocacy continuum were hypothesized to range from the traditional monastic roles of religious instruction, to social service activities, to direct political "advocacy".[6] The research was in fact begun with the goal of examining the role of Buddhist monks in rural social service work, and an attempt to identify which monks would be the best to train for a role in rural development.

The organization sponsoring the research was Sarvodaya Shramadana, a 25 year-old integrated rural development movement in Sri Lanka. Sarvodaya had been begun by Buddhist populists during the late fifties, when the country was the scene of a political struggle between the Anglo-Christian United National Party (UNP) and a coalition of Buddhist-populist and Left parties. The Buddhist-Left coalition mobilized up to a quarter of the Sri Lankan clergy in its electoral "Sinhala Buddhist Revolution".

In the midst of this broad ferment a young Buddhist school-teacher decided to adapt Gandhian concepts and strategies of rural "re-awakening" (Sarvodaya) to Sinhalese culture. Though Sarvodaya started as a clique of middle-class Buddhist students of this teacher who went into the bush for weekends to help the poor, the program developed during the Sixties into a philosophically sophisticated and charismatic movement. Like the Sri Lankan Freedom Party (Perera, 1982), Sarvodaya's rural cadre came to center on politicized monks, Sinhala-medium school-teachers (Macy, 1983).

The first step of the Sarvodaya strategy is to have these organic intellectuals organize a shramadana, a work camp addressed to some pressing village need, such as cutting a road or the construction of a meeting hall. The shramadanas are begun and ended with religious ceremonies in which the collective "donation of labor" (shramadana) is equated with the meritorious activity of giving food to monks (dana). Out of the organizing around the shramadana, a Sarvodaya committee is then formed and subsequently groups are organized for youth, mothers, farmers and children. Usually the mothers' group then sends a young woman for preschool training and establishes a preschool at the temple or community building. On top of this social infrastructure Sarvodaya aims to develop the economic self-reliance of the village through community industries and income-generating projects, and to work on the improvement of the health and education of the villagers.

After the program began to rapidly expand in the 1960's, and to receive substantial European funding in the 1970's, it began to systematize the training and organization of its secular and monastic cadre. The Pathakada Bhikkhu Training Center was established to train monks in economics, health, education and Sarvodaya philosophy. Following the abortive Maoist youth insurgency of 1971, Sarvodaya's leading monastic cadre organized into the Sarvodaya Sangha Samanelya (Sarvodaya Monk Front) to defend the movement from the subsequent authoritarian repression of the populist-Communist coalition government. The absorption of young, educated, unemployed, former insurgents into the expanding Sarvodaya cadre generated further government hostility, while stengthening the movement.

Following the return to power of the pro-American, free market-oriented UNP in 1977, however, Sarvodaya was enthusiatically embraced by the government which adopted much of its terminology and rationale in its own rural development program. The tacit political alliances between the pro-American UNP and Sarvodaya built during the years of Left authoritarianism, along with the eagerness of fiscal conservatives to use Sarvodayan "rural self-reliance" as a rationale for cuts in the social service budget, combined to intensify Sarvodaya's steady drift to the center and isolation from the Left. As compared to the sixties and early seventies, Sarvodaya's political discourse shifted from anarcho-socialist populism to a pious volunteerism.

Another question guiding the research then was what the consequences were of the alienation from Sarvodaya of monks who were otherwise committed to advocacy. In particular, did the rural plebian and cosmopolitan Left monks approve in general of the type of social service work that Sarvodaya did, while rejecting Sarvodaya? And if the plebian and Left monks were rejecting Sarvodaya, were the monks joining Sarvodaya more right-wing; in the Sri Lankan context, were Sinhala chauvanist monks being attracted by the movement's Sinhala-Buddhist revivalism?

Four lay groups were examined to allow the testing of the model of "insurgent-tending factors" in a more indepth case study setting. Different leadership dynamics were hypothesized in villages in which, on the one hand, the monk and his supporters were poor, low-caste, and in an area of insurgent politicization, and on the other hand where the monk was not organically dependent on poor, low-caste politicized tenants. According to the model of organic intellectuals catalyzing the latent critical consciousness of the peasantry, plebian clerics involved in improving the lot of their parishioners through social service and/or political activism would meet with more approval than monks who weren't organically tied to the majority of their villagers and working in their interests; i.e. who weren't critical organic intellectuals. According to Sarvodaya's development theory, a monk is an ideal "rural change agent" because he is invested with a sacred aura which allows him to mediate the social divisions in a village. In Gramscian terms, however, though structurally elite monks may successfully exercise religious/ideological hegemony over the peasantry, binding them to the status quo, to the extent that the peasantry's critical consciousness is manifest such monks should be unpopular.

Data and Methods

The survey was designed in October 1983 to be used on both the lay and monastic samples. After having been written in English it was translated into Sinhala. Over the course of the next six months it was administered to four lay groups and five monastic groups. All the surveys were distributed and collected over a period of several days.[7]

Table Three: Surveys Samples Taken

Lay Samples return total % ave. date

rate sample female age taken

1. Volunteers & workers at

Sarvodaya's Central Office 50% 30 65% 33 Oct'83.

2. Villagers of Village A, Wellawaya District 90% 95 50% 35 Oct'83.

3. Villagers of Village B, Kandy District 75% 125 60% 35 Dec'83.

4. Students, sociology class, Sri Jayawardenepura Univ. 100% 27 55% 23 Jan'84.

Monastic Samples 5. Dharma teacher trainees, D-school (Pirivena) 75% 29 none 29 Nov'83.

6. Trainees in dharma-teaching & social-service, at M-Center (Bhikkhu Training Center) 75% 19 none 25 Dec'83.

7. Trainees in a 4-month social-service course at Sarvodaya's Pathakada Bhikkhu Training Center 90% 15 none 23 Jan'84.

8. University student bhikkhus 75% 19 none 25 Jan'84. 9. Leaders of Sarvodaya's

Sangha Samanalaya (Front) 95% 20 none 27 May'84.

Village A and B were recommended by Sarvodaya personnel in response to my request for fairly representative villages in Kandy and the South with roughly comparable periods of Sarvodaya organizing and sizes of projects undertaken. Village A was located on a remote mountaintop in a low-caste, traditionally left-leaning area, while Village B was along a "major" road in the central Kandyan highlands, an area considered more traditional and feudal in orientation. Extensive interviewing was conducted during two-week stays in both villages, as well as discussions with Sarvodaya personnel about their experiences with the villages.

In addition to the collection of survey data and the conducting of a number of interviews with monks and lay people during my two-year stay in the island, I also ordained for a one hundred-day period as a Buddhist monk at Sarvodaya's Pathakada Training Center. The majority of that time, ten weeks, was spent at a Sarvodaya temple near the headquarters. During these ten weeks I was under the guidance of a meditation-oriented Sinhala monk. This period was very valuable, not only personally, but from a research viewpoint as well, for it was a concentrated lesson in the monastic disciplines which, however laxly observed, form the framework of monastic life. Short stays at other temples during this period provided insightful contrasts.

What Sarvodaya Workers Believe

Before examining the data, it is useful to know just what attitudes the Sarvodaya organization as a whole actually has towards monks' legitimate role in the development process, aside from the ideological discourse disseminated from the headquarters. Wismeijer's 1984 survey of Sarvodaya leaders and monks focused on this question. His sample was made up of 260 lay Sarvodaya leaders and 43 Sarvodaya monks, including all the members of the Executive Council, all the section heads at Sarvodaya headquarters, all district coordinators and heads of Educational Institutes, regional coordinators, the chairmen of the village Sarvodaya committees and random samples of full-time workers from the headquarters to the grassroots. One question Wismeijer asked was "How would you describe the role of a bhikkhu in development?". He divided the answers into eight categories:

Table Four: What is the Monk's Role in Development?[8] (N=245)

46% As a teacher of moral/religious tradition; ceremony organizer

29% Social service: to help the needy

9% As a teacher in secular community education

9% To improve people's material condition with economic advice

8% Propagation and organizing of Sarvodaya

6% By leading an exemplary life, and striving after enlightenment

4% Through politics; becoming advisors to politicians

Then Wismeijer asked the respondents to rank nine activities of monks in terms of importance:

Table Five: Importance of Monks' Various Activities (N=228)

MOST IMPORTANT

Teaching Religion 90% "very important"

Meditation 78% "very important"

Chanting Blessings 55% "very important"

MODERATELY IMPORTANT Social Service 90% "very important" or "important"

Organizing Shramadana 89% "very important" or "important"

Economic Advice 79% "very important" or "important"

UNIMPORTANT

Ayurveda (medicine) 35% "not important"

Astrology 59% "not important"

Politics 89% "not important"

The Sarvodaya workers clearly ranked social service as second only to the religious role of the monk, while they ranked direct political advocacy as even less legitimate than the practice of traditional medicine and astrology, "black arts" which are clearly forbidden in the monastic disciplinary code. A special focus of Wismeijer's study was the controversial monastic disciplinary issue of monk's engaging in manual labor. He asked Sarvodaya workers their attitudes toward monks taking physical roles in shramadana, and he found a much higher level of approval among them than others have found in the general population. A third of the respondents unconditionally agreed with monks' taking part in physical labor, and another 20% agreed with certain conditions. In general, most lay Sarvodayan and even higher percentages of Sarvodaya's monks, would rather have monks violate the letter of their disciplinary code than engage in political advocacy.

The Monks' Survey Data

The main purpose of the monastic survey samples was to test the internal coherence of the hypothesized dependent variables, the views held by monks about social service work, politics and Sarvodaya, rather than to draw inferences about the numbers of Sri Lankan monks holding any particular views. Two of the independent variables described in Table One were included in the survey: sect membership and age. A monk's caste was inferred from his sect membership, as explained below. The other independent variables, the wealth of a monk's family, temple and parishioners and the feudal culture of the area, were examined in the two village case studies.

Attitudes Toward Sarvodaya There were few people in either the monastic or lay samples who expressed direct disagreement with Sarvodaya. Most of the variance came between those who "strongly agreed" and those who "agreed somewhat". Those monks who believed that Sarvodaya was "political" basically disagreed with Sarvodaya's politics. In particular, university monks tended to disagree with Sarvodaya on the basis of its political relationship to the Sri Lankan government. Belief that Sarvodaya was a "political" movement was significantly related to monks' disagreement with Sarvodaya.

Figure One: Attitudes Towards Sarvodaya

N=93, all sig<.01

Monks who disagreed with Sarvodaya politically also, logically, tended to believe that it was not appropriate for monks to teach Sarvodaya philosophy. Conversely, some monks disagreed with Sarvodaya precisely because they resented the growing pressure on monks to become involved in social service. Few monks felt social service work in general (apart from controversial activities such as physical labor) was inappropriate for other monks, but quite a few obviously felt it was inappropriate for themselves, and disliked being seen as socially irresponsible in contrast. The above three questions then were put together in a scale to measure "pro/anti-Sarvodaya-ness".

Social Service and Political Activism Ordering the social service and political activities according to the percent of monks who explicitly disapproved of them yields the following ranking of acceptable behaviors.

Figure Two: Monks' Stated Disapproval of

Monks' Social and Political Activism >Stated Disapproval

The ratio of stated approval to stated disapproval was even more stark, since many monks avoided the more controversial questions by not answering. The top set of activities had more than a 5:1 ratio of "yes's" to "no's". The middle set had ratios from 4:1 to 1:1, and the last set a ratio of 1:2 to 1:8. (The ordering by the lay samples was identical. In particular, the lay samples showed the same pattern of relatively disapproving of "politics", approving of "social service" and expressing ambivalence about monks "speaking as leaders of the Sinhalese race" and "taking a physical role in shramadanas". )

It is interesting to compare these findings with those of Katz (1985). He reports that nine out of ten monks were favorable towards monks "participating in the economic development of the nation" and "in agricultural development". The monks he questioned also strongly (80%) supported monks a."being involved with lay-people beyond temple preaching", b."not restricting their teaching to dharma (religion)", and c."teaching a variety of subjects at universities and other schools". A somewhat smaller majority of three-quarters believed that monks could participate in non-violent demonstrations, and two-thirds believed a monk could organize and lead non-violent demonstration. Many gave the proviso that the satyagraha should not be "partisan/political".[9]

Prof. Katz found a very high (90%) consensus that monks should "advise governments", and two-thirds agreed that monks may "hold appointed offices and positions in a government". Half agreed and half disagreed that monks may "engage in elections and other political activities". Fully two-thirds expressed disagreement with monks "identifying with one or another political party". Katz's findings supported the findings of this paper that most monastic social service activities are approved of by most monks, while partisan politics are in general disapproved of, though a number of activities from both sets occupy intermediate positions, indicating a lack of consensus about these activities in the monastic community.

In general, if any social service activity was felt to be appropriate, most of the rest were felt to be appropriate as well. This allowed the creation of a general measure of "Approval of Monastic Social Service".

Figure Three: Appropriateness of Social Service Activities for Monks

N=72-84

Three questions on the six-question scale of political activities were strongly enough related to one another to merit their use as a scale of "dis/approval for monks' political involvements".[10]

Figure Four: Views on the Appropriateness of Politics for Monks

N=86

Excluding the two ambiguous social-service activities, and the three ambiguous political activities, a continuum of "conservativeness to activism" was created.[11]

Figure Five: Monks' Conservativeness to Activism Continuum

-encouraging lay development activities?

-educating lay people about agriculture or health?

-organizing preschools, shramadanas, etc.?

-organizing lay-owned economic projects in the village?

-setting up temple-based gardens or economic projects?

-engaging in non-violent struggles?

-giving political advice at temple ceremonies?

-as official advisors of the President, MPs?

About 95% of the monks who answered enough of the questions to permit their classification fit the above model. Twenty answered too few questions to permit their classification, and six university monks did not fit the model. The D-school and M-Center samples came out as the most conservative, with only two monks among them on the activist side of the continuum. Sarvodaya's Pathakada trainees and Sarvodaya Sangha Front monks were more moderate, with around two-thirds in the "social-service-oriented bloc", and about a quarter more on the activist side of the continuum. The university monks scored as the most activist (sig.<.05, ANOVA) with fully one-half approving of all the social service activities as well as at least one of the three political activities; six approved of politics to the exclusion of social service. For the leftist university monks, the path of political change was definitely opposed to Sarvodaya's social service model, though most had nothing against social service work itself.

Figure Six: Pro-Sarvodaya Monks' Preference for Social Service and Opposition to Monks' Politics

N=81, both sig<.05

Caste and Sect The M-Center monks were solidly from the Amarapura sect, reflecting the fact that the chief monk there is a chief of that sect. Sarvodaya's Pathakada on the other hand, having been under the guidance of a Ramanna sect chief was disproportionately Ramanna, a sect which accounts for only 20% to 25% of the Sri Lankan Sangha. (This lack of Siyam and Amarapura representation in Sarvodaya's program has been a sensitive issue, and Sarvodaya has gone to some pains to encourage monks from all sects to join in their programs.) The university monks were, on the other hand, statistically more from the upper-caste Siyam sect, reflecting their more advantaged backgrounds and educational opportunities.

In the whole monastic sample, 43 monks identified themselves as Siyam, 33 as Amarapura, 20 as Ramanna and 6 gave "no sect" as their answer. In looking at sect-based differences of opinion however, the most useful distinctions were either Siyam and non-Siyam, or simply between Siyam and Amarapura. Because of monastic history in Sri Lanka, the Siyam Nikaya has been made up solely of upper-caste (goyigama) monks, and has owned the majority of monastic land-holdings. The Siyam sect accounts for half of all Sri Lankan monks, roughly equal to the percent of Sinhalese who are goyigama caste. Amarapura monks, on the other hand, are almost solely from lower-caste backgrounds, while Ramanna monks are from all castes, being distinguished by their disciplinary rigour and relative poverty.[12] Thus, a comparison of Siyam- non-Siyam allows a general gauge of "ruling mainstream" versus "plebian reform" monastics, though the monks themselves rarely acknowledge any such tensions. Siyam-Amarapura comparisons generally measure upper- vs. lower-caste trends with in the Sangha.

The correlations below[13] show that Siyam sect monks tended to believe that ownership of agricultural land by temples was appropriate and that the Sangha had no caste problem, while members of the Amarapura sect tended to believe that there was a caste problem in Sangha. The Amarapura monks also were significantly less cosmopolitan than the Siyam monks (corr=.34, sig<.01).

Figure Seven: Caste, Monastic Sect and Attitudes

N=73

The existence of a political difference between the sects has also been pointed out in a recent paper of Prof. Nathan Katz (1985). Katz conducted a survey and in-depth interviews with 38 monks in the Peredeniya university area outside of Kandy at roughly the same time as the research reported here (late 1983/early 1984). He found for instance that Ramanna monks were more favorable to Buddhist-Marxist synthesis, but less tolerant of other religions, perhaps because Ramanna monks were in the forefront of the fight against Christian missionaries as a part of the anti-colonial struggle. For their part the Amarapura monks (and monks from lower class backgrounds) in Katz's sample were statistically more likely to approve of monks organizing and participating in non-violent satyagraha demonstrations, and of re-instituting the full ordination for nuns.

Some sect-related differences were also found in Hans Wismejer's early 1984 survey of the attitudes of Sarvodaya workers and monks. One of the differences he notes between the monks from different sects was that the only monks who mentioned "gaining political influence in order to help in development" were from the Amarapura sect.

Monks' Sinhala Chauvanism Considering that there was a racial-religious war being fought in the North of the country, and that the role of the Buddhist clergy in encouraging Sinhala extremism had become a pressing national and international issue, two gauges of this attitude were included in the survey. Certainly the issue had important policy implications on Sarvodaya's mobilization of bhikkhus when Sarvodaya was committed to inter-racial harmony: if some Sarvodaya monks were racialist, Sarvodaya is committed to re-educating them, and to recruiting from non-racialist groups.

The two measures of racialism were found to be correlated to one another.

Figure Eight: Monks' Sinhala-Buddhist Chauvanism

N=97

This relationship seems to confirm that only monks who are somewhat racialist themselves would refuse to acknowledge that there are any racialist monks. For instance, in an interview with M-Center's chief, who has gained a reputation as the most staunch Sinhala-Buddhist chauvanist within the respectable monastic elite, I asked what the Venerable thought of the problem of Sinhala extremism among monks. The Thero agitatedly repudiated that there were any extremist monks, insisting that so-called extremist monks merely loved the Sinhala people and felt a responsibility to them, which was different from hating anyone else. His students felt very much the same way, while on the other side of the scale the university bhikkhus felt there were a significant number of extremists.

In Katz's survey, only four of the 38 monks he interviewed disagreed with the statement that "monks should defend the Sinhala-Buddhist identity of the nation", and only six believed that the Tamils had any legitimate grievances. Twenty-eight of the monks, more than two-thirds, ended up in the hard-line category on both questions. Katz then put these two questions together as a factor of Sinhala chauvanism and found, as in the Sarvodaya survey, that the less racist monks tended to be younger, to be university students, to be from the Ramanna sect, to be from lower economic backgrounds and to be in less prestigious professional positions; in other words the monks most exposed to left-wing political education against racialism.

These young, left-wing, anti-racist, rural-plebian or university monks, also tended to approve monks' involvement in party politics and their identification with a political party and to agree with monks standing for elected or appointed office. They were more critical of capitalism and supportive of a planned economy. They were more likely to support the re-introduction of the full ordination for nuns. These left-wing, anti-racist monks' strong support for monks' organizing and leading of Gandhian satyagrahas was in stark contrast to their disapproval of the supposedly Gandhian Sarvodaya movement. In effect, Katz found that the most anti-racist monks were anti-Sarvodaya because of Sarvodaya's political orientation, and that conversely Sarvodaya supporters tended to be more racist. The present survey found the same relationship.

Figure Nine: Pro-Sarvodaya Monks Sinhala Chauvanism

N=92

In Katz's (1985) small study, nine out of ten monks stated that capitalism and Buddhism were incompatible, and that Buddhism was most compatible with democratic socialism (which all the parties in Sri Lanka claim to adhere to). Only one in five expressed support for the post-1977 free market policies, while more than half expressed support for the controlled economy policies of the previous Left government.

For most monks opposition to capitalism is more inspired by feudal-clerical hostility to Western capitalist materialism and secular modernism, than by a Marxist-influenced liberation theology of Buddhism. Many monks who are vocally disturbed by the materialist values being encouraged by tourism, modern media, and the open market are silent about the growing disparity between the advantaged and disadvantaged. Half of Katz's 38 monk sample thought Marxism and Buddhism were incompatible, though a quarter did favor a rapproachment of the two. Those who favored Buddhist-Marxist syncretism tended to be better educated, younger, "well-traveled" and to be members of the Ramanna sect.[14]

The Village Case Studies

VILLAGE A

Village A can be seen as a shining example of Sarvodaya's rural monk leadership model. The bhikkhu there had, in 1974, at the age of 18, left the town temple where he had been ordained and studied, and in which he had familial inheritance rights, to live alone in a small lean-to hut in this extremely isolated, poor and inhospitable village.

The villagers were low-caste people, and all of the forty families, living in a narrow plateau near the top of a mountain, practiced just-barely-above -subsistence rice paddy and slash-and-burn cultivation. They depended for necessities on what extra income their women could bring in from tea work on a nearby estate. Almost all had been born in the village, though some of the youngest mothers had received pre-natal care at the clinic at the foot of the mountain, a two-hour climb down a narrow mountain path. The town beyond the clinic is where the villagers trek every other day to buy those foodstuffs that they can afford, those which aren't already available at one of the three small shops which perch on the path up to Village A. Each household provided meals to the temple on a rotating schedule devised by the monk to spread his burden more equally.

The Maoist JVP had organized in the area since the 60's, and was active there during their '71 insurgency. It was, in fact, the premature attack on the near-by police station that had tipped off the police around the island to the simultaneous attacks on police stations that took place 12 hours later. The local insurgents retreated to caves near Village A for several weeks, and the villagers remember feeding the insurgents, dressing their wounds and lying to the police who came to the village for the first time ever. Eventually the insurgents were arrested without struggle, but the party went underground and continued holding classes until it was re-legalized and its leaders pardoned in 1977. There was a very active chapter in the area when I was there, even though the party had just been banned again. The monk had been approached several times by JVP monk organizers "from the universities" and given copies of the JVP monks' newspaper.

Virtually all the villagers had voted regularly, but some admitted voting with whichever side seemed to be winning in order not to be punished, but rewarded, by the victors. Indeed, it was clear that those villagers who had voted their traditional Left sympathies had helped visit troubles on themselves and their neighbors.

The SLFP Member of Parliament (MP) from the area was ousted in the general rout of the Left in the 1977 polls. His UNP successor, though he had been quite popular as the area's former government agent, had quickly fallen afoul of local sentiments. He had been involved in a much publicized rape case, for which he was censured indirectly by the President. His eventual "acquittal" was viewed with great cynicism.[15]

The MP had become particularly unpopular in Village A because of his punitive attitude, which they believed was motivated by their being a lower caste, and the persistence of SLFP sentiment among the poorer villagers in Village A. After the UNP's 1977 victory, and the souring of the relationship between the village and MP, the MP's first move was to refuse to assign teachers to this hill-top school house, an assignment that had usually been a temporary punishment for a teacher's left-wing politics. At its high-point this school had had five teachers, but now the post-master's brother (with a H.S. education) was teaching upwards of fifty students in grades 1 to 5.[16]

Next came the post-office, which had originally been given to the village by the Left government as a result of the lobbying of the monk and as a political favor to the current post-master, an SLFP activist. The original creation of the post-office had given the new post-master a government job, but had also required him to climb down and back-up the mountain twice a day to fetch the mail, and eventually, in 1976, he succeeded in having the post-office moved to the base of the mountain. The monk strenuously objected to this, since he saw the presence of a post-office as a sign of progress, and convinced the Post-master General to move it back up to the village, infuriating the village post-man. The monk immediately had the villagers move the post-office back up themselves, and told the post-master that missing items would come from his pocket.

So in 1978, after the new UNP-MP decided to revenge himself on the village by canceling the post-office altogether, and with it the post-master's job. The monk was forced to launch a new struggle, eventually writing letters to the President and Prime Minister announcing that he would fast to death if the Post Office was closed. This naturally healed the monk's rift with the post-master. But after the monk's victory the MP was even more spiteful towards the village, and reneged on an election promise of $10,000 dollars for the cutting of their road. [17] This lack of assistance from the government coffer,the source of funds that villages rely on for public works, was a major reason for the village's strong turn toward Sarvodaya for support. Under the previous Left regime a disproportionate number of UNP villages and elites had turned to Sarvodaya when they were isolated and now it was the turn of SLFP villages.

After having organized some village work projects, the monk was introduced to Sarvodaya workers by the local government agent. The Sarvodaya personnel subsequently came and conducted a Ten Basic Needs survey of the village's condition, and held a meeting to discuss the results and to introduce Sarvodaya concepts to the villagers. Shramadanas were planned and groups for youths, mothers, children, elders and farmers were begun. As usual, the mothers' and youths' groups remained the most active, and two girls were nominated from the youth group to do Sarvodaya's preschool training.

At first, shramadanas were held to build a temple directly over-looking the village. This new temple was solid but simple, with a seating capacity of about fifteen people on the packed mud floor, and a bare, plastic-buddha shrine on a rickety old kitchen table. After this was completed, attention was turned to the cutting of a four-mile road from the village down to the road leading into town.

Though the monk had had little success in convincing the villagers of the usefulness of a collective farm he was more successful in encouraging the growth of vegetables, both for consumption and as a cash crop, and in arguing for soil conservation. The previous year the villagers had earned a good deal of extra cash from vegetables, where before they had only grown rice. Tea-picking jobs, however, the other means of earning money for villagers, were also becoming more available as local Tamils were slowly sent back to India under the repatriation agreement.

The monk had opened a community store in the village, operated on a volunteer basis by himself and a "down" shopkeeper's daughter. Profits from the sale of the items, such as soap, pens, tea, and batteries, went to support the shramadana activities. His concern for the village economy extended to a ferocious opposition to village gambling; one story recounts his having rushed an all-night gambling party, swinging his umbrella like a brick bat, chasing one man right up the chimney of the house. He seems more resigned to village men's nightly drinking.

The monk was also the guarantor that the villagers who have gotten drought aid did their obligatory fourteen days a month labor on the road-cutting work, which made it difficult to determine whether he was actually overseeing voluntary "shramadana", or a simple road crew. Certainly his own commitment was evident when he would eat his noon meal in the hot sun on the road watching the work.

The monk was obviously the center of village power and prestige. He was the president of the Sarvodaya society, the Rural Development and Temple Societies, the secretary of the Society for the Preservation of the Sasana (the temple maintenance committee), and the head of the new police-sponsored "Society for the Protection of the Village", in which he attempted to mediate disputes before they required legal intervention. With any problem, spiritual, personal or public, the monk was the first consulted, and the most important decision-maker. In virtually all the interviews the monk got high marks for his asceticism and commitment to their welfare, in contrast to their disparaging remarks for his former colleague who was said to have a disagreeable personality. ("Town priests" were seen as rich and materialistic, though the villagers had actually had little contact with other priests.) Even the youth influenced by the Maoist JVP asserted a strong religiosity. Second to the monk in prestige was the school-teacher, and then the traditional irrigation headman, a handful of respected families, such as the shop-keeper and postman, and the exorcist.

Village B

Village B presented a more ordinary case of village development complexity, though the extent of distaste for their wealthy, decadent and self-involved monk was unusual. Consequently Sarvodaya's work here encountered many more difficulties because it could not rely on the unifying support of a sacralized agent, a monk, but instead was introduced by a secular intellectual, in this case a schoolteacher.

The village sits on the side of a mountain on a rural road south of the former feudal capital, Kandy, with half a dozen wealthy homes on the road itself, and the rest down below on the hillside. The modest temple is on the winding road near the wealthy homes. The current incumbent came from near a major city to this small temple in 1970 when it was under the previous well-loved elder bhikkhu, who died in 1980. The elder monk had done a good deal of social work for the village such as supporting the building of a train platform nearby so that trains to and from Kandy would stop in the village. Though about 70 local children still attend sunday school at the temple, after the elder monk died many of the parisioners began to attend a temple in a village down the road a few miles, mainly because for distaste of the current monk.

After the elder priest died, the current incumbent bought a television (introduced to the country in 1982), a radio and other amenities. He is an addict of the stimulant betel nut, an unsightly habit among some monks which stains the lips a deep purple and swells out the cheeks. The monk is an upper-caste (Goyigama) man of the Siyam sect, attended on by a round, young novice of about 18 years, a 10th grade monastic school graduate who ordained at the age of 10. He is dependent solely on the wealth of the temple and the support of one wealthy woman supporter who lives "on the road".

Though most of the villagers are Goyigama caste, and most have shifted from the SLFP to the UNP, there is some division in the village on the basis of wealth. Some of the villagers live on small plots of tea-estate land that were nationalized and re-distributed under the previous regime, but these grants were influenced by the "political correctness" of the families. Most families still have no land to speak of and get by through share-cropping other people's lands and keeping a cow or two. On the other hand, three of the five families in large homes "up on the road" are large land-owners of share-cropped land. The families owning the land along the road were Burgher, Tamil and Muslim, which gave rise to some racialist resentment among the poor Sinhalese "below the road".

None of the youth from this Goyigama village participated in the 1971 JVP insurgency, though youth from a neighboring low-caste village (with whom this village had had caste-related conflicts) did. Even the two sons of the local constable were imprisoned for seven years. The village population has slowly been increasing through migration, however, and now some of the young people in the poorer areas down near the river below the rail tracks, are sympathetic with the JVP. The local JVP had not apparently pushed an anti-Sarvodaya line, though, and Sarvodaya enjoyed greater support here among the youth than among their elders.

The major problem in this village had always been water. In the 1950's, the government had given a tap water system to the village, but according to the villagers, it had gone to waste because of neglect and the theft of the water taps. Then, in 1980, a school teacher, who is now the chair of the Sarvodaya society and the major Sarvodaya activist in the village, held a meeting of the temple society to introduce Sarvodaya. The Sarvodaya extension workers determined that a new water project would be the ideal thing for this village and drew in the technical aid of a Swiss organization to help build a gravity-water system. Though they held their meeting at the temple, the village monk never gave any support to the organizing, and in fact was a major hindrance to it.

From the beginning the Sarvodaya-activist/teacher encouraged the monk to help with the surveying of village needs, but the monk begged off. ("He was lazy.") When Sarvodaya began work on the water project they began to store the building materials on the temple grounds at the monk's request. Sarvodaya in turn used some of the materials to cement the altar and dug a latrine pit for the temple. But soon the workers noticed materials were disappearing, accused the monk of theft, and moved the materials to another site.

After this, the monk's anti-Sarvodaya feelings became more public. He claimed, on the basis of another monk's experience at Sarvodaya's monastic training center, that Sarvodaya attempts to divide monks between those who do development work (Sarvodaya activists) and those who don't (like himself). In our interview with the monk he felt that it was lazy villagers that discourage monks from getting involved in development work, and insisted that he had held back because there had been opposition to the project among the older more conservative villagers, who he said felt that the condition of the water was fine (though there was a high cholera rate in the village from the drinking of river water).

Conflict between the villagers and the monk continued to grow during the building of the tap system. When the committee was deciding the allocation of tap sites, there was disagreement over whether to put a tap inside the front entrance of the temple near the road. The Sarvodaya committee felt that this tap should be kept available for the use of the local neighbors and for pilgrims. But the monk was adamant that he did not want villagers coming into his compound all the time. Sarvodaya organized a secret vote among the villagers and the monk lost; the tap was placed out on the road. In the process of building this tap one day, a truck accidentally backed into the temple's outside wall, scraping off some lime-white and a chunk of the mud underneath. The Sarvodaya masons offered to repair it, but the monk demanded $500 in reparations, which of course Sarvodaya refused to pay as it represented a significant percent of their total project budget.

Village B's organizational infrastructure is quite meager compared with Village A's. Though the monk remains the official patron of all the voluntary associations in the village, such as the Rural Development Association, the temple patron's committee, the women's society (gov.-sponsored), the Death Aid Society, and even of the Sarvodaya elder's committee, he provides no community leadership because of his reputation as a disagreeable and selfish man. As one village matron put it:

- If the bhikkhus aren't mindful of the peoples' condition and work to help them, then divisions will arise between the bhikkhus and the people.

The teacher, though respected as an educated and sincere man, had enemies in the village who resented the fact that he lived "up on the road" and that he was a newcomer without relations there. He was also the president of the Death Aid society and was the president of the government-sponsored village council until local opposition led to the election of an outsider. He and his children want to move soon because they don't like the neighbors.

Interest in Sarvodaya here seemed more dependent on the material aid that Sarvodaya could bring, than on the strength of community-minded leadership. The shramadanas to help build the water project were not large, and petered out after a while. The elder's committee is the only Sarvodaya committee that still meets; the youth and mothers' groups have become inactive.

The Lay Survey Data

In Village A, the monk helped distribute the surveys himself and made it clear that they were important, resulting in a very high return rate. In Village B, because of the ambivalence of the lay teacher's role, we distributed the surveys, resulting in a much lower rate of return. (There were more serious problems with the methodologically individualist assumptions of survey analysis of the lay samples.[18] These two village samples were compared to each other and to the Sarvodaya workers' and students' samples. Comparing the results of these two villages' surveys, strong differences were found in their approval of monks involvement in village development or politics. These differences in turn seem to have been related to the different dynamics of their monks' leadership roles, which were in turn tied up with their cultural differences.

When the monks and lay people were asked which were better, "village monks" , who teach and are involved with their parisioners, or "forest meditator monks", more than 4 out of 5 believed in the superiority of village monks. When monks and lay people were asked if they believed that "a political party truly committed to rural development could accomplish as much as a movement like Sarvodaya", they said yes 3 to 1.

If there is general agreement that it is good for monks to be involved in their communities, rather than held aloof by fear of impurity, and that politics is as legitimate a way to contribute to the welfare of the community as "non-political" development work, why doesn't this then legitimate politics as a natural vehicle of a monk's social responsibility? According to the dominant Mahavamsist tradition, monks are allowed to take up political activity only when there is "a threat to the Sinhala nation/race/culture". When the villagers aren't directly touched by such a threat, and aren't impressed that the monk's social or political interventions are likely to be in their interests, they are much more comfortable with monks sticking to their religious duties. In those situations where a monk is an "organic intellectual" expressing his village's latent critical consciousness, approval of monks' social and political advocacy may be more forthcoming, and the hegemonic racial-nationalist role even rejected.

For instance, Village B, with their disappointing monk, and the university students with their left anti-clericism, were significantly more opposed to monks participating in any of the social service activities (sig.<.05. anova). Village B was particularly opposed to monks' teaching of Sarvodaya philosophy (sig.<.05 anova), and were also the most opposed to monks participating in non-violent struggles (sig.<.01 anova). The only behavior that the "B" villagers advocated for monks more strenuously than the other three samples was "speaking in the name of the Sinhala race".

The "A" villagers, on the other hand, with their inspired monastic social servant and JVP politicization, were the most opposed to this Sinhala chauvanist role for monks.[19] The militant confrontations of their monk with the government also seems to have influenced "A" villagers; the "A" villagers were the most in favor of monks having official government advisory roles. Their lower caste status was reflected in their insistence that the Sangha had a caste problem (sig.<.01 anova). In short, Village B, with their lack of left politicization and absence of organic intellectual articulation of their critical consciousness stayed strongly within the hegemonic Sinhala chauvanist view of a monk's appropriate social role, and rejected monastic social and political activism, while the radicalized "A" villagers with critical organic intellectual leadership favored monks' leadership and rejected Sinhala chauvanism.

In all the samples, those who agreed with Sarvodaya less, such as the university students, also opposed monks' teaching of Sarvodaya philosophy and tended to believe that Sarvodaya was "political". The university student sample [20] supported Sarvodaya significantly less than the other samples, even though the sample was taken in a sociology class taught by the director of Sarvodaya's Research Institute, students who were presumably more sympathetic with Sarvodaya than most. But the university students weren't rejecting "politics" per se, just Sarvodaya's politics. The university students were, for instance, the least opposed to monks giving political advice to their parisioners at temple ceremonies.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the findings strongly support the thesis of monks' advocacy being determined by organic ties to the peasantry, and of an organic monk as a catalyst of, and tool of, the peasantry's latent critical consciousness. B village's monk obviously was unsuccessful in gaining support or leadership simply on the basis of his being a holy man; though the B villagers had neither been critically politicized by the Left or by their monk, they expressed a critical distaste for their monk and his lack of social concern.

What prior socio-economic or ideological differences must there be in monks who are not attracted to comfortable monastic careers, but who choose poor parishs like the monk in Village A? What was different about the background or structural relations of the late monk of village B who had engaged in social works? Which comes first, public disaffection or lack of organic support? To answer these sorts of questions, larger studies are called for, with more systematic measures of of economic dependency, and of background socio-economic variables, looking at monks' activism before, during and after incumbency in a temple with different amounts of wealth and structural alliances.

Based on the survey of monastic attitudes and the case histories, a tentative model for the types of relationships such as systematic study might find is shown below. Poor family, poor village and low caste origins would make a monk more likely to join the Amarapura and Ramanna sects, and less likely to get a university education. Membership in a more plebian sect would make it more likely that a mok would end up in a poor temple in a poor village, and more likely that he would come into contact with other progressive monks.

Poor villages tend to have Left sentiments, making it more likely that their monk will either acquire such sentiments or have them reinforced. A university education also will make it more likely that a monk will be politically socialized by the Left. Since the Activism continuum was shown to be linear and cumulative, left-wing monks in Sri Lanka also tend to be much more liberal about monks getting involved in social service work, though the reverse is not true.

Poor monks in poor temples in poor villages will tend to advocate the interests of the poor; in other words, the more plebian, the further along the activism continuum we would expect to find the monk. There is curvilinear process at work though, because of the association of Sarvodaya with social service work. Poor villagers, in the absence of government largesse, tend to positive towards Sarvodaya, unless they are being influenced by Leftists who dislike Sarvodaya's conservative politics.

Controlling for Left-ness, I would suspect poor monks to be more pro-Sarvodaya than non-plebian monks. Once monks get involved in Sarvodaya, Sarvodaya endorses social service work and discourages political activism, particularly Left activism. Left monks tend to be less positive about Sarvodaya and hostile to Sinhala chauvanism. In turn, monks attracted to Sarvodaya tend to be more Sinhala chauvanist.

Figure Ten: Factors predicting Sri Lankan Monks' Activism

The irony of the cross-cutting class alliances within the Sangha is that most modern monks with the opportunity to be exposed to cosmopolitan education, such as those at the universities, are also from advantaged backgrounds. Conversely, the plebian clergy, educated in traditional pirivena environments, are the most thoroughly steeped in the Mahavamsist world-view, which patterns their insurgent tendencies. [21] When the plebian clergy are moved by their structural position to become involved in development work or radical politics they tend to be ideologically constrained towards a Sinhala populism, or even fascism; they tend not to be able to develop a "liberation theology", a discourse which grows out of the weaving together of radical cosmopolitan social science and a religious world-view.

Meanwhile the young monks from wealthy and advantaged backgrounds, temporarily proletarianized like all students, follow the student pattern of left-wing protest, which they then tend to abandon when they return to their advantaged temples. University monks who do not come from wealthy temples tend to disrobe to take white-collar jobs, such as teaching; they may remain radical, but they do not tend to remain monks. Unfortunately, it is precisely this confluence of a radical cosmopolitan education/world-view and a plebian structural position which is so rare and so necessary. Organizing monks for progressive social change in Sri Lanka, and probably in other Therevedan Buddhist countries will be very difficult till this problem is addressed.

Appendix One: BHIKKHU DEVELOPMENT SURVEY

This survey is being conducted by the Sarvodaya Research Institute and all individual-level information collected is confidential. When the group statistics and accompanying report are completed, they will be made available from the Sarvodaya Research Institute, Ratmalana. Your cooperation will greatly aid us in improving Sarvodaya's development effort.

1. Where are you currently living?

2. Where were you born?

3. Age?

4. Sex?

5. (for lay) Single, Married?

6. (lay) Number of children?

7. Level of education?

8. (lay)Ethnic group: Sinhala Tamil Muslim Burgher

9. (lay)Religion: Buddhist Hindu Christian Moslem None

10. Occupation?

If Bhikkhu: 10.11 What is your Nikaya? 10.12 Current responsibilities?

10.13 What age ordained?

If Farmer: 10.2 Crops Acreage Ownership

11. Occupation of father?

12. Occupation of mother?

13. Total family income in 1982?

14. When first hear of Sarvodaya? Never, Since '77, '70-'77, before '70

15. Who introduced to Sarvodaya? monk, relative, friend, etc.

16. With Sarvodaya you: disagree strongly, somewhat; agree somewhat, strongly

17. Have you heard of: Dr. Ariyaratne? Ven. Henpitagedera Gnanseeha?

Pathakada Bhikkhu Training Center?

Eksath Bhikkhu Peramuna? Sarvodaya Shanti Sena?

Sarvodaya's National Amity Program?

18. Do you think of Sarvodaya as a political organization?

19. What kinds of political involvement are appropriate for bhikkhus?

19.1 participating in party-affiliated bhikkhu organizations?

19.2 endorsing candidates as individuals?

19.3 engaging in non-violent struggles, i.e. fasts, marches, etc.?

19.4 giving political advice at temple ceremonies?

19.5 speaking as leaders of the Sinhala race?

19.6 acting as official advisors of the President, Parliament, MPs?

20. Has the Sangha encouraged Sinhalese extremism against Tamils?

most bhikkhus, some bhikkhus, no bhikkhus

21. Should temples own farm lands?

22. Do caste problems exist in the Sangha?

23. Youngest age appropriate to ordain shramaneras (novices)?

24. Which is superior? gamavasin (village monks) or vanavasin (forest monks)

25. What political parties are most sympathetic to Buddhism? 25.1 Least sympathetic?

26. What political parties are most sympathetic to Sarvodaya? 26.1 Least sympathetic?

27. Do you think a party committed to rural development, if it came to power, could be as effective as organizations like Sarvodaya?

28. What differences do you see between:

28.1 upcountry and Southern bhikkhus?

28.2 urban and rural bhikkhus?

28.3 university and pirivena-educated bhikkhus?

29. What social service activities are most appropriate for bhikkhus?

29.1 encouraging lay development activities?

29.2 educating lay people about agriculture or health?

29.3 educating lay people about Sarvodaya philosophy?

29.4 organizing preschools, shramadanas, etc.?

29.5 organizing lay-owned economic projects in the village?

29.6 setting up temple-based gardens or economic projects?

29.7 taking a physical role in shramadana?

Appendix Two: Where, and How Many, Monks are there?

A serious defect with any study of the Sri Lankan Sangha is the poverty of available statistical data. The Department of Buddhist Affairs has been registering newly ordained sramaneras (novices) and bhikkhus since the 1930's, though then under the British, under a different name. Unfortunately, since deaths and disrobings have not been recorded it is impossible to to know accurately how many, where, how educated or how old the current body of monks are. Nor do occupational statistics on the national census report on "ecclesiastics", as the British census-takers did until Independence. The following tables have however been drawn together from a variety of sources [22], though considering their varying and questionable methodologies, they should be taken only as guidelines.

Total SL Buddhists Monks as

Census Populat. in Lanka Monks % Bud.s Nuns Temples

1871 2,400,380 1,520,575 NA NA NA NA 1901 3,565,954 2,141,404 7,331 0.34% NA NA 1911 4,106,350 2,474,170 7,774 0.31% NA NA 1921/8 4,448,605 2,769,805 9,666 0.35% 84 6,004 1946 6,657,339 4,294,932 7,095 0.17% 109 NA 1971/5 12,711,143 8,567,570 15,000- 0.18- 413 6,100 18,000 0.21% 6,500 1982 14,850,001 10,292,586 18,000- 0.17- 1500- 8272 25,000 0.24% 3500 A tentative conclusion of Table 1 is that the density of monks as a percent of the Buddhist population had decreased from around 3 1/2 monks per thousand Buddhists before the 1930's, to less than two monks per thousand after the Depression, WWII, and various malaria epidemics. The hardships of this period, and the advancing landlessness and indebtedness of the peasantry undoubtedly made it increasingly difficult to support a non-laboring with the declining agro-surplus.

Another possible explanation would be the rapid expansion of lay intelligentsia into fields such as law, teaching, Western and ayurvedic (native) medicine and the government service, which in turn were dependent on the expansion of educational opportunity and general literacy. Previous to this expansion (and to some degree still today) the majority of monks were encouraged to ordain by parents hoping for "the best" for their little boys. When a monastic career was no longer the best opportunity that was available to these little boys for material, not to mention spiritual, reward and prestige, many of these extraneous motivations began to weaken.

The decline in bhikkhu density can also be seen as part of the general trend of Asian Buddhism in the last century, beginning with the development of "Protestant Buddhism" by (anti-)Western-oriented educated Buddhists and represented most forcefully by the growth of lay Buddhist organizations in many Asian countries.

Bhikkhu density allows an interesting comparison of Lanka and Thailand, both having very similar Therevedan Buddhist cultures, with the major difference being that young Thai men are encouraged to temporarily ordain, while Sri Lankans frown on even sramaneras, much less bhikkhus, disrobing. Many more young Thai men, especially those from the poor North and North-East, join the Thai Sangha as an avenue of material and educational advancement. They can either get their monastic education and leave for a secular career, or work their way through the monastic ranks to Bangkok, with its even greater rewards both through monastic and secular avenues. In 1971, Thailand had about 35 million Buddhists, 185,000 monks and 109,000 novices. This means that Thailand is five times as dense with monks as Sri Lanka: Thailand having 8 1/2 monks, and at least 3 1/2 fully ordained bhikkhus, per thousand Buddhists, and Sri Lanka having at most 2 monks per thousand Buddhists.

Another obvious difference between the cultures has been the impact of colonialism in Sri Lanka, severing the bonds of political and material patronage between the Buddhist State and the Sangha, a patronage which has continued uninterrupted in Thailand, but had to be re-established after a 150 year hiatus in Lanka.

While monks have been declining as a proportion of the population in Sri Lanka, and growing in numbers very slowly, the nuns (dasa sil matas) have seen a spectacular increase. While the monks increased, at best 100% between 1921 and 1982, the nuns have increased 2000% to 4000%. Technically, of course, they are not really nuns since the Bhikkhuni lineage of ordination was never re-established after being broken almost a thousand years ago. Though the nuns in Sri Lanka generally observe the precepts of the full ordination (and are ackowledged as generally more pious than the average monk) their official status is as lay women who have taken the ten lay Buddhist moral precepts. Most have little formal education, live in abject poverty with only the support of small groups of community women.

Table 2: Department of Buddhist Affairs' 1973 figures on registered monks

| District | Temples | Monks | Siyam | Amar. | Rama. | None | Hermitages | Hermits |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colombo | 938 | 3560 | 1736 | 929 | 873 | 22 | 12 | 52 |

| Kalutara | 451 | 1519 | 883 | 470 | 151 | 15 | 10 | 50 |

| Galle | 610 | 2287 | 1147 | 930 | 199 | 11 | 18 | 110 |

| Matara | 418 | 1585 | 942 | 385 | 258 | -- | 20 | 81 |

| Nuw.Eliya | 148 | 447 | 339 | 82 | 25 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Kandy | 658 | 1964 | 1058 | 389 | 508 | 9 | 7 | 13 |

| Kegalle | 454 | 1123 | 797 | 154 | 169 | 3 | 21 | 52 |

| Ratnapura | 361 | 1029 | 352 | 424 | 251 | 2 | 7 | 32 |

| Badulla | 272 | 808 | 364 | 433 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 42 |

| Hambantota | 266 | 833 | 548 | 221 | 64 | -- | 5 | 19 |

| Monaragala | 129 | 367 | 354 | 6 | 7 | -- | 2 | 4 |

| Kurunagala | 939 | 2484 | 1690 | 162 | 620 | 12 | 27 | 49 |

| Puttulam | 154 | 335 | 207 | 99 | 23 | 6 | -- | -- |

| Mannar[23] | 3 | 6 | 4 | -- | 2 | -- | -- | -- |

| A'pura | 267 | 664 | 381 | 77 | 183 | 23 | 4 | 7 |

| Trinco1 | 44 | 99 | 45 | 36 | 17 | -- | -- | -- |

| Vavuniya1 | 12 | 44 | 27 | 17 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Jaffna1 | 3 | 13 | 3 | 10 | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Matale | 229 | 518 | 364 | 66 | 88 | -- | 6 | 20 |

| Pol'ruwa | 99 | 294 | 130 | 119 | 43 | -- | 2 | 39 |

| B'coloa1 | 7 | 12 | 11 | -- | 1 | -- | -- | -- |

| Amparai1 | 48 | 122 | 92 | 22 | 07 | 01 | 05 | 20 |

| Total | 6504 | 20,130 | 11,474 | 5034 | 3514 | 108 | 162 | 560 |

Table 3: Respective Strengths of the Different Nikayas (sects)

Table Three points out several things. The first is that the Siyam Nikaya seems not to be growing, while the other two sects are growing more rapidly. Secondly, as expected, the Siyam Nikaya has a greater number of monks per temple made possible by their greater reliance on temple property and wealth and their greater reliance on wealthy patrons. Third, there are approximately 3 monks per temple and one temple per 1300 Buddhists in Sri Lanka. This is not very dense. Again, Thailand has 12 monks per temple with one temple per 1300 Buddhists (Smith, p. 123).

Footnotes

- ↑ This reclaiming of insurgent religious history was in fact prefigured in Marx and Engels' (1974) insight that pre-capitalist class struggle was expressed as religious heresy and millenial movements: