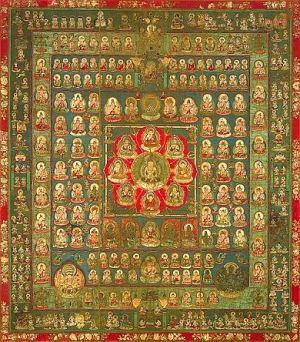

The Eight-Consciousnesses Model

Ben Connelly

his transformation has three aspects:

The ripening of karma, the consciousness of a self, and the imagery of sense objects.

This verse introduces us to the main subject of the first fifteen verses of this work: the Yogacara model for understanding consciousness. The purpose of this model is to help us see how we can let go of tendencies that lead to afflictive, painful, and difficult emotions and cultivate the capacity to manifest beneficial ones: emotions that are both more pleasant to experience and conducive to kindness toward others. This verse begins to explain the eight-consciousnesses model, a Yogacara innovation that is an expansion of Early Buddhism's teaching of the six consciousnesses, sometimes called the All.

In the earliest Buddhist teachings, Buddha says that to be free from suffering it's necessary to understand the All, which is comprised of these six consciousnesses: sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and thought. This All is the totality of our momentary conscious experience. We are instructed to direct our attention toward and directly know these six consciousnesses. The point is not that we develop some theory or ideas about them; rather, we should know them intimately; in a way that is much deeper than words can describe and that is suffused with compassion. In Buddhist practice we come to know things through mindfulness, through nonjudgmental, moment-to-moment awareness. As we pay attention to sight, sound, smell, taste, touch, and thoughts, we begin to see that they are just things that come and go. We begin to dis-identify with them, to not hold tightly but let them be. The realization that our thoughts are just something that is coming and going, that they are not ourselves, is often one of the most striking and liberating aspects people experience when they begin meditation.

This All is what this verse describes as "the imagery of sense objects." When Vasubandhu says that there are three aspects of the transformation of conscious ness, these six together make up the third of these transformations.

We call them transformations because they are just coming and going; they are simply a process of endless change. And imagery literally means the language used in literature to paint a vivid sensory picture in order to elicit emotion. This is a somewhat free translation of the Sanskrit term vijnapti, which is key to the last half of the "Thirty Verses" and will be discussed in detail later in the book. The purpose of its use here is to point out that what we take to be reality; the basic data of our sense experience, is actually in large part a creation of the habits of our consciousness, or we might say a manifestation of our unconscious narratives, and is intimately connected to the way we experience emotions.

So, this third transformation, the imagery of sense objects, is a process we know as experience: the All is readily apparent to us. Right now you can see this text, you are experiencing thought and sensations in the body, as a result of the six consciousnesses.

The first transformation, described in this verse as "the ripening of karma," and the second, "the consciousness of a self," are referred to in Sanskrit as alaya vijnana, or store consciousness, and manas, respectively These are the two elements that Yogacara added to its model of consciousnesses: your past conditioning and your sense that there is a "you" that is experiencing things.

The store consciousness is a way to describe the process by which karma ripens. The conditioning of our past is depicted as karmic seeds and the way those manifest in our present-moment experience as karmic fruit. Have you ever been standing in the rain and seen one person shuffling along scowling at the clouds and another smiling and bouncing along in the down pour? The emotional reactions and conduct of the two people is the result of their karmic conditioning. Karma doesn't make rain; it makes smiles and frowns, it makes hugs and fists.

The manas consciousness creates the sense that there is a self that experiences objects. In meditation as the storytelling mind relaxes and we settle into the com ing and going of phenomena-the crying of gulls, the occasional sighs of the meditator next to us, the worry ing about how soon the bell will ring-we often notice that there is a persistent aspect of mind that is a sense of experiencing things. In the Early Buddhist teachings, one meditation adept called this "the residual conceit: 'I am."' Katagiri Roshi called it "the observer" and said that this is one of the hardest things to let go of in meditation. This is manas, the sense that there is an I experiencing things.

Here we set the stage for our investigation of consciousness, so that we can be intimate with it, so that we may understand how to help it be well. The first half of the "Thirty Verses" will deal with the store consciousness, manas, and the six senses. We will see how by mindfulness of what appears in or as the six senses, we can experience and let go of the seeds of suffering in the storehouse, and plant and cultivate beneficial seeds. In so doing, we can participate in this transformation of consciousness, rather than being unconsciously swept along with it. We can offer our effort to allowing this process to be one that is conducive to well-being. We can see that the beneficial states of mind are ones where we are kind and compassionate toward what ever or whoever is here in the present moment. We can see how that softens and erodes our sense that we are self, separate from anything else. We can realize the Buddhist promise of our ability to joyfully disappear into the pure harmonious dynamic activity of the moment-consciousness only.

Source