Pure Land Buddhism

Pure land Buddhism (simplified Chinese: 净土宗; traditional Chinese: 淨土宗; pinyin: Jìngtǔzōng; Japanese: 浄土仏教[1], Jōdo bukkyō; Korean: 정토종, jeongtojong; Vietnamese: Tịnh Độ Tông), also referred to as Amidism in English, is a broad branch of Mahāyāna Buddhism and currently one of the most popular traditions of Buddhism in East Asia. Pure land is a branch of Buddhism focused on Amitābha Buddha. The term is used to describe both the Pure land soteriology of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which may be better understood as Pure land traditions, and the separate Pure land sects that developed in Japan; in other countries and times, it formed part of the basis of Mahāyāna Buddhist traditions.

Pure land oriented practices and concepts are found within basic Mahāyāna Buddhist cosmology, and Form an important component of the Mahāyāna Buddhist traditions in China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Tibet. In Japan, however, Pure land Buddhism also became an independent school in its own right as can be seen in the Jōdo-shū and Jōdo Shinshū schools.

Early history

The Pure land teachings were first developed in India, and were very popular in Kashmir and [[Wikipedia:Central Asia|Central Asia]], where they may have originated. Pure land sutras were brought from the Gandhāra region to China as early as 147 CE, when the Kushan Monk Lokakṣema began translating the first Buddhist sūtras into Chinese. The earliest of these translations show evidence of having been translated from the Gāndhārī Language, a prakrit descended from Vedic Sanskrit, which was used in Northwest India.

The Pure land sūtras are principally the Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, Longer Sukhāvativyūha Sūtra, and the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra. The shorter Sūtra is also known as the Amitābha Sūtra, and the longer Sūtra is also known as the Infinite Life Sūtra. These sutras describe Amitābha and his Pure land of Bliss, called Sukhāvatī. Also related to the Pure land tradition is the Pratyutpannabuddha Saṃmukhāvasthita Samādhi Sūtra, which describes the practice of reciting the name of Amitābha Buddha as a Meditation method. In addition to these, many other Mahāyāna texts also feature Amitābha Buddha, and a total of 290 such works have been identified in the Taishō Tripiṭaka.

In the Longer Sukhāvativyūha Sūtra, The Buddha begins by describing to his attendant Ananda)] a past Life of The Buddha Amitābha. He states that in a past Life, Amitābha was once king who renounced his kingdom, and became a Bodhisattva Monk named Dharmākara ("Dharma Storehouse"). Under the guidance of The Buddha Lokeśvararāja ("World Sovereign King"), innumerable Buddha-lands throughout the ten directions were revealed to him. After meditating for five eons as a Bodhisattva, he then made a great series of vows to save all Sentient beings, and through his great Merit, created the realm of Sukhāvatī ("Ultimate Bliss"). This land of Sukhāvatī would later come to be known as the Pure land (Ch. 淨土) in Chinese translation.

In the Buddhist traditions of India, Pure land doctrines and practices were disseminated by well-known exponents of the Mahāyāna teachings, including Nāgārjuna and Vasubandhu. Although Amitābha is honored and venerated in Pure land traditions, this was clearly distinguished from worship of the Hindu gods, as Pure land practice has its roots in the Buddhist ideal of the Bodhisattva.

The Pure land teachings first became prominent in China with the founding of Donglin Temple at Mount Lu (Ch. 廬山) by Huiyuan (Ch. 慧遠) in 402 CE. As a young man, Huiyuan practiced Daoism, but felt the theories of immortality to be vague and unreliable, and unrepresentative of the ultimate Truth. Instead, he turned to Buddhism and became a Monk learning under Daoan (Ch. 道安). Later he founded a Monastery at the top of Mount Lu, and invited well-known literati to study and practice Buddhism there, where they formed the White Lotus Society (Ch. 白蓮社). They accepted the Shorter Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra and the Longer Sukhāvativyūha Sūtra as their standards among the Buddhist sūtras, and they advocated the practice of reciting the name of Amitābha Buddha in order to attain Rebirth in the western Pure land of Sukhāvatī. The Mount Lu is regarded as the among the most sacred religious sites of the Pure land Buddhist tradition, and the site of the first Pure land gathering.

The Pure land teachings and Meditation methods quickly spread throughout China and were systematized by a series of elite monastic thinkers, namely Tanluan, Daochuo, Shandao, and others. The main teaching of the Chinese Pure land tradition is based on focusing the Mind with Mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti) through recitation of the name of Amitābha Buddha, so as to attain Rebirth in his Pure land of Sukhāvatī.

At a later date, the Pure land teachings spread to Japan and slowly grew in prominence. Genshin (942-1017) caused Fujiwara no Michinaga (966-1028) to accept the Pure land teachings. Hōnen (1133–1212) established Pure land Buddhism as an independent sect in Japan, known as Jōdo Shu. Today Pure land is an important Form of Buddhism in Japan, China, Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam.

The Pure land

Contemporary Pure land traditions see Amitābha expounding the Dharma in his Buddha-field (Skt. Buddhakṣetra), or "Pure land" (Ch. 净土, jìngtǔ), a region Offering respite from karmic transmigration. Amitābha's Pure land of Sukhāvatī is described in the Longer Sukhāvativyūha Sūtra as a land of Beauty that surpasses all other realms. It is said to be inhabited by many gods, men, Flowers, fruits, and adorned with wish-granting trees where rare birds come to rest. In Pure Land traditions, entering the Pure Land is popularly perceived as equivalent to the attainment of enlightenment. Upon entry into the Pure Land, the practitioner is then instructed by Amitābha Buddha and numerous bodhisattvas until full and complete enlightenment is reached. This person then has the choice of returning at any time as a bodhisattva to any of the six realms of existence in order to help all sentient beings in saṃsāra, or to stay the whole duration, reach Buddhahood, and subsequently deliver beings to the shore of liberation.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism, there are many buddhas, and each buddha has a pure land. Amitābha's pure land of Sukhāvatī is understood to be in the western direction, whereas Akṣobhya's pure land of Abhirati is to the east. While recognized by the Japanese Shingon sect, Eastern Pure Land Buddhism is less popular than Western Pure Land Buddhism. Though there are other traditions devoted to various Pure Lands, Amitabha's is by far the most popular.

Meditation

Charles Luk identifies three meditation practices as being widely used in Pure Land Buddhism.

Mindfulness of Amitābha Buddha

Repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha is traditionally a form of Mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti). This term was translated into Chinese as nianfo, by which it is popularly known in English. The practice is described as calling the buddha to mind by repeating his name, to enable the practitioner to bring all his or her attention upon that buddha (See: samādhi). This may be done vocally or mentally, and with or without the use of Buddhist prayer beads. Those who practice this method often commit to a fixed set of repetitions per day, often from 50,000 to over 500,000. According to tradition, the second patriarch of the Pure Land school, Shandao, is said to have practiced this day and night without interruption, each time emitting light from his mouth. Therefore he was bestowed with the title "Great Master of Light" (大師光明) by the Tang Dynasty emperor Gao Zong (Ch. 高宗).

In Chinese Buddhism, there is a related practice called the "dual path of Chán and Pure Land cultivation", which is also called the "dual path of emptiness and existence." ] As taught by Nan Huaijin, the name of Amitābha Buddha is recited slowly, and the Mind is emptied out after each repetition. When idle thoughts arise, the phrase is repeated again to clear them. With Constant practice, the Mind is able to remain peacefully in Emptiness, culminating in the attainment of Samādhi.

Pure land Rebirth Dhāraṇī

Repeating the Pure land Rebirth Dhāraṇī is another method in Pure land Buddhism. Similar to the Mindfulness practice of repeating the name of Amitābha Buddha, this dhāraṇī is another method of Meditation and recitation in Pure land Buddhism. The repetition of this dhāraṇī is said to be very popular among traditional Chinese Buddhists. It is traditionally preserved in Sanskrit, and it is said that when a devotee succeeds in realizing singleness of Mind by repeating a Mantra, its true and profound meaning will be clearly revealed.

- namo amitābhāya tathāgatāya tadyathā

- amṛtabhave amṛtasaṃbhave

- amṛtavikrānte amṛtavikrāntagāmini

- gagana kīrtīchare svāhā

The Chinese use only the Chinese 生淨土咒 also known as this 往生淨土神咒 You can find this reprinted in various places like Hsi Lai Temple and City of 10,000 Buddhas www.cittbUSA.org Daily Recitation Book, The Daily Recitation Book is the standard. The translation exists in various forms and this is one is commonly used

Pure Land Rebirth Spell 往(wǎng) 生(shēng) 淨(jìng)土(tǔ) 神(shén) 咒(zhòu)

- I bow to Infinite branch! A Buddha!

- 南(nán)無(mó) 阿(ā)彌(mǐ)多(duō)婆(pó)也(yě)。哆(duo)他(tā)伽(qiē)多(duō)也(yě)。

- His virtue! Immortal being! Immortal,

- 哆(duo)地(dì)夜(yè)他(tā)。阿(ā)彌(mǐ)利(lì)都(dōu)婆(pó)毗(pí)。阿(ā)彌(mǐ)利(lì)哆(duo)。

- mind being! Immortal, origin delight!

- 悉(xī)耽(dān)婆(pó)毗(pí)。阿(ā)彌(mǐ)利(lì)哆(duo)。毗(pí)迦(jiā)蘭(lán)帝(dì)。

- Immortal, origin delighted! Desire!

- 阿(ā)彌(mǐ)利(lì)哆(duo)。毗(pí)迦(jiā)蘭(lán)多(duō)。伽(qiē)彌(mǐ)腻(nì)。

- Warrior praised! Verse maker, So it is!

- 伽(qiē)伽(qiē)那(nà)。枳(zhǐ)多(duō)迦(jiā)利(lì)。娑(suō)婆(pó)訶(hē)。

The late Ven. Master Lok To translated the Daily Recitation his last work of the The Buddhist Liturgy 佛會課誦 available for free in all Chinese Buddhist temples worldwide. This translation is with his permission in 2006. It is located on page 64 of Rise Up! Buddhist Study and Practice Guide Morning Service by Ven. Hong Yang Bhikshuni.

Visualization methods

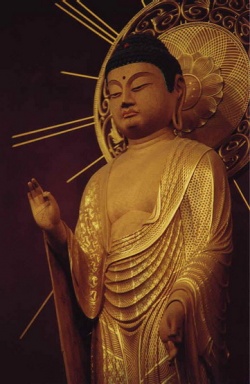

Another practice found in Pure Land Buddhism is meditative contemplation and visualization of Amitābha Buddha, his attendant bodhisattvas, and the Pure Land. The basis of this is found in the Amitāyurdhyāna Sūtra ("Amitābha Meditation Sūtra"), in which the Buddha describes to Queen Vaidehi the practices of thirteen progressive visualization methods, corresponding to the attainment of various levels of rebirth in the Pure Land. The first of these steps is contemplation of a setting sun, until the visualization is clear whether the eyes are open or closed. Each progressive step adds complexity to the visualization of Sukhāvatī, with the final contemplation being an expansive visual which includes the Amitābha Buddha and his attendant bodhisattvas. According to Inagaki Hisao, this progressive visualization method was widely followed in the past for the purpose of developing samādhi. Visualization practises for Amitābha are also popular in Japanese Shingon Buddhism as well as other schools of Esoteric Buddhism.

Going to the Pure Land

Practitioners claim there is evidence of dying people going to the pure land, such as:

- Knowing the time of death (預知時至): some prepare by bathing and reciting the name of the Buddha Amitabha.

- The "Three Saints of the West" (西方三聖): Amitābha Buddha and the two bodhisattvas, Avalokiteśvara on his right and Mahāsthāmaprāpta on his left, appear and welcome the dying person. Visions of other buddhas or bodhisattvas are disregarded as they may be bad spirits disguising themselves, attempting to stop the person from entering the Pure Land.

- Records of practicing Pure Land Buddhists who have died have been known to leave śarīrā, or relics, after cremation.

The last part of the body to become cold is the top of the head (posterior fontanelle). In Buddhist teaching, souls who enter the Pure Land leave the body through the fontanelle at the top of the skull. Hence, this part of the body stays warmer longer than the rest of the body. The Verses on the Structure of the Eight Consciousnesses (八識規矩補註), reads: "to birth in saints the last body temperature in top of head, to deva in eyes, to human in heart, to hungry ghosts in belly, to animals in knee cap, to the hells-realm in sole of feet." See also: phowa.

The dying person may demonstrate some, but not necessarily all, of these evidences. For example, his facial expression may be happy, but he may not demonstrate other signs, such as sharira and dreams.

Few buddhists also have practiced the harder Pratyutpanna samadhi.

The practice Fudaraku Tokai (補陀落渡海) in ancient Japan is viewed as religious suicide and is not practiced today.

Variance between traditions

Indian Buddhism

Regarding Pure Land practice in Indian Buddhism, Hajime Nakamura writes that as described in the Pure Land sūtras from India, Mindfulness of the Buddha (Skt. buddhānusmṛti) is the essential practice. These forms of mindfulness are essentially methods of meditating upon Amitābha Buddha.

Chinese Buddhism

In Chinese Buddhism, Pure Land practice never became a sect of Buddhism separate from general Mahāyāna practice. In particular, Pure Land and Zen practice are often seen as being mutually compatible, and no strong distinctions are made. Chinese Buddhists have traditionally viewed the practice of meditation and the practice of reciting Amitābha Buddha's name, as complementary and even analogous methods for achieving enlightenment.This is because they view recitation as a Meditation method used to concentrate the Mind and purify thoughts. Chinese Buddhists widely consider this Form of recitation as a very effective Form of Meditation practice.

Japanese Buddhism

In Japanese Buddhism, Pure land practice exists independently as four sects: Jōdo-shū, Jōdo Shinshū, Yūzū-Nembutsu-shū and Ji-shū. Strong institutional boundaries exist between sects which serve to clearly separate these Pure land schools from the Japanese Zen schools. One notable exception to this is found in the Ōbaku Zen school, which was founded in Japan during the 17th century by the Chinese Buddhist monk Yinyuan Longqi (J. Ingen Ryuki). The Ōbaku Zen school retains many Chinese features such as Mindfulness of Amitābha Buddha through recitation, and recitation of the Pure land sūtras.

Pure land concepts in Tibet

Tibetan Pure land Buddhism has a long and innovative history dating from the 8th-9th centuries CE, the times of the Tibetan Empire, with the translation and canonization of the Sanskrit Sukhāvatīvyūha sūtras in Tibetan. Tibetan compositions of pure-land prayers and artistic renditions of Sukhāvatī in [[Wikipedia:Central Asia|Central Asia]] date to that time. Tibetan pure-land literature forms a distinct genre (Tib. bde-smon) and encompasses a wide range of scriptures, "aspiration prayers to be born in Sukhāvatī", commentaries on the prayers and the sūtras, and meditations and rituals belonging to the Vajrayāna tradition. The incorporation of phowa (Mind transference techniques) in pure-land meditations is textually attested in the 14th century, in the The Standing Blade of Grass (Tib. 'Pho-ba 'Jag-tshug ma), a Terma text allegedly dating to the time of the Tibetan Empire. A good number of Buddhist treasure texts are dedicated to Buddha Amitābha and to rituals associated with his pure-land, while the wide acceptance of phowa in Tibetan Death rituals may owe its popularity to pure-land Buddhism promoted by all schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

The Terton Rigdzin Longsal Nyingpo (1625–1682/92 or 1685–1752) of Katok Monastery revealed a Terma on pureland. This Terma entailed phowa during the Bardo of dying, sending the Mindstream to a pureland.

Gyatrul (b.1924), in a purport to the work of Chagmé (Wylie: Karma-chags-med, fl. 17th century), rendered into English by Wallace (Chagmé et al., 1998: p. 35), states:

- It is important to apply our Knowledge internally. The Buddha attained Enlightenment in this way. The pure lands are internal; the Mental Afflictions are internal. The crucial factor is to recognize the Mental Afflictions. Only by recognizing their nature can we attain Buddhahood.

Pure land Buddhism, also sometimes referred to as Amidism, is a broad branch of Mahayana Buddhism and currently one of the most popular Schools of Buddhism in East Asia, along with Chán (Zen). In Chinese Buddhism, most Monks practise it in combination with Chán or other practices. It is a devotional or "Faith"-oriented branch of Buddhism focused on Amitābha Buddha. Pure land Buddhism is often found within Mahayana Buddhist practices such as the Chinese Tiantai school, or Japanese Shingon Buddhism. However, Pure land Buddhism is also an independent school as seen in the Japanese Jōdo Shū and Jōdo Shinshū schools. There is not one school of Pure land Buddhism per se; rather it is a large subset of the Mahayana branch of Buddhism. One key concept behind Pure land Buddhism is that Nirvana has become increasingly difficult to obtain through Meditative practices. Pure land Buddhism teaches that only through devotion to Amitābha Buddha and looking towards Amida Buddha for guidance can one be reborn in the Pure land, a perfect heavenly abode in which Enlightenment is guaranteed. Pure land Buddhism was popular among commoners and monastics as it provided a straightforward way of expressing Faith as a Buddhist. In medieval Japan it was also popular among those on the outskirts of society, such as prostitutes and social outcasts who, though often denied spiritual services in society, could find a Form of religious practice in the worship of Buddha Amitābha.

Overview

Pure land Buddhism is based on the Pure land sutras, first brought to China as early as 148 CE, when the Parthian Monk An Shigao began translating sutras into Chinese at the White Horse Temple in the imperial capital of Luòyáng, during the Hàn dynasty. The Kushan Monk Lokakśema, who arrived in Luòyáng two decades after An Shigao, is often attributed with the earliest translations of the core sutras of Pure land Buddhism. These sutras describe Amitābha and his Heaven-like Pure land, called Sukhāvatī.

Although Amitabha was mentioned or featured in a number of Buddhist sutras, the Larger Sutra of Immeasurable Life is often considered the most important and definitive. In this Sutra, The Buddha describes to his assistant, Ananda, how Amitabha, as an advanced Monk named Dharmakara, made a great series of vows to save all beings, and through his great Merit, created a realm called the Land of Bliss (Sukhavati). This paradise would later come to be known as the Pure land in Chinese translation. Pure land Buddhism played a small role in early Indian Buddhism, particularly the Mahayana branch, but first became prominent with the founding of a Monastery upon the top of Mount Lushan by Hui-yuan in 402. It quickly spread throughout China and was systematised by a series of elite monastic thinkers, namely Tanluan, Daochuo, Shandao, and others. The religious movement spread to Japan and slowly grew in prominence. Hōnen (1133–1212) established Pure land Buddhism as an independent sect in Japan, known as Jōdo Shu. Today Pure land is, together with Chan (Zen), the dominant Form of Buddhism in China, Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Contemporary Pure land traditions see Amitabha preaching the Dharma in his Buddha-field (Sanskrit: Buddhakṣetra), called the "Pure land" or "Western Pureland", a region Offering respite from karmic transmigration. The Vietnamese also use the term Tây Phương Cực lạc for "Western Land of Bliss", or more accurately, "Western Paradise". In such traditions, entering the Pure land is popularly perceived as equivalent to the attainment of Enlightenment. After practitioners attain Enlightenment in the Pure land, they have the choice of becoming a Buddha and entering Nirvana or returning to any of The Six Realms as bodhisattvas to help all living beings in Samsara. Thus, adherents believe that Amitabha Buddha provided an alternate practice towards attaining Enlightenment: the Pure land. In Pure land Buddhist Thought, Enlightenment is difficult to obtain without the assistance of Amitabha Buddha, since people are now living in a degenerate era, known as the Age of Dharma Decline. Instead of solitary Meditative work toward Enlightenment, Pure land Buddhism teaches that devotion to Amitabha leads one to the Pure land, where Enlightenment can be more easily attained. In medieval East Asian culture, this belief was particularly popular among peasants and individuals who were considered "impure", such as hunters, fishermen, those who tan hides, prostitutes and so on. Pure land Buddhism provided a way to practice Buddhism for those who were not capable of practicing other forms. In fact, in the Larger Sutra of Immeasurable Life the Amitabha Buddha makes 48 vows, and the 18th Vow states that Amitabha will grant Rebirth to his Pure land anyone who can recite his name as little as 10 times.

The Pure land

The Pure land is described in the Limitless Life Sutra as a land of Beauty that surpasses all other realms. More importantly for the Pure land practitioner, once one has been "born" into this land (birth occurs painlessly through Lotus Flowers), one will never again be reborn. In the Pure land one will be personally instructed by Amitabha Buddha and numerous Bodhisattvas until one reaches full and complete Enlightenment. In effect, being born into the Pure land is akin to achieving Enlightenment, through escaping Samsara, the Buddhist concept of "the Wheel of birth and Death."

Pure land Practice

Practitioners believe that Chanting Amitābha Buddha's name, or the nianfo, during their current Life allows them, at this Life's end, to be received with their Karma by Amitābha Buddha. The simplicity of this Form of veneration has contributed greatly to its popularity throughout East Asia. This practice is called Nembutsu in Japanese, or Buddha recitation, or "Being Mindful of The Buddha." An alternate practise found in Pure land Buddhism is Meditation or contemplation of Amitābha or his Pure land. The basis for this is found in the Contemplation Sutra, where The Buddha describes to Queen Vaidehi what Amitābha looks like and how to meditate upon him. Visualization practises for Amitābha are more popular among esoteric Buddhist sects, such as Japanese Shingon Buddhism, while the nianfo is more popular among lay followers. Some have claimed there is evidence of dying people going to the Pure land, such as: Knowing the time of Death - some prepare by bathing and Chanting the nianfo. The "three saints in the west" (Amitābha Buddha and the two bodhisattvas, Avalokiteśvara on his right and Mahāsthāmaprāpta on his left), appear and welcome the dying person. Visions of other Buddhas or bodhisttvas are disregarded as they may be bad spirits disguising themselves, attempting to stop the person from entering the Pure land. Leave sariras after Cremation. Relatives or friends may dream of the dying person. The last part of the Body to become cold is the top of the head (fontanel). In Buddhist teaching, souls who enter the Pure land leave the Body through the fontanel at the top of the skull. Hence, this part of the Body stays warmer longer than the rest of the Body. The Ba shi gui ju bu zhu, reads: "to birth in saints the last Body temperature in top of head, to Deva in eyes, to human in Heart, to hungry ghosts in belly, to Animals in knee cap, to the hells-realm in sole of feet." The dying person may demonstrate some, but not necessarily all, of these evidences. For example, their facial expression may be happy, but they may not demonstrate other signs, such as Sarira and Dreams.

Eastern Pure land

In esoteric Vajrayāna Buddhism, Amitābha's Western Pure land (Sukhāvatī) is the counterpart to Akṣobhya's Eastern Pure land, or Abhirati. While especially recognized by the Japanese Shingon sect, Eastern Pure land Buddhism is less popular than Western Pure land Buddhism.