Hindu-Buddhist Cosmology

The classical cosmologies of India’s own religions, i.e. Hinduism, Jainism and Buddhism, all started to appear after the middle of the first millennium BC. Their roots are, however, much longer and originally emerged from the more simple cosmology of the Vedic period of India (c. 1600–500 BC). The focus here will be on the Hindu and Buddhist cosmologies, since Jainism remained purely an Indian religion, whereas Hinduism and Buddhism also spread to Southeast Asia.

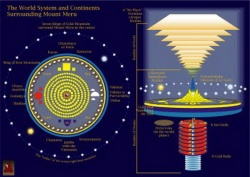

During the centuries from Vedic times to the period of Puranic literature (c. 300–700 AD), and further to the so-called “Medieval” times (c. 600–1500 AD) the cosmologies became increasingly complex. However, the basic structure of the cosmos remained more or less the same. Both Hinduism and Buddhism share the concept of the central axis or the world mountain, Mount Meru in Sanskrit, Sumeru in Pali. This is surrounded by four continents at the four cardinal points, one of them inhabited by humans, and further by circular mountain ranges and seas. The universe, vertically connected by Mount Meru, is divided into three superimposed levels. The underworld and the hells form the lowest level, the world of humans the middle level and that of the heavens the highest. All these levels are, as a rule, divided into several sub-levels.

The cosmologies are not limited only to cosmography, or the geography of the universe. They also refer to the inhabitants of the universe and to the various, more or less, fantastic measurements of space, to the life spans of different creatures, of gods and finally of the whole universe itself. These, as many other details, vary greatly according to different religions, their sects and as different historical periods.

The lowest levels of this hierarchical universe are reserved for sinners and the demons torturing them, as well as asuras, some kinds of anti-gods. Then follow the spheres of animals, humans and semi-gods. At the topmost levels of Hindu cosmology dwell the gods, with Indra as their head, whereas the Buddhist cosmos ends with the level of formlessness. These spheres manifest moral qualities. Through the reincarnation process the Good move up and the Bad move down and consequently the whole universe is ethicised. Though highly generalised, this structure of the tripartite universe and the earth, consisting of four continents centring on Mount Meru, form the basic structure for both the Hindu and the Buddhist cosmologies.

The cosmology is reflected in several ways in the arts. For example, the mandala, a cosmic diagram, in which the sacred centre is surrounded by the four cardinal points, is a two-dimensional adaptation of the concept. On the other hand, Hindu temples with their towers and the Buddhist stupa with its square base and circular body portray the same idea three-dimensionally. Many Asian theatre and dance traditions also reflect this basic cosmology, either in their form or in the mythical characters they depict.