Quantum Mechanics and Compassion: Parallels and Problems

Anthony Damiani often showed us how a good problem or question can be more valuable than a good answer. My own inner experience along with nearly four decades of academic teaching and research confirms that perspective, whether in theoretical physics, Buddhism, or the psychology of C.G. Jung, focusing on sources of confusion always drives me into fertile territory and creative possibilities. I approach this chapter in that spirit. The exploration begins with a fundamental principle in quantum mechanics and ends with a remarkable development of a parallel principle in Tibetan Buddhism. I never argue that quantum mechanics in any way proves the truths of Buddhism. Rather, I am considering a deep similarity in their respective approaches to indistinguishability, the establishment of it through exchange, and the consequences that flow from it. This similarity forces me to confront my selfishness and wrestle with the demand for universal compassion that arises from the Tibetan Buddhist version of indistinguishability. My approach through a physics and Buddhism parallel offers a unique perspective on compassion, the other great pillar alongside of emptiness upon which Tibetan Buddhism stands.

Uniqueness and indistinguishability in physics

As a child, I loved the game of marbles. My pockets often bulged and rattled with brightly colored glass spheres. A circle drawn in the dirt with marbles placed in it, knuckles on the ground with a marble tucked into the pocket in front of my thumbnail, and off we go blasting marbles out of the circle. I had a wicked shot. We all had our favorite “shooter” and preferred certain colors and designs of marbles to others. Imagine putting ten marbles into a box and then vigorously shaking it. The marbles bounce off each other and the walls of the box in complicated ways. Nevertheless, thanks to their differing colors and designs, we know that each marble has a unique identity. We also know that each particle has a welldefined trajectory in the box, no matter how complex the motion or how many marbles are in the box. Therefore, if we filmed the marbles as they bounced around in the box, we could easily distinguish cases in which the marbles were exchanged. For example, we would have no trouble distinguishing the film in which the red marble starts in the left corner and the black marble starts in the right corner from the film in which the starting positions of the red and black marbles were exchanged. However, the situation is entirely different in quantum mechanics.

The simplest system showing how different things are in quantum mechanics is a box containing two electrons. (You could also use protons, neutrons, or whatever elementary particles you like, as long as they are of the same kind.) With marbles in the back of our minds, we imagine a little number “1” engraved on one electron and a number “2” engraved on the other— signifying the unique identity of the electrons. Of course, you cannot engrave electrons, but they do have different physical properties. A minimal description of these properties must consider the particle’s location and quantum mechanical spin. (Quantum mechanical spin has no exact macroscopic analogue, but we can approximate it by thinking of the spin of a top or wheel that rotates with constant speed. Although the value of the quantum mechanical spin does not change, its orientation relative to a designated set of coordinate axes does.) With our experience with marbles in mind, we assume that the physical property set uniquely defines the electron, giving it a welldefined identity. Furthermore, we imagine that it is possible to follow the path of particles 1 and 2 inside the box, tracing out their separate trajectories. However, our experience with marbles has led us astray here.

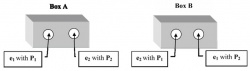

In contrast to marbles, electrons or other elementary particles do not have welldefined trajectories despite the continuous evolution of the system. Even more important for my present purposes, the two electrons are completely indistinguishable. That is, mathematically exchanging properties for particle 1 with those of particle 2 leads to no discernable change in the system, no measurable differences. Although the mathematical exchange of particle properties is clearly defined, it results in no measurable differences. We have a clear conceptual difference (mathematical exchange of properties) without empirical or measurable consequences. From the point of view of macroscopic experience, this indistinguisability established through exchange in quantum mechanics is a very strange idea. Yet, it is an absolutely fundamental principle. So it is worth stating the physics more precisely. In box A, place electron, e1, with welldefined properties or attributes, P1 (P1 must minimally contain a specification of the location and spin of the electron). Let electron, e2, have properties, P2. Now in box B exchange the properties so that P1 becomes P2 and P2 becomes P1 (see Figure 1 below). No measurements of any kind on boxes A and B can distinguish any differences between these boxes. In short, indistinguishability of quantum particles means that exchanging particle properties has no measurable effect.

Whether we have a box with two or two trillion electrons in it, we have the erroneous tendency to believe that each electron has a welldefined or unique identity, an essence or self- nature, a sort of “serial number” stamped on it. In fact, as particle exchanges reveals, all of the electrons in a given system are completely indistinguishable—without an essence or self-nature. Furthermore, the indistinguishable particles do not have welldefined paths or trajectories and yet the system evolves continuously from one state to the next. As we will see in later chapters, here is the typical situation in quantum mechanics where we have continuity without self-nature, continuous evolution of the system without any unique or independently existing essence to the objects undergoing the evolution. The next chapter has a remarkable Buddhist reflection of this principle. There we will see how the Middle Way appreciates the unique nature of each individual and their continuity without there being any inherent self-nature of persons or things. For example, there is a continuity of personal karma or action, and you will become a unique Buddha, but all this without there being any unique self of persons or inherently existing identity. This is a subtle view that combines uniqueness within a thoroughgoing denial of inherent nature of persons. As we will see in several chapters of this book, continuity without a unique identity or self-nature is a core principle within both the Middle Way and quantum mechanics.

The indistinguishability of quantum particles is one of the most fundamental properties of matter. It is a radical departure from classical or Newtonian physics and ordinary experience, where we take for granted the unique identity of the individual elements of our experience whether they be marbles or people. To see how radical a departure this is from our conventional views consider the following simple thought experiment. Imagine that we are in a big auditorium with a thousand people. You and I are sitting next to each other. If we exchange seats, could a camera mounted in the ceiling detect any difference in the room? The camera could take two photographs, one before we switched seats and one after. These photos could be compared with a computer and the differences would easily show up. Even beyond the physical identity detected by a camera, we have an instinctive belief in our unique identity or individual self, something beyond the camera’s reach. The emptiness doctrine, discussed in the following chapter, denies this unique identity or self, while acknowledging a conventional identity enshrined in the identification in our wallet. (Recall that the negative formulation of emptiness asserts that all persons and things lack independent or inherent existence, while the positive formulation asserts that phenomena only exist through their interdependence or relatedness.)

In striking contrast to our experience in the auditorium, if you had 1000 electrons in a system and exchanged the property sets of any two particles there would be no measurable change of any kind. This complete indistinguishability means that there is no individual identity for any of the particles. They are all the same in a deep sense, beyond anything we experience in the macroscopic realm. In other words, each elementary particle is completely empty of a self nature or they have no inherent existence. Yet, they still function to make atoms, molecules, and the material world within which we live. The indistinguishability of particles of a given type in a well-defined system is an essential building stone in the foundation of quantum mechanics. It applies to the earliest moments of the big bang and the farthest galaxies. With just a couple of lines of mathematics, this quantum indistinguishability leads directly to the famous Pauli Exclusion Principle, which says that no two electrons in the same system can occupy the same quantum state. The Pauli Principle accounts for the stability of the matter making up our bodies and the rest of the universe. It also accounts for the detailed spectra of atoms and the structure of the periodic table of the elements. It should be kept in mind that for macroscopic systems with large numbers of particles most quantum effects disappear. Nevertheless, for a given system, one that can be approximately isolated from the rest of the universe, the particles of a given type are indistinguishable, independent of their number.

It fills me with wonder to think that the extraordinary multiplicity and diversity seen all around us springs from a sea of indistinguishable elementary particles, entities without a unique identity or self. For the next section, try to keep in the forefront of your mind that there is an intimate connection between exchange of particle properties and indistinguishability. In fact, in quantum mechanics, the lack of measurable differences after exchange establishes indistinguishability, gives us our working definition of what we mean by it, and allows us to draw farreaching conclusions from indistinguishability. Next, I explore how indistinguishability is realized through exchange in Tibetan Buddhism and see what vital principle flows from it.

Indistinguishability in Tibetan Buddhism

I am sitting on the porch of my favorite café, sipping coffee and reading a book. I occasionally look up and watch people coming and going. I never tire of savoring the uniqueness of each individual—all those different sizes, shapes, colors, ways of moving, and unique psychologies. What a delight! There has never been anybody exactly like the reader or writer of this sentence. Starting from the big bang and continuing to the death of the universe, there will never be another person exactly like you. For this reason, each person’s path to Buddhahood must also be unique. The uniqueness of our path is one reason for the importance of having a guru or lama who can provide individual instruction. Despite our extraordinary uniqueness, which on the conventional level is never in dispute, there are fundamental ways in which we are all alike. In fact, being dazzled by the uniqueness and multiplicity all around us, there is a real danger that we will fail to appreciate in what ways we are indistinguishable. Tibetan Buddhism never tires of telling us that everyone desires happiness and freedom from suffering. Yes, you are certainly different from me in innumerable, important ways. However, in that both of us desire happiness and freedom from suffering, we are totally indistinguishable. There are of course other ways in which we are alike, but none more fundamental nor important than our common desire for happiness and freedom from suffering and our equal right to such happiness. In analogy with physics, if we exchanged any two people and could measure their desire for happiness and freedom from suffering, and their right to such happiness, we would find no measurable differences between the states before or after the exchange. Please remember that Buddhism affirms our conventional identity, enshrined in our passport number,but also emphasizes our fundamental indistinguishability in that we all desire happiness and freedom from suffering, and have an equal right to such happiness. Here I explore some implications of our indistinguishability.

This type of indistinguishable nature is obvious for most of us. For Americans it has a special resonance because our Declaration of Independence tell us, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.” Although this self-evident truth in the Declaration is not fully upheld and there are differences between it and the Tibetan view of our indistinguishable natures, the fundamental point is the same. Being such an obvious truth, we are in danger of trivializing it or considering it true merely by definition. As we will see, agreeing with Tibetan Buddhism that such indistinguishability of persons is a fundamental truth leads to some powerful implications, at least as significant as the Pauli Exclusion Principle. Our common desire for happiness and freedom from suffering is easy to appreciate in the case of our family and loved ones. However, if it is universally true it must cut across all our likes, dislikes, national boundaries, historical eras, and so forth. For example, even the most hated person or evil tyrant also desires happiness and freedom from suffering. Whether Attila the Hun, a terrorist bomber, or Mother Teresa of Calcutta, we are all the same in this sense. In Tibetan Buddhism, this level of indistinguishability is at least as important as the indistinguisha- bility of particles in quantum mechanics because it is the foundation for universal compassion. Universal compassion, the heart of Tibetan Buddhism, is the sincere desire for the welfare of all sentient beings along with the will to act on this desire. Being universal, it extends way beyond the little circle of our loved ones. In the face of this indistinguishability and its logical conse- quence of compassion, it is rationally indefensible to act selfishly, to put our needs before those of another. The Dalai Lama tells us,

- Whether people are beautiful and friendly or unattractive and disruptive, ultimately they are human beings, just like oneself. Like oneself, they want happiness and do not want suffering. Furthermore, their right to overcome suffering and be happy is equal to one's own. Now, when

you recognize that all beings are equal in both their desire for happiness and their right to obtain it, you automatically feel empathy and closeness for them. Through accustoming your mind to this sense of universal altruism, you develop a feeling of responsibility for others: the wish to help them actively overcome their problems. Nor is this wish selective; it applies equally to all.[1]

Unfortunately, I am not completely ruled by reason or logic. My self-cherishing, my egotism, overwhelms my understanding of our indistinguishable desire for happiness and freedom from suffering. Yet, all the great Tibetan teachers tell us that our self-love, our continuous concern for our ego and its desires, is actually the greatest impediment to our happiness, while love and concern for others is the greatest source of joy and satisfaction. For example, Shantideva, the eighth-century Indian adept and one of the brightest lights in the firmament of Tibetan Buddhism, tells us:

- Whatever joy there is in this world

- All comes from desiring others to be happy,

- And whatever suffering there is in this world

- All comes from desiring myself to be happy.[2]

For all these years, I had it all wrong. I thought the more attention I paid to my desires and material comforts the happier I would be. Yet, even now that I have some understanding and experience of Shantideva’s wisdom, it is not fully a part of my being. I am not always able to actualize this knowledge in my everyday activity. Knowing this, Shantideva gives special exercises that help us overcome our selfishness and realize our fundamental indistinguishability. He wrote,

- Thus whoever wishes to quickly afford protection

- To both himself and other beings

- Should practice that holy secret:

- The exchanging of self for others.[3]

So, just as in quantum mechanics, to establish or realize indistinguishability we must engage in exchange. Unfortunately, “that holy secret: the exchanging of self for others,” is much more difficult than exchanging elementary particle properties. The mathematics necessary to exchange particle properties is simple and, of course, it helps that emotionally we do not care which particle is which. We simply do not identify with electrons or protons. However, we have spent innumerable incarnations identifying with an ego and its associated body, believing it to be real or independently existent, and focusing on satisfying its insatiable desires. This identification or self-grasping, the false belief in an independently existent ego, immediately gives rise to self-cherishing or egotism. This process is so ingrained, so immediate, that exchanging our self-love for love of another is extremely difficult. Despite this difficulty, we can realize indistinguishability in both physics and Tibetan Buddhism through the procedure of exchange. To help us with the more difficult exchange in Buddhism, Shantideva gives us a powerful exercise with detailed instructions on just how to manipulate our imagination. The exercise takes the follow- ing form.

Generally, we break up humanity into three groups: those people that we believe are inferior to us, those that we believe are equal to us, and therefore rivals, and finally those that we believe are superior to us. The basis for this grouping—whether spiritual attainment, education, money, or other criteria–varies from one person to the next. However, the threefold grouping nevertheless occurs. We feel haughty toward our inferiors in the first group, competitive toward our equals in the second, and envious of our superiors in the third. In this exercise, we take the point of view of somebody in the group we believe to be inferior to us. We imaginatively exchange identities with that inferior person. We assume their point of view as much as possible, then gaze back at ourselves through their eyes with envy and criticize ourselves from their point of view. Let me give an example that would be appropriate for a professor. In our example, the professor thinks very highly of himself, his developed intellect, his ability to articulate and manipulate ideas, and so forth. Let us say he frequently deals with a secretary who gives him some trouble. Of course, he secretly believes that secretaries are a lesser form of life. Then implementing Shantideva’s exercise, our professor imaginatively takes on the secretary’s identity and writes out something like,

- I have so much work. I can never get caught up and he (the professor) just keeps dumping it on my desk and complaining that I’m not fast enough. He’s never satisfied with either the quality or quantity of my work. I’m always so tense when I have to leave early to take care of one of my children when they’re ill or have to go to a doctor. On top of it all, he often makes disparaging remarks about women. But I need to pay my bills and must do my best with this job. He went to all those fancy schools and has had all the advantages that I never had. He’s arrogant,self-centered, and swollen with his own self-importance. He never takes the slightest notice of my needs or appreciates anything I do. Despite all his education and academic honors, he knows nothing about simple kindness.

Of course, such a hopeless professor is unlikely to do this exercise, but I trust you get the general idea. Although Shantideva does not tell us to write out such an exchange, I find writing makes the experience much more concrete and powerful than just doing it entirely in the imagination. When I lectured on material from this chapter at Namgyal Monastery in Ithaca, NY, the head resident teacher there, Lharampa Geshe Thupten Kunkhen, agreed that writing it out was a good idea. After doing so, you can then take it into your meditation and further deepen the ex- perience. In Shantideva’s description of the imaginative exercise he uses “I” for the person believed inferior and “he” for the practitioner of this exercise (you and me). Taking on the identity of the inferior person, we are to say:

- “He is honored, but I am not;

- I have not found wealth such as he.

- He is praised, but I am despised;

- He is happy, but I suffer.”

- “I have to do all the work

- While he remains comfortably at rest.

- He is renowned as great in this work, but I as inferior

- With no good qualities at all.”[4]

(Unfortunately, this whining sounds like me on a bad day!) Shantideva then wants us to criticize our self from the point of view of this inferior person. For example, the inferior one criticizes our lack of compassion by saying,

- “With no compassion for the beings

- Who dwell in the poisonous mouth of evil realms,

- Externally he is proud of his good qualities

- And wishes to put down the wise.”[5]

In essence then, Shantideva is asking us to vividly take the point of view of somebody we feel is inferior to us and, from this position, generate jealousy and criticism toward ourselves. Depending upon whom you consider your inferior, you modify the exact words to generate the necessary jealousy and criticism toward yourself. Next, we take the viewpoint of somebody we consider our equal or rival. From that person’s viewpoint, we generate intense competitiveness and criticize ourselves from our rival’s point of view.

Finally, we take the point of view of somebody we believe is our superior and, from that position, make some withering criticisms of our self, and promise to deny ourselves happiness. It is not clear how this person is truly superior when he says about us:

- “Even though he has some possessions,

- If he is working for me,

- I shall give him just enough to live on

- And by force I’ll take (the rest).”

- “His happiness and comfort will decline

- And I shall always cause him harm,

- For hundreds of times in this cycle of rebirth

- He has caused harm to me.”[6]

In quantum mechanics we switch particle properties, while in this exercise we switch our self-cherishing or our self-love from its usual location in our body-mind complex to a new location in somebody we believe is inferior, equal, or superior to ourselves. From these three differing viewpoints, we generate intense jealousy, competitiveness, and haughtiness. Then we criticize ourselves from these three viewpoints. By doing this exercise with concentration and vividness we learn to take the other person’s point of view. We thereby reduce our intense identification with our own point of view and actually make the exchange of self with other. Along with refining our personality, we decrease our false sense that we inherently or independently exist— the root of all our suffering, as the Tibetans never tire of telling us. I encourage you to take a few minutes, identify a person in each of the three groups, and write out an example of the exercise. It may not be entertaining, but it is transformative. As the excellent commentary on Shantideva’s text, Meaningful to Behold by Geshe Kelsang Gyatso tells us,

- The main purpose of such meditative techniques is to stabilize and increase our actual ability to exchange self for others and thereby destroy our self-cherishing. From such an ex change, an unusually strong mind of great compassion emerges and from this, we develop an unusually strong bodhichitta motivation [the altruistic desire for enlightenment for the sake of all sentient beings]. In fact, the bodhichitta developed by this approach is generally more powerful than that cultivated in the sevenfold cause and effect meditation [discussed in an earlier chapter].”[7]

It is important to notice that by exchanging our identity for that of the other person, the negative states such as jealousy, haughtiness, or criticism are directed at ourselves. In contrast, if we directed these negative states at another person this would be a form of black magic—the opposite of bodhisattva activity. (The bodhisattva ideal is to seek liberation to be maximally effective in relieving suffering for all sentient beings.) If our concentration is strong, such directed negative thought would harm the other person. However, even if our concentration is weak, such activity would certainly harm us. In Shantideva’s exercise, a vivid manipulation of our imagination replaces the mathematical manipulations in quantum mechanics. Rather than mathematically exchanging particle properties to reveal the indistinguishability between particles, here we imaginatively exchange our self-cherishing and viewpoint with another to realize our fundamental indistinguishability. Through repeated use of this exercise, we can actually learn to exchange self with other and thereby directly experience our fundamental indistinguishability—that everyone desires happiness and freedom from suffering. Then, despite individual differences among us, this indistinguishability becomes a living reality that transforms our world and us. Just as critically important properties of matter arise from quantum indistinguishability, genuine bodhichitta arises from our human indistinguishability. Effective use of the exercise of exchanging self with other can transform an unfelt and ineffective truth into one that powerfully guides our every action. In this way, the Tibetans unite love and knowledge.

The obligations of compassion

Let us say that through exchanging self with other, the truth of our indistinguishability becomes a living reality, not just a parroted slogan. If despite our obvious differences, we truly realize that in terms of wanting happiness and freedom from suffering we are as indistinguishable from each other as elementary particles are, that the truth is just as universal as indistinguishability is in physics, that it applies to all persons from the earliest moments of human history to the present moment, then heavy obligations fall on us. How then can I continue to live a life of luxury when there is so much suffering in the world? How can I rationalize my material indulgences when there are so many who go to bed hungry every night? For example, the most recent report available shows that in 2002 more than 840 million people in the world are undernourished—799 million of them are from the developing world. More than 153 million of them are under the age of five.[8] (For comparison, there are 300 million people in the United States, about 4.6% of the world’s total.)

In contrast, 67 percent of US citizens aged twenty and above are overweight and 32 percent are obese, according to the 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey from the U.S. Center for Disease Control.[9] Given these facts, how can I hold to the indistinguishability of every human and still rationalize my selfish use of resources? An analysis by the internationally known philosopher and ethicist, Peter Singer,[10] provides a particularly vivid formulation of this moral problem. I follow Singer and begin the analysis with a little story. There is a shallow pond on the Colgate campus with geese, ducks, and beautiful landscaping. One day I am walking past the pond on my way to my Tibet class and I notice that a little girl has fallen into the water and is drowning. I jump into the pond and pull her out. Of course, my muddy cloths force me to go home and change them and thereby miss class, but everybody agrees that I did the right thing. If there were other people near the pond who just ignored the girl’s drowning, that would not absolve me of my responsibility to help her. After going home and changing my clothes, I return to my office. I check my mail and notice an appeal from Oxfam International. They are soliciting funds for food relief for the masses of people starving in Darfur, Sudan. I feel swamped by requests for aid of all kinds. My regular bills are piling up and I am saving money for a new car. I throw the request into the recycling bin. Everybody understands my plight. Nobody condemns me.

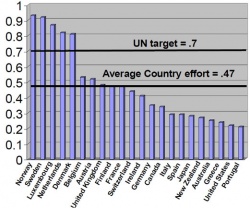

But wait, don’t the starving people in Darfur want happiness and freedom from suffering just as much as the little drowning girl? Is my compassion only local and not universal— extending to just those physically near me or my loved ones? Today when news and images of Darfur are just a mouse click away, am I only obliged to help the little drowning girl and not starving Africans? When a few mouse clicks will take $100 from my credit card and efficiently turn it into sustenance for hungry Africans, is spending the same money at a fancy restaurant morally neutral? I am not alone in my refusal to help the less fortunate abroad, to act on the realization that indistinguishability extends way beyond my little circle of loved ones. For example, averaging over the years 2002 to 2005, the United States is the member of the Development Assistance Committee that gives the smallest fraction of its Gross National Income (GNI) for Official Development Assistance (ODA) or what used to be called foreign aid. Figure 2 below displays the most recent percentage of ODA to GNI by country[11] for 2005 and shows that the United States is now second from the bottom. This modest improvement is largely through debt relief and aid to war-torn Iraq and Afghanistan, not increases in ODA to the neediest. Since the United States’ “war on terror” and related foreign policy initiatives are responsible for the increase in ODA, the true situation is worse than even the dramatic graph reveals. There are many complexities surrounding ODA, which I cannot discuss here. The sad point is that “rich countries give less than half the amount of aid they gave in the early 1960s when they were far less affluent.”[12] It pains me as an American to examine Figure 2 and see how poorly the United States compares to the 21 other countries in the DAC. The pain of all this is intensified through practicing exchanging self with other and getting a little taste of the indistinguishability I share with everybody, including those starving in Africa.

This yawning divide between rich and poor is a worldwide problem that has doubled in the last decade. Former World Bank president, James Wolfensohn, tells us:

- Today you have 20 percent of the world controlling 80 percent of the gross domestic product. You've got a $30 trillion economy and $24 trillion of it in the developed countries. The income of the top 20 is 37 times the income of the bottom 20, and it has doubled in the last decade. These inequities cannot exist.[13]

In the face of these inequalities, Peter Singer formulates our responsibility when he writes,

- My next point is this: if it is in our power to prevent something bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought, morally, to do it. By "without sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance," I mean without causing anything else comparably bad to happen, or doing something that is wrong in itself, or failing to promote some moral good, comparable in significance to the bad thing that we can prevent. This principle seems almost as uncontroversial as the last one [suffering and death from lack of food, shelter, and medical care are bad]. It requires us only to prevent what is bad, and to promote what is good, and it requires this of us only when we can do it without sacrificing anything that is, from the moral point of view, comparably important.[14]

Singer compresses and slightly qualifies his statement by saying, “if it is in our power to prevent something very bad from happening, without thereby sacrificing anything morally significant, we ought, morally, to do it.” He points out some of the consequences of his reasoning saying,

- The uncontroversial appearance of the principle just stated is deceptive. If it were acted upon, even in its qualified form, our lives, our society, and our world would be fundamentally changed. For the principle takes, firstly, no account of proximity or distance. It makes no moral difference whether the person I can help is a neighbor's child ten yards from me or a Bengali whose name I shall never know, ten thousand miles away. Secondly, the principle makes no distinction between cases in which I am the only person who could possibly do anything and cases in which I am just one among millions in the same position.

If we accept the truth of our indistinguishability, that everyone desires happiness and freedom from suffering, these conclusions follow with remorseless logic. However, when I presented this argument to students in my Tibet class, they argued that is it different when the person is drowning or hungry right in front of you. Your obligation is obvious and much more

compelling then when it is at a distance. Despite being proficient users of the Internet, proximity in terms of mouse clicks is not the same for them as physical proximity. However, a universal principle such as the indistinguishable nature of electrons must apply in the big bang and in a distant galaxy just as it does in my own body, from my birth to my death. In the same way, our common desire for happiness and freedom from suffering, must apply at all times and places. Otherwise, it is not a universal principle. Singer is certainly clear about this. Perhaps spending so many years in physics dealing with universal principles and appreciating how they must always apply in all cases intensifies my problem. If I accept our human indistinguishability as a universal principle, it leaves me nowhere to hide from its moral demands. Nor is there anywhere to hide from the realization of how far I fall short of the bodhisattva ideal. Yes, as Professor Lars English of Dickinson College reminds me, a Buddhist believes that prayer and teaching Buddhism, not just sharing material wealth, are important forms of expressing the bodhisattva ideal. However, as the quotation below shows, although the Dalai Lama prays fervently for the welfare of all sentient beings and teaches ceaselessly, he believes material help is also required. His Holiness certainly knows the demands of our indistinguishability. He writes,

- I feel strongly that luxurious living is inappropriate, so much so that I must admit that whenever I stay in a comfortable hotel and see others eating and drinking expensively while outside there are people who do not even have anywhere to spend the night, I feel greatly disturbed.

It reinforces my feeling that I am no different from either the rich or the poor. We are the same in wanting happiness and not to suffer. And we have an equal right to that happiness. As a result, I feel that if I were to see a workers' demonstration going by, I would certainly join in. And yet, of course, the person who is saying these things is one of those enjoying the comforts of the hotel. Indeed, I must go further. It is also true that I possess several valuable wristwatches. And while I sometimes feel that if I were to sell them I could perhaps build some huts for the poor, so far I have not. In the same way, I do feel that if I were to observe a strictly vegetarian diet not only would I be setting a better example, but I would also be helping to save innocent animals' lives. Again, so far I have not and therefore must admit a discrepancy between my principles and my practice in certain areas. At the same time, I do not believe everyone can or should be like Mahatma Gandhi and live the life of a poor peasant. Such dedication is wonderful and greatly to be admired. But the watchword is “As much as we can”—without going to extremes.[15]

Here we see the Dalai Lama’s deep commitment to our indistinguishable nature, to our equal right to happiness and freedom from suffering. However, given that even the Dalai Lama, the bodhisattva of compassion, admits “a discrepancy between my principles and my practice in certain areas,” where does this leave those of us struggling against our selfishness to develop bodhichitta? Sadly, I do not have an answer, only the awareness of my shortcomings and a resolve to improve. That resolve partly expresses itself, not without hesitation and doubt, in me giving all royalties from this book to Oxfam and other agencies that work to relieve human suffering.

Footnotes

- ↑ Tenzin Gyatso, The Compassionate Life (London, UK: Wisdom Publications, 2001) pp. 21-2.

- ↑ Shantideva, A Guide to the Bodhisattva’s Way of Life translated by Stephen Batchelor (Dharamsala, India: Library of Tibetan Works & Archives, 1979) p. 120.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 119.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 122.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 123.

- ↑ Ibid. p. 122.

- ↑ Kelsang Gyatso, Meaningful to Behold (London, Tharpa Publications, 1986) p. 276.

- ↑ State of Food Insecurity in the World 2002. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.http://www.fao.org/docrep/005/y7352e/y7352e00.htm.

- ↑ www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/overwt.htm.

- ↑ Peter Singer, “Famine, affluence, and morality,” Philosophy & Public Affairs 1 (1972) pp. 229-243; “The Drowning Child and the Expanding Circle,” New Internationalist, 289, April 1997. These along with many other inspiring articles are available at www.PeterSingerLinks.com.

- ↑ The Global Policy Forum website describes itself as, “A non-profit, tax-exempt organization, with consultative status at the United Nations. Founded in 1993 by an international group of concerned citizens, GPF works with partners around the world to strengthen international law and create a more equitable and sustainable global society.” Data for the graphic comes from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and is posted at: globalpolicy.igc.org/socecon/develop/oda/tables/aidbydonor.htm.

- ↑ The Global Policy Forum website provides much data and analysis of ODA and related issues. The quotation was taken from the report found at globalpolicy.igc.org/socecon/develop/oda/2005/08stingysamaritans.htm.

- ↑ Roger Cohen, "Growing Up and Getting Practical since Seattle", New York Times, September 24, 2000, sec. 4, p. 16.

- ↑ Singer, 1972, p. 230.

- ↑ Tenzin Gyatso. Ancient Wisdom, Modern World: Ethics for the New Millennium (London, Abacus, 2001) pp. 183-4.