Life of the Buddha

by Bro. Chan Khoon San

1. The Birth

In the seventh century BC, the northern part of India was divided into sixteen principal states or mahajanapadas, eight of which were kingdoms and the remaining republics. The names of these states are listed in Anguttara I, 213 and Vinaya Texts 2, 146. Among the kingdoms, the most powerful were Magadha and Kosala. According to Rhys Davids, Magadha occupied the district now called Bihar and had its capital at Rajagaha. In the Buddha’s time, it had eighty thousand villages under the rule of King Bimbisara and afterwards, his son Ajatasattu. It covered an area of 300 yojanas or about 2400 miles in circumference. The Kosalas were the ruling clan in the kingdom whose capital was Savatthi that is now part of the ruins called Sahet-Mahet near Balrampur in Uttar Pradesh. Their ruler was King Pasenadi. To the north across the present Indo-Nepalese border, was the little Sakyan republic, a vassal state of Kosala. Its chief was Suddhodana and he had his capital at Kapilavatthu.

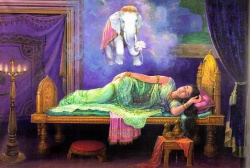

According to the Theravada tradition, the Buddha was born on the full-moon day of Wesakha (late April-May) in 623 BC, although this date is disputed by other traditions (Note 1). His mother was Mahamaya Devi, chief consort of King Suddhodana. Already fifty-six years old (Note 2) and in the final stage of pregnancy carrying the Bodhisatta or future Buddha for ten full months, she was traveling in state to her parents’ home in Devadaha to deliver her first child in keeping with the ancient tradition of her Koliyan clan. Along the way, the entourage passed Lumbini Garden, a pleasure grove of Sala trees, which were then in full bloom. Seeing the immense splendour, she decided to stop there and admire the flowering trees and plants. Soon she began to experience the unmistakable signs of impending birth. Quickly she summoned her female attendants to cordon off the area with curtains. Then holding on to the branch of a Sala tree with her right hand for support, she gave birth to the Bodhisatta while standing up.

In 249 BC, the great Mauryan Emperor Asoka (c. 273-236 BC) visited Lumbini as part of his pilgrimage to the sacred Buddhist places. To commemorate his visit, he built a stone pillar that bore an

inscription in Brahmi script to record the event for posterity. The inscription engraved in five lines reads (Translation):

“Twenty years after his coronation, King Piyadassi, Beloved of the Gods, visited this spot in person and worshipped at this place because here Buddha Sakyamuni was born. He caused to make a stone (capital) representing a horse and he caused this stone pillar to be erected. Because the Buddha was born here, he made the village of Lumbini free from taxes and subject to pay only one-eighth of the produce as land revenue instead of the usual rate.”

After the Muslim conquest of northern India during the 12th century AD that led to the indiscriminate pillaging and desecration of Buddhist shrines and monasteries, Lumbini was abandoned and eventually engulfed by the tarai (forests). In 1886, the German archeologist, Dr. Alois A. Fuhrer, while wandering in the Nepalese tarai in search of the legendary site, came across a stone pillar and ascertained beyond doubt that it was indeed the birthplace of the Buddha. The Lumbini Pillar (or Rummindei pillar) stands today majestically proclaiming that here the Buddha was born.

2. The Prediction

When the good news reached the capital of Kapilavatthu, there was great rejoicing among the people over the birth of their new-born prince. An ascetic named Asita, also known as Kaladevila the Hermit, being the royal tutor visited the palace to see the royal baby. The overjoyed King brought the child to him to pay reverence, but to the King’s surprise, the child’s feet turned and planted themselves on the matted locks of the ascetic’s head. The ascetic, realizing this astonishing and extraordinary power and glory of the Bodhisatta, instantly rose from his seat and saluted him. Witnessing the marvelous scene, the King also bowed down before his own son.

Asita was an expert in distinguishing the marks of greatness and as soon as he examined the child, he confidently proclaimed the child’s future supremacy among mankind. Then seeing his own impending death, tears came to his eyes. The Sakyans, seeing him cry, thought that misfortune would befall on the prince. But Asita reassured them that the prince’s future was secure, as he would surely become a Buddha. He was sad because he would die soon and be reborn in a Formless Realm thereby missing the opportunity to meet the Buddha and listen to His Dhamma.

In order to ensure that someone in his family would not miss this rare opportunity, he related his prediction to his nephew Nalaka. On Asita’s advice, Nalaka renounced the world and when the Bodhisatta attained Supreme Enlightenment thirty-five years later, Nalaka came to see the Buddha to ask some questions. After listening to the Buddha’s answers, Nalaka became an Arahant. A full account of Asita’s prediction and Nalaka’s meeting with the Buddha is given in the Nalaka Sutta of the Sutta Nipata (Group of Discourses).

Five days after the Bodhisatta’s birth, the king held a ceremony to choose a suitable name for the newborn prince. According to the Jataka Commentaries, many learned Brahmins were invited to the Naming Ceremony. Among them were eight experts who could foretell the child’s future just by examining the marks and characteristics of his body. Seven of them raised two fingers to indicate that the child would grow up to become either a Universal Monarch or a Buddha. But the eighth, Sudatta of the Kondanna clan who was the youngest and who excelled the others in knowledge, raised one finger and confidently declared that the prince would renounce the world and become a Buddha. Consequently the Brahmins gave him the name of Siddhattha meaning “wish- fulfilled”. His family name was Gotama. On the seventh day, Prince Siddhattha’s mother died. Her younger sister, Maha Pajapati Gotami who was also married to King Suddhodana became his foster mother.

3. The Ploughing Ceremony

During the Buddha’s time, the main economic activity of his country was farming. As such, a festival was held every year to promote agriculture whereby the King and his noblemen would lead the common folk in ploughing the fields to prepare them for planting. On the appointed day, the King took his young son along, accompanied by the nurses to take care of the child. Placing the child on a couch with a canopy overhead under the cool shade of a solitary rose-apple tree to be cared for by the nurses, the King went to participate in the Ploughing Festival. At the height of the festival, the nurses became distracted by the gaiety and abandoned their posts to watch the spectacle.

Left alone, instead of crying or running after the nurses, the Bodhisatta sat cross-legged on the ground and concentrating on the inhaling and exhaling of his breath, achieved one-pointedness of mind by which he developed the First Jhana (mental absorption). He must have been absorbed in this ecstatic concentration for a long time because when the nurses realized their mistake, it was past noon. Rushing back to the rose-apple tree, they were amazed to see the child sitting cross-legged in deep meditation. On hearing of this remarkable event, the King hurried to the scene and seeing the miracle, he saluted his son, saying, “This, dear child, is my second salutation.” Many years later, after struggling for six years in search of Enlightenment, the memory of this childhood experience convinced the Bodhisatta to abandon the path of self-mortification by recognizing that this indeed was the way to Enlightenment.

4. Prince Siddhatta’s Youth

Although the Pali Scriptures provide little information about the Bodhisatta’s early years, one can surmise that during his boyhood, he would have studied under Brahmin tutors just like his father before him. Under them he would have studied together with the

other Sakyan princes all the Brahmanical literature including the Vedas (scriptures), Negamas (codes), Puranas (mythology), Itihasas (history) and others. This is borne out in the suttas that reveal the Buddha’s familiarity and insight of Brahmin codes and lore. As a member of the warrior caste (khattiya), he was specially trained in the art of warfare excelling in archery and dexterity skills.

Prince Siddhatta grew up in great comfort and luxury. In Anguttara Book of Threes, 38, the Buddha described the luxuries he was showered upon by his father during his youth. He was delicately nurtured and wore the best clothes made from Kasi silk. Day and night, a white umbrella was held over him to shelter him from heat and cold, dust or chaff or dew. He had three palaces; one for the winter, one for the summer and one for the rainy season. In the rains palace, female minstrels were provided for his entertainment. For the four months of the rains, he never went down to the lower palace. Though meals of broken rice with lentil soup were given to the servants and retainers in other people’s houses, in his father’s house white rice and meat were given to them.

When Prince Siddhattha reached sixteen years of age, his father decided to install him on the throne and arrange for his marriage. As soon as word went out that King Suddhodana was looking for a princess to marry his son, the Sakyan aristocrats made derogatory remarks saying that although the prince was handsome, he did not possess any craft that would enable him to support a family. Thereupon, the Bodhisatta gave a spectacular display of his dexterity and archery skills, which so impressed his royal relatives that they all sent their own daughters beautifully dressed and adorned for him to choose as his bride. Among the Sakyan princesses, the one chosen to be his consort was his beautiful cousin, Princess Yasodhara whose maiden name was Bhaddakaccana, also of the same age. She was the daughter of the Koliyan ruler of Devadaha kingdom, Suppabuddha (his mother’s brother) and Queen Amita (his father’s sister). She earned the name of Yasodhara because of her pristine fame and great retinue (Yaso = great retinue and repute, dhara = bearer). After his happy marriage, he led a luxurious life, blissfully unaware of the vicissitudes of life outside the palace gates.

5. The Four Signs and the Great Renunciation

With the march of time, the Bodhisatta became increasingly disenchanted with life in the palace and he would seek solace by going out to visit the royal garden. On four occasions, while riding to the royal garden, he encountered successively the strange sights of a decrepit old man, a diseased man, a corpse and a serene-looking ascetic. The first three sights brought him face to face with the stark realities of the true nature of existence. They are called “samvega nimitta”, signs that give rise to a sense of religious urgency. As he contemplated on them, seeing that he too was not immune from ageing, sickness and death, the vanity of youth, health and life entirely left him. The last sight provided a ray of hope for a means of escape from the suffering of existence. It is called “padhana nimitta”, sign that gives rise to a sense of meditative exertion in order to escape from old age, sickness and death.

When King Suddhodana came to know of these encounters, he became worried that his son would renounce the secular life as predicted by the royal astrologers. To prevent his son from leaving the royal life, he built high walls around the palace, fitted massive doors at the city gate, and increased the strength of guards, attendants and dancing girls to look after the prince. But the Bodhisatta’s samvega (religious urgency) had been aroused. Sensual pleasures no longer appealed to him. Realizing the futility of sensual pleasures so highly sought after by ordinary people and the value of renunciation that the wise take delight in, he decided to renounce the world in search of the Deathless. It was with this deep sense of religious urgency that the Bodhisatta received the news that a son had been born to him. Normally an ordinary father would have rejoiced at it. But the Bodhisatta, having made the decision to renounce the world after much deliberation, saw it as an impediment and remarked, “An impediment (rahu) has been born; a fetter has arisen.” The king, hearing this, named his grandson, Rahula.

According to the Commentaries, the Great Renunciation took place at midnight on the full moon of Asalha (July/August) when the Bodhisatta was twenty-nine years old. Earlier in the evening, he had been entertained by a female troupe of musicians, dancers and singers but he took no delight in it and fell asleep. Seeing the master asleep, the entertainers stopped the show and started to rest. Very soon, they too fell asleep. When the Bodhisatta awoke, he saw these women sleeping like corpses in a cemetery, their musical instruments and belongings strewn about, some with saliva flowing out of their mouths, some grinding their teeth, some talking confusedly, some snoring, some with their garments in disarray exposing their bodies, their hair loose and tangled. When the Bodhisatta saw the change in them, he was filled with loathsomeness and uttered, “How oppressive it is; how terrible indeed!” His mind was made up, “This very day I must depart from here.” Leaving the palace, he went to the stable and ordered his charioteer Channa to saddle his favourite horse Kanthaka for his departure immediately.

While Channa was making preparations, the Bodhisatta went to the bedroom to have a look at his newborn son before leaving. He saw his wife asleep with her arm resting on the child’s head. He wanted to remove the mother’s hand and cradle his son in his arms but decided against it for fear that it would awaken his wife and jeopardize his plan of renunciation. Knowing that both mother and child would be well taken care of by his father, the Bodhisatta left, vowing to return to see his son again only after attaining Enlightenment. Mounting his horse Kanthaka and letting Channa hold on to the tail, the Bodhisatta rode out of Kapilavatthu by the East Gate and journeyed into the night. They traveled the whole night without stopping and arrived next day on the bank of the Anoma River in the country of the Mallas. Here the Bodhisatta cut off his hair and beard with his sword and handing over his garments and ornaments to Channa, he donned the simple robe of an ascetic. Although Channa wanted to renounce too in order to serve him, the Bodhisatta forbade it and asked him to return to the palace with the horse. But Kanthaka, seeing his master leaving them, died of a broken heart and Channa returned alone to Kapilavatthu to break the news to King Suddhodana.

6. The Search and Struggle for Enlightenment

After becoming an ascetic, the Bodhisatta spent a week at the nearby mango grove called Anupiya before proceeding to Rajagaha to look for a suitable teacher to help him realize his goal. Even when he arrived at Rajagaha where King Bimbisara offered him half the kingdom, he rejected the offer, stating that he wanted to find a way to end old age, sickness and death, promising that he would return after he had found the answer. As a seeker of Truth and Peace, he approached Alara Kalama of Vesali, an ascetic of repute and speedily learnt his doctrine and developed the 7th Arupa Jhana, the Realm of Nothingness, a very advanced stage of concentration. Dissatisfied with Kalama’s system, he left him and approached Uddaka Ramaputta of Rajgir where he mastered his doctrine and attained the highest stage of mundane concentration, namely, the 8th Arupa Jhana, the Realm of Neither Perception nor Non-Perception.

Again he was not satisfied with the results and he left it to pursue his search. He was seeking for Nibbana, the complete cessation of suffering. He found that nobody was competent to teach him what he sought as all were enmeshed in ignorance. Though disappointed, he was not discouraged in seeking for the incomparable state of Supreme Peace. He continued to wander and arrived in due course at Uruvela forest by the banks of the Neranjara River, where he resolved to settle down for his meditation and to achieve his desired goal on his own.

Hearing of his renunciation, Kondanna, the Brahmin who predicted that he would become a Buddha and Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahanama and Assaji, sons of four other sages, also renounced the world to join his company. For six long years, Siddhatta led a superhuman struggle practising all forms of severe austerities. In the Greater Discourse on the Lion’s Roar in the Majjhima Nikaya, the Buddha related to the Venerable Sariputta how he practised the extremes of asceticism, coarse living, scruples and seclusion in dreaded places like forests, groves and cemeteries when he was a Bodhisatta. The Venerable Nagasamala who was standing behind the Blessed One fanning him said that he could feel the hairs on his body standing on ends as he listened to the discourse and wanted to know its name. To

this the Buddha replied that it should be remembered as “The Hair- raising Discourse”. The extreme austerities took a heavy toll on his delicate body. It was almost reduced to a skeleton and resulted in the exhaustion of his energy. He was so emaciated that when he touched his belly skin, he could feel his backbone. He was on the verge of death, having gone beyond any ascetic or Brahmin in the practice of self-mortification. Yet all these proved futile and he began to look for another path to Enlightenment.

He remembered the time during his childhood when he was enrapt in Jhana, secluded from sensual desires. Then following up that memory, there came the recognition that it was the way to Enlightenment. Realizing that Enlightenment could not be gained with an exhausted body, he abandoned self-mortification and adopted the Majjhima Patipada or Middle Path, which is the Path between the two extremes of sensual pleasure and self-mortification. His decision to take some food, however, disappointed the five Ascetics who attended on him. At a crucial time when help would have been most welcome, his only companions left him, but he was not discouraged. After a substantial meal of milk rice offered by Sujata, a generous lady, he sat under the famous Pipal tree at Bodhgaya to meditate with the earnest wish and firm determination not to rise from his seat until he attained Buddhahood.

7. The Enlightenment and the Seven Weeks After

On the eve of Vesakha in 588 BC, while meditating with mind tranquillized and purified, in the first watch of night (6pm-10pm) he developed that supernormal knowledge which enabled him to remember his past lives, thereby dispelling the ignorance with regard to the past. In the second watch (10pm-2am), he developed the clairvoyant supernormal vision, which enabled him to see the death and rebirth of beings thereby dispelling the ignorance with regard to the future. In the last watch (2am-6am), he developed the supernormal knowledge with regard to destruction of defilements and comprehending things as they truly are, realized the Four Noble

Truths, thus attaining Perfect Enlightenment. The famous Pipal tree is now called the Bodhi tree for it was under this tree that Prince Siddhatta attained Sambodhi or Perfect Wisdom. Having in his 35th year attained Buddhahood, that supreme state of Perfection, He devoted the remainder of his life to serve humanity and to lead men by the Noble Eightfold Path to the cessation of all suffering.

After the Enlightenment, for seven weeks the Buddha fasted, and spent His time under the Bodhi tree and in its neighborhood.

1) The whole of the first week, the Buddha sat under the Bodhi tree in one posture experiencing the Bliss of Emancipation.

2) During the second week, as a mark of gratitude to the Bodhi tree that sheltered Him during His struggle for Enlightenment, the Buddha stood gazing at it with unblinking eyes (Animisalocana).

3) During the third week, the Buddha paced up and down on a jewelled promenade (Ratana Cankamana) near the Bodhi tree.

4) The fourth week He spent in a jewelled chamber (Ratanaghara) meditating on the Abhidhamma and rays of six colours emanated from his body. (Note 3)

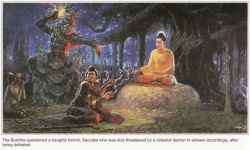

5) The fifth week was spent under the Ajapala Banyan tree in the vicinity of the Bodhi tree. Here He declared the qualities of a true Brahmin in answer to the question by a conceited Brahmin.

6) The Buddha spent the sixth week under the Mucalinda tree. At that time, there arose a great rainstorm with cold winds and gloom for seven days. Thereupon Mucalinda, the Serpent King of the lake, came out and coiled himself around the body of the Buddha and sheltered the Lord’s head with his large hood.

7) The Buddha spent the seventh week under the Rajayatana tree where two merchant brothers, Tapussa and Bhallika from Ukkala (Orissa) offered Him rice cakes and honey. When the Buddha finished His meal, they prostrated themselves before His feet and sought refuge in the Buddha and the Dhamma. Thus, they were the first lay disciples who took the two-fold refuge.

8. The Buddha Propounds the Teaching (Dhamma)

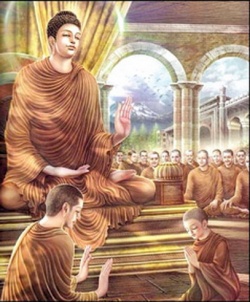

After His meal, the Buddha began to contemplate and was reluctant to teach the Dhamma to the people. He thought that people would not be able to understand His noble and deep teaching for they were shrouded by ignorance. Thereupon, Brahma Sahampati came and invited Him to teach the Dhamma saying that there will be those who could understand the Dhamma. On surveying the world, the Buddha perceived that there were beings that could understand and realize the Dhamma and He accepted the invitation of Brahma Sahampati to teach the Dhamma. The first person that came to His mind was Alara Kalama but a deity informed Him that Alara Kalama had died seven days ago. Then He thought of Uddaka Ramaputta and again a deity informed Him that Uddaka had died the previous evening. Finally He thought of the five ascetics who attended on Him during His struggle for Enlightenment. With His supernormal vision, He perceived that they were staying in Deer Park at Isipatana near Benares (present day Varanasi).

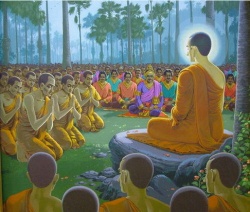

On the 50th day after His Enlightenment, the Buddha proceeded to Benares to expound the Dhamma to his friends, the 5 Ascetics, namely Kondanna, Bhaddiya, Vappa, Mahanama and Assaji. He arrived at the Deer Park in Isipatana on the full-moon day of Asalha, 2 months after Vesakha and delivered His First Discourse, the Dhammacakkkapavattana Sutta or Discourse on Turning the Wheel of Dhamma which led to the Five Ascetics attaining Sotapatti, the first stage of sainthood, and all became monks under the Buddha. Later the Buddha preached the Anattalakkhana Sutta or Discourse on Non-Self, hearing which all attained Arahantship or final stage of sainthood.

The Buddha also succeeded in expounding His Dhamma to a rich young man, Yasa and his fifty-four friends who joined the Holy Order and became Arahants. Yasa’s parents and his wife also attained Sotapatti and became the first lay disciples who took the Threefold Refuge of the Buddha, Dhamma and Sangha. Thus, within a short period of time there were sixty monks, all of them Arahants. Lord Buddha dispatched them in various directions to spread the Dhamma. Lord Buddha himself also left Benares and journeyed to

Uruvela. On the way, He met a group of thirty young noblemen called Bhaddavaggi or the fortunate group because they were princely brothers having a good life. While they were merry-making in the forest, a hired woman ran off with the valuables of one of the brothers. The thirty princes while searching for the woman saw the Buddha. In the encounter, the Buddha succeeded in preaching the Dhamma to them. They were established variously, in the first, second and third stages of sainthood and entered the Order. These monks were half brothers of King Pasenadi of Kosala and as they usually resided in Paveyya City in the western part of Kosala, they were known as the Paveyyaka monks. They realized Arahantship at a later date after hearing the Anamatagga Sutta or Discourse on the Endless Rounds of Existence, while the Buddha was dwelling in Veluvana monastery in Rajagaha. It was on their account that the Buddha allowed monks to hold the Kathina ceremony (Note 4) every year after the rains retreat or vassa.

At that time in Uruvela, there were 3 matted hair ascetic brothers: Uruvela Kassapa, Nadi Kassapa and Gaya Kassapa living separately with 500, 300 and 200 disciples respectively. With much effort and at times using His psychic powers, the Buddha succeeded in convincing them to enter the Order. Knowing that they were all fire-worshippers, the Buddha delivered to them the Adittapariyaya Sutta or Fire Discourse, hearing which all attained Arahantship. Accompanied by His retinue of 1000 Arahants, all former matted hair ascetics, the Buddha proceeded to Rajagaha to meet King Bimbisara in accordance with the promise He made before His Enlightenment. When King Bimbisara and the Brahmin citizens saw the Buddha with Uruvela Kassapa whom they held in high esteem, they were not sure who the leader was. Reading their minds, the Buddha questioned Kassapa who acknowledged the Buddha as His Master by rising in the air and paying homage to the Buddha three times. Later on the Buddha preached the Maha Narada Kassapa Jataka followed by a graduated discourse, at the end of which one hundred and ten thousand Brahmins headed by Bimbisara attained the first stage of sainthood. Later on, King Bimbisara offered his Bamboo Grove (Veluvana) for the use of the Buddha and His disciples, the first gift of a place of residence. The Buddha spent three successive vassas and three other vassas in this famous park.

9. Conversion of Sariputta and Moggallana

Not far from Rajagaha in the village of Nalaka, there lived a very intelligent Brahmin youth named Upatissa also known as Sariputta, scion of the leading family of the village. He had a very intimate friend in Kolita also known as Moggallana, the son of the leading family of another village. Together they had left the luxury of the household life and became ascetics under a teacher named Sanjaya. Very soon, they became dissatisfied with his teaching and returned to their own villages, with the understanding that whosoever discovered the Path of Release should teach the other. It was at this time that the Venerable Assaji, one of the first 5 disciples, was on alms round in Rajagaha. Impressed by his calm and serene manner, Upatissa offered his seat and water to the Venerable Assaji when the latter was having his meal. On being asked by Upatissa to teach him the doctrine, Ven. Assaji uttered a four-line stanza, skillfully summing up the Master’s Teaching of cause and effect:

“Ye dhamma hetuppabhava – tesam hetu tathagato

Aha tesan ca yo nirodho – evam vadi Maha-Samano.”

“Of things that proceed from a cause – their cause the Tathagata has told. And also their cessation -- Thus teaches the Great Ascetic.”

Immediately on hearing half the stanza consisting of two lines, Upatissa attained Sotapatti, the first stage of sainthood. In accordance with the agreement, he returned to his friend Kolita, who also attained Sotapatti after hearing the whole stanza. Accompanied by their followers, the two friends went to see the Buddha and requested for admission into the Order. The Venerable Moggallana attained Arahantship after one week but the Venerable Sariputta passed a fortnight in reviewing and analyzing with insight all levels of consciousness, attaining Arahantship while fanning the Buddha who was giving a discourse to the wandering ascetic Dighanakha. That very evening, the Buddha summoned all His disciples to His presence and conferred the titles of First and Second Chief Disciples of the Sangha respectively on the Venerables Sariputta and Maha Moggallana.

At this, some monks were displeased and complained among themselves that the Buddha should have given the rank of Chief Disciples to those who ordained first such as the five Ascetics or to Yasa and his friends or the thirty Bhaddavaggiya (fortunate) monks or else to the three Kassapa brothers. Instead He had bypassed all those Great Elders and given the title to the ‘youngest monks’ i.e. those who ordained last. When the Buddha came to know of this, He assembled the monks and explained His choice. When Ven. Sariputta and Ven. Maha Moggallana many aeons ago, at the time of Buddha Anomaddassin, were born as the Brahmin youth Sarada and merchant Sirivaddhaka, they made the aspiration to become Chief Disciples. So what the Buddha had done was to give them what they had aspired for, while the other senior monks did not make the aspiration to become Chief Disciples. (Note 5)

10. The Buddha Visits His Birthplace

King Suddhodana knowing that the Buddha was preaching the Dhamma in Rajagaha, dispatched nine courtiers on nine successive occasions to invite the Buddha to Kapilavatthuu but on every occasion, the courtier was converted by the Buddha and attained Arahantship. After the attainment they became indifferent to worldly affairs and so did not convey the message to the Buddha. Finally another courtier Kaludayi, a childhood friend of the Buddha, was chosen to carry the invitation. He agreed to go as he was granted permission to enter the Order. On meeting the Buddha and hearing the Dhamma, he too attained Arahantship but he remembered his promise to the old King and conveyed the message to the Buddha.

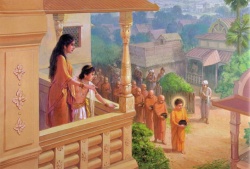

When the Buddha returned to Kapilavatthu, He had to exhibit His psychic powers to subdue the pride of His relatives and elderly Sakyans who did not pay Him due reverence. His father, on seeing the miracles saluted Him for the third time. The Buddha then proceeded to preach to them the Vessantara Jataka. He continued preaching to his father on several occasions and the aged king

succeeded in reaching the 3rd Stage of Sainthood. The Buddha succeeded in persuading His stepbrother Nanda and cousin Ananda to join the Holy Order.

When the Buddha visited the palace, Princess Yasodhara and her son Rahula came to pay their respects and the latter was admitted into the Order though at a tender age of seven years only. When King Suddhodana heard about the ordination of his beloved grandson, he felt aggrieved and requested the Buddha not to approve the ordination of any minor without prior consent of the parents. The Buddha agreed to this request and made it a Vinaya rule. Before he died, King Suddhodana heard the Dhamma from the Buddha and attained Arahantship. He passed away after experiencing the bliss of Emancipation for seven days as a lay Arahant when the Buddha was forty years old. After the death of the king, Maha Pajapati Gotami and Princess Yasodhara joined the Order of Nuns formed by the Buddha and later attained Arahantship.

11. The Buddha’s Ministry

The Buddha’s ministry was a great success lasting for 45 years and was generously supported by many lay disciples, ranging from kings to commoners. His chief male lay-supporter (dayaka) was the millionaire Sudatta, commonly known as Anathapindika (feeder of the poor) who donated the famous Jetavana Monastery at Savatthi where the Buddha spent nineteen rainy seasons and gave many discourses found in the Scriptures. His chief female lay-supporter (dayika) was the Lady Visakha who donated the Pubbarama Monastery in the east of Savatthi where the Buddha spent six rainy seasons. The Buddha was so skillful in His preaching of the Dhamma that He even succeeded in converting the notorious killer Angulimala to join the Order while He was in Savatthi.

In the course of His ministry for forty-five years, the Buddha was indefatigable. He traveled on foot with a company of monks all over

Northern India, from Vesali in the east to Kuru (Delhi) in the west, preaching the Dhamma for the benefit of mankind. Although His motive was pure and selfless, yet He faced strong opposition, mainly from the leaders of other religious sects and the traditional Brahmin caste. Within the Order too, the Buddha also face some problems especially from His cousin and brother-in-law Devadatta, who was always plotting against Him in order to take over the Order but was never successful. In the end, Devadatta left the Order but just before his death, he repented and desired to see the Buddha. Before he could enter Jetavana monastery where the Buddha was residing, he was swallowed into the swampy ground just outside the gate. At the last moment, he took refuge in the Buddha.

12. The Parinibbana and Final Admonition to the Monks

Three months before His Parinibbana (passing away wherein the elements of clinging do not arise again), Lord Buddha relinquished the will to live at the Capala Shrine in Vesali. Summoning all the local monks to the assembly hall of the Gabled House, he delivered his Final Admonition in which he exhorted them to thoroughly learn, develop, practise and propagate those Teachings, which he had direct knowledge in order that the Holy Life may last long. “And what, Bhikkhus, are these Teachings? Verily, they are the Four Foundations of Mindfulness (Satipatthana), the Four Right Efforts (Sammappadhana), the Four Bases of Success (Iddhipada), the Five Faculties (Indriya), the Five Powers (Bala), the Seven Factors of Enlightenment (Bojjhanga), and the Eight Constituents of the Path (Magganga).” (Note: These are the 37 Requisites of Enlightenment that must be developed in order to attain Enlightenment.)

From Vesali, the Buddha took the journey on foot to his final resting place in Kusinara, instructing the monks in the Dhamma along the way. He had His last meal from Cunda the smith, while His last convert was the wandering ascetic named Subhadda to whom the Buddha preached the Lion’s Roar in which He declared the Noble Eightfold Path to be the true way to Nibbana, namely:

“In whatsoever Teaching and Discipline, Subhadda, there is not found the Noble Eightfold Path, neither is there found the true ascetic of the first nor second, third nor fourth degree of saintliness. But in whatsoever Teaching and Discipline, there is found the Noble Eightfold Path, therein is found the true ascetic of the first and second, third and fourth degree of saintliness. Now in this Teaching and Discipline, Subhadda, is found the Noble Eightfold Path; and in it alone is found also the true ascetic of the first and second, third and fourth degree of saintliness.* Devoid of true ascetics are the systems of other teachers; but if, Subhadda, the bhikkhus live righteously, the world will not be destitute of Arahants.” (* i.e. the sotapanna, sakadagamin, anagamin and arahant respectively)

The Buddha’s Parinibbana took place on the full-moon day of Wesakha under the shade of two Sala trees in the Sala Grove of the Mallas. It was His eightieth year in 543 BC. His famous last message to His disciples was: “Behold, O disciples, I exhort you. Subject to decay are all component things. Accomplish all your duties with heedfulness.”

Thus, ended the life of the noblest being the world has ever known. As a man He was born. As an extraordinary man He lived. As a Buddha, He passed away. In the annals of history, no man is recorded as having so consecrated himself to the welfare of all beings, irrespective of caste, class or creed as the Supreme Buddha, endowed with Omniscience and Great Compassion. Although the Buddha is gone, yet the Dhamma that he taught for forty-five years still remains, thanks to the indefatigable efforts of his far-sighted and faithful disciples who codified His Teachings and transmitted them orally over five centuries before they were finally written on palm leaves in the island of Sri Lanka, far away, from its birthplace. The story of how this Dhamma Treasury called the “Tipitaka or Three Baskets” containing the teachings and practices leading to the end of suffering has remained intact and unadulterated, spreading beyond the borders of its narrower home, is a fascinating chronicle that is told in Chapter XVII. It is a living testament of the religious zeal and dedication of the ancient monks in preserving, propagating and perpetuating the Teachings of Lord Buddha, from his Mahaparinibbana till the present day.

13. References

1) A Manual of Buddhism by Ven. Narada Maha Thera.

2) Some Notes on the Political Division of India when Buddhism arose. By T. W. Rhys Davids, Journal of the Pali Text Society

1897 – 1901.

3) The Life of the Buddha – According to the Pali Canon. By

Bhikkhu Nanamoli, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka.

4) The Great Chronicle of Buddhas by the Most Venerable Mingun

Sayadaw Bhaddanta Vicittasarabhivamsa. Yangon, Myanmar.

5) Buddhist Legends translated from Dhammapada Commentary by Eugene Watson Burlingame Part 1, Book I, 8.

6) Last Days of the Buddha (Mahaparinibbana Sutta). By Sister

Vajira, Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka, 1964.

7) Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha -- A New Translation of the Majjhima Nikaya. Translated by Bhikkhu Bodhi and

Bhikkhu Nanamoli. Buddhist Publication Society, Sri Lanka.

14. Explanatory Notes

Note 1: According to the Theravada tradition, the Buddha passed into Parinibbana (Final Passing Away) on the full-moon day of Wesakha (April-May) in 543BC in Kusinara. As he was eighty years old, the year of his birth was 623BC. These dates have been accepted in all Theravada countries as well as the World Fellowship of Buddhists. In the Sangha, monks count the passage of years by the number of vassas or rainy seasons, so the first rainy season (July-October) after Parinibbana is reckoned as Year 1 of the Buddha Era (BE), which means that 543BC is 1 BE. To convert the Gregorian calendar to the Buddhist calendar, just add 544 to the current year e.g. 1956AD was celebrated as the 2500th anniversary of the Buddha Era.

However European scholars in the early 20th century had rejected this chronology after they noted a discrepancy between the Theravadin dating of Asoka’s coronation and the date of that event, which may be calculated from ancient Greek sources, e.g., the Indika written around 300BC by Megasthenes, the Seleucid ambassador to the Mauryan court of Chandragupta, grandfather of Asoka. The Greek sources place Asoka’s

coronation approximately sixty years later than the Pali sources. The year of Parinibbana was recalculated as 483BC and most scholars have accepted this as the correct version. Both versions belong to the so-called

‘long chronology’ because they accept the Theravadin claim that Asoka was consecrated 218 years after Parinibbana.

At a conference held near Gottingen, Germany in 1988, a new breed of scholars proposed another chronology based on the re-interpretation of Acariyaparampara or the lineage of five teachers preceding Ven. Mahinda listed in the Mahavamsa by Geiger. The idea is nothing new. In 1881, T. W. Rhys Davids noted that the period of 236 years for the five teachers prior to the Third Council was too long and proposed a shorter period of

150 years between the Third Council and the Parinibbana. This idea would place the Buddha’s Parinibbana around 400BC instead of 483BC. This re- dating is based on the reasoning that a modern clergyman who ordains a pupil would have been ordained thirty or forty years before; and four such intervals would fill out, not 238 years, but about 150 years; and a similar argument applies with reasonable certainty to the case in point. However this assumption appears to have ignored the fact that the Acariyas (teachers) lived to a ripe old age due to a simple lifestyle and mental purity unlike the modern clergymen. So this new theory appears flawed.

Note: The Acariyaparampara or lineage of teachers provides the number of years or vassas as a monk of each teacher beginning with Ven. Upali (74), Ven. Dasaka (64), Ven. Sonaka (64), Ven. Siggava (76), Ven. Moggaliputta (80) and Ven. Mahinda (60 years).

References:

1) The Dating of the Historical Buddha: A Review Article by L. S. Cousins. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Series 3, 6.1 (1996): 57-63.

2) The Book of the Great Decease by T. W. Rhys Davids in Vol. XI of the

Sacred Books of the East. Clarendon Press 1881.

Note 2: According to the Commentaries, Queen Mahamaya had reached the third portion of the second stage of life when she conceived the Bodhisatta. As the human lifespan then was one hundred years and divided into 3 stages, the length of each stage was 33 years 4 months. Each stage was further sub-divided into 3 portions with each portion representing 11 years. Thus Queen Mahamaya was 55 years 4 months when she conceived. Adding 10 months of pregnancy, she would be 56 years 2 months when she gave birth to the Bodhisatta.

Note 3: The Commentaries explain that when the Buddha contemplated on the Great Patthana or Conditional Relations, his Omniscience found the opportunity to display its extensive brilliance in this all-embracing treatise with its unlimited number of permutations (just as a whale can frolic in the deep ocean but not in a pond). As the Buddha applied his mind to the most subtle and profound points of the Patthana, there arose great rapture in the mind. Because of the rapture, his blood became clearer; because of the clearer blood, his skin became clearer. Because of the clearer skin, rays of different colours emanated from his body and traveled outwards in all directions. Blue light radiated from the blue parts (of the Buddha’s physical frame) such as the hair and pupils of the eye; yellow and golden rays from the skin; white rays from bones, teeth and white portions of the eye; red rays from eyes, flesh and blood. From the various unascertainable parts of the Buddha’s body, rays of light and dark colours and resulting from the mixture of the colours, sparkling and glittering colours shone forth. Thus the six rays of blue, gold, white, red, darkish and glittering colours radiated outwards in the direction of all ten quarters up till today, a time when the Buddha’s Teachings still shines forth.

Note 4: The Paveyyaka monks returned to their city and retired to the forest where they took up ascetic practices or dhutanga, namely: living in the forest (arannakanga), going for alms (pindapatikanga), wearing robes made from rags taken from a dust heap or cemetery (pansukulikanga), wearing only three robes (tecivarikanga). In this way, they passed thirteen whole years. In the end, desiring to see their Master and pay homage, they started on their journey to Savatthi where the Buddha was residing. Since the distance was too far, they had to stop at Saketa, a distance of 6 yojanas or 72 miles from Savatthi, due to the start of the vassa or rains retreat. In spite of their eagerness to see the Buddha, they had to take up residence at Saketa because it was an offence for monks to be away from their residence for more than 3 days during the vassa. As soon as the vassa was over, they immediately resumed journey although the rains had not stopped. Travelling through the countryside in the rain and mud, their robes became soaked and soiled when they arrived at Savatthi to pay homage to the Buddha. Seeing their exhaustion and uncomfortable position, Buddha was filled with compassion and gave permission to hold the Kathina ceremony. The Kathina, literally ‘hard’ refers to the stock of cloth presented by the faithful to be made up into robes for the use of the Sangha during the ensuing year. The whole of this cotton cloth must be dyed, sewn together and made into robes and then formally declared to be not only common property of the Sangha but also available for immediate distribution, all on one and the same day.

Note 5: According to the Dhammapada Commentary (Buddhist Legends Book I, Story 8), the Chief disciples made their aspiration one asankheyya and 100,000 world cycles ago (Chapter VIII, 10), during the Dispensation of the Buddha Anomadassin. Thereafter they had to fulfill the Ten Paramis (Perfections) over that immense period of time before becoming Chief Disciples in the Dispensation of the Buddha Gotama. To become a Great Disciple (Maha Arahant), the aspirant has to fulfill the Perfections for

100,000 world cycles.

One hundred thousand world cycles ago, Ven. Kondanna had made the aspiration to be the first to realize the Dhamma when he performed dana for seven days to the Buddha Padumuttara. Ninety-one world cycles ago, he was born as a farmer named Culakala and enjoyed offering his first crop to the Buddha Vipassi, which he did nine times. However his elder brother Mahakala had no such desire but in the end he also gave alms. In the present Dispensation, Culakala was born as Kondanna and was the first to realize the Dhamma when our Lord Gotama Buddha preached the First Sermon in the Deer Park at Isipatana near Sarnath while his brother Mahakala was born as the wandering ascetic Subhadda and was the last to be ordained by the Buddha. He attained Arahantship after the Buddha had passed into Parinibbana in Kusinara.

Ven. Yasa and his fifty-four friends aspired to Arahantship many world cycles ago in the presence of a certain Buddha and they also performed many meritorious deeds.

The thirty Bhaddavaggiya monks too aspired to Arahantship in the presence of former Buddhas. Later on before the appearance of the Buddha, they were born as thirty drunkards. Hearing the admonition by the Bodhisatta in the Tundila Jataka, they turn over a new leaf and observed the five precepts for 60,000 years.

Aspiring to Arahantship, the Kassapa brothers performed meritorious deeds. Ninety-two world cycles ago, there appeared during that world cycle, two successive Buddhas, Tissa and Phussa. The Kassapa brothers were brothers of the Buddha Phussa and taking their thousand followers performed dana and observed the Ten Precepts for three months. After death, they were reborn as devas and spent ninety-two world cycles in successive rebirths in the deva realms. Thus the three brothers, aspiring to Arahantship performed meritorious deeds during that period and achieved what they aspired for.