Buddhist images and art

There are four main types of images found in Buddhist temples, each conveying a different level of being in Buddhist cosmology:

- 1) images of The Buddha;

- 2) images of Bodhisattvas;

- 3) images of Deities, Spirits, heavenly beings, and guardian God; and sometimes

- 4) images of kings of Wisdom and Light that serve as Protectors of Buddhism.

Most Buddhist Art consists of depictions of Buddha, usually in statue from and to lesser extent in murals, frescoes and other paintings. The way in which Buddha is depicted often says more about the culture that created it than About Buddhism itself.

There are lots of symbols and codes in Buddhist Art. Simple things like hand positions and the shape of the arms can convey symbolic meaning. Western viewers often have a hard time making sense of it all because they have little exposure to the symbols.

For about five centuries after Buddha's Death, it was forbidden to produce images of The Buddha. During that time various devices such as set of large footprints or a treelike post with three Dharma wheels were used to represent The Buddha without actually showing him. The Buddha and his early Disciples opposed the personalization of The Buddha’s message and discouraged speculation about their existence after they were dead. The Buddha hoped that his followers would find salvation though Meditation, not through the worship of images. That didn’t stop millions of images of The Buddha and Bodhisattvas from being created though. If he were alive today The Buddha would no Doubt be appalled by the number of images of him that have been raised around the globe.

Early Buddhist Art

There is no Buddhist Art that dates back to period when Buddha was alive nor is there any from and the centuries that followed. The oldest Buddhist Art is in the Form of symbols—such as the Wheel of Dharma, Stupas and the tree of Enlightenment—not human. Objects and images that indicated signs or “traces” of Buddha presence—such as footprints, parasols or empty seats—were the most common.

The first images of Buddha appeared in the A.D. 1st, 2nd and 3rd centuries in Gandara, a region in what is now northern Pakistan, and Mathura, near Agra and Delhi in northern India. Among the oldest know images of Buddha are sandstone seated Buddhas carved in India in the A.D. 1st or 2nd century with a friendly, inviting face. Gandara Art includes Persian Influences, Greek Influences, introduced by Alexander the Great, and West Asian Influences.

A typical Gandara piece consists of a multi-image sculpture with a central image of Buddha surrounded by images from his Life. The Hair, clothing and posture all show Greco-Roman Influences. Youthful Buddhas often had their Hair arranged in wavy curls and wore toga-like garments like these found in Roman statues. Around the same time more Indian-like images were created in Mathura which featured bodies expanded by sacred Breath and clad in robes that left one shoulder bare. In southern India and Sri Lanka Buddhas with serious faces and heavy build were being created

Buddhas created in the Gupta period in northern India, from the 4th to 6th century, had an “ideal image” and featured a downward glance, Spiritual aura, Hair arranged in tiny curls, and a sensuous Body visible beneath a transparent robe. These became the models for future images created by artists in India, Nepal, Thailand and Indonesia.

Many of the early works from India have Hindu Influences such as multiple arms and heads as well as hand, arm and leg positions that are reminiscent of those found on sculptures of Hindu Gods and Indian dancers.

Buddha Images

Perhaps because The Buddha put so much emphasis on self-denial no images of him were made for some time after his Death. When images were made they were not true likenesses. Instead they were highly stylized and symbolic with features like long era lobes, stretched by earrings, a sign of royal birth; Wheel-shaped marks on the soles of his feet, reminders that his ministry had started the Wheel of Truth spinning.

Traditionally, Buddhist artists have sought to depict one of 12 episodes of Buddha’s Life: 1) his prior existence in Tusita Heaven; 2) his conception; 3) his birth 4) his education; 5) his marriage; 6) his Renunciation; 7) his period of asceticism; 8) meditating under the Bodhi tree; 9) the defeat of Mara; 10) his Enlightenment; 11) his first sermon; and 12) his Death. Some of these episodes are depicted more often in paintings than in sculpture.

Statues Buddha is nearly always depict Buddha in one of half dozen or so position. The most common position shows a sitting Buddha with one hand raised (the sermon position). The second most common one shows The Buddha sitting with one hand on top of the other (the Meditation position). The reclining Buddha symbolizes the sage in "an attitude of entering Nirvana" and depicts The Buddha at the moment he leaves his earthly Body and achieves the state of Nirvana, or Enlightenment. The standing Buddha is rare. He is Thought to represents The Buddha as a teacher or perhaps giving a Blessing.

Common Buddha images found in Japanese Buddhist temples include 1) Sakyamuni (the historical Buddha), recognizable by one hand raised in a praying gesture; 2)Yakushi (the Healing Buddha), with one hand raised in the praying gesture and the other holding a vial of medicine; 3) Amitabha (The Buddha of Infinite Light and Buddha of The Western Paradise), sitting down with the knuckles together in a Meditative position; 4) Dainichi (the Cosmic Buddha), usually portrayed in princely Clothes, with one hand clasped around a raised a finger on the other hand (a sexual gesture indicating the unity of being); and Maitreya (Buddha of the Future).

Buddhist Art often contains a central image of Buddha surrounded by numerous other images, which can include scenes from Buddha Life, different manifestations of Buddha, different Bodhisattvas and Deities. Bodhisattvas often appear on either side of The Buddha. They are often distinguishable by their more human-like appearance; serene smiles which represent Joy and Compassion.; and a top knot of Hair or a headpiece, sometimes with smaller figures in the crown. Some images of Buddha are accompanied by images of Buddha's first two disciples, young Ananda and old Kasyapa.

Present, Past and Future Buddha Images

Sakya Thukpa (Sakaymuni) is the historical Buddha, who lived in Nepal in the 5th century B.C. He has blue Hair and a Halo of Enlightenment around his head. He is always depicted in a sitting position, with his legs crossed in the Lotus position and has 32 marks on his Body, including a dot between his Eyes, the Wheel of Law on the soles of his feet, and bump on the top of his head. Manifesting the “witness” Mudra, he holds a begging bowl in his left hand and touches the Earth with his right hand. He is often flanked by two Bodhisattvas. [The name before the parenthesis is Tibetan, the name in parenthesis is Sanskrit]

Marmedze (Dipamkara) is the Past Buddha. He preceded the historical Buddha and spent 100,000 years on Earth. His hands are pictured in the “protection” Mudra and he is often pictured with the Present and Future Buddha.

Jampa (Maitreya) is the Future Buddha. He is currently in the Form of a Bodhisattva and is waiting for his chance to return to Earth, 4000 years after the Death of Sakaymuni. He is usually seated, with a scarf around his waist, his legs hanging down and his hands by his chest in the turning of the Wheel of Law

Amitabha Opagme (Amitabha) is The Buddha of Infinite Light. He resides in the “Pure land of the west,” where he looks after people on their journey to Nirvana, and is regarded as the original being from which the Panchen Lama was reincarnated. He is red. His hands are held together on his lap with a begging bowl in the “Meditation” Mudra.

Dhyani Buddhas, or the five Contemplation Buddhas—Amitabha (red), Vairocana, Akshobhya (white), Ratnasambhava (yellow) and Amoghasiddhi (green) —are major focuses of Meditation. Also known as the five Jinas (eminent ones), or dhyani-Buddha, they control the different regions of paradise where Buddhists may be reborn. Each is a different color and has different symbols and mudras associated with it.

Tsepame (Amitayus) is The Buddha of Longevity. Like Opagme, he is red and his hands are pictured in the “Meditation” Mudra, but he holds a vase containing the nectar of immortality. The Medicine Buddha (Menlha) holds a medicine bowl in his left hand and herbs in his right hand. He is often depicted in a group of eight Buddhas.

These Buddhas have different manifestations. The many-headed Hevajra is a wrathful manifestation of Akshobhya (the Imperturbable Buddha). Symbolizing the transformation of the poisons such as Anger, he is often depicted in an embrace with his consort Nairatmya. Their passionate embrace represents the Enlightened state that come from the union of Wisdom and Compassion. Hevajra is often shown stomping his own image, showing the defeat of egoism.

Buddha Footprints

Carved footprints called buddhapada are among the oldest-known works of Buddhist Art and Faith, with the oldest examples from the A.D. 1st century Gandhara in Pakistan. One such piece carved in grey stone has a pair of Truth wheels on each meter-long foot. Smaller ones have been carved on lapis lazuli seals less then two centimeters in length.

Footprints of The Buddha are important objects of veneration, both in terms of purported footprints left behind by the historical Buddha and representations of his footprints. Because they seem to convey his presence without him actually being there footprints have came to represent transcendental Power.

Footprints are both representations of The Buddha’s presence and absence, and loss and recovery. They are images that are easy to identify with. In ancient times, footprints and hand prints were regarded as the physical touch of Buddha and other major religious figures. The Buddha himself said, “Creatures without feet have Love, / And likewise those that have two feet / And those that have four feet I Love, / And those, too, that have many feet.”

A footprint was chosen as representative of The Buddha because it expressed humility and addressed the fear that his image might be worshiped. On footprints, The Buddha is reported to have said: “In the future, intelligent being will see the scriptures and understand. Those of less intelligence will wonder whether The Buddha appeared in the World. In order to remove the doubts. I have set my footprints in stone.”

Carved footprints was supposed to be imprinted with 108 auspicious symbols. The hand or palm of The Buddha is an important Symbol. In Tibet, footprints and to a lesser degree handprints of revered lamas appear on thangkas. They are often placed next to the subject’s patron Deity or an image of the Lama himself. The handprints often look like handprints in prehistoric Caves or the ones at Grauman’s Chinese Theater.

Mudras and Buddha Image Symbols

There are many symbolic gestures and objects found on images of The Buddha that have important meanings. A raised hand means no fear. Curly Hair, elongated ears and hands with Eyes are symbols of Wisdom. Bare feet and Monks cloak represents asceticism. Often The Buddha has a nimbus or Halo around his head, expressing Enlightenment. When The Buddha touches the ground it is a sign of Compassion.

Among the 32 signs of a “superman” ( mahopurusha ) are: 1) a Wisdom bump ( ushnisha ), a cranial bump covered by top knot of Hair representing omniscience, also associated with ancient Indian wandering Ascetics; 2) a small tuft of Hair ( urna ), or dot between the eyebrows, symbolizing Renunciation. Other superman signs include elongated ears, antelope-like legs, skin so smooth that dust doesn’t collect on it, intensely black Eyes, cow-like eyelashes, 40 teeth, sheath-cloaked genitals, raised palm (the boon-granting gesture), and long and straight toes.

Each of the episodes of Buddha’s Life have their own distinctive symbols. After The Buddha achieved Enlightenment, for example, he was surrounded by a six-Lord aura that was 20 feet in diameter. After he meditated for another several weeks his aura was invaded by the serpent king Mucalinda, who. opened its hood and wound its coils seven times around The Buddha to protect him from a rain storm.

The hands are in stylized poses called mudras . They include the 1) the Meditative pose, with cupped hands resting on the lap; 2) the protection pose, with the right hand raised; 3) the teaching pose, with one hand raised and the index finger touching the thumb of the same hand. 4) If a Buddha holds a Wheel of Dharma in his left hand and a scripture in the right hand its signifies he is a good teacher. 5) Touching the ground symbolizes a call to Mother Earth to witness his defeat of Mara as well as Compassion.

Buddha of Medicine holds a medicine box in his left hand and makes a Devil-expelling gesture with his right hand. Symbolic objects found on Bodhisattvas and Deities include swords used to cut down disruptive passions and Desires; cords used to pull wayward people back to the correct Path.

Buddhist Sculpture and Painting

There are more statues of Buddha in the World than of any one else. Some scholars claim that the idea of making Buddha statues was introduced to Asia from Europe. The earliest images of Buddha had Greco-Roman Influences. In many of the early depictions, Buddha resembled Apollo.

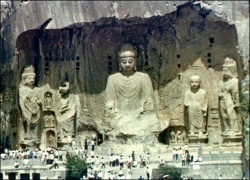

Most of the really old Art works found in Asia are Buddhist sculptures. More sculptures remain than paintings because more sculptures were probably made and paintings tend to deteriorate with time. Buddhist sculptures are generally made from wood or bronze. Some are gilt. Buddha images, whatever conditions they are in, are considered sacred. Climbing on them, and in some cultures, photographing them is considered disrespectful.

beginning in the third century Caves in China, India and Southeast Asia were decorated with British frescoes a long with statues. Large Monasteries sometimes contain hundreds and even thousands of frescoes and paintings of Buddha, Bodhisattvas and Buddhist Gods such as Avalokitesvara. Many of the frescoes depict episode from Buddha's Life and they are used to educate the illiterate masses the same way many Christian churches educate followers with scenes from the lives of Christ, Mary and the saints.

Paintings are often regarded as religious objects and sometimes used as Meditation aids. Smithsonian Japanese Art curator James Ulak wrote, "In every instance the artist attempted to create, through a single painting or an ensemble of paintings, an environment or moment of visual impact that complemented the Faith of the viewer, enhanced a belief, and infused everyday Life with a sense of transcendence."

Avalokitesvara (meaning “Lord Who Looks Down”) is arguably the most common and popular Buddhist celestial being. Regarded as a God, a Goddess and a Bodhisattva and featured prominently in the Lotus Sutra, he is closely associated with Amitabha and lives between births in Amitabha’s Western paradise.

Avalokitesvara has a number of Body parts and objects with symbolic meaning. Of his 11 heads, the central head one at the top belongs to Amitabha. He often has multiple arms, sometimes more than a thousand of them. The central pair of hands is in the cupped position representing respect. In one hand he hold a Lotus, symbolizing Enlightenment, In another he holds a bow and arrow, symbolizing a Bodhisattva’s ability to get at the Heart of the matter.

Avalokitesvara appears in 33 different manifestations and 108 forms, including the Goddess of mercy, popular with pregnant mothers and invoked by people in trouble. Simply repeating her name several times is considered enough to drive away Evil.

Tibetan Buddhist Bodhisattva Images

Jampelyang (Manjushri) is the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. He is regarded as the first divine teacher of Buddhist Thought and is sort of a patron saint for school children. In his right hand is a flaming sword that cuts Ignorance. His left, in the “teaching” Mudra, cradles a half-opened Lotus blossom. He is often yellow and has blue Hair or a crown.

Drolma (Tara) is a female Bodhisattva with 21 different manifestations. Known as the saviouress, she was born from a tear of Compassion shed by Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara)and considered a female version of Chenresig and a protectress of the Tibetan people. She symbolizes purity and fertility and is believed to be able to fulfill wishes.

Drolma is often picturesdin a longevity triad with the red Tsepame (Amitayus) and the three-faced, eight-armed female Namgyelma (Vijaya). In her green manifestation Drolma sits in a half Lotus position on a Lotus flower. In her white manifestation she sits in a the full Lotus position and has seven Eyes, including ones on her forehead, both palms, and both soles of her feet.

Guardian King Dhritarastra Chokyoing (Lokpalas) are the Four Guardian Kings. Often found at the entrance hallway of Monasteries and believed to be Mongolian in origin, they protect the four cardinal directions. The eastern king is white and carries a lute. The southern king is blue and carries a sword. The western king is red and carries a thunderbolt. The northern king is yellow and carries a banner of victory and a jewel-spitting mongoose. He is regarded as the God of Wealth and is depicted riding a Snow Lion.

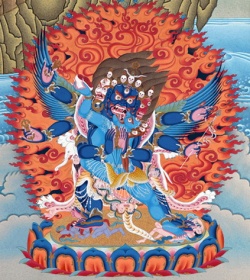

Dorje Jigje (Yamantaka) is the most well-known protector of the Yellow Hat sect. Known as the destroyer of Yama, the Lord of Death, he is a blue, beastly-looking creature with eight heads, one of which is the head of a bull, and strings of skulls around his waist and neck. He holds a flaying knife and a skull cup in his eight to 36 arms. With his 16 feet he stomps on eight Hindu Gods, eight mammals and eight birds. Dorje Jigje punishes Evil people to a Life in Hell, helps guide good people to a better Rebirth and crushes earthly passions that block Enlightenment. Yamanataka is so horrible that no one should look at his image, especially women. Statues of him are often covered.

Yamantaka Nagpo Chenpo (Mahakala) is wrathful Tantric God and a manifestation of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara). Associated with the Hindu God Shiva, he is blue and has fanged teeth, a crown fo skulls, and carries a trident and skull cup. He comes in various forms, with two to six arms and is regarded as the protector of tents by nomads. Nangpo Chenpo means the Great Black One .

Tamdrin (Hahagriva) is another wrathful manifestation of Chenresig (Avalokiteshvara). Associated with the Hindu God Vishnu, he is red with a white face on the right and green gace on the left and has a Horse’s head in his Hair, a crown of skulls, a tiger skin around his waist and a garland of 52 chopped off heads. On his back are the wings of Garuda. In his six hands are a Lotus, club sword, skull cup, snare and ax. Under his four legs a sun disc and corpses. Tandrin in red and Dorje in blue often serve as guardian Gods at the entrance of temples.

More Tibetan Buddhist Protector Deities

Mahakala Chan Dorje (Vajrapani) is the wrathful Bodhisattva of Energy. He is blue with a tiger skin around his waist and snake around his neck. In his right hand is a thunderbolt, the Symbol of the Tantric Faith. Chan Dorje means “thunderbolt in hand.”

Demchok (Chakrasamvara) is a meditational Deity with a blue Body, 12 arms, four faces, and a crescent moon in his topnot. In his hands are a thunderbolt, a Bell, a elephant skin, an axe, a hooked knife, a trident, a skull, a hand drum, a skull cup, a lasso and head of Brahma. He wears a tiger skin and has a garland with 52 severed heads around his neck.

Palden Lhamo (Shri Devi) is the guardian of Lhasa, the Dalai Lama an the Yellow Hat sect. An angry manifestation of Tara The female counterpart of Nagpo Chenpo (Mahakala), she is blue, wears tiger skin and human skin Clothes and has earrings made of a snake and a lion and carries a skull cup full of blood in her left hand and a club in her right hand. A moon is in her Hair; the sun is her stomach; and a corpse is in her mouth.

The walls or entrances of Buddhist Monasteries and pagodas are often decorated with "Wheels of Life," paintings representing principals of Buddhism. They are complex, image-filled paintings that aim to show viewers how Desire imprisons us in a World of Suffering and Rebirth and that the Mind is only a Delusion.

The three cardinal sins—passion and Delusion (represented by a cock), hatred (a snake), and Greed and stupidity (a pig)—are often situated at the center of the Wheel. The Wheel is turned by Yama, the Lord of Death, who represents the limitations of existence. At the bottom of the Wheel are hot and cold hells and a scale used to measure Good and bad Karma one has accumulated in one’s lifetime.

In the ring outside the center are the 8 or 12 Karma formations, which contain the victims of bad Karma (black background) on the left and the beneficiaries of good Karma (white background) on the right. In the next ring are the six spheres of existence; then the twelve links in the chain of causation, culminating in the search for Truth; and finally in the outer most ring are symbols depicting Impermanence or Death.

The six spheres of existence are; 1) the realm of the Gods, a transitory place where Happiness rises above Suffering; 2) the realm of the Asuras (jealous Gods), where creatures of all sorts fight over fruit on the wishing tree and have to be reminded by Buddha to stay on the Path; 3) the realm of the Pretas (the Hungry ghosts), the home of grotesque figures who have given into Greed and can’t eat because their throats are too narrow; 4) the hells, where creatures with cold hearts and Anger live in misery; 5) the realm of the Animals, a place of Ignorance, lethargy and apathy; and 6) the realm of the humans, characterized by birth, old age, disease, sickness and Death.

The twelve links in the chain of causation features: 1) a blind woman (symbolizing Ignorance); 2) a potter (Unconscious of will); 3) a monkey (Consciousness); 4) men in a boat (self-Consciousness); 5) house (the five senses); 6) lovers (Attachment); 7) a man with an arrow in his Eye (Feeling); 9) people drinking (Desire); 10) a figure grasping fruit from a tree (Greed); 11) pregnancy (birth); and 12) a man with a corpse (Death).

The Wheel of law or the Wheel of Dharma represents Dharma, the cosmos and the concept of Karma. The central Wheel is symbolic of Buddha’s teachings which set the Wheel of Dharma in motion.

Buddhist Artists

Most works of Buddhist Art have no signature or other identifying mark.

Robert Beer, an artist and expert on Tibetan painting, told a Thai newspaper, “If you lose the need for individual expression, you’ll become more open to a tradition itself. So it’s more a process of evolving, and it’s very humbling in a sense because you lose your self importance of being a famous artist...so that everyone is essentially becoming part of the tradition itself, losing that need to become an artist, to understand, to be a personality.”

Beer also said, “As you work on a drawing, you would think, ‘Why is she wearing this? Then through that you begin to understand Buddhist concepts because they are encapsulated in the images—why the Deities have six arms, four arms, eight arms.”

Tibetan Art Mandalas, See Separate Article under Art in Tibet Under China

Buddhist Art in China, See Separate Article under Art in China

Buddhist Art in Japan, See Separate Article under Art in Japan

Source

by Jeffrey Hays

factsanddetails.com