Clinging to rites and rituals

Clinging to Rites and Rituals ;

By Gloria Taraniya Ambrosia

Several years ago, during a group practice interview at a ten-day vipassana retreat I was teaching, the topic of discussion turned toward realizing nibbana. As the interview progressed, one fellow in the group became increasingly agitated. Finally, when he was unable to contain himself any longer, he blurted out: “Okay.

Let’s cut to the chase. Who do I have to know? And where do I have to go?” Silabataparamasa, one of three defilements uprooted at the first stage of enlightenment, is defined as holding firmly to the view that through rules and rituals, rites, ceremonies and practices one may reach purification. Here, we aren’t just talking about incantations and rituals in the usual sense. Silabataparamasa also includes bhavana, or meditation practice. In essence, we think that our freedom is found in getting good at doing the meditation practice or doing it out of some sense of obligation or righteousness without reflecting accurately on what it is all about. Thus, we fail to experience what is possible through our practice.

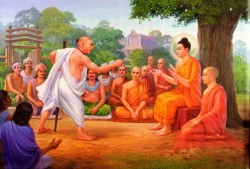

Clinging to a Tradition Silabataparamasa can manifest as an overzealousness about selecting the right teacher, form or tradition in which to practice. It’s as if we think, “If I could just find the right teacher, travel to the right corner of the universe, then I’d reach the goal. It’s all out there somewhere, and I just have to find it and align myself with it.” We can spend many years traveling to different meditation centers, trying out different traditions. We can intellectualize and even argue about the whats and wherefores of each one, but we never get around to applying ourselves in any of them. In one of the suttas, Magandiya asks the Buddha how one realizes inner peace. The Buddha says that it is only by taking tradition as the means and not grasping it as an end in itself that one realizes inner peace. When practiced correctly, all forms of Buddhist practice lead to freedom. Our task is to find the form that speaks to us and then to apply ourselves to it wholeheartedly. Clinging to Methods and Techniques Have you ever come away from a sitting with the smug feeling that the practice is going well because you were able to sit upright unflinchingly for the hour? Silabataparamasa also involves putting undue emphasis on developing the methods or techniques of practice, becoming skilled at using the tools without fully recognizing that tools are tools, not the goal. On a recent trip to Thailand, I visited a monastery in the central part of the country. High on the walls of the bamboo and grass Dhamma hall the resident monks had hung sepia-stained photographs of famous Thai masters of the last century.

Of course, it was inspiring to see so many arahants in one place, but what impressed me most was the fact that none of them had particularly good posture. Thai meditation master Ajahn Lee said that sometimes people think they are practicing meditation but all they are doing is sitting like a post. We can look the part, can’t we? But how we look or how skilled we become at applying the methods of practice doesn’t say anything about how well the meditation is going. We may be able to sit perfectly still for an hour, but all the time we may be daydreaming or thinking about things. We may watch each inhalation and exhalation but fail to contemplate the impermanent, unsatisfactory and selfless nature of phenomenon. We may be able to keep coming back to the breath but neglect to notice the craving or aversion that took us away.

Thus, we never internalize the Dhamma for ourselves. We never actually experience freedom, just skill at handling the tools of practice The message here is to give some thought to how we understand the tools of practice. For example, why do we go on retreat? Is it to escape from the busyness or harshness of life? If we find ourselves mourning the loss of stillness when the retreat is over, we may be guilty of confusing the raft for the other shore. Do we think there is something magical about sitting or that something is going to happen if we just do it long enough? If so, we’ve 3 probably left many a retreat with a feeling of disappointment. Retreat is a special environment. We enjoy the luxury of having an extended period of time during which we can train ourselves to stand back from experience. When we do this long enough, and well enough, we lose some of our preoccupation with the content of our lives and we gradually untangle the web of confusion about what constitutes happiness and suffering. Retreat is simply a way to apply ourselves to this enterprise in a very deliberate way. But the point is to become able to get up from the cushion and live life with greater skill and understanding, less craving and ignorance, and, therefore, less suffering.

The Buddha was quite clear on this. He instructed us to apply ourselves in all four postures and in all our activities throughout the day—not just while we are sitting or on retreat. It’s a 24/7 kind of thing. If we don’t see this, we run the risk of compartmentalizing the formal practice when we would dearly benefit from seeing that all life is practice. Clinging to Ideas about Practice Perhaps the subtlest form of attachment to meditation is clinging to our ideas about it. We hear the meditation instruction and fill our heads with notions about what it is and what we are trying to experience. In the beginning, we really have no idea what mindfulness and concentration are. But that doesn’t stop us from thinking we do! I can recall a time when I was on a long retreat at IMS, being ever so mindful. I was quite confident that anyone who noticed me walking through the dining hall would know I was a very good yogi. One day, as I closed the door to my room behind me, I let out a huge sigh of relief. This really got my attention! Suddenly I could see that for the entire retreat I had been trying to live up to my idea of what it looks like to be mindful.

What if mindfulness and concentration are not what we think they are? What if thinking about them and trying to make ourselves experience them are the chief obstacles to actually abiding in them? There’s a big difference between trying to be mindful and concentrated and actually being so. We need to lose the barrier that the “trying” sets up and settle into now. Early on, we may not see that our practice is driven by self-view. We want to get somewhere, achieve something, but this orientation puts us outside the very truth we are trying to realize. There’s always me and it, me and my practice, me and the states I am trying to become. Anything that we are trying to become is never realized. We only begin to enjoy the fullness of freedom as self-view weakens and we are content to just be and know what is happening. Perhaps it can’t be any other way. We come to practice filled with self-absorption. It takes time for that to wear down. At some point, we begin to lose the sense of self as the one who is doing the practice. We stop trying to “become” concentrated and mindful and instead look for the experience of relaxed awareness in each moment. With this little shift in perspective, relaxed awareness becomes less a skill that we are trying to develop and more an experience into which we settle.

From this new vantage point, the Dhamma can’t help but reveal itself to us. The great Thai Forest master Ajahn Mun said that Dhamma will not serve us well if all we do is comply with rules or follow directions. Understanding the Buddha’s teaching on clinging to the meditation practice can help us break free of our attachments to forms and traditions, methods and techniques, and ideas and notions about practice so that we can see directly what constitutes our suffering, how we got there, how we let go, and how it feels to be free. Gloria Taraniya Ambrosia has been a Dhamma teacher since 1990. She is a student of the western forest sangha, the disciples of Ajahn Sumedho and Ajahn Chah, and is a Lay Buddhist Minister in association with Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery in California. Taraniya will be leading a Mid America Dharma residential retreat, October 25-28, 2007 in the St. Louis area. The topic will be the Sattipatana Sutta.