Monks

Textualists and Workers

From the viewpoint of what we might call vocation, there were two types of monks at Sera:

monks who engaged in studies, called “textualists” (pechewa), and

those who engaged in the day-to-day work of the monastery, or more simply “workers.”21

By some estimates, less than 25 percent of all the monks living at Sera were textualists.

Textualists generally had a higher status than worker monks, both in the monastery and in the society at large.

They were perceived as engaging in the type of work for which a monk’s life was intended: study and prayer.

This does not mean that they were pampered or uncritically revered.

If a textualist got out of line – for example, if he took advantage of workers or became too full of himself – even an uneducated worker monk would be quick to put him in his place.22

Textualists tended to be poorer than worker monks because they spent their free time memorizing and studying, and were thus unable to engage in business or other forms of work to augment their income.

Within the category of textualist, monks were further distinguished according to the level they had reached in the curriculum.

Monks in the more advanced classes had greater privileges than those in the lower classes, and monks who had completed their studies and who had been awarded the geshé degree occupied one of the highest positions in the monastery, second only to lamas.

There were also different ranks of geshés – depending upon whether the degree had been granted internally by the college (rikram), by the monastery’s two philosophical colleges jointly (lingsep), or whether it had been granted by the Tibetan government in public examinations (tsokram and lharam).23

Of the monks who completed the geshé degree many would return to their home monastery to teach. Some would enter retreat.

If they had been awarded the higher geshé degree, they could enter one of the two Tantric Colleges (usually for a two-year period, at the end of which they could either return to Sera, go into retreat, or else return to their home monastery).

Some geshés would simply remain at Sera and teach after getting their degree.

Workers were of various types. Some worker monks spent their time in various ventures that supplied them with money for living expenses: for themselves and for the members of their household (shaktsen).

Others worked for wealthier monks – for example, in lamas’ households (labrang) – where they were provided for.

Some monks worked for the various administrative units of the monastery: for regional houses (khangtsen), colleges (dratsang) or for the Sera Lama Society (lachi).

Some worked outside the monastery. Monks engaged in a variety of work:

Kitchen work:

cooking

purchasing supplies

overseeing monk-cooks or hired kitchen staff

serving tea and food in assemblies

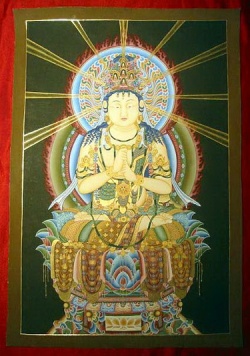

Serving as caretakers of temples or chapels:

making offerings on the altars

cleaning

receiving the offerings made by pilgrims and worshippers

serving as guards to ensure that nothing was stolen from altars

accounting for the goods and money received

selling religious goods (protection amulets, blessed pills, etc.)

Serving as part of the ritual staff in specific chapels:

meeting with prospective patrons who wanted to commission rituals, and providing them with a financial accounting after the fact

preparing for the ritual (buying the necessary offerings, making ritual cakes, etc.)

enacting the ritual

Working as servants or hired-help:

within the monastery (to lamas, senior teachers, wealthy monks, and administrators)

outside the monastery (in restaurants, on farms, and in other businesses)

As artisans, craftsmen, musicians or skilled laborers:

painting (tangka, statues, wall murals, etc.) (lhadripa)

building statues (lhazopa)

serving as musicians (rölyangpa)

printing texts

supervising construction projects

Engaging in business:

trading (both locally and in outlying districts)

banking (lending money for interest)

safeguarding the jewelry or other precious objects that were left as collateral by those who borrowed money

debt/loan collection

accounting

tending the estates (of wealthy lamas, and of the various administrative subunits of the monastery), either as workers or as overseers.

Many of these forms of work were looked down upon. They were seen as inappropriate for monks, and even before 1959 there were attempts to reform the monasteries, encouraging monks to give up things like money-lending.24 For the most part, however, these attempts at reform were not heeded. You can learn more about each of these forms of work under Activities.

Many workers were dopdops.

These were worker monks who organized themselves into fraternities. These fraternal units – or “parks” (lingka), as they were called – inducted members, did morning group physical workouts, met together for food and ritual, and sporadically convened inter-fraternity athletic competitions.

They wore their clothes in a special fashion, donned side-locks, walked with a swagger, and wore special keys on their belts that they used as weapons in fights. They also were known to have a fondness for boys.

Sometimes they kept younger monks from within the monastery as their lovers.

Occasionally they obtained boys (sometimes by force!) from the local Lhasa community for periods of time.25

The last abbot of the Jé College of Sera before 1959, Geshé Lhündrup Tapkhé, abolished the institution of the dopdop. To read an excerpt from the memoirs of a former Sera dopdop,

[21] Of course, there were also in the monastery a number of monks who did not study or engage in formal work. Some of these were senior monks who simply tended to the affairs of their household.

Others were engaged in intensive practice (e.g., retreat). Still others were what, in today’s parlance, we would call “slackers.”

Given that it was impossible to subsist on the offerings that monks received from their college and from other regular sources (e.g., from donors in assemblies, at the Great Prayer Festival (Mönlam Chenmo), etc.), slackers had to have outside sources of funding to survive at Sera.

[22] Assuming, of course, that the monks were more or less equals, e.g., in age. It would be unlikely that a very junior monk of any kind would challenge a senior monk. See the memoirs of Tashi Khedrup, a dopdop worker monk at Sera, on his run-in with some textualists:

[23] On the different types of geshé degrees, see the relevant section of the essay by Prof. Georges Dreyfus on the Sera Project Website; see also http://www.tibet.com/.

Both of these articles are based on the system in place at Drepung, where the terminology was somewhat different. Instead of Sera’s rikrampa, for example, Drepung used the term dorampa. It remains to be seen whether these two forms of the geshé degree are identical.

[24] See, for example, the decree directed at Sera by the Tsemönling regent in 1820. In Tshe dbang rin chen, ed., Se ra theg chen gling (Pe cin: Mi rigs dpe skrun khang, 1995), 122-24 and 168-71.

[25] See Melvyn C. Goldstein, “A Study of the Ldob Ldob," Central Asiatic Journal 9, no. 2 (1964): 125-41.