Maudgalyayana

Maudgalyāyana (Pali: Moggallāna; Chinese: 目連; pinyin: Mùlián; Japanese: 目犍連, Mokuren or Mokkenren), also known as Mahā Maudgalyāyana or Mahāmoggallāna, was one of the Śākyamuni Buddha's closest disciples. A contemporary of famous Arhats such as Subhūti, Śāriputra, and Mahākāśyapa, he is considered the second of The Buddha's two foremost disciples (foremost in supernatural powers), together with Śāriputra. He was born in a Brahmin family of Kolita.

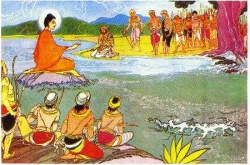

Maudgalyāyana was the most accomplished of all The Buddha's disciples in the various supernormal powers that could be developed through Meditation. These abilities included being able to use Mind-reading for such things as detecting lies from truths, transporting himself from his Body into the various realms of existence, and speaking with Ghosts and Gods. He is traditionally attributed with the ability to do such things as walking through walls, walking on water, flying through the air, and moving with a speed comparable to the speed of Light.

Varying accounts in the Pali Canon show Maudgalyāyana speaking with the deceased in order to explain to them their horrific conditions and give them an understanding of their own Suffering, so that they may be released from it or come to terms with it. Maudgalyāyana was able to use his powers of Mind-reading in order to give good and fitting advice to his students, so they could attain results quickly.

Death: the arhat's karma

Maudgalyāyana's demise came when he was traveling in Magadha. Some accounts put forth that religious cultists stoned him to Death, others say it was robbers. The general consensus is that he was killed in a brutal fashion. When asked why Maudgalyāyana had not protected himself, and why a great Arhat would suffer such a Death, The Buddha said that because Maudgalyāyana had contracted such Karma in a previous Life (he had murdered his parents in a previous Life—one of the Five cardinal sins of Buddhism), so he had no escape from reaping the consequences and had accepted the results. Further, The Buddha stated that even supernormal powers will be of little or no use to oneself in avoiding their Karma, especially when it is so heavy.

Maudgalyāyana in the Mahayana Sutras

The Ullambana Sutra is the main Mahāyāna Sūtra in which Maudgalyāyana is mentioned. The Sutra covers the topic of filial piety, and was a discourse given to Maudgalyāyana by Śākyamuni Buddha. Of particular popularity in Japan, Ullambana is the foundation for Obon, which has striking similarities to Confucian and Neo-Confucian ideals in that it deals with ancestor worship. It is for this reason that the Ullambana Sutra is often subject to Criticism, and has often been called inauthentic because its Confucian leanings are often at odds with other Buddhist teachings.

In the Lotus Sutra Chapter 6 (Bestowal of Prophecy), The Buddha bestows prophecies of Enlightenment on the disciples Mahākāśyapa, Subhūti, Mahākātyāyana, and Mahāmaudgalyāyana.

Source

Maudgalyayana (Skt. Maudgalyāyana; Tib. མོའུ་འགལ་གྱི་བུ་, མཽ་འགལ་གྱི་བུ་, Wyl. mau 'gal gyi bu) — one of the foremost shravaka disciples of Buddha Shakyamuni, renowned especially for his mastery of miraculous powers.

Further Reading

- Nyanaponika Thera, The Great Disciples of the Buddha: Their Lives, Their Works, Their Legacy (Wisdom Publications, 2003).

Source

Mahāmaudgalyāyana. (P. Mahāmoggallāna; T. Mo’u ’gal gyi bu chen po; C. Mohemujianlian/Mulian; J. Makamokkenren/Mokuren; K. Mahamokkŏllyŏn/Mongnyŏn 摩訶目犍連/目 連). An eminent Arhat and one of the two chief disciples of the Buddha, often depicted together with his friend Śāriputra flanking the Buddha. Mahāmaudgalyāyana was considered supreme among the Buddha’s disciples in supranormal powers (Ṛddhi). According to Pāli accounts, where he is called Moggallāna, he was older than the Buddha and born on the same day as Śāriputra (P. Sāriputta). Both he and Śāriputra were sons of wealthy families and were friends from childhood. Once, when witnessing a play, the two friends were overcome with a sense of the impermanence and the vanity of all things and decided to renounce the world as mendicants. They first became disciples of the agnostic Sañjaya Belaṭṭhiputta (Sañjaya Vairāṭīputra), although later they took their leave and wandered the length and breadth of India in search of a teacher. Finding no one who satisfied them, they parted company, promising one another that if one should succeed he would inform the other. Later Śāriputra met the Buddha’s disciple, Assaji (S. Aśvajit), who recited for him a précis of the Buddha’s teachings, the so-called Ye Dharmā verse, which immediately prompted Śāriputra to attain the path of a stream-enterer (Srotaāpanna). He repeated the stanza to Mahāmaudgalyāyana, who likewise immediately became a stream-enterer.

The two friends thereupon resolved to take ordination as disciples of the Buddha and, together with five hundred disciples of their former teacher Sañjaya, proceeded to the Veḷuvana (S. Veṇuvanavihāra) grove where the Buddha was residing. The Buddha ordained the entire group with the formula ehi bhikkhu pabbajjā (“Come forth, monks”; see Ehibhikṣukā), whereupon all five hundred became arhats, except for Śāriputra and Mahāmaudgalyāyana. Mahāmaudgalyāyana attained arhatship seven days after his ordination, while Śāriputra reached the goal one week later. The Buddha declared Śāriputra and Mahāmaudgalyāyana his chief disciples the day they were ordained, noting that they had both strenuously exerted themselves in countless previous lives for this distinction; they appear often as the bodhisattva’s companions in the Jātakas. Śāriputra was chief among the Buddha’s disciples in wisdom, while Mahāmaudgalyāyana was chief in mastery of super normal powers. He could create doppelgängers of himself and transform himself into any shape he desired. He could perform intercelestial travel as easily as a person bends his arm, and the tradition is replete with the tales of his travels, such as flying to the Himālayas to find a medicinal plant to cure the ailing Śāriputra. Mahāmaudgalyāyana said of himself that he could crush Mount Sumeru like a bean and roll up the world like a mat and twirl it like a potter’s wheel. He is described as shaking the heavens of Śakra and Brahmā to dissuade them from their pride, and he often preached to the divinities in their abodes. Mahāmaudgalyāyana could see ghosts (Preta) and other spirits without having to enter into meditative trance as did other meditation masters, and because of his exceptional powers the Buddha instructed him alone to subdue the dangerous Nāga, Nandopananda, whose huge hood had darkened the world.

Mahāmaudgalyāyana’s powers were so immense that during a terrible famine, he offered to turn the earth’s crust over to uncover the ambrosia beneath it; the Buddha wisely discouraged him, saying that such an act would confound creatures. Even so, Mahāmaudgalyāyana’s supranormal powers, unsurpassed in the world, were insufficient to overcome the law of cause and effect and the power of his own former deeds, as the famous tale of his death demonstrates. A group of naked Jaina ascetics resented the fact that the people of the kingdom of Magadha had shifted their allegiance and patronage from them to the Buddha and his followers, and they blamed Mahāmaudgalyāyana, who had reported that, during his celestial and infernal travels, he had observed deceased followers of the Buddha in the heavens and the followers of other teachers in the hells. They hired a group of bandits to assassinate the monk. When he discerned that they were approaching, the eighty-four-year-old monk made his body very tiny and escaped through the keyhole. He eluded them in different ways for six days, hoping to spare them from committing a deed of immediate retribution (Ānantaryakarman) by killing an arhat. On the seventh day, Mahāmaudgalyāyana temporarily lost his supranormal powers, the residual karmic effect of having beaten his blind parents to death in a distant previous lifetime, a crime for which he had previously been reborn in hell. The bandits ultimately beat him mercilessly, until his bones had been smashed to the size of grains of rice. Left for dead, Mahāmaudgalyāyana regained his powers and soared into the air and into the presence of the Buddha, where he paid his final respects and passed into Nirvāṇa at the Buddha’s feet.

Like many of the great arhats, Mahāmaudgalyāyana appears frequently in the Mahāyāna sūtras, sometimes merely listed as a member of the audience, sometimes playing a more significant role. In the Vimalakīrtinirdeśa, he is one of the Śrāvaka disciples who is reluctant to visit Vimalakīrti. In the Saddharmapuṇḍarīkasūtra, he is one of four arhats who understands the parable of the burning house and who rejoices in the teaching of the one vehicle (Ekayāna); later in the sūtra, the Buddha prophesies his eventual attainment of buddhahood. Mahāmaudgalyāyana is additionally famous in East Asian Buddhism for his role in the apocryphal Yulanben Jing. The text describes his efforts to save his mother from the tortures of her rebirth as a ghost (preta). Mahāmaudgalyāyana (C. Mulian) is able to use his supranormal powers to visit his mother in the realm of ghosts, but the food that he offers her immediately bursts into flames. The Buddha explains that it is impossible for the living to make offerings directly to the dead; instead, one should make offerings to the Saṃgha in a bowl, and the power of their meditative practices will be able to save one’s ancestors and loved ones from rebirths in the unfortunate realms (Durgati).

Source

The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism by Robert E. Buswell Jr. and Donald S. Lopez Jr.}