Oral transmission

Oral transmission (Tib. ལུང་, lung; Wyl. lung; Skt. āgama) —

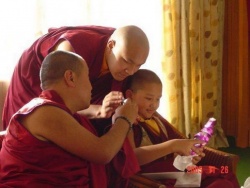

The verbal transmission of a teaching, meditation practice or mantra from guru to disciple, the guru having received the transmission in an unbroken lineage from the original source.

It is important to receive an oral transmission (sometimes called 'aural transmission' or 'reading transmission') from a teacher, in order to create an auspicious connection with a particular text or practice.

In the case of tantric texts, such as sadhanas or commentaries, this transmission occurs once one has received the relevant empowerment.

The reading transmission is passed down from master to student when the student listens to the teacher reading a text for which he holds a transmission, ultimately going back to the author of the text.

In this way, the student receives the blessing of the lineage without which he or she will not be able to understand the text fully in all its depth.

Some teachers even consider it inappropriate to read a Dharma text for which one has not yet received a transmission.

Internal Links

When people hear that the Buddhist scriptures were orally transmitted for several centuries, they assume that they must be very unreliable.

It is often said that the Tipiṭaka was first committed to writing in Sri Lanka in about 100 BCE, but this is a misunderstanding.

The source of this information is the ancient Sri Lankan chronicle, the Dīpavaṃsa.

But all this work says is that the Tipiṭaka was first written in Sri Lanka at that time. It may well have been written down much earlier in India, and indeed there is good reason to believe it was.

It is likely that this was done during the reign of King Aśoka.

This king was a devoted Buddhist, he was very concerned that the Dhamma should be preserved and disseminated, and he made wide use of writing as a part of public policy.

Everything we know about Aśoka suggests that committing the Tipiṭaka to writing would be the very thing he would have done.

If this is correct, it would mean that about 200 years passed between the writing of the Tipiṭaka and the Buddha’s passing.

However, the Mañjusrimūlakalpa says the Tipiṭaka was written down during the reign of Udāyibhadda, the son of King Ajātasattu (tadetat pravacanaṃ śastu likhāpayiṣyati vistaram).

If this is correct, it would mean that the Tipiṭaka was first written only about 30 years after the Buddha, when people who had actually met him were still alive.

Centuries before the Buddha, the brahmans, the hereditary priests of Brahmanism, had perfected ways of committing the Vedas to memory so they could be passed on to the next generation (itihāsa).

The earliest Vedas,the Ṛg Veda,date from between about 2000 and 1500 BCE and did not start being written until at least the 11th or 12th century CE.

This means that they were orally transmitted for years nearly 3000 years. Despite this, linguists and Indologists agree that the Vedas reflect daily life, beliefs and language of the time they were composed, i.e. that they have been faithfully handed down. How was this done?

A brahman’s whole life was dedicated to becoming a living receptacle for the Vedas.

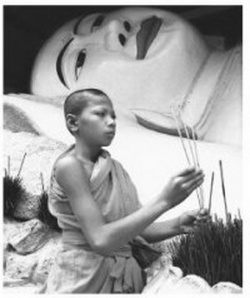

From an early age, he chanted them until he had committed them to memory and great attention was given to getting pronunciation, the intonation and the word order correct.

Usually a father was the ‘passer on’ of the sacred hymns and his son was the ‘receiver’ of them (D.I,89).

Many of the Buddha’s disciples were brahmans and they brought to their new faith the mnemonic skills they had been educated in.

These same skills were used to preserve the Buddha’s sermons, talks and sayings.

And like the Vedas, the suttas are clearly structured to be chanted.

They are full of mnemonic devices – rhyming verses, repetitions, numbered lists, stereotyped phrases, etc.

Even before the Buddha’s passing, monks and nuns would regularly chant the suttas in congregation (D.III,211).

The Buddha gave advice on how this should be done.

‘If one of your fellow monk quotes the Dhamma in the assembly, and if you think he has got the meaning and the word order wrong, or the first right but the second wrong, or vice versa, you should neither accept it nor reject it.

Rather, you should explain to him the correct meaning and the correct word order. But if one of your fellow monks quotes the Dhamma in the assembly, and if he gets both the meaning and the word order right, you should praise and applaud him and say, “Excellent!

How blessed and fortunate we are to have you as a friend and companion in the spiritual life who is so well-versed in both the pronunciation and the word order.”’ (condensed, D.III,128-9).

This made it difficult to add, delete or change anything in a sutta once it had been settled and committed to memory.

It is also important to realize that lay Buddhists had a role to play in orally transmitting the suttas too.

The Buddha said he wanted not just his ordained disciples but also his lay men and women disciples to be ‘knowers of the Dhamma’ so that they could ‘pass on’ what they had learned to others (D.II,105).

The Vinaya says that if a monk hears about a lay person who is dying and who knows a sutta that he doesn’t, the monk should go and learn it before the lay person passes away (Vin.I,140-1).

Inscriptions from Sanchi mention lay men and women who knew (i.e. by heart) suttas and sometimes whole collections of suttas.

The Divyāvadāna mentions some traveling merchants getting up before dawn to chant the Udāna, the Theragāthā and selections from the Sutta Nipāta ‘in their entirety.’

Whether they chanted these texts as they read them from a book or whether they did it from memory, we do not know. The tradition of committing the Buddhist scriptures to memory has not entirely died out.

There are still a few monks in Burma who can chant from memory the whole of the Tipiṭaka. See Poetry.

Style and Function, Mark Allan, 1997.