Tathāgatagarbha Sutras

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras are a group of Mahāyāna sūtras that present the original concept of Buddha-nature, i.e. the original vision of the Buddha-nature as an ungenerated, unconditioned and immortal Buddhic element within all beings.

Tathāgatagarbha sūtras include the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra, Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra, Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra and the Angulimaliya Sūtra. Related ideas are in found in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra and Avataṃsaka Sūtra. Another major text, the Awakening of Faith, was originally composed in China.

Nomenclature and etymology

The Sanskrit term "tathāgatagarbha" may be parsed into tathāgata ("the one thus gone", referring to the Buddha) and garbha ("root/embryo"). The latter has the meanings: "embryo", "essence"; whilst the former may be parsed into "tathā" ("[s]he who has there" and "āgata" (semantic field: "come", "arrived") and/or "gata" ("gone").

For the various equivalents of the Sanskrit term "tathāgatagarbha" in other languages (Chinese, Japanese, Vietnamese), see Glossary of Buddhism, "tathagatagarbha"

Development of the concept

Main article: Buddha-nature

Luminous mind in the Nikāyas

In the Anguttara Nikāya, the Buddha refers to a "luminous mind".

The canon does not support the identification of the "luminous mind" with nirvanic consciousness, though it plays a role in the realization of nirvana. Upon the destruction of the fetters, according to one scholar, "the shining nibbanic consciousness flashes out of the womb of arahantship, being without object or support, so transcending all limitations."

Tathagatagarbha and Buddha-nature

Though the tathagatagarbha and the Buddha-nature have not exactly the same meaning, in the Buddhist tradition they became equated. In the Angulimaliya Sūtra and in the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra the terms "Buddha-nature" (Buddha-dhātu) and "tathāgatagarbha" are synonyms.

All are agreed that the tathāgatagarbha is an immortal, inherent transcendental essence or potency and that it resides in a concealed state (concealed by mental and behavioural negativities) in every single being, even the worst - the icchantika.

Although attempts are made in the Buddhist sutras to explain the tathāgatagarbha, it remains ultimately mysterious and allegedly unfathomable to the ordinary, unawakened person, being only fully knowable by perfect Buddhas themselves.

The tathāgatagarbha itself needs no cultivation, only uncovering or dis-covery, as it is already present and perfect within each being:

An unknown treasure exists under the home of a poor person that must be uncovered through removing obstructive dirt, yielding the treasure that always was there. Just as the treasure already exists and thus requires no further fashioning, so the matrix-of-one-gone-thus [i.e. the tathāgatagarbha], endowed with ultimate buddha qualities, already dwells within each sentient being and needs only to be freed from defilements.

The tathāgatagarbha is the ultimate, pure, ungraspable, inconceivable, irreducible, unassailable, boundless, true and deathless quintessence of the Buddha's emancipatory reality, the very core of his sublime nature.

Texts

Overview

Key texts associated with this doctrine, written in India, are the

Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra (200-250 CE)

Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra (2rd century CE )

Anunatva Apurnatva Nirdeśa

Angulimaliya Sūtra

Ratnagotravibhāga, a compendium of Tathāgatagarbha-thought

Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra (ca. 200 CE), very influential in Chinese Buddhism

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (3rd century CE), integrating Tathāgatagarbha and Yogacara

Awakening of Faith in the Mahāyāna (6th century CE), a śāstra (commentary) written in China

Comparing the tradition of Tathāgatagarbha sūtras to the Yogācāra and Mādhyamaka schools, Paul Williams writes that this collection appears to have been less prominent in India, but became increasingly popular and significant in Central Asian Buddhism and East Asian Buddhism.

Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra (200-250 CE)

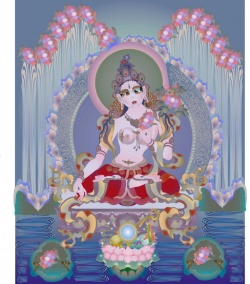

The Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra presents the tathāgatagarbha as a virtual Buddha-homunculus, a fully wisdom-endowed Buddha, "a most victorious body ... great and indestructible", inviolate, seated majestically in the lotus posture within the body of each being, clearly visible only to a perfect Buddha with his supernatural vision. This is the most "personalist" depiction of the tathāgatagarbha encountered in any of the chief Tathāgatagarbha sutras and is imagistically reminiscent of Mahāyāna descriptions of the Buddha himself sitting in the lotus posture within his own mother's womb prior to birth: "luminous, glorious, gracious, beautiful to see, seated with his legs crossed" and shining "like pure gold ..."

Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra (2rd century CE)

Some of the earliest and most important Tathāgatagarbha sūtras have been associated by scholars with certain early Buddhist schools in India.

Brian Edward Brown dates the composition of the Śrīmālādevī Siṃhanāda Sūtra to the Īkṣvāku Dynasty in the 3rd century CE, as a product of the Mahāsāṃghikas of the Āndhra region (i.e. the Caitika schools). Wayman has outlined eleven points of complete agreement between the Mahāsāṃghikas and the Śrīmālā, along with four major arguments for this association.

Sree Padma and Anthony Barber also associate the earlier development of the Tathāgatagarbha Sūtra with the Mahāsāṃghikas, and conclude that the Mahāsāṃghikas of the Āndhra region were responsible for the inception of the Tathāgatagarbha doctrine.

The Śrīmālā Sūtra says:

The Tathagatagarbha is not born, does not die, does not transfer [Tib: ’pho-ba], does not arise. It is beyond the sphere of the characteristics of the compounded; it is permanent, stable and changeless.

As the Śrīmālā Sūtra states:

The tathāgatagarbha is the sphere of experience of the Tathāgatas [Buddhas]

Anunatva Apurnatva Nirdeśa

The development of the Buddha-nature doctrine is closely related to that of Buddha-matrix (Sanskrit: tathāgatagarbha). In the Anunatva-Apurnatva-Nirdeśa, the Buddha links the tathāgatagarbha to the Dharmadhātu (ultimate, all-equal, uncreated essence of all phenomena) and to essential being, stating:

What I call "be-ing" (sattva) is just a different name for this permanent, stable, pure and unchanging refuge that is free from arising and cessation, the inconceivable pure Dharmadhatu.

Angulimaliya Sūtra

Every being has Buddha-nature (Buddha-dhatu). It is indicated in the Angulimaliya Sūtra that if the Buddhas themselves were to try to find any sentient being who lacked the Buddha-nature, they would fail. In fact, it is stated in this sutra that the Buddhas do discern the presence of the everlasting Buddha-nature in every being:

Even though all Buddhas themselves were to search assiduously, they would not find a tathāgata-garbha (Buddha-nature) that is not eternal, for the eternal dhātu, the buddha-dhātu (Buddha Principle, Buddha Nature), the dhātu adorned with infinite major and minor attributes, is present in all beings.

Belief and faith in the true reality of the tathāgatagarbha is presented by the relevant scriptures as a positive mental act and is strongly urged; indeed, rejection of the tathāgatagarbha is linked with highly adverse karmic consequences. In the Angulimaliya Sutra it is stated that teaching only non-self and dismissing the reality of the tathāgatagarbha karmically lead one into most unpleasant rebirths, whereas spreading the doctrine of the tathāgatagarbha will bring benefit both to oneself and to the world. We read:

Those who were donkeys in previous lives and paid no attention to the Tathâgata-garbha are now poor and eat coarse food as donkeys do. In future lives, too, apart from being poor, they will be born into lowly kshatriya [military] families. These are none other than the people who have no faith in the Tathâgata-garbha and cultivate the notion of no-Self, for they will be like prostitutes, outcastes, birds and donkeys [...] People who lack learning and have wrong views get angry with those who teach the Tathâgata-garbha to the world, and [those unlearned people] expound non-Self in place of the Self as their doctrine. He who teaches the Tathâgata-garbha, even at the expense of his own life, knowing that such people are inexperienced with words and lacking in balance, has true patience and teaches for the benefit of the world.

Ratnagotravibhāga

Of disputed authorship, the Ratnagotravibhāga (otherwise known as the Uttaratantra), is the only Indian attempt to create a coherent philosophical model based on the ideas found in the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras. The Ratnagotravibhāga especially draws on the Srimaladevisimhanada Sutra. Despite East Asian Buddhism's propensity for the concepts found in the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras, the Ratnagotravibhāga has played a relatively small role in East Asian Buddhism. This is due to the primacy of sutra study in East Asian Buddhism.

The Ratnagotravibhāga sees the Buddha-nature (tathāgatagarbha) as "suchness" or "thusness" - the abiding reality of all things - in a state of tarnished concealment within the being. The idea is that the ultimate consciousness of each being is spotless and pure, but surrounded by negative tendencies which are impure. Professor Paul Williams comments on how the impurity is actually not truly part of the Buddha-nature, but merely conceals the immanent true qualities of Buddha mind (i.e. the Buddha-nature) from manifesting openly:

The impurities that taint the mind and entail the state of unenlightenment (samsara) are completely adventitious ... On the other hand from the point of view of the mind's pure radiant intrinsic nature, because it is like this it is possessed of all the many qualities of a Buddha's mind. These do not need actually to be brought about but merely need to be allowed to shine forth. Because they are intrinsic to the very nature of consciousness itself they, and the very state of Buddhahood, will never cease.

Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra (ca. 200 CE)

The Buddha-nature is equated in the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra with the changeless and deathless true self of the Buddha.

This Buddha-nature is described in the Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra to be incorruptible, uncreated, and indestructible. It is eternal awakeness (bodhi) indwelling samsara, and thus opens up the immanent possibility of liberation from all suffering and impermanence.

It is a recurrent theme of the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra that the Buddha-nature is indestructible and forever untarnished. Professor Jeffrey Hopkins translates several passages from the sutra in which the Buddha speaks of this topic and defines the Buddha-nature as pure, eternal, truly real self:

... that which has permanence, bliss, Self, and thorough purity is called the "meaning of pure truth" [...] Permanent is the Self; the Self is thoroughly pure. The thoroughly pure is called "bliss". Permanent, blissful, Self, and thoroughly pure is the one-gone-thus [i.e. Buddha] [...] Self means the matrix-of-one-gone-thus [i.e. the tathagatagarbha/ Buddha-nature]. The existence of the buddha-nature in all sentient beings is the meaning of "Self" [...] The buddha-nature, by its own nature, cannot be made non-existent; it is not something that becomes non-existent. Just the inherent nature called "Self" is the secret matrix-of-one-gone-thus [i.e. tathagatagarbha / Buddha-nature]; in this way that secret matrix cannot be destroyed and made non-existent by anything.

It cannot even be seen clearly even by 10th-level (i.e. highest level) bodhisattvas - although they vaguely perceive its presence. Yet once it is fully "seen and known", on that morning the bodhisattva "attains the sovereign self" (aishvarya-atman) and Buddhahood is achieved.

The Nirvāṇa Sūtra, which presents itself as the final teachings of the Buddha on the tathāgatagarbha, makes clear that there are two kinds of self of which he speaks: one mundane and mutable, the other Buddhic and eternal. The first is denied as truly real, while the second is affirmed as the only true reality. In this same sutra the Buddha explains that he proclaims all beings to have Buddha-nature (which is used synonymously with "tathāgatagarbha" in this sutra) in the sense that they will in the future become Buddhas.:

Good son, there are three ways of having: first, to have in the future, Secondly, to have at present, and thirdly, to have in the past. All sentient beings will have in future ages the most perfect enlightenment, i.e., the Buddha nature. All sentient beings have at present bonds of defilements, and do not now possess the thirty-two marks and eighty noble characteristics of the Buddha. All sentient beings had in past ages deeds leading to the elimination of defilements and so can now perceive the Buddha nature as their future goal. For such reasons, I always proclaim that all sentient beings have the Buddha nature.

The eternal refuge of the Dharmadhātu or Buddha-dhātu is transcendentally empty of all that is conditioned, afflicted, defective, and productive of suffering. It is equated in the Nirvāṇa Sūtra with Buddhic Knowledge (jñāna). Such Knowledge perceives both non-self and the self, emptiness (śūnyatā) and non-emptiness, wherein "the Empty is the totality of samsara [birth-and-death] and the non-Empty is Great Nirvana."

The tathāgatagarbha is, according to the final sutric teaching of the Mahāyāna Nirvāṇa Sūtra, the hidden interior Buddhic self (ātman), untouched by all impurity and grasping ego. Because of its concealment, it is extremely difficult to perceive. Even the eye of insight (prajñā) is not adequate to the task of truly seeing this tathāgatagarbha (so the Nirvāṇa Sūtra). Only the "eye of a Buddha" can discern it fully and clearly. For unawakened beings, there remains the springboard of faith in the tathāgatagarbha's mystical and liberative reality.

Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra (3rd century CE)

The later Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra presents the tathāgatagarbha as being a teaching completely consistent with and identical to emptiness. It synthesizes tathāgatagarbha with the emptiness (śūnyatā) of the prajñāpāramitā sutras. Emptiness is the thought-transcending realm of non-duality and unconditionedness: complete freedom from all constriction and limitation.

The Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra describes the tathāgatagarbha as "by nature brightly shining and pure," and "originally pure," though "enveloped in the garments of the skandhas, dhātus and ayatanas and soiled with the dirt of attachment, hatred, delusion and false imagining." It is said to be "naturally pure," but it appears impure as it is stained by adventitious defilements. Thus the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra identifies the luminous mind of the canon with the tathāgatagarbha.

It also equates the tathāgatagarbha (and ālaya-vijñāna) with nirvana, though this is concerned with the actual attainment of nirvana as opposed to nirvana as a timeless phenomenon.

In the later Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra it is said that the tathāgatagarbha might be mistaken for a self, which it is not. In fact, the sutra states that it is identical to the teaching of no-self. Yet in the concluding Sagathakam portion of the text, the sutra does not deny the reality of the Self; in fact it castigates such denial of the 'pure Self'. According to Thomas Cleary, "The original scripture rigorously rejects nihilism and does not ultimately deny either self or world", and quotes the sutra:

Confused thinkers without guidance are in a cave of consciousness running hither and thither seeking to explain the self. The pure self has to be realized first hand; that is the matrix of realization [Tathagatagarbha], inaccessible to speculative thinkers.

Because of the use of expedient means (upāya) by metaphors (e.g., the hidden jewel) in the way that the tathāgatagarbha was taught in some sutras, two fundamentally mistaken notions arose: first that the tathāgatagarbha was a teaching different from and somehow more definitive than the teaching of emptiness (śūnyatā), and second that tathāgatagarbha was believed to be a substance of reality, a creator, or a substitute for the ego-substance or fundamental self (ātman) of the Brahmans.

Responding to these two mistaken notions, in Section XXVIII of the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, Mahāmati asks Buddha, "Is not this Tathagata-garbha taught by the Blessed One the same as the ego-substance taught by the philosophers?"

The Blessed One replied: No, Mahamati, my Tathagata-garbha is not the same as the ego taught by the philosophers; for what the Tathagatas teach is the Tathagata-garbha in the sense, Mahamati, that it is emptiness, reality-limit, Nirvana, being unborn, unqualified, and devoid of will-effort; the reason why the Tathagatas who are Arhats and Fully-Enlightened Ones, teach the doctrine pointing to the Tathagata-garbha is to make the ignorant cast aside their fear when they listen to the teaching of egolessness and to have them realise the state of non-discrimination and imagelessness. I also wish, Mahamati, that the Bodhisattva-Mahasattvas of the present and future would not attach themselves to the idea of an ego [imagining it to be a soul]. Mahamati, it is like a potter who manufactures various vessels out of a mass of clay of one sort by his own manual skill and labour combined with a rod, water, and thread, Mahamati, that the Tathagatas preach the egolessness of things which removes all the traces of discrimination by various skilful means issuing from their transcendental wisdom, that is, sometimes by the doctrine of the Tathagata-garbha, sometimes by that of egolessness, and, like a potter, by means of various terms, expressions, and synonyms. For this reason, Mahamati, the philosophers' doctrine of an ego-substance is not the same as the teaching of the Tathagata-garbha. Thus, Mahamati, the doctrine of the Tathagata-garbha is disclosed in order to awaken the philosophers from their clinging to the idea of the ego, so that those minds that have fallen into the views imagining the non-existent ego as real, and also into the notion that the triple emancipation is final, may rapidly be awakened to the state of supreme enlightenment. Accordingly, Mahamati, the Tathagatas who are Arhats and Fully-Enlightened Ones disclose the doctrine of the Tathagata-garbha which is thus not to be known as identical with the philosopher's notion of an ego-substance. Therefore. Mahamati, in order to abandon the misconception cherished by the philosophers, you must strive after the teaching of egolessness and the Tathagata-garbha.

The tathāgatagarbha doctrine later became linked (in syncretic form - e.g. in the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra) with doctrines of Citta-mātra ("just-the-mind") or Yogācāra. Yogācārins aimed to account for the possibility of the attainment of Buddhahood by ignorant sentient beings: the tathāgatagarbha is the indwelling awakening of bodhi in the very heart of samsara. There is also a tendency in the tathāgatagarbha sutras to support vegetarianism, as all persons and creatures are compassionately viewed as possessing one and the same essential nature - the Buddha-dhatu or Buddha-nature. (See: vegetarianism in Buddhism.)