Eight Wrathful Protectors of Buddhism

The following is an attempt to try to explain the significance of "protectors" in the context of Vajrayana Buddhism. I have to confess with all honesty that my knowledge in this particular subject is extremely limited. Books that I have read regarding "protectors" are usually very vague, brief and even confusing at times. On top of that, I have not personally recieved any extensive teachings from the lineage teachers regarding this matter. And very often, these traditional teachers do not venture into any sophisticated psychological discourse on the significance of these "protectors" - with a few exceptions maybe.

It is important to bear in mind that consistency is not something that is given 100% attention to in Vajrayana. By this I mean that depending on different texts, sources, lineages and teachers, you will get slightly different classifications of things. For example, generally it is said that there are five Buddha-families but occasionally you will get references to a sixth family with Vajrasattva as the lord (in the five family classification, Vajrasattva belongs to the Vajra family with Aksobhya as the lord). Apparently, this six family scheme is rather popular among the Vajrayana lineages in Nepal. Anyway, back to the original point. Therefore, what I write here might not totally agree with what some others might have heard or read. But basically, I think the idea should be the same - that is assuming I am on the right track.

In a particular tradition that I am familiar with, it is said that there are three kinds of protectors. They are dharmapalas, lokapalas and ksetrapalas. Respectively they translate to "dharma-protectors," "world(ly)-protectors" and "field-protectors." Dharma-protectors are those who are highly advanced on the Path. From Vajrayana's point of view, these beings are actually manifestations of the activities of the Buddhas. Some of these beings are considered Buddhas while some are on different levels of the Bodhisattva path. For example, Mahakala and Ekazati are both considered fully enlightened beings while someone like Dorje Lekpa is considered a tenth stage bodhisattva. The worldly-protectors refer to beings who have pledged to protect the teachings and practitioners. These include powerful worldly gods, local spirits, energies and other beings. It is said that sometimes these beings do not even fully accept the teachings of the Buddha. They are in other words as deluded as we are - some of them more, others less. Field protectors are usually associated with very specific places or buildings. In Tibet, families live in the same place and house for hundred of years. As time passes, it is believed that there are certain protectors especially connected with that particular house, clan or family. Spiritually both the worldly and field protectors are much lower than the Dharma-protectors. Both the worldly and field protectors are not particularly related to Dharma in the same way as Dhama-protectors are.

How should we relate to the protectors? I remember reading His Holiness the Dalai Lama's response to a similiar question. His Holiness advised that it is actually sufficient to regard the Triple Gem (Buddha, Dharma and Sangha) as protectors. In his opinion, if one truly takes refuge in the Triple Gem they will be the best protectors one can have. He further explained that protectors are related to Vajrayana practice and only those who are deeply involved with Vajrayana practices should be concerned with the protectors. I suspect that His Holiness' response in this case is spoken for the general audience and in no way indicates that he is not in favor of protector practices. Other teachers also agree that if one really relies on the Triple Gem, protection is guaranteed.

Very briefly, according to Vajrayana, protectors should never be seen as something separate from oneself. Protectors actually have two levels which we can relate with. On the relative level, there are protectors like Mahakala, Palden Lhamo, Dorje Lekpa or Ekazati. There are numerous sadhanas (practices) associated with these protectors. But ultimately, it is our own rigpa (the natural mind which is empty, spacious and open) that is the protector. The sadhanas usually have a structure where the meditator visualizes him or herself as a particular protector. The meditator is reminded again and again that his or her own nature is never separate from the protectors'. Some teachers further explain that in a way, these protectors are simply our own awareness and mindfulness. Because we are beings with both body and mind, it is easier in the beginning for us to focus on some being with a form - the various protectors. By meditating on their enlightened form - the various attributes and ornaments (these are related to different enlightened qualities and activities), one is to actualize these same enlightened qualities in oneself. In a sense, we can say that the protectors are our own awareness and mindfulness appearing in enlightened forms. With right awareness and mindfulness, we will be able to relate to things as they truly are (the wisdom aspect) and carry out the bodhisattva activities (the compassionate aspect). Therefore, the effectiveness of these protectors are directly related to our own level of awareness and mindfulness. I have also heard another teacher explaining that the law of karma is the real protector. Here, he means that if one were to truly understand cause and effect, one will then abstain from performing any negative actions but instead only cultivate good.

Perhaps on a more advance level, the Dharma-protectors are related to different forms and levels of energies. These energies are said to be latent in us. By relating to a particular protector, one learns how to channel up a particular energy and to deal with it in an enlightened way. Because energy is simply energy (with negative and positive potentials), there is always a chance of not knowing how to deal with a certain energy that has been aroused through practice. Or perhaps the means of arousing that energy is misused. This is when it is believed that negative effects will occur. This effect might not only affect the practitioner himself but might include other as well. Therefore, some teachers are extremely cautious when it comes to protector practices. In traditional language, protector's practice is something that one does only if one is certain that one can fulfill all the commitments (samaya or damtshig) related to that practice. Unlike practices like Chenrezig meditation or Tara, it is said that when the protector practice is done wrongly or is not done consistently, the protectors will get extremely "wrathful." These protectors are guardians of the different practices. It is also said that protectors are there to make sure that the purity of the lineage is protected. And to do that, they guard the practices of the practitioners. It is not uncommon to hear people saying that when they became lazy in their practice or got distracted, something mysterious or supernatural happened that pulled them back into the Path again! And devout Tibetans will straightaway acknowledge the protectors for fulfilling their duties. There are also stories of protectors who guard termas - hidden "treasures" (teachings, ritual objects etc, that have supposedly been hidden by masters like Padmasambhava to be retrived in latter days to benefit people). Some of these protectors are even believed to fiecely guard these termas so that if the wrong people get these termas, they might be destroyed or the termas will simply vanish. These protectors are usually not Dharma-protectors but some worldly protectors.

Therefore, on the relative level, these protectors are treated like independent beings who have pledged to protect the Dharma (but since the ultimate and relative can never be taken as distinct, one is always reminded of the ultimate protector - one's own natural mind). Different lineages, teachers and practices have different special protectors. For example, Palden Lhamo and Dharmaraja is particularly associated with the Gelugpas. For the Kagyupas, Mahakala is especially significant. Different aspects of Mahakala (two-armed, four-armed, six-armed, female aspects) are practised by the Sakyas, Gelugs, Kagyus and Nyingmas. In the Drikung-Kagyu (one of the major sects in the Kagyu school), Achi Chokyi Drolma is a protector intimately related to members of this lineage. Milarepa himself is related to the five protector goddesses of Tibet - known as the Tseringmas. Among the Nyingmapas, Ekazati, Rahula and Dorje Lekpa are protectors very closely related to Dzog-chen. The famous deity of the Nechung oracle is the personal protector of the Dalai Lamas. Various elaborate rituals and sadhanas are performed to these protectors in the lives of practitioners. There are certain monasteries that have protector practices carried out 24 hours a day for 365 days a year. If I am not mistaken, there are a group of monks specially charged with the task of performing protector practices for the welfare of His Holiness the Dalai Lama in particular, and the live of the Dharma in general.

So... if I have not totally confused my readers, I hope some of you will at least get a faint idea of what protectors are. If there is anyone out there that have further knowledge and experience that can be shared, do contribute! Call me a conservative, but part of the problem with trying to explain protector practice is that I am not sure what I should write and what I shouldn't. IMHO, protectors can be easily misunderstood. They can be easily seen as spiritual policeman that are out there to get you if you misbehave. And lots of supersitions can come up from this kind of understanding - this is the last thing that I am trying to do. If I have to summarize the significance of protectors very briefly, in say one or two sentences, the following will be it:

"Protectors, like other Buddhas and dieties related to one's practice, should NEVER be seen as separate from one's natural mind, one's rigpa. And to be mindful at all times of cause and effect is perhaps the most direct protector one can get."

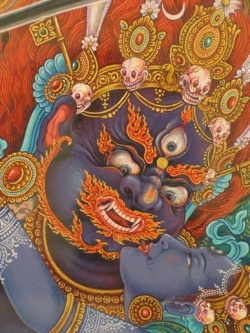

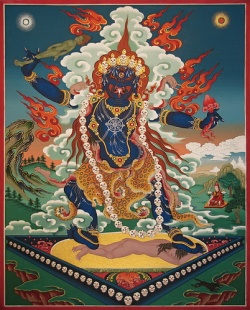

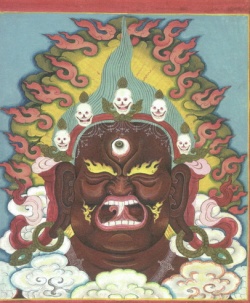

Dharmapalas grimace from Vajrayana Buddhist art, and their sculpted, threatening forms surround many Buddhist temples. From their looks you might think they are evil. But dharmapalas are wrathful bodhisattvas who protect Buddhists and the Dharma. Their terrifying appearance is meant to frighten forces of evil. The eight dharmapalas listed blow are considered the "principal" dharmapalas, sometimes called “Eight Terrible Ones." Most were adapted from Hindu art and literature. Some also originated in Bon, the indigenous pre-Buddhist religion of Tibet, and also from folk tales.

Mahakala is the wrathful form of the gentle and compassionate Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva. In Tibetan iconography he is usually black, although he appears in other colors as well. He has two to six arms, three bulging eyes with flames for eyebrows, and a beard of hooks. He wears a crown of six skulls.

Mahakala is the protector of the tents of nomadic Tibetans, and of monasteries, and of all Tibetan Buddhism. He is charged with the tasks of pacifying hindrances; enriching life, virtue and wisdom; attracting people to Buddhism; and destroying confusion and ignorance.

Yama is lord of the Hell Realm. He represents death.

In legend, he was a holy man meditating in a cave when robbers entered the cave with a stolen bull and cut off the bull's head. When they realized the holy man had seen them, the robbers cut off his head also. The holy man put on the bull's head and assumed the terrible form of Yama. He killed the robbers, drank their blood, and threatened all of Tibet. Then Manjushri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom, manifested as Yamantaka and defeated Yama. Yama became a protector of Buddhism.

In art, Yama is most familiar as the being holding the Bhava Chakra in his claws.

Yamantaka is the wrathful form of Manjushri, Bodhisattva of Wisdom. It was as Yamantaka that Manjushri conquered the rampaging Yama and made him a protector of the Dharma.

In some versions of the legend, when Manhushri became Yamantaka he mirrored Yama's appearance but with multiple heads, legs and arms. When Yama looked at Yamantaka he saw himself multiplied to infinity. Since Yama repesents death, Yamantaka represents that which is stronger than death.

In art, Yamantaka usually is shown standing or riding a bull that is trampling Yama.

Hayagriva

Hayagriva is another wrathful form of Avalokiteshvara (as is Mahakala, above). He has the power to cure diseases (skin diseases in particular), and is a protector of horses. He wears a horse's head in his headdress and frightens demons by neighing like a horse.

Vaisravana

Vaisravana is an adaptation of Kubera, the Hindu God of Wealth. In Vajrayana Buddhism, Vaisravana is thought to bestow prosperity, which gives people freedom to pursue spiritual goals. In art, he is usually corpulent and covered in jewels. His symbols are a lemon and a mongoose, and he also is a guardian of the north.

Palden Lhamo

Palden Lhamo, the only female dharmapala, is the protector of Buddhist governments, including the Tibetan government in exile in Lhasa, India. She is also a consort of Mahakala. Her Sanskrit name is Shri Devi.

Palden Lhamo was married to an evil king of Lanka. She tried to reform her husband, but failed. Further, their son was being raised to be the destroyer of Buddhism. One day while the king was away, she killed her son, drank his blood and ate his flesh. She rode away on a horse saddled with her son's flayed skin.

The king shot a poisoned arrow after Palden Lhamo. The arrow struck her horse. Palden Lhamo healed the horse, and the wound became an eye.

Tshangspa Dkarpo

Tshangspa is the Tibetan name for the Hindu creator god Brahma. The Tibetan Tshangspa is not a creator god, however, but more of a warrior god. He usually is pictured mounted on a white horse and waving a sword.

In one version of his legend, Tshangspa traveled the earth on a murderous rampage. One day he attempted to assault a sleeping goddess, who awoke and struck him in the thigh, crippling him. The goddess's blow transformed him into a protector of the dharma.

Begtse

Begtse is a war god who emerged in the 16th century, making him the most recent dharmapala. His legend is woven together with Tibetan history:

Sonam Gyatso, the Third Dalai Lama, was called from Tibet to Mongolia to convert the warlord Altan Khan to Buddhism. Begtse confronted the Dalai Lama to stop him. But the Dalai Lama transformed himself into the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. Witnessing this miracle, Begtse became a Buddhist and a protector of the Dharma.

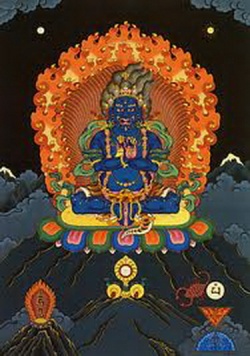

Ekajaṭī or Ekajaṭā, (Sanskrit; Tibetan: ral chig ma. English: One Braid of Hair), also known as Māhacīna-tārā,[1] one of the 21 Taras, is one of the most powerful and fierce goddesses of Indo-Tibetan mythology. According to Tibetan legends she is an acculturation of the Bön goddess of heaven, whose right eye was pierced by the tantric master Padmasambhava as he banished her. Ekajati is also known as 'Blue Tara'. She is generally considered one of the three principal protectors of the Nyingma lineage, along with Rāhula and Vajrasādhu.

Often she appears as liberator in the mandala of Green Tara. Along with that her ascribed powers are removing the fear of enemies, spreading joy and removing personal hindrances on the path to enlightenment.

Sanskrit: Acala Chinese: 不動明王

Búdòng Míngwáng Japanese: 不動明王

Fudō Myōō Mongolian: Хөдөлшгүй Tibetan: མི་གཡོ་བ Information Venerated by: Vajrayana Attributes: Immovable One

Portal:Buddhism

In Vajrayana Buddhism, Ācala (alternatively, Achala or Acalanātha (अचलनाथ) in Sanskrit) is the best known of the Five Wisdom Kings of the Womb Realm. He is also known as Ācalanātha, Āryācalanātha, Ācala-vidyā-rāja and Caṇḍamahāroṣaṇa. The Sanskrit term ācala means "immovable"; Ācala is also the name of the eighth of the ten stages of the path to become a bodhisattva. His siddham seed-syllabe is "hāṃ".

Ācala is the destroyer of delusion and the protector of Buddhism. His immovability refers to his ability to remain unmoved by carnal temptations. Despite his fearsome appearance, his role is to aid all beings by showing them the teachings of the Buddha, leading them into self-control.

He is seen as a protector and aide in attaining goals. Shingon Buddhist temples dedicated to Ācala perform a periodic fire ritual in devotion to him.