Buddhism 101 – Questions and Answers

The young Venerable Khai Thien

Buddhism 101 – Questions and Answers

(A Handbook for Buddhists)

Foreword

Dear Friends in Dharma,

This handbook, Buddhism 101—Questions and Answers, is a selected collection of Buddhist basic teachings for beginners. While composing this book, we thought in particular about those Buddhists who just initiatively started to study and practice Buddhism in environments of multiple religions and multiple cultures. Therefore, the basic themes introduced here serve to provide readers with a general view of the Buddha’s teachings in regard to both theory and practice. Given the limitations of a handbook, we dare not go further into intensive issues of Buddhist philosophy as doing so may lead to difficulties for beginners. However, the selected questions discussed here are the core teachings of Buddhism. As a beginner, you need to master these teachings firmly and precisely before going further into the Buddhist studies. We hope that this handbook will be a useful ladder to help you along the way in your learning and practicing.

Los Angeles, Spring 2009

Ven. Khai Thien, Ph.D.

101 – Questions and Answers

1. What common feature does Buddhism share with other religions?

2. What is the difference between Buddhism and other religions?

3. What is a brief history of the Buddha?

4. What is the essential characteristic of Buddhism?

5. Does Buddhism advocate for renunciation of the world?

6. Is Buddhism a religion or philosophy?

7. What is the essential tenet of Buddhism?

8. If Buddhism is a non-theistic religion, can we say that it is a religion of science or one of philosophy?

9. If Buddhism already had, from the beginning, its establishment for the path of enlightenment and liberation, why did such concepts as the Great vehicle (Mahāyāna) and Small vehicle (Hīnayāna) subsequently arise in its history?

10. How does the original form of Buddhism differ from its development?

11. In addition to the two forms of Buddhism—origin and development—why do we have the names Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

12. Regarding practical activities, is there any difference between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

13. Regarding the process of enlightenment, is there any difference between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

14. Can you explain more about the ten stages of Mahāyāna Bodhisattva development?

15. Regarding the Buddhist ideal model for practitioners, is there any difference between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

16. How many major systems of philosophy exist in Buddhism?

17. What is the fundamental belief in Buddhism?

18. What is the karmic law of causes and effects?

19. What are the three karmas?

20. What does Samsāra mean in Buddhism and how does it work?

21. If Buddhism does not believe in an immortal soul, then what and who will be reborn in the cycle of samsāra?

22. How can one know that he or she will be reborn in the cycle of samsāra?

23. Buddhist mental formations include such concepts as the mind, thought, and consciousness. How different are they?

24. If there is no existence of God, then on what condition is the existence of heaven and hell based?

25. If all comes from the mind, can a non-Buddhist practice the Buddhist doctrine?

26. What is the primary core of spiritual practice in Buddhism?

27. Is there any difference in the manner of practice of Buddhism and that of other religions?

28. Does one benefit if he practices just one of the three pure studies: moral discipline, meditation, or wisdom?

29. How can a person become a Buddhist?

30. Why must a person take refuge in the Triple Jewels to become a Buddhist?

31. Can a person attain enlightenment and liberation if he just practices the Dharma without taking refuge?

32. Is the moral discipline of Buddhism similar to or different from that of other religions?

33. What are the four all-embracing virtues (Catuh-samgraha-vastu)?

34. What are the deeds of pāramita (transcendental perfection)?

35. What is the Bodhi mind (Bodhicitta)?

36. What are the four foundations of mindfulness?

37. What are the four right efforts (catvāri prahāṇāni)?

38. What are the four supernatural powers (rddhipāda)?

39. What are the five spiritual faculties (pañcānām indriyāṇām) and their five powers (pañcānāṃ balānām)?

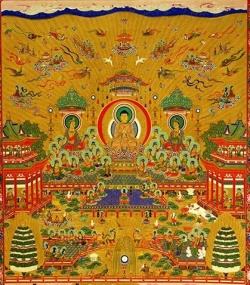

40. What are the seven branches of enlightenment (saptabodhyanga)?

41. What is the noble eightfold path?

42. Is there any plain and simple teaching that can be remembered most easily?

43. Why do we eat vegetarian foods?

44. Can a person become a Buddha by eating purely vegetarian foods, and how is vegetarianism related to spiritual practice?

45. Does a Buddhist break the precept of not killing when he eats meat?

46. What does repentance (Ksamayati) mean in Buddhist rites?

47. Can a person’s unwholesome karmas be eradicated through repentance?

48. What is the aim of reciting the Buddhas’ names?

49. Would you please explain more about the doctrine of Pure Land School (Sukhāvati) and the practice of reciting the Buddhas’ names?

50. What is the core teaching of the Pure Land School?

51. What is meditation?

52. How is Ānāpānasati meditation related to vipassanā meditation?

53. What are the main themes of both Ānāpānasati and vipassanā meditation?

54. Regarding the breaths and breathing, how important are they in the practice of meditation?

55. Would you please explain more about the role and function of the one-pointed mind in meditation?

56. How do feelings relate to the mind?

57. Would you please explain more about insight meditation?

58. Why does a practitioner have to mediate on the body in such detail?

59. What are the five aggregates?

60. Why are the five aggregates considered the foundation for the twelve senses-bases and eighteen psychophysical domains?

61. Why are aggregates, senses-bases, and psychophysical domains analyzed in such detail?

62. Would you please explain the nature of the self or ego in the Buddhist view?

63. If there is no individual self or personal ego, who will suffer and who will be happy?

64. What is non-self?

65. Does the reality of the non-self relate to nirvāna?

66. How can one perceive the meaning of emptiness (śūnyatā) in the presence of things?

67. Why is it said that the middle way is the path leading to nirvāna?

68. How can we apply the teaching of the middle way to practical life?

69. Would you please explain more about the two truths?

70. Is the absolute truth identical to the realm of nirvāna?

71. Would you please explain more about the characteristics of nirvāna?

72. Why does a Buddhist expression say that “samsāra is nirvāna”?

73. What does nirvāna relate to in the doctrine of three Dharma Seals?

74. How can an ordinary person live a life of non-self?

75. How should a selfish and egocentric person practice the Dharma?

76. Would you please explain the concept of “merit” in Buddhism?

77. What is the characteristic of ‘pure merit’ and that of ‘impure merit’?

78. What is the Buddhist view on the issue of “good and evil”?

79. Why are there different viewpoints on the issue of “good and evil”?

80. What is ignorance in the Buddhist view and is a wise person like a scientist still ignorant?

81. How should a person of weighty ignorance practice the Dharma?

82. How should a person of weighty hatred (ill will) practice the Dharma?

83. How should a person of weighty craving practice the Dharma?

84. How does the Buddhist concept of happiness differ from the mundane concept of happiness?

85. What is the true career of a Buddhist?

86. Do different methods of spiritual practice oppose one another?

87. Is there any difference in the methods of practice for young and old persons?

88. How should an aged person practice the Dharma, particularly when his or her time of life is shortened?

89. Why should a person be aware of the future life if he or she practices being in the present?

90. How should young people practice the Dharma?

91. How should a person who is experiencing much illness or who is near death practice Dharma?

92. What should one do in order to extinguish his or her fear of death?

93. Loneliness is an obsession of a person when facing old age and death. How should one practice Dharma in order to overcome this obsession?

94. How can a person overcome this obsession of old age and death if he or she is unable to appreciate the taste of inner tranquility?

95. How should we encourage our younger children to practice the Dharma?

96. How can we live in harmony with a person who follows other religions in the same family?

97. How should we live in harmony with a person of divergent views?

98. How can we live in harmony with a person who embraces the wrong views?

99. How can one live peacefully with or alongside a person who is gossipy and stubborn?

100. What should one do in order to make the inner life peaceful?

101. How should a Buddhist practice when facing suffering?

- 1. What common feature does Buddhism share with other religions?

Buddhism shares numerous common features with all other religions. All religions encourage human beings to do good deeds, avoid evil deeds, cultivate a life of morality and compassion, and develop human dignity for both oneself and others as well as for family and society.

- 2. What is the difference between Buddhism and other religions?

The key point in which Buddhism differs from other religions is that Buddhism does not believe in the existence of a Personal God who creates, controls, and governs the life of all sentient beings, including human beings. According to the Buddhist view, suffering or happiness is created not by God, but by each individual person together with the karmic force, which is also the product of each person. The Buddha taught that a person becomes noble or servile not because of his or her origin (e.g., family background or social rank), but because of his or her own actions. Indeed, personal action makes a man or woman noble or servile. In addition, radical differences exist in the teaching of Buddhism and that of other religions. Buddhism considers all dharmas (things or existences, including both the mental and the physical) in this world to be conditional and exist in the mode of Dependent Origination. No dharma can exist independently and permanently as an immortal and invariable entity. Thus, all existences are non-self. Similarly, no one—either human or non-human—is able to control and govern the life of another person, only the person him- or herself. Consequently, the most essential point in Buddhist humanistic teaching is that all sentient beings have their own Buddhahood; thus, each person has the ability to become a Buddha. Enlightenment and liberation, in the Buddhist view, are equal truths for all sentient beings, not a holy privilege reserved particularly for a certain person. This great view of equality in Buddhist doctrine is rarely found in any other religion.

- 3. What is a brief history of the Buddha?

Buddhism was established in India by the Sakyamuni Buddha more than 2,600 years ago. Modern historians believe the Buddha was born in Lumbini Park, Nepal, during the Vesak (May) full moon Poya day around the sixth century before the Christian era. The Buddha, whose birth name was Siddhartha, was born a prince and the only son of King Suddhodana and Queen Mahamaya. Upon growing up, he married princess Yasodhara, and they had a son named Rahula. After deeply realizing the nature of human suffering from birth, old age, sickness, and death, prince Siddhartha decided to leave the palace to look for the truth of enlightenment and spiritual liberation. Working through five years of study with several masters and six years of solitude engaging in ascetic practice in the forests, he finally attained enlightenment under the bodhi tree after forty-nine days of motionless meditation. Since this enlightenment, he has been called the Buddha, a person who has reached enlightenment and has been liberated from the cycle of samsāra. After attaining enlightenment, he started to teach the Dharma (the path leading to enlightenment and liberation) and established the Sangha (a community of monastic people such as monks and nuns) over a period of forty-five years. He entered Nirvāna (passed away) at the age of eighty under the twin Sala trees at Kusinara, around 543 B.C.E.

- 4. What is the essential characteristic of Buddhism?

Traditionally, Buddhism is defined as the path leading to enlightenment, as Buddha means an awakened person or enlightened person. Thus, the essential characteristic of Buddhism, as the term expresses, is the path to enlightenment and liberation from the world of samsāra.

- 5. Does Buddhism advocate for renunciation of the world?

This question requires a delicate answer. History tells us that the middle-aged Buddha Sakyamuni attained enlightenment and ultimate liberation from the binding cycle of samsāra. However, he remained with the world for more than forty years to teach the Dharma and bring benefits to all sentient beings. Thus, two important points should be considered:

a) The Buddhist concept of enlightenment (bodhi): The term bodhi in Buddhism refers to a full awakening or full awareness of the operation of pratītyasamutpāda, the Law of Dependent Origination, the mental and physical corporeality on which the life of a human being is developed. Based upon this capability of full awareness, the individual is able to overcome all afflictions, delusions, and impurities and create a true life of peace and happiness. In addition, the capability of awareness is, in reality, divided into various levels from low to high; therefore, you should keep in mind that spending a whole life practicing the Dharma does not always mean that you will obtain full awareness (realization of the absolute truth). Although you have the ability to become enlightened, your level of enlightenment always depends on your individual karmic force, which is a personal current of mental cohesion of your own lives in the past.

b) The Buddhist concept of liberation (moksha): Literally, the term moksha or mukti in Sanskrit means release, transcend beyond, or liberate from the bondage of samsāra. Thus, liberation in Buddhism also consists of various levels, from simplicity to absolute freedom. Whenever you transcend beyond the bondages of afflictions and defilements such as craving, hatred, ignorance, self-attachment, and self-pride in your own life, you will reach the realm of liberation. Until you liberate yourself from such afflictions (i.e., your mind is no longer governed or controlled by such mental impurities), you cannot truly enjoy the taste of liberation. However, in order to reach the state of absolute liberation, you must completely eradicate the roots of those afflictions as those roots of impurity are the causes of birth and death (samsāra). In other words, to liberate oneself from the cycle of samsāra, in the Buddhist view, is to release oneself from one’s own life of afflictions and impurities; this is the very concept of renunciation in Buddhism. Therefore, it is important to remember that—to be truly liberated—you do not have to go anywhere else but to practice the Dharma right here and right now in this person and this world.

- 6. Is Buddhism a religion or philosophy?

The modern world is home to various kinds of religions as well as various concepts of God[1]; moreover, each religion has its own doctrine and vocation. However, based on the characteristics of religions, we may generalize all world religions into two groups: a) theistic religions—religions believing in the existence of either one personal deity (monotheism) or multiple deities (polytheism) such as the Creator, God, Brahma, Gods, etc., who creates and controls the life of humans and nature; or b) non-theistic religions—religions that do not believe in the existence of any deity whose works create and control the life of both sentient and non-sentient beings. In the limit of this definition, Buddhism is a religion that does not have a personal God, but incorporates all the functions of a religion—as characterized by the modern view of religious studies—including conceptions, canonical languages, doctrines, symbols, rituals, spiritual practices, and social relationships. Yet many people today consider Buddhism to be “a philosophy of life” or “a philosophy of enlightenment”; this is just a personal choice.

- 7. What is the essential tenet of Buddhism?

The essential tenet of Buddhism was taught by the Buddha during his first teaching in the Deer Park (Sarnath), which focused on the Four Noble Truths (Catvāri āryasatyāni): the truth of suffering (dukkha), causes of suffering, cessation of suffering, and the noble path leading to the cessation of suffering. Following this first Dharma teaching, the Buddha taught about non-self—i.e., no independent entity is perpetual and invariable in the existence of five human aggregates (form, feeling, perception, mental formation, and consciousness). In other words, nothing in either the physical or mental world can be considered an immortal self or permanent ego. In addition, speaking of the Buddhist essential tenet, it is important to remember a historical fact that, on the way to enlightenment, the Buddha deeply meditated on the law of Pratītyasamutpāda (Dependent Origination), during which the Bodhisattva Siddhartha became a Buddha when he himself cut off the series of samsāra.[2] Therefore, we may conclude that the essential tenet of Buddhism includes the teachings of the Four Noble Truths, Non-self, and Dependent Origination.

- 8. If Buddhism is a non-theistic religion, can we say that it is a religion of science or one of philosophy?

You can name Buddhism as you choose, but you should keep in mind that, from the beginning, Buddhism has had no purpose to interpret or certify any problem belonging to science, as the industries of modern science do today. Buddhism does not put science at the top of its teachings; it is not inclined to any interpretation of science, although what the Buddha taught was always very scientific. The truth is that, when science is intensively developed, its discoveries help us verify the subtle problems of the Buddhist teachings, particularly those in the field of psychophysical studies. Perhaps, for this reason, Buddhism has become increasingly popular today and has quickly developed in Western countries—particularly in academic environments such as the universities of North America and Europe. However, the most fundamental doctrine of Buddhism is, as expressed in the teaching of the Four Noble Truths, to deeply realize the causes of suffering in order to transform them into true happiness and liberation. In reality, Buddhism is often called a religion of wisdom; indeed, one Buddhist expression states that “only wisdom should be a true career.” However, according to Buddhist teachings, wisdom and compassion must always go together. Thus, to be exact, wisdom and compassion are always the true career of a Bodhisattva or a Buddha.

- 9. If Buddhism already had, from the beginning, its establishment for the path of enlightenment and liberation, why did such concepts as the Great vehicle (Mahāyāna) and Small vehicle (Hīnayāna) subsequently arise in its history?

Three doctrinal movements occurred in the history of Buddhism: Theravāda, Hīnāyana, and Mahāyāna. Theravāda is the primitive form of Buddhism, which began in the time of the Buddha and continued to develop until almost one hundred years after his Nirvāna. Following this original period came the spreading of two major movements: Hīnāyana and Mahāyāna. Generally, the concept of Hīnāyana (Small vehicle) and Mahāyāna (Great vehicle) gradually emerged in the process of the expansion of Buddhist thought and philosophy. The development of these two major movements in Buddhist history gradually diverged into eighteen sub-schools. However, both major movements based their teachings on the same doctrinal foundation (i.e., the Four Noble Truths, Dependent Origination, and Non-self), although each movement had its own views and interpretations on various aspects of personal practice and social relationships. History states that, when a society develops, its languages, thoughts, and practical life also develop, thereby resulting in various views and interpretations of the Buddha’s disciples in the stretching of Buddhist history. In particular, after the Buddha had already been in Nirvāna for hundreds of years, his plain and simple teachings had, through the course of time, been covered up with philosophical reasons and social reformations. In regard to the differences in various forms of Buddhism, Buddhists nowadays often use the concept of traditional Buddhism and developed Buddhism to refer to such diversities.

- 10. How does the original form of Buddhism differ from its development?

We can summarize some basic differences between the two forms, origin and development, of Buddhism as follows:

a) Canonical languages: Primitive Buddhism (Theravāda) uses Pali as their primary language in which the Nikāya sutras (or sutta in Pali form) are the foundation for their practice. Meanwhile, Mahāyāna Buddhism uses the Mahāyāna sutras, in which Sanskrit is the primary language, together with some ancient languages, such as Tibetan and Chinese.

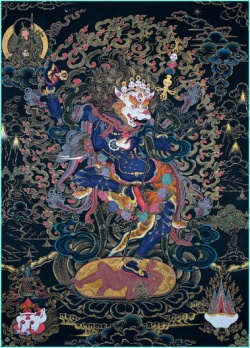

b) Thoughts: Primitive Buddhism is based on the teaching of Dependent Origination (Paticcamūpāda), while Mahāyāna Buddhism established two additional major philosophical movements: the Middle Way (Mādhyamika) and Mind-only (Yogācāra), which are also based on the same grounds of Dependent Origination. Finally, the Diamond vehicle (Vajrayāna) was the last school developed in the entire process of Buddhist development. Although these various forms of Buddhism differ somewhat, their fundamental teachings are not contradictory to one another except in regard to the conceptual expansions in the meaning of spiritual end and the problem of saving others.

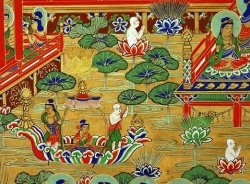

c) Practices: Primitive Buddhism concentrated on meditation in which the major themes are the four foundations of mindfulness; body, feeling, mind, and mind’s objects (all existences). Mahāyāna Buddhism expanded its forms of spiritual practice, such as Zen (meditation), Pure Land, and Tantrism; each school also has several forms of practice.

Diversity themes |

Primitive Buddhism |

Mahāyāna Buddhism |

Canonical languages |

Pali sutta/Nikāya |

Sanskrit sutras & sutras in Tibetan and Chinese |

Central thoughts |

Dependent Origination (Paticcasamūppāda) |

Middle Way (Mādhyamika) Mind-only (Yogācāra) Tantrism (Vajrayāna)

|

Practices |

Traditional meditation |

Zen, Pure Land, and Tantrism (various sects) |

- 11. In addition to the two forms of Buddhism—origin and development—why do we have the names Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism are alternative names used for primitive Buddhism and developed Buddhism. These particular names refer to the directions in which the two Buddhist traditions developed. Southern Buddhism, the primitive branch, was popularly propagated in southern India, moving toward countries such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. Meanwhile Northern Buddhism, Mahāyāna Buddhism, spanned to northern India and became popular in countries such as China, Tibet, Mongolia, Korea, Japan, and Vietnam.

- 12. Regarding practical activities, is there any difference between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

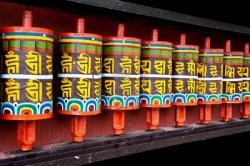

When speaking of monastic lifestyle, Southern Buddhism still maintains the primitive style for everyday activities, which were traditionally set up during the time of the Buddha. In other words, monks in Southern Buddhism all wear yellow robes, eat one meal a day at noon, study and recite the Pali sutras, etc. Accordingly, the specific feature of monks in Southern Buddhism is that they all wear the same style of robes with the same color (yellow) and all recite the same canonical language (Pali). For this reason, monks in Southern Buddhism—even from different countries—can sit down and recite the same sutra expertly and skillfully.

On the contrary, monks and nuns in Northern Buddhism do not keep the traditional lifestyle, as primitive Buddhism does. Rather, they adjusted their lifestyles in everyday activities as well as in spiritual practices, relying on different habits, customs, national cultures, and social requirements. Thus, the lifestyles of monks and nuns in Northern Buddhism are diversely dependent on various traditions of different natives. For example, monks and nuns in Northern Buddhism wear different styles of robes with different colors. Canonical languages are translated into different languages, and followers can eat more than one meal a day, depending on health issues. Generally speaking, Northern Buddhism is a form of development by nature; therefore, it has effectively adapted to social needs to become the first priority in the mission of preaching the Dharma.

- 13. Regarding the process of enlightenment, is there any difference between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

Traditionally, the process of enlightenment and emancipation of a Buddhist Holy One is concretized in the Hearer (Srāvaka)—four stages of attainment that include Stream-enterer (Sotāpana), One-returner (Sakadāgāmi), None-returner (Anāgāmi), and Complete liberation (Arhat). This process of enlightenment has been explained in detail. A holy man or woman must purify all their afflictions practically by cutting off ten fetters (samyojana) as follows:

- -Belief in an individual self (sakkāya-ditthi),

- -Doubt or uncertainty about the Dharma (vicikicchā),

- -Attachment to rites and rituals (silabata-parāmāsa),

- -Sensual desire (kāma-rāga),

- -Hatred (vyāpāda),

- -Craving for existence (rūpa-rāga),

- -Craving for non-existence (arūpa-rāga),

- -Pride in self (māna),

- -Restlessness or distraction (uddhacca), and

- -Ignorance (avijjā).

Thus, in regard to spiritual training, no difference exists between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism, although the concepts used to describe this process may vary, such as the expansion of the notion of “spiritual end” and “saving other sentient beings” in the ten stages of Mahāyāna Bodhisattva development. Briefly, although descriptions of the way to enlightenment may be diverse, the content of spiritual liberation always remains the same—namely, to attain enlightenment, an Arhat or a Boddhisattva must completely delete the ten fetters of defilement.

Process of enlightenment and liberation of a Holy one in Buddhism

Four stages of attainment |

Fetters must be deleted |

Cycle of samsāra |

Stream-enterer (Sotāpana) |

Belief in an individual self, doubt or uncertainty about the Dharma, attachment to rites and rituals |

At most, seven more births in either humans or devas (like heaven). |

One-returner (Sakadāgāmi) |

Weakened sensual desire and hatred

|

One more birth in the sense-sphere realm. |

None-returner (Anāgāmi) |

Completely deleted first five fetters: belief in an individual self, doubt or uncertainty about the Dharma, attachment to rites and rituals, sensual desire and hatred.

|

Spontaneous birth in the form realm. |

Complete liberation (Arhat) |

Completely deleted last five fetters: craving for existence, craving for non-existence, pride in self, restlessness or distraction, and ignorance.

|

None. Complete liberation from the world of samsāra. |

- 14. Can you explain more about the ten stages of Mahāyāna Bodhisattva development?

The ten stages of Mahāyāna Bodhisattva development are:

- -Pramudita: joyfulness at having overcome the afflictions and defilements and beginning to enter the Buddha’s path;

- -Vimalā: liberation from all possible defilements, the stage of purity;

- - Prabhākari: the stage of developing wisdom;

- -Arcismati: the stage of shining wisdom;

- -Sudurjayā: the stage of overcoming the utmost or subtle defilements;

- -Abhimukhi: the stage of attaining transcendent wisdom;

- -Dūramgamā: the stage of transcending all notion of self in order to save others;

- -Acalā: the stage of not falling back into impurity;

- -Sādhumati: the stage of skillful wisdom and attainment of the ten powers; and

- -Dharmamega: the stage of absolute liberation and freedom.

A holy one practices ten pāramitās (perfections) in connection to the ten stages above: dāna/charity; sīla/purity or morality; ksanti/patience; virya/progress; dhyāna/meditation; prajňā/wisdom; upaya/skillful means; pranidana/vows; bala/power; and jňāna/true knowledge.

- 15. Regarding the Buddhist ideal model for practitioners, is there any difference between Southern Buddhism and Northern Buddhism?

This is an interesting question. We know that, in all aspects of humans, the ideal model plays an important role in forming a certain personality and lifestyle for each individual, regardless of religion or non-religion. Likewise, the ideal models for practitioners between primitive Buddhism and Mahāyāna Buddhism vary.

In primitive Buddhism, the ideal model is the very image of an Arhat, a Holy one who has given up all impurities of the personal life, living in awakening and blissfulness, and teaching and helping others accordingly. However, in Mahāyāna Buddhism, the ideal model is the embodiment of a Bodhisattva, who always carries within him- or herself the vow to save others throughout the journey of spiritual training. The ideal of saving others or performing beneficial acts for all other sentient beings here is a spiritual mission with which a Bodhisattva vows to consecrate his or her life in the spiritual journey, from first vow to the day of becoming a Buddha. Consequently, in order to carry out the vow of saving others, a Bodhisattva endlessly practices and cultivates his or her wisdom and compassion. It is important to note that wisdom and compassion are the true career of a Buddha or Bodhisattva. Furthermore, to fulfill the ideal of saving others, a Bodhisattva must make a vow to enter the mundane world in thousands of worldly forms in order to benefit the world, which is why Mahāyāna Buddhism always modernizes the way of entrance to any practical life in order to benefit it. The way of practicing the Bodhisattva’s vows consists of the ten pāramitās previously addressed (see question 14), which definitely bears the same traditional characteristics of primitive Buddhism.

- 16. How many major systems of philosophy exist in Buddhism?

As we have seen, several periods of thought emerged in the process of Buddhist development. At least two major systems of thought, roughly speaking, closely related to what we call the primitive Buddhism and the developed Buddhism. The first is the Buddhist history of thoughts, as defined by Buddhologists such as academician Theodor Stcherbatsky (1866-1942); this division relied on different periods in the whole process of development of Buddhist thoughts. Second is the history of thoughts of Buddhist Schools, which includes several Buddhist schools; thus, you need to have time to study doctrines of each single school (e.g., Zen, Pure Land, or Tendai). Buddhism in China, for example, includes at least ten different schools, and each school also has its own system of thoughts and exclusive methods of practice.

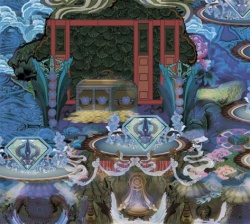

We may generally divide the first major system, the Buddhist history of thoughts, into two major categories based on history: a) Buddhist thoughts in the primitive period and b) Buddhist thoughts in the periods of development. Buddhist thoughts in the primitive period were established on the foundational teachings of Dependent Origination and non-self, which were taught directly by the Buddha after his attainment of ultimate enlightenment. The central content of these teachings explain that all existences (dharmas) in the three worlds—senses-sphere realm, fine form realm, and formless realm[3]— are nothing but the products of inter-beings from multi-conditions. They appear in either cosmic mode (e.g., institution, existence, transformation, and destruction) or in the flux of mental transformation (e.g., birth, being, alteration, and death). In this way, all things—both the physical and the mental—are born and die endlessly, dependent on multiple conditions in the cycle of samsāra. All that is present through this Law of Dependent Origination is, therefore, impermanent, ever-changing, and without any immortal entity whatsoever that is independent and perpetual__. This is the truth of reality through which the Buddha affirmed that “whether the Buddha appears or not, the reality of dharmas is always as such.” Based upon this fundamental teaching, Buddhists built for themselves an appropriate view of personal life and spiritual practice: the liberated life of non-self—the end goal of the spiritual journey.

Although Buddhist thought in periods of development were gradually formed by various schools, two prominent systems of philosophy emerged: the Mādhyamika and the Yogācāra. Both these two philosophical systems related strictly to the primitive thought of Paticcamūpāda; however, each system has its own approach to interpretations and particular concepts. The Mādhyamika developed the doctrine of Emptiness (Śūnyatā), while the Yogācāra instituted the teaching of Mind-only (Vijñapati-mātratā), emphasizing the concept of Ālaya (store consciousness). The doctrine of Emptiness focuses on explaining that the nature of all dharmas is emptiness of essence and that all dharmas are non-self by nature and existences are but manifestations of conditional elements. Thus, when a practitioner penetrates deeply into the realm of Emptiness, he or she simultaneously experiences the reality of the non-self. However, you should remember that the concept of Emptiness used here does not refer to any contradictory categories in the dualistic sphere, such as ‘yes’ and ‘no’ or ‘to be’ and ‘not to be.’ Rather, it indicates the state of true reality that goes beyond the world of dualism. For this reason, in the canonical languages of Mahāyāna Buddhism, the term Emptiness is used as a synonym for Nirvāna. In the Yogācāra philosophy, the concept of Ālaya—the most fundamental issue of this system of thought—points out that all problems of both suffering and happiness are the very outcomes of mental distinctions (vikalpa) between subject (atman) and object (dharma), or between self and other. This mental distinction is the root of all afflictions, birth-death, and samsāra. Thus, in the path of spiritual training, a practitioner must cleanse all attachments to self as it embodies what we call the ‘I’, ‘mine’, and ‘my self’ in order to return to the realm of pure mind, which is non-distinct by nature.

Based on what has been discussed here, clearly the consistency in Buddhist thoughts—whether origin or development—is that all teachings focus on purification of craving, hatred, and attachment to self in order to reach the reality of true liberation: the state of non-self or Nirvāna.

- 17. What is the fundamental belief in Buddhism?

Buddhists are encouraged to believe in the Triple Jewels—Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha—and vital teachings of the Buddha as explained in the Four Noble Truths. Put more simply, Buddhists need to believe in the basic teachings of both morality and spirituality, which extend from the Four Noble Truths such as the karmic law of causes and effects; in particular, Buddhists must believe in their own ability to attain enlightenment and spiritual liberation. If you yourself do not practice and transform all negative or even evil deeds in your own life, you shall still suffer. Conversely, if you put your efforts into practicing the Dharma, your life will be happy, peaceful, and free from the bondages of sufferings, depending on your degree of practice. Briefly, these basic teachings of Buddhism help us avoid any negative karmic actions, cultivate good actions, and purify the mind in order to have a happy and peaceful life. Furthermore, practicing the Dharma will help us transform the current of karmic force in both this life and the afterlife.

- 18. What is the karmic law of causes and effects?

To be exact, karma and the law of causes and effects are the two most important issues strictly connected to the life of human beings. They are also considered to be the reason for the existence of human beings in the cycle of samsāra. Literally, cause is the original force or reason that produces a direct effect and effect is a mature consequence created by its causes. You can understand the relationship of causes and effects through the correlations of an action, such as when you eat, your stomach is full, or when stay up late, you feel sleepy. Causes and effects are the compensational law, working objectively and correspondingly, but the actual impact is always influenced by psychological elements. Contrastingly, karma refers to a good or bad action that is created and governed by the mind. A proper name for such actions is wholesome karma or unwholesome karma. Accordingly, karma and causes and effects always connect to each other; in other words, karma is the operation of causes and effects in which the mind always serves as the foundation for any creation and destruction. Therefore, the current of mental energy is the life of karma. Truly, a good mind produces good karma and a bad mind gives birth to bad karma. Hence, in order to have a life of peace and happiness, you should cultivate the wholesome seeds through your three personal karmas and develop the pure and bright energy of the mind. Buddhism teaches that a practitioner must always nurture and cultivate the four virtues of the sublime mind: loving kindness, compassion, joyfulness, and equanimity.

- 19. What are the three karmas?

The three karmas are the body, mouth, and mind or the physical, verbal, and mental. Body and mouth belong to the physical realm while the mind is all about psychological activities. However, it is the mind that serves as the decisive factor in creating any kind of karma (Cittamātram lokam—the world is nothing but mind.) A natural action like standing, walking, lying, or sitting cannot create karma actually, except that the action is governed by the mind. Thus, actual karma always comes from a volitional action or an intentional action. For this reason, the Buddha divided the three karmas according to the three aspects of the physical, verbal, and mental into ten karmas:

- a) Physical karmas: Killing, stealing, and conducting sexual immorality.

- b) Verbal karmas: False speech, a double tongue, hateful speech, and slanderous speech.

- c) Mental karmas: Craving, hatred, and ignorance or false view.

These ten basic karmas are the causes that force us adrift in the ocean of samsāra, with its six realms of destinations.

- 20. What does Samsāra mean in Buddhism and how does it work?

In Sanskrit, samsāra means being born, dying, and being reborn in accordance with the continuous karmic circulation, like a wheel circulating endlessly. Thus, samsāra is the cycle of life. However, the concept of samsāra in Buddhism describes the flowing of a sentient being in the three worlds (senses-sphere realm, fine form realm, and formless realm) and six destinations (heavens, human beings, titans, hells, hungry ghosts, and animal kingdom). According to primitive Buddhism, only an enlightened one (such as the Buddha or an Arhat) can truly be liberated from the cycle of samsāra. Meanwhile, in Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Bodhisattvas always vow to return to the world of samsāra to save all sentient beings. Therefore, there are two ways to enter the world of samsāra: a) vow to be reborn, as a Bodhisattva does voluntarily, and b) be forced to enter a certain realm, like a human, hell, or hungry ghost, by the unwholesome karmas of each individual.

- 21. If Buddhism does not believe in an immortal soul, then what and who will be reborn in the cycle of samsāra?

This is an interesting question. Buddhism definitely does not accept the belief that there is an immortal and perpetual soul. As mentioned in the teaching of non-self, no permanent self or soul entity exists permanently and invariably—only the current of karmic consciousness of sentient beings flowing constantly like the running of a river. If there were an immortal and invariable soul, an animal would not be able—after cultivating wholesome karmas through multiple lives—to become a human and a human would not be able to become a Bodhisattva or even a Buddha (See Jataka Tales for more information). Here, it is the very karmic current of consciousness that continually operates and transforms itself from this life to the next life in the cycle of samsāra in which the mind of each individual is the only foundation for this operation (see question 18). Consequently, Buddhism does not accept the existence of an immortal soul, although it does accept that a transformation of the mind occurs throughout the journey of birth and rebirth. Until a practitioner—after a long term of spiritual training—attains sainted fruits such as Arhat, Buddha, or Bodhisattva in the eighth stage, he or she will break the cycle of samsāra. At this point of the spiritual journey, the motivation of birth and rebirth belongs to the devotional vow of each Bodhisattva; it is no longer pushed by the karmic force. Speaking of problems of rebirth or samsāra, you should note that Buddhism does not use the term soul, but rather mind.

- 22. How can one know that he or she will be reborn in the cycle of samsāra?

This question goes beyond the ability of human knowledge because we human beings are not able to control the problem of birth and death in the cycle of samsāra subjectively. According to the Buddhist view, we are all adrift in the ocean of karma unknowingly and inconceivably. If you were asked “where did you come from?” you would also be puzzled in the same way; however, to the Buddha, Arhats, or Holy ones who all already possess supernatural eyes (spiritual powers), such a question as “where did one come and where will one go?” is no longer an uncertain matter left in the dark. The Buddha in Jātaka Tales told us many of his own stories of previous lives when he used to be a practitioner practicing the noble path. However, as the karmic law of causes and effects has already explained, you need not worry about where you will go after death; rather, what you need to know is how you are living and how your mind develops. Are you cultivating good or bad karmas? The karmic law of causes and effects will itself manage all the remaining matters of your life. However, if you are a practitioner, you may make a devotional vow for your next rebirth depending on your school of practice. For example, a practitioner in Pure Land always wishes to be reborn in the Western Paradise of the Amitāba Buddha after his or her life ends.

- 23. Buddhist mental formations include such concepts as the mind, thought, and consciousness. How different are they?

In primitive Buddhism, the three terms mind, thought, and consciousness are used interchangeably according to various statuses, despite the fact that these three terms all indicate the entire activities of the mental formations. In developed Buddhism, particularly in the doctrine of Mind-only (Vijñapati-mātratā) of Yogācāra philosophy, the system of mental activities consists of eight consciousnesses categorized as follows:

- a) Thought consciousness (pravrtti-vijňāna): This senses-sphere includes six sense organs: consciousness of the eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and thought.

- b) Thinking consciousness (mano-mana-vijňāna): This consciousness’s function serves as the intermediary connection between the six senses organs and the mind deep inside; it is also referred to as the seventh consciousness.

- c) Store consciousness (ālaya): This serves as the store that contains all kinds of conceptual seeds (experiential data) of the past and present; it is also named the eighth consciousness.

Together these three consciousnesses are generally called the mind; they all work together in order to produce an actual experience through a process of psychological processing. For instance, when your eyes see a flower, the notion of that flower will be transferred into the store consciousness—where images of all kinds of flowers of your past experiences have been stored—through the thinking consciousness in order to process and produce the actual recognition that it is a rose. Subsequently, this rose’s characteristics and smells, etc., all must go through a process of mutual recognition until you are finally able to create an actual experience of the rose that you have just seen.

Briefly, mind, thought, and consciousness are the mental aggregate of human psychological activity. This mental aggregate exists as a whole; it cannot work effectively if we divide it into separate parts. However, you can clarify the basic function of each characteristic of this mental aggregate. The mind is the place where all conceptual data are stored, thought is the mental energy of creation, and consciousness is the ability of recognition and distinction. Suffering or happiness is created by the operation of the mind, thought, and consciousness; all other realms of sentient beings are also products of the mind’s making.

- 24. If there is no existence of God, then on what condition is the existence of heaven and hell based?

Everything is mind-made, but you should never use the impure mind of the human realm to think about the blissfulness and happiness of other realms, such as heavens (states of devas) or the Pure Land. Doing so would be an impossible task. In much the same way, you cannot truly understand the suffering of lower realms (compared to the human realm), such as hell, the hungry ghosts’, and animal kingdoms. However, to a certain extent or in particular cases, you may somewhat experience the suffering and happiness of other realms when your mind is corresponding to those realms. For instance, when nearing the peak of anger, you may feel and experience the suffering of realms that are full of anger. When your mind is no longer infected or disturbed by craving, hatred, and ill-will, you will experience the taste of blissfulness and freedom in the happy realms. According to Buddhist teachings, celestial beings (devas) in the realm of fine-form (heavens) live in the blissfulness of their own minds, and all conveniences in those heavens are created by their own minds. However, when their own merits of heaven have faded, those celestial beings will be reborn in (fall into) lower realms. If they put their efforts into practicing the Dharma, they will certainly be free from the cycle of samsāra and attain enlightenment. Similarly, sentient beings in unhappy realms experience the suffering also made up by their minds; however, beings in unhappy realms can still remain free of those states if they have a chance to generate the righteous mind of goodness.

- 25. If all comes from the mind, can a non-Buddhist practice the Buddhist doctrine?

Everyone—Buddhist or non-Buddhist—can practice the noble Dharma taught by the Buddha equally. Certainly, those who follow the way of practicing Dharma precisely and sincerely will be able to change and transform their karmic life of defilements, at least in the present being. For those who are non-Buddhists, their practice in the Buddhist way needs to be guided by a monk, nun, or any layperson who has some experience in terms of spiritual training. As such, you are encouraged to study and examine the Buddhist teachings under the guidance of a master. The practice of Dharma will bring to us actual effects whenever our mental current of greed, hatred, self-attachment, and self-pride begin to change in the tendency of cooling down. If you just study the Dharma or even have a great knowledge of Dharma, but those mental afflictions do not decrease or weaken, you have not practiced the Dharma and never exercised any mental improvement practically.

- 26. What is the primary core of spiritual practice in Buddhism?

The primary core of spiritual practice in Buddhism—regardless of any school, whether traditional or modern—is to develop ethics (sīla), meditation (samādhi), and wisdom (prajňā). First, to practice ethics or moral disciplines is to prevent and avoid unwholesome deeds as well as cultivate human dignity, especially to restrain the ability of performing evil deeds potentially hidden in the mind. In other words, developing Sīla is training oneself for a life of ethics, dignity, and noble virtues. Second, practicing meditation is the way by which one can purify all affections and afflictions in the mind and make it pure, peaceful, and bright. Finally, practicing wisdom means developing the right view, recognizing truths, understanding the nature of life, and attaining enlightenment. These three aspects of this path of practice always supplement one another. For example, the one who lives a life of high ethical discipline and noble virtues will have a peaceful mind, self-confidence, and fearlessness. The one who develops meditation will have a quiet, calm, and blissful mind. The one who develops wisdom will have a bright, smart, and tranquil mind, always and everywhere. You may gain various results of your mental training, according to the various degrees of practice. Buddhism calls these three aspects of practice the pure studies (anāsrava) of deliverance from the passion stream; in other words, you no longer fall into the stream of samsāra, truly liberating yourself from all impurities of the mundane world.

- 27. Is there any difference in the manner of practice of Buddhism and that of other religions?

In regards to the manner of spiritual practice, other religions focus on prayers as a way of connecting to the Holy existence; Buddhist practice focuses on developing (bhāvanā) the three studies (ethical disciplines, meditation, and wisdom), although prayers are still sometimes applied in the process of practice. The term bhāvanā (development) in Buddhism has a special meaning that includes two parts: a) renunciation of unwholesome deeds and b) development of noble virtues such as loving kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy, equanimity, and performances of pāramitās (see question 14). If you focus on the first part—namely, the renunciation of unwholesome deeds—you are only stopping at the point of not doing evil; at such a point, you have actually not undertaken any spiritual training. For example, an addict who drinks alcohol for many years becomes seriously sick; being aware of his illness, he stops drinking. Such an action means he is just giving up his habit of alcoholic addiction. The remaining matter he has to deal with is healing the illness in his body, simultaneously developing his health as well as his wholesome life both physically and mentally. Similarly, in Buddhist practice, you have to do both: quit all evil deeds you have done and cultivate the good deeds you have not yet done. In brief, the fundamental Buddhist practice is not to do evil, to do good deeds, and to purify one’s mind through the noble path of ethical disciplines, meditation, and wisdom.

- 28. Does one benefit if he practices just one of the three pure studies

- moral discipline, meditation, or wisdom?

You should keep in mind that the three pure studies—ethical discipline, meditation, and wisdom—are three facets (more precisely, three elementary characteristics) of spiritual practice in Buddhism. They are considered a group quality working mutually and cooperatively. For instance, when practicing ethical disciplines, your mind will be pure, peaceful, fearless, and free from worriment and sorrow, which is all about the quality of meditation or concentration. These pure qualities of course will lead you to a higher level of meditation. Furthermore, based on this pure mind, you will be able to set yourself up for the right view and bright choice, guiding you in everyday activities. In this way, it is all about the quality of wisdom. Ethical discipline, meditation, and wisdom are, therefore, a group quality, always working together. For example, how can a bank robber be peaceful and tranquil while having true wisdom in life and truths when his mind full of greed, hatred, and ill will? Accordingly, the greater ethical virtue is, the higher meditation develops and the brighter wisdom will be. Thus, you need not divide this group of qualities into separate parts in the path of spiritual practice.

- 29. How can a person become a Buddhist?

Becoming an actual Buddhist, you must take refuge in the Triple Jewels—Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. Buddha is the Fully Enlightened One, who transcended beyond the world of defilements (kleśa) and samsāra. Dharma is the teachings of the Buddha, the noble path to enlightenment. Sangha is the Buddhist community that lives in harmony and awareness, such as monks and nuns, following the path of the Buddha. However, the Triple Jewels can be understood in various ways, as described in the following table.

Classification |

Buddha |

Dharma |

Sangha |

History |

The Sakyamuni Buddha |

The teachings of the Buddha collected in the Triple Basket (Tripitaka). |

Community of monastic persons, including Holy Ones and monks and nuns. |

Definition |

An Enlightened One |

The noble path leading to enlightenment and ultimate liberation. |

Those spiritual practitioners who live in awareness, harmony, and purity. |

Symbols |

Images of the Buddha or Buddhas |

The Triple Basket (Tripitaka) or Buddhist scriptures, texts of ethical disciplines (Vinaya), and commentaries (Abhidharmas). |

Buddhist monks and nuns. |

Philosophy |

The Buddhahood or Buddha nature is always available in every person. |

The truth of enlightenment. |

The essence of harmony, awareness, and purity in every person. |

The basic ethical discipline of a Buddhist is also the foundation of Buddhist ethics, including five precepts: not to kill, not to steal, not to be involve in sexual immorality, not to lie, and not to use intoxicants. Being a Buddhist, you must undertake at least one of the five precepts. The more fully you practice the precept, the higher your ethical virtues develop, and the greater dignity you will seek to achieve.

- 30. Why must a person take refuge in the Triple Jewels to become a Buddhist?

If you do not have a sincere desire to take refuge in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha (Triple Jewels), it means that your decision and devotion are not strong enough for you to sow the Bodhi seed (seed of enlightenment) in your own mind. In fact, you may ethically perform various wholesome deeds in a very natural way directed by your own congenital temperament. However, if an outburst of rage and ill will suddenly emerges in your mind, it may whirl you, sweeping you impotently into the darkness of your own karmic habits. In such a situation, you may be engulfed in sin after sin, for at this point in life, you still have no coast of enlightenment as your own spiritual refuge or shelter. Once you have taken refuge in the Triple Jewels, you have sown a seed of Bodhi in your field of mind. If you always take good care of your own Bodhi tree by practicing the Dharma, you are creating for yourself an invisible current of protective energy and bearing that current of energy with you throughout life. Thus, even when the mental storm of greed, hatred, and ill will emerges in your life and disturbs your inner peace, this invisible energy of protection provides the very spiritual shelter for you. It will, at a certain point in your life, regenerate the Bodhi seed that latently slept in the bottom of your mind—the very enlightened energy you once sowed with all sincerity and devotion. Even if—after taking refuge in the Triple Jewels—you neglectfully care for or completely ignore your Bodhi seed, that enlightened seed still sleeps in your mind soundly; it may be awakened at any time in the right conditions, like an old friend coming back with earnestness and love. Now, in the light and love of that spiritual regeneration, you are able to continue to nurture the enlightened source of your own Bodhi tree that was once forgotten. This is why a Buddhist needs to take refuge in the Triple Jewels.

- 31. Can a person attain enlightenment and liberation if he just practices the Dharma without taking refuge?

Yes, but it is really rare! The Buddha Sakyamuni is the one person in history who attained enlightenment based on his self-training, self-discovery, and self-realization; his personal efforts cut off all roots of suffering. He is honored for his attainment of full enlightenment by self-realization of truths. Furthermore, the Buddha’s first five Holy disciples as well as other Holy ones in the Buddha’s time became enlightened or Arhats not by taking refuge, but by listening to the Dharma directly taught by the Buddha. Likewise, Prateyka-Buddha(s) achieve enlightenment through their own realization of the truth of Dependent Origination. Generally, achieving enlightenment without taking refuge in the Triple Jewels is really rare in the realm of human beings, particularly for an ordinary person. You should keep in mind that taking refuge in the Triple Jewels is the first step in becoming an actual Buddhist. However, to be enlightened and liberated or not depends on the ability of your spiritual training. In fact, after taking refuge, a Buddhist must practice the Dharma in a step-by-step manner, such as ethical disciplines, six Pāramitās, or four all-embracing virtues (Catuh-samgraha-vastu), in order to have a peaceful and happy life.

- 32. Is the moral discipline of Buddhism similar to or different from that of other religions?

Buddhist ethics and other religions have some common features and some differences. The common features belong to the human base of morality and ethics relating directly to the life of humanity. Meanwhile, the differences between the Buddhist moral disciplines and that of other religions relate to the path of enlightenment and spiritual liberation. Thus, we should be concerned about two aspects:

a) Human base of morality and ethics: Buddhist ethics are based on the five precepts (not killing or doing harm to the life of humans and sentient beings, not stealing or taking things that are not given, not conducting sexual immorality, not lying in order to do harm to one’s self or others, and not using intoxicants that weaken the mind). Christianity teaches ten commandments (worship God, do not make yourself an idol, not making false use of the name of God, keep the Sabbath holy, honor and respect your parents, not committing murder, not committing adultery, not stealing, not bearing false witness against your neighbor, not coveting your neighbor’s wife, and not coveting things that belong to others). Likewise, Islam teaches some fundamental creeds, such as worshiping the one and only Allah, honoring and respecting your parents, respecting the rights of others, treating all people fairly, giving to and helping the poor, not killing humans except in holy wars, not committing adultery, taking care of orphans and the poor, and being sincere in all of your intentions. In addition, Islam includes some conductive regulations, such as visiting Mecca at least once in your life, not eating pork, and not drinking alcohol. The issues mentioned here cover the common interests of all religions relating to the human ground of morality and ethics.

b) Buddhist ethics—the path leading to enlightenment and spiritual liberation: The five precepts (ethical disciplines) in Buddhism fully associated with the three personal karmas—the physical, verbal, and mental—are physical karmas (killing, stealing, and conducting sexual immorality), verbal karmas (false speech, a double tongue, hateful speech, and slanderous speech), and mental karmas (craving, hatred, and ignorance or false view). Therefore, if you are able to keep your three karmas completely pure, you yourself will enter the palace of Nirvāna, truly experiencing the life of true liberation and enlightenment. However, the mental karma—the third one—is here the most fundamental element that governs and drives the other two karmas, the physical and verbal (see question 19). Thus, building an actual right view for your own life is the key that opens the door to spiritual liberation. In Buddhist ethical disciplines, as previously discussed, no precept requires a practitioner to honor or worship a personal God; rather, all that is focused on is the spiritual training of personal purification of the three karmas. This is the very difference between the Buddhist precepts and the creeds of other religions. In addition to these five basic precepts, Buddhism also has a special system of moral code that is more rigorous for monastic persons (the moral disciplines for Holy ones such as Srāvakas and Bodhisattvas). However, for lay Buddhists, in addition to taking the five basic precepts, you need to practice four acts called all-embracing virtues and the six deeds of Pāramitās in order to develop wholesome roots (wholesome karmas) and nurture your Bodhi mind for your own spiritual life.

- 33. What are the four all-embracing virtues (Catuh-samgraha-vastu)?

The four all-embracing virtues are four actions concentrating on helping others achieve a true life of peace, happiness, and spiritual liberation. Thus, these four actions are named four all-embracing virtues (Catuh-samgraha-vastu) for these actions have the ability to transform others and help them return to the truth of life free from defilements and sufferings. The four all-embracing virtues consist of donation, affectionate speech, the conduction of profit to others, and cooperation with and adaptation of others. The following table describes the general meaning of these four virtues.

Samgraha-vastu |

Definition |

Categories |

Purposes |

Donation |

Charitable acts of giving, dedicating, or offering to others. |

(a) Materials, (b) True knowledge (Dharma donation), and (c) Security (fearlessness, bestowing of confidence) |

Sharing sufferings of others and helping them return to the good and happy life. |

Affectionate speech |

Speech filled with kindness, sympathy, and compassion. |

True and honest speech at the right time, in the right way, and filled with encouragement. |

Encouraging others to live wholesomely and ethically, avoiding doing evil, doing good, and purifying the mind. |

Conduct beneficial to others |

Doing beneficial acts for others or serving others with kindness and compassion. |

Conducting good deeds through personal body, speech, and thought. |

Helping others benefit along the path of spiritual practice. |

Cooperation with and adaptation of others |

Cooperating with others practically in order to help them return to the noble path of enlightenment. |

Applying all skillful means of personal ability to help others. |

Helping others return to the noble path of spiritual liberation and enlightenment. |

- 34. What are the deeds of pāramita (transcendental perfection)?

Pāramita is the characteristic of transcendental perfection that goes beyond the world of dualism, such as attachment to the self and others or the inner discrimination between atman and dharma. This transcendental perfection is also known as the spirit of non-distinction and non-attachment. For instance, you give a donation to someone; however, at the back of your mind, you are still entangled in the thought of that donation, identifying the giver and the receiver. Donations to others in such a manner result in attachment to the performance of giving—namely, giving in the bondage of the self and others. It is absolutely not giving from your true heart of compassion without any strings attached. Until you give a gift to someone without any attachment to the notion of the giver, the receiver, or the gift, you cannot truly reach the state of non-attachment to the act of giving—that is, the true giving free from the three-wheeled condition of giver, receiver, and gift. Therefore, practicing the deeds of Pāramita is but training renunciations of self-attachment and distinction. The Pāramita deeds include six factors: giving, practicing ethical disciplines, right efforts, patience, meditation, and wisdom.

- 35. What is the Bodhi mind (Bodhicitta)?

The Bodhi-mind (Bodhicitta) in Sanskrit is the mind (citta) of awakening (bodhi), also named the enlightened mind, the mind orientating toward enlightenment, or the mind that tranquilly resides in the state of awakening. However, the Bodhi-mind, in Buddhist thought, is understood through two basic aspects: the conventional—namely, the daily practice of ethics, virtues, and merits in order to achieve the noble happiness and peace in practical life—and the absolute—namely, the full awakening of the Perfect Wisdom, becoming a Holy one, a Bodhisattva, or a Buddha. Thus, the Bodhi mind is the heart of Buddhism, the foundation for the whole process of spiritual training of Buddhist practitioners. Accordingly, if a person does not nurture and take good care of the Bodhi mind, his own Buddhahood will be buried by karmic defilements. You should absolutely keep in mind that the Bodhi mind is the Buddha nature within each person, which is the very seed (potentiality) of true happiness and enlightenment. Traditional Buddhism includes several practices to help you develop the Bodhi mind, including 37 conditions leading to Bodhi (Bodhipaksika): four foundations of mindfulness, four right efforts, four steps towards supernatural powers, five spiritual faculties and their five powers, seven branches of enlightenment, and the eightfold noble path.

- 36. What are the four foundations of mindfulness?

The four foundations of mindfulness (smrti-upasthàna) are the ground of practicing meditation. These four foundations are also known as the four themes of mindfulness (smrti) in the process of meditating. They are body, feeling, mind, and the mind and mind’s objects. The following table categorizes the position and functions of these four foundations of mindfulness.

Four themes |

Categories |

Meanings |

Purpose |

Body |

The entire physical body including the inside and the outside. |

Meditate on the body in order to realize its true nature of impermanence and impurity. |

Leaving afar or renunciation of the cravings of the senses-sphere realm, fine form realm, and formless realm. |

Feelings |

Feelings of pleasantness, pain, and neutral. |

Meditate on the feelings in order to clearly see that they are actually conditions (foods) of the mind. |

Cutting off the roots of all kinds of cravings. |

The mind |

The current of mental energy, which is endlessly flowing. |

Meditate on the mind in order to recognize its operation and manifestations through various kinds of thoughts, such as greed, hatred, ill will, self-pride, self-attachment, and doubt. |

Removing all kinds of attachment and false views of self in order to reach pure states and develop wisdom. |

The mind and mind’s objects |

All kinds of forms (mental and physical), sounds, smells, tastes, touch, and objects of the mind (all things recognized by the mind). |

Meditate on forms or existing beings in order to see their status of changing, such as institution, existence, deterioration, and destruction. |

Attaining pure wisdom, blissfulness, and ultimate liberation. |

- 37. What are the four right efforts (catvāri prahāṇāni)?

The right efforts are devotional endeavors towards a virtuous life in order to cut off the defiled roots and cultivate wholesome roots in the field of the mind. There are four right efforts with which a practitioner must train himself along the path of spiritual development: a) the effort to discard all evil deeds that are already done so as not to commit them again; b) the effort to prevent evil deeds that have yet to arise; c) the effort to maintain and promote the further growth of good deeds that have already arisen; and d) the effort to generate and develop unborn good deeds.

- 38. What are the four supernatural powers (rddhipāda)?

The four supernatural powers are four special powers of the pure mind leading to concentration (samādhi) and/or working in concentration independent of any ordinary or natural law. They are also known as the four exclusive characteristics of meditation (dhyāna). These four powers are: a) the desire for intense concentration (chanda-rddhi-pāda)—strong devotion to self-purification that creates extensive concentration during the time of meditation; b) persevering energy or intensified effort (Vīrya-rddhi-pāda) that creates the power of concentration (samādhibala) in meditation; c) the powerful mind in the stage of freedom from all defilements (citta-rddhi-pāda) in meditation; and d) the power of intense observation (mimāmsā-rddhi-pāda) in meditation. When a practitioner attains these four special powers in meditation, he or she perfectly achieves the four supernatural powers of meditation.

- 39. What are the five spiritual faculties (pañcānām indriyāṇām) and their five powers (pañcānāṃ balānām)?

The five spiritual faculties are five fundamental agents upon which you may develop your state of spirituality, including belief, persevering effort, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. The five powers are the five mental forces that arise from the above five spiritual faculties: powers of belief, persevering effort, mindfulness, concentration, and wisdom. In the process of spiritual training, you should develop all five faculties because they are mutually incorporated with one another. For instance, if you have a strong belief in what you are doing, you are then able to put all your efforts into doing it so that you may reach the end goal. In addition, when your effort is directed in the principle of mindfulness, you may generate for yourself an inner source of powerful concentration and wisdom. All Buddhist schools of practice must always consist of these five faculties and their five corresponding powers. The five spiritual faculties differ from the five physical organs (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, and body.)

- 40. What are the seven branches of enlightenment (saptabodhyanga)?

The seven branches of enlightenment are seven elements in the state of awakening or seven factors of a peaceful and liberated life of enlightenment. They consist of mindfulness (smrti), investigation of dharma (dharma-pravicaya-sambhodyanga), persevering effort (vīriya), rapture (prīti), calmness (prasrabidhi), concentration (samādhi), and equanimity (upeksā). If you develop these seven characteristics to the perfect degree, you will attain the blissfulness of enlightenment and liberation.

- 41. What is the noble eightfold path?

The noble eightfold path is the Holy path to enlightenment; it includes eight branches: a) right view (samyak-dṛṣṭi), the view that is always in accordance with the truth; b) right thought (samyak-saṃkalpa), the thinking or intention that is in accordance with the truth, leading to the virtuous life of true peace and happiness; c) right speech (samyak-vāc), the speech of truth that is in accordance with Dharma; d) right action (samyak-karmānta), doing good deeds; e) right livelihood (samyak-ājīva), the noble life of goodness, virtue, and ethics; f) right effort (samyak-vyāyāma), diligence in practicing ethical disciplines, meditation, and wisdom; g) right mindfulness (samyak-smṛti), an action performed with attention, awareness, and alertness; and h) right concentration (samyak-samādhi), the concentration or meditation that leads to the renunciation of craving, hatred, ill will, self-attachment, etc. The noble eightfold path is the guideline for spiritual practice in the Buddhist life. Each branch of the eightfold path works with the others mutually. Thus, you can divide the eightfold path into the pattern of the three pure studies, as follows:

- Prajñā (wisdom) - Right view and right thought

- Śīla (ethical discipline) - Right speech, right action, and right livelihood

- Samādhi (meditation) - Right effort, right mindfulness, and right concentration

The term right (samyak) always stands in front of each branch to remind us of the difference between right and wrong. For instance, the right view (non-attachment to the self) differs from the wrong view (attachment to the self and other); the right livelihood (good life) differs from the wrong livelihood (evil life).

- 42. Is there any plain and simple teaching that can be remembered most easily?

The Dharma that can be remembered most easily was taught by the Buddha:

- Not to do evil,

- To do good,

- To purify one’s mind,

- This is the teaching of the Buddhas

- (Dhammapada.183).

- 43. Why do we eat vegetarian foods?

Maintaining a vegetarian diet has become increasingly popular for several reasons, such as improving health, controlling sexual desire, or protecting animals and environments. Eating vegetarian foods means not eating the meat of any animal. The aim of eating vegetarian foods in Buddhism is to purify your three karmas, particularly the karma of killing sentient beings either directly or indirectly. Refraining from meat is also one way to develop your compassion. As a lay Buddhist, you are not prohibited from eating meat, but you are encouraged not to do so either periodically or permanently.

- 44. Can a person become a Buddha by eating purely vegetarian foods, and how is vegetarianism related to spiritual practice?

No one in history has ever become a Buddha simply by eating vegetarian foods. You should keep in mind that eating vegetarian foods is one way to support your practice of personal purification, both physically and mentally. However, achieving the life of awakening is always comprised of the three pure studies: ethical disciplines, meditation, and wisdom.

- 45. Does a Buddhist break the precept of not killing when he eats meat?

By eating meat, you may break the first precept (not killing) in three specific cases: a) you yourself kill an animal to make food; b) you order other people to kill an animal to make food for you; and/or c) you are satisfied by seeing other people kill an animal to make food for you. In these three cases, the first one directly commits killing while the last two are considered indirectly breaking the precept.

- 46. What does repentance (Ksamayati) mean in Buddhist rites?

“Repentance” in Sanskrit is Ksamayati, translated into English as repentance and remorse. Basically, Ksamayati includes two crucial parts: a) repentance—to feel regret or contrition for a past sin or guiltiness—and b) remorse—to be gnawed at, be distressed by, or suffer from a sense of guilt for past wrongs for which you promise yourself not to commit again. Briefly, when you perform repentances, you know that you sinned or were guilty; being aware of that sin, you honestly repent in your own remorse and promise that you will never commit that sin again. However, when performing a repentance ritual, your body and mind must unite together in a respectful manner (e.g., adornments by both physical and mental purification); in the state of one-pointed mind, you earnestly and sincerely pray and make a promise in front of the Triple Jewels. With your true esteemed respect, after repentance, your own body, mouth, and mind will become pure. The level of purification depends on your sincerity; the more profound your sincerity is, the more ease you will feel, regardless of whether you repent in front of the Triple Jewels or face your own conscience. The Buddha taught that two classes of noble persons can be found in the world: the first one is the person who lives nobly and never creates a sin—even a simple one; the second one is the person who has the awareness of sin and is always ready to repent whenever he commits one.

- 47. Can a person’s unwholesome karmas be eradicated through repentance?

What you have sown (created or done) in the past shall definitely come to fruition when its time of maturation arrives. When you honestly repent for your sins properly, you may transform your own karmic force through two aspects: not creating more sin and cultivating good deeds. However, with the mind of purity, tranquility, control, and renunciation (the liberated mind), the mature effect from past deeds—whether painful or pleasant—is not powerful enough and no longer governs the life of your inner peace and tranquility. When your mind is absolutely pure as snow, no sin remains; even the notion of remorse is removed. At this point of purification, you actually go beyond the dualistic realm of birth and death. In such a state, the problem of causes and effects is no longer discussed.

- 48. What is the aim of reciting the Buddhas’ names?