Buddhist texts by Jeffrey Hays

by Jeffrey Hays

No single canon, or collection, of scripture is accepted by all Buddhist sects. Early texts were made primarily for monks. The Pali Tripitaka is among the oldest texts. Different regions produced their own canons. Buddhist words and names have two forms: one in Sanskrit and one in Pali.

A lot of Buddhist dogma is handled with stories and fables rather than metaphysical pondering. The earliest doctrines were laid out in relatively easy to understand parables and anecdotes. Scholars believe that many of the miracles, myths and legends attributed to Buddha were created after his death "to convey the lofty intellectual ideas of Buddhism in a more understandable format" to poor uneducated people. Buddha himself was not big on ideology or dogma. His teachings were practical ways for people to gain the same insights he found by delving into themselves.

Because many of the scriptures are elaborations of the Buddha’s original brief statements by his disciples the Pali Cannon is more of a collection of elaborations, explanations and expansions of Buddha’s First Utterance or Discourse. Over the centuries, Buddhists scholars have reshaped these texts as Christians have with the Bible. In The End of Suffering: The Buddha in the World , journalist Pankaj Mishra wrote that Buddha’s dialogues were often “long-winded and repetitious” with “little of the artistry so evident in Plato.”

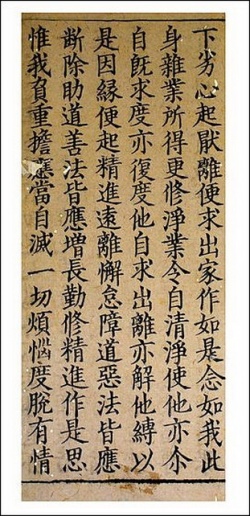

Writing, printing, reciting, chanting and reading Buddhist scriptures are thought of simple, easy ways for Buddhists to earn merit and create a better position for themselves in the afterlife. Many monks spend a good portion of their time printing Buddhist texts and hanging the paper on trees to dry. Often, the monks don't know what the prints say. Families sometimes place printed texts over their door of their homes keep thieves and demons away.

The 9th century Buddhist master Lin Chi said, “If you meet the Buddha on the road, kill him”—the point being that making a master teacher into an idol misses the essence of his teaching.”

Websites and Resources: Buddha Net buddhanet.net/e-learning/basic-guide ; Victoria and Albert Museum vam.ac.uk/collections/asia/asia_features/buddhism/index ; Religious Tolerance Page religioustolerance.org/buddhism ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Internet Sacred Texts Archive sacred-texts.com/bud/index ; Introduction to Buddhism webspace.ship.edu/cgboer/buddhaintro ;

Books: Buddhism by Christmas Humphrey (Pelican); Buddhism Explained by Phra Khantipalo; Buddhist Dictionary by Mahathera Nyanatiloka; Siddhartha by Herman Hesse. Also recommended are books by the Dalai Lama, Robert Thurman, a respected Buddhist scholar and former Tibetan Buddhist monk; and Thich Nhat Hanh, a Buddhist monk from Vietnam who has been involved with various anti-war activities. Film: Little Buddha

Websites and Resources on Buddhist Art: buddhism.org/board/main.cgi?board=BuddhistArt ; Buddhist Images buddhistimages.co.uk ; Religion Facts Images religionfacts.com/buddhism/gallery ; Buddhist Symbols viewonbuddhism.org/general_symbols_buddhism ; Buddhist Artwork buddhanet.net/budart/index ; Buddhism Images freewebs.com/buddhaimages ; Wikipedia article on Buddhist Art Wikipedia ; Buddha Images http://www.buddha-images.com/ ; Buddhist Art artlex.com/ArtLex/b/Buddhism ; Huntington Archives Buddhist Art kaladarshan.arts.ohio-state.edu ; Buddhist Art Resources academicinfo.net/buddhismart

Development of Buddhist Cannon

The Tipitaka Buddha appears to have written little or nothing himself. The earliest Buddhist writing that we have today date back to a period 150 years after Buddha's death. Early Buddhist literature consisted mostly of records of sermons and conversations involving The Buddha that were recorded in Sanskrit or the ancient Pali language.

According to tradition, the first texts were collected between the Council of Rajaharha, which took place after Buddha’s cremation, and the first Buddhist schism in the 4th century B.C. These texts consist primarily of orthodox doctrines and discourses and rules recited by the highly respected monks Ananda and Upali. They became the Vinaya Piataka and the Sutra Pitaka .

Concerns about different interpretations of Buddha’s teachings emerged early. The main goal of the council at Rajagaha was to recite out loud the Dharma (Buddha’s teachings) and the Vinaya (a code of conduct for monks) and come to some agreement on what were the true teachings and what should be preserved, studied and followed. Their guiding belief was that “Dharma is well taught by the Bhagavan (“the Blessed One”)” and that it is self-realized “immediately,” and is a “a come-and-see thing” and it leads “the doer of it to the complete destruction of anguish.”

The Vinaya-Pijtaka (the rules for monastic life) was developed at the First Council from a question and answer session between the Upali and the Elder Kassapa. The Sutra-Pijtaka (“Teaching Basket”) is a collection of teachings and sayings from Buddha, often called the sutras . It came about from the dialogue between young Anada an the Elder Kassapa about Dharma. A third basket, the Abhidhamma Pitaka (Metaphysical Basket) was also produced. It contains detailed descriptions of Buddhist doctrines and philosophy. Its origin is disputed. Together these made up the Tipitaki (Three Baskets of Wisdom), the foundation of Buddhism, and sometimes called the Pali Cannon because it was originally written in the ancient Pali language.

Theravada Buddhist Texts

Buddhist sacred scriptures consist of the Tipitaki (Three Baskets of Wisdom) and the Dhammapada . The Tipitaka is 2,500 years old, covers a period of two millennia and is sometimes called the Pali Cannon because it was originally written in the ancient Pali language. Forming the canon for the Theravada sect, it is 16,000 pages long and contains in 53 volumes. The texts that exist today have has mainly been compiled British scholars over the past century. One scholar who helped compile them told AFP, "After the whole 16,000 pages, you'd probably be too old to write down your conclusions.”

The first basket is the Vinaya Piataka (“Discipline Basket”). This text is made up of simple rules prescribed for people who wish to become devote Buddhists or monks. The Sutra Pitaka (“Teaching Basket”) is comprised of teachings and sayings of Buddha. The Abhidhamma Pitaka (“Metaphysical Basket”) has detailed descriptions of Buddhist doctrines and philosophy.

The Dhammapada is a collection of more sayings from Buddha. Other commentaries and Buddhist literary pieces are called sutras . Sayings attributed to The Buddha are also called sutras . The Jatakas is a group of stories that tell of Buddha's rebirths in the form of Bodhisattvas and animals, with each story embodying lesson from Buddha's teachings.

Mahayana Buddhist Texts

Most of the Mahayana canon is in the form of Sutras, Sastras and Tantras. Sutras are the most authoritative and widely accepted as doctrine. Sustras are much less universally accepted and are usually associated with a particular school. They are often commentaries attributed by name to a person with a specific school. Tantras are secret documents linked with the esoteric Tantric sects that are only supposed to be viewed by those who have been properly initiated.

Mahayana sutras are usually statements attributed to The Buddha centuries after he supposedly said them but are true enough to Buddhist doctrines that they have been accepted as truths. Sutras are often chanted in prayers and written or printed again and again to earn merit.

Most Mahayana literature is in Sanskrit, and some is in Chinese, Tibetan and Central Asian languages. The most widely used sutras are from The Perfection of Wisdom, of which there are about 30 different version put together over about a 700 year period.

Duahang Diamond sutra from China

The Lotus of the Good Law Sutra, or more simply the Lotus Sutra, is one of the most widely venerated and beautiful Buddhist scriptures. Followers often believe that salvation can be achieved by repeatedly chanting, "I take my refuge in the Lotus Sutra" and passages from the Lotus sutra in front of a small altar containing a scroll with Chinese characters representing the Lotus Sutra. Translations of it into English or other Western languages are not very good.

A 40-year-old Japanese housewife told Time she wakes up at dawn, places rice and water on the family altar and chants the same passages from the Lotus sutra over and over for around 25 minutes while kneeling and clasping her hands together around prayer beads. After she makes breakfast and gets her husband and children out the door she spends another 45 minutes chanting. "I feel so good afterwards," she said, refreshed and ready for the day."

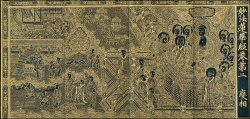

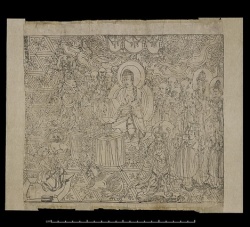

Wood Block Printing and the World’s Oldest Book

Buddhist monasteries were instrumental in the development of the world’s first block printing in China in the A.D. 7th century. Buddhists believe that a person can earn merit by duplicating images of Buddha and sacred Buddhist texts. The more images and texts one makes the more merit one earns. Small wooden stamps—the most primitive form of printing—as well as rubbings from stones, seals, and stencils were used to make images over and over. In this way printing developed because it was "the easiest, most efficient and most cost effective way" to earn merit.

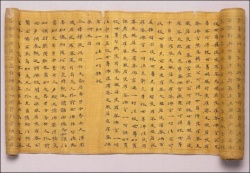

The world's oldest surviving book, the Diamond Sutra, was printed in China in A.D. 868. It consists of Buddhist scriptures printed on 2½-foot-long, one-foot-wide sheets of paper pasted together on one 16-foot-long scroll. Because virtually all original Indian scriptures have been lost Chinese translations of Indian scriptures have been invaluable in trying to figure out what the original Indian texts said.

Sutra of the great virtue of wisdom

Text Sources: World Religions edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Encyclopedia of the World Cultures edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); The Creators by Daniel Boorstin National Geographic articles. Also the New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.