Towards an Australian future without Buddhism by Ven. Mujyo

Towards an Australian future without Buddhism

Ven. Mujyo , Jizoan Zen Temple, Perth

When the Historical Buddha Sakyamuni first wondered about suffering, its nature, the nature of cessation and whether it could be overcome, perhaps he wasn’t the first. In fact the word Buddha, Enlightened one precedes Buddhism, and many Yogis like himself set out to overcome suffering – Dakka. What was significant is the depth of Sakyamuni’s realization and his teaching of the middle way and the subsequent development of Buddhism as a spiritual system. However a significant problem especially in the time of consumerism is the packaging of that middle way as a product. This paper seeks to explore the contradiction between the Dharma and the ‘ism’ of Buddhism as it becomes established in Australia.

The idea of Buddhism is the biggest impediment to Buddhism

The Zen master Mumon puts it like this;

‘You kill the Buddha if you meet him, you kill the Ancestor if you meet them… with great joy, a genuine life in complete freedom’

A Chinese Poem says;

‘If you meet a Poet show him your Poem, if you meet a man who is not a swordsman do not show him your sword’

Killing is breaking the first precept, but killing here is freedom, but since Buddha from a Mahayana point of view is none other than you who then wields the sword and who then is killed? If I don’t kill the Buddha then how is the first precept protected? If the Buddha and Dharma is Other, that can be killed, how can I pass?

Another Zen teacher, Joshu, exclaimed, ‘Buddha – that is a word I don’t like to hear!’

These sentiments are used in Zen as koans, as koans they challenge us to look within. Where is Buddha? Who is Buddha? What is Buddhism? If we begin Buddhism in Australia like this we may have a chance. Is the Buddha separate from us? Are we separate from the temple; is the effigy representing Buddha nature, or authoritive separation? If we teach people to love the names and images then we have bound them up in rope and Buddhism in Australia cannot be anything but an ‘ism’. Ism in the negative sense of representing an affected philosophy.

So the biggest impediment to Buddhism in Australia if we are not very careful is Buddhism it’s self. That means that Buddhism the vehicle of freedom becomes a prison.

Buddhism is as a vehicle the arbitrary device that Buddhas and Bodhisattvas use, only that. Like this physical body to be used and renewed but not be thought of as the Dharma, it’s self.

“Be a lamp”, the Buddha said, lamps are just tools to see with. Dharmakaya is a different kind of body and not meant to create attachment. In fact there can be no attachment by definition to true freedom, or it is not Dharmakaya.

The impact of this relates to how we see the institution of Buddhism. A person who loves something very much often thinks everyone else loves it too, or at least should. In such a case love becomes wanting, wanting becomes jealousy, jealousy becomes killing. Not the killing that Rinzai speaks of in the above case, which is freedom, but killing in the negative sense. Thereby as I said Buddhism it’s self which should be the vehicle to bring people closer to the great matter becomes something that divides them from it. In loving the Dharma I set my self apart from it.

Does this mean we shouldn’t have temples, clergy and clothes and other ritual items. No that would be to divert blame and in the end if people cling to devices they will replace one device with another. The contemporary styled dharma teacher just by clothes speech and the environment he/she teaches in is not necessarily any different from the Monk or Nun. Any suggestion so is performance for audience, smoke and mirrors tricks. Instead it means we should always see them as expedient tools and no more.

Faith is one of the Three Pillars of practice, but it should not become another form of conditioning, the others being Doubt and Awakening, none of the three exclusive of each other.

Buddhism as a means unto it’s self is not the teaching of Sakyamuni

Buddhism that exists only as a means to support an orthodoxy is unhealthy and parasitic. Buddhism as it introduces into Australia has the opportunity to address this, however imperfectly.

Buddhism should be vibrant and accessible to Australians. Temples and groups should exist as a means to contribute to Australian society not the other way around. Already in Australia over the last 45 years Australia has undergone a huge secularization. No longer do Australians feel obligated to follow a particular religion, in fact Australians by and large while open to spirituality do not hope for religious orthodoxy. Australia has moved towards a secular character.

Buddhism should not expect special favours in Australia. Buddhism should not seek to become just another institution without making serious contributions to Australian society and respecting the freedoms of that society. By and large Australia and the Buddha way is a good fit, if taught and practiced with sincerity.

If the temple is a monk’s living and just that, then the activity of the temple becomes false. The dharma becomes a commodity to trade and the community of supporters and sangha customers or peddlers as per case. Buddhism is not owed a living in Australia simply because its traditions assert to be the correct transmitters of the Dharma.

Buddhism should contribute creatively to Australian life and ideals. Such as in the environment by informing bio-ethics, arts creativity, science ethics. In this way Buddhism while fitting the secular nature of Australian society creates within the society. The nature of the Buddhist teachings and practice are positive, and long dead are feudal times when a religion could simply rest on portents of impending doom from sin and corruption. Instead any religion in Australia should move on and find contributing paradigms.

The difficulty created by Multiculturalism

Multiculturalism, as government policy in Australia, by its self may be a noble idea promoting equality between groups in principle, however as implemented in Australia it serves in Buddhism to turn temples and practice groups in cultural clubs vying for grants and influence over policy. In this regard passive interference from government is rewarding bad Buddhism at the expense of good.

Instead of being impassive, it is helping to shape Buddhism in Australia. Like economic social policy that keeps people in poverty and restricts education in order to qualify for poverty and educational relief, applying Multicultural policy to religion is helping promote duality.

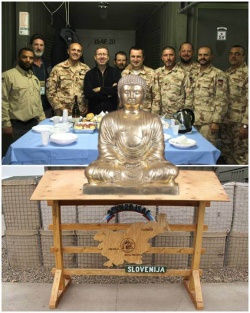

It is promoting identification. The Thai temple, the Japanese temple, the white temple the yellow temple, it is not promoting Dharma; it is rewarding sectarianism and racial exclusivity. I never hear this is a better temple because it is Japanese, or Rinzai is better than Shingon in Japan, but I hear the Chinese way is better or the Thai way is better, or you can’t go here this belongs to us, in Australia. That is corruption not Dharma.

I would suggest Universalism that recognizes different origins and equalities, but does not promote them in the same way as the current model does.

We should not have Buddh-ism in Australia at all, or we should not have Buddhism in Australia.

Buddhism it is often touted proudly in Australia may be the fastest, second fastest or third fastest growing religion in Australia. The fact of that the statement depends on who’s saying it, from what statistical analysis it’s being quoted. The challenge and opportunity fronting us in Australian Buddhism is that we may reform Buddhism as it develops here. It won’t be perfect, but it represents an opportunity to reflect on the forms and the decay within Buddhism and adapt and improve.

We should indentify some early problems with Buddhism so far in Australia such as presenting Buddhism as a faith tied to Ethnic identity, dependent upon that identity. That identity is too easy to use as a shield against reform and a way for charlatan Buddhism to thrive.

We should indentify the difference between innovations made at various points in history and places to the vehicle and that which is superfluous or even harming. Practices that have grown up in certain traditions that are exploitive can be weeded out if we have the commitment to do so.

This identification, debate and action, should take place carefully and hopefully wisely with consideration to what is truly reform as opposed to simple repackaging or rebranding. Removing the forms by itself does not necessarily mean better. If a temple is rebranded as a Dharma centre, or a Monk or nun as a Dharma Teacher or the Kasaya is abandoned for a t-shirt and jeans it does not automatically follow that anything better is being presented by way of practice and we should be aware of that, just as the opposite is also true.

Integrity lies at the heart of Buddhist practice. It is a system only as good as the people who practice it, but it offers the most ethical way to practice when truly practiced.

Zenkie Shibayama, The Gateless Barrier, Zen Comments on the Mumonkan, 2000 Shambala pup. Joshu Zenji Goroku, the record of Zhàozhōu Cōngshěn.

Source

By Ven. Mujyo , Jizoan Zen Temple, Perth

The third International Conference Buddhism & Australia 2014