The red-faced men III: The red-faced women

Sometimes it’s good to be wrong. It can make the questions you were asking more interesting. In the last two posts I’ve been discussing the characterization of the early Tibetans as ‘the red-faced men’. Although the Tibetan term itself (gdong dmar can) does not specify a gender, I have been using the masculine noun. My reasoning was that the term as we find it in the original Khotanese texts derived from encounters with the Tibetan army, so I came to the conclusion that the red face decoration was applied primarily by soldiers going into battle. So much for ‘the red-faced men’.

In fact, recent archaeological evidence that I have only just now become aware of (thanks to Kazushi Iwao) clearly shows that red face decoration was worn in civilian life, and by women as well as men. In 2002, the archeaologist Xu Xinguo excavated tombs in Guolimu, a village near Delingha in Qinghai Provice (Amdo), and discovered two beautifully painted coffin boards. The wooden boards, which are believed to date from the time of the Tibetan Empire, were painted with numerous scenes from everyday life, including hunting, oath-taking and funeral rites. Many of the people featured in the painting, both men and women, have faces decorated with red.

The people depicted here are probably the Azha, who were brought into the Tibetan Empire in the 7th century. But this red face painting was not just an Azha tradition; we know that it was practised in the Tibetan court itself. The Chinese Tang Annals say that Princess Wencheng, who came to marry the Tibetan King Songtsen Gampo in the 7th century, introduced various new customs to the Tibetan court (which is portrayed by the Chinese historians, not entirely fairly, as quite uncivilized). One of her innovations was to stop the Tibetans from painting their faces red.

As the princess disliked their custom of painting their faces red, Songtsen ordered his people to put a stop to the practice, and it was no longer done. He also discarded his felt and skins, put on brocade and silk, and gradually copied Chinese civilization.

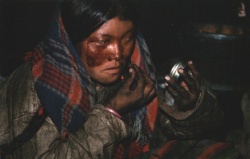

It may well be that the practice originated in the nomadic tribes of the northeast and western Tibet, and was later adapted by the Central Tibetans. Amazingly, even today a similar custom of red face painting is practised by the nomads of western Tibet. Here it is only the women who paint their faces, using a preparation made from boiled whey. The pictures here were taken by Melvyn Goldstein and Cynthia Beall, who lived with the nomads of the Changtang region for over a year from 1986-88. Goldstein and Beall observed that while nomads said that the red face makeup was used to protect the skin from sunburn, it was only used by younger women and particularly when they wanted to look good. Thus it was primarily decorative. The patterns of decoration used by these women are strikingly similar to those depicted on the ancient coffin covers.

So it seems that the practice of red face painting (by men and women) might have originated in Tibet’s northeast and west, and then been adopted by the early Tibetans, who later abandoned it during or after the Imperial period. Some of the western nomads, however, preserved the custom, although only among women.

And so it is simply incorrect to translate the Tibetan term gdong dmar can as ‘the red-faced men’. I should, and from now on will, use ‘the red-faced people’ or ‘the red-faced ones’. Being wrong can indeed be very interesting!

References

1. Bushell, S.W. 1880. “The Early History of Tibet: From Chinese Sources”. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 1880: 435-535. [p.445]

2. China Heritage Project. 2005. “New Discoveries in Qinghai”. China Heritage Newsletter 1 (online journal).

3. Goldstein, Melvyn and Cynthia Beall. 1990. Nomads of Western Tibet: The Survival of a Way of Life. London: Serindia Publications.

4. Luo Shiping. 2006. “A Research about the Drawing on the Coffin Board of Tubo located at Guolimu, Haixi, Qinghai Province”. Wenwu 2006.7: 68-82.

5. Yong-xian Li. 2006. “Rediscussion on the Bod-Tibetan Zhemian Custom”. Bulletin of the Department of Ethnology 25: 21-39.