The Pain of Attachment

by Corrado Pensa

There are various ways of expressing the combination of light and warmth. There is a flame, and this flame means both light and warmth at the same time. Now, if this is the culmination of the path—this light and warmth—it has to have been there right from the beginning, at least in a potential form. This is why I tend to emphasise `affectionate’ awareness, `affectionate’ mindfulness, `accepting’ awareness, `accepting’ mindfulness. I think we shall spare ourselves a little suffering if we start right away to cultivate this gentleness in combination with the thing itself, and more and more we realise that they are not two separate things.

When we say `nonjudgemental’ awareness, `nonjudgemental’ mindfulness, we are talking about `accepting’ mindfulness. We can also say, I believe, that when we understand acceptance, truly understand it, at that point we truly understand awareness, and vice versa—once we really understand awareness, we understand and realise true acceptance. Acceptance is an intrinsic path to mindfulness, to awareness; as with wisdom and compassion—they are two sides of the same coin. So the big picture comprises wisdom and compassion; the small, initial picture has a little mindfulness which, to some extent, is accepting. It goes from there, but I think it has to be correct from the beginning.

There can be a lot of misunderstanding about this word `acceptance’. What does it mean, for example, to accept a dishonest person? What it means, I think, is that we develop some compassionate respect for the suffering and confusion which is behind that person’s dishonesty, or as much as we can—it does take a lot of mindfulness and understanding—while at the same time actively opposing the dishonest ways of the person. In other words, the acceptance has to do with quiet courage and right action; otherwise it’s not acceptance, it’s passivity, fear, etc. This is a frequent misunderstanding. What then happens is that, underneath, people get angrier and angrier at the practice because they are forcing themselves into passive situations, or they don’t like the practice because they don’t like the idea of being passive. But this is a misunderstanding! `Right action’ is much more `right action’ if it comes from a place of nonreactivity, of acceptance. There should, however, be right action, otherwise it’s called paralysis; it’s called helplessness; it isn’t acceptance.

Suppose we have an appointment, maybe with a doctor or a lawyer, and when we arrive we find more people waiting than we expected—three, four times as many. Perhaps we accept the situation—we are mature practitioners and we accept the situation as it is. The other extreme, in case we are not mature practitioners, is that we spend the whole waiting time actively cultivating frustration and disappointment—that’s nonacceptance. The cultivation of nonacceptance is an activity we know very well, or maybe we don’t know it, but we do a lot of it.

If we think of it, nonacceptance is a very good opportunity for practise because it is made of attachment, aversion and ignorance. The three major intoxicants are there, and they are the basic ingredients of nonacceptance. So this is a good opportunity to apply our practice in a very fruitful way. And yet it’s not easy; it’s not simple at all! Why? Because of attachment—attachment to habits and especially to a few deeply ingrained habits. I am thinking of the habit of immediately fuelling attachment as soon as it arises, and the habit of immediately feeding aversion as it arises. Attachment arises and we jump in to feed it; aversion arises and we do the same. `Ignorance’ sees that these habits can thrive undisturbed. `Ignorance’ is the protective mother. Now, mindfulness, awareness, is a disturbance, and this is why we have to deal with so much resistance in our practice and life, because mindfulness is the major disturbance with regard to this habit. I want to quote from Joko Beck; this comes from Tricycle magazine:

The truth is we don’t want to observe, particularly if we are upset. What do we want to do? We want to be upset because then I remain the centre of the drama. If I observe, I weaken that self-centred position.

So we resist, inevitably. We should understand—and the practice is the best way—that the intoxicants [attachment, aversion and ignorance] are very well trained. You know, there is a lifetime’s practise behind the intoxicants; they are incredibly well kept, lubricated, oiled; they are sparkling. Every time aversion arises we are right there, fanning it, denying it, or acting it out—three different trainings. And sometimes we rotate the three trainings to keep supple. This is no exaggeration. The same with attachment. We think that one day we’ll get around to working on attachment and aversion, but at this time our life is asking something else of us. We might call ignorance the mother of all conflicts. Attachment and aversion are so powerful, so well trained, and yet we are capable of saying, `I’ve been practising for two years and I still have this and that.’ This also shows that ignorance can severely impair our sense of humour. With the intoxicants we’ve had a lifetime’s training, and with awareness we’ve had two years, and we’re complaining that very little has happened after those two years.

Dartmouth Castle, DevonWe therefore need what in this tradition is called citta-bhavana which is usually translated as `cultivation of mind’, and is another name for dharma-practice. Bhavana is a very good word because it comes from the root which means `being’, so bhavana is `coming into being’, the coming into being of the potential of our mind. We need this process of mind-purification in order to deal with the incredible power of the intoxicants. The Buddha said, `I don’t know of anything so intractable and so unreliable as a mind which has not been cultivated.’ Why is it so intractable and unreliable? Because all the power is in the hands of the intoxicants, because the mind is completely overpowered by the intoxicants. The Buddha in the same scripture said, `And I also don’t know of anything so reliable as a mind which has been cultivated, which has been purified.’

Mind-purification is a long, complex, enterprise. We can touch and see many parts of it, but part of it is elusive; it happens under water, so to speak. In this complex, exciting, difficult process, there should be what psychology calls `high tolerance for frustration’, `high tolerance for open-ended situations’. There is sometimes a lot of confusion about this because, no matter how much we know, we end up equating practise with concentration: `My practice, as good practice, equals good concentration; my bad practice equals bad concentration.’ So this is very tricky, very confusing. It means that when our practice becomes dry and difficult, we think it’s a failure. Practice which becomes difficult, however, or becomes dry, is intrinsic to mind-purification; it’s organic in a process of mind-purification. If these things never happen, either we are buddhas or something is off. We should also realise that a good laboratory in which to work on the contemplation of nonacceptance—which means working on the three intoxicants of attachment, aversion, and ignorance—is lack of self-acceptance; something which is very close at hand. There is plenty of opportunity for practice here.

Self-acceptance is the root of acceptance. Sometimes there can be a very generous spirit of service but with some naiveté in it because we do not realise that this very idealistic spirit is undermined by our lack of self-acceptance. So that has to be dealt with in our practise as a first priority. Self-realisation—I mean spiritual realisation itself—is very much linked with self-acceptance. I would like to read you a quote from a newspaper about Zen Master Aitken Roshi. He was diagnosed as having Hodgkin’s disease. This is a form of cancer which responds well to treatment. Aitken Roshi was being interviewed and he said, `I think everybody should do zazen all their lives and then have chemotherapy. The realisations I experienced years ago, following glimmers of understanding, were in effect within a personal container that rested on a stratum of deep self-doubt. The shock of massive dosages of chemotherapy drugs has been to break up the stratum. All my doubts have dropped away. At eighty years of age, I am at last liberated from the resistance I have long felt to other people and to the outside world generally. Now every day is a jewel, every jewel is different, every act, every thought, every encounter, is new and precious. I read the words of the old masters and laugh and laugh. What hilariously funny fellows they were. I remember the words and the kindness of all my teachers and weep with gratitude. I listen to the music of Bach and Mozart and Haydn, and thrill to the gorgeous sound. The thrush sings in the early morning in my heart.’

The basic ingredients of nonacceptance are the intoxicants. Let’s go back to aversion to the extent that we bring mindfulness, gentle mindfulness, to it. Realise its painful quality. Realise that aversion is like a cutting blade which creates suffering—first of all to ourselves, and then all around us. So what happens in our practice? More and more we catch ourselves about to feed aversion, about to fan the flames of aversion, and more and more we don’t like what we see. Our relationship to aversion changes. Aversion is still there but out relationship to it changes. It is not only because we’ve seen in a much clearer way its painful character—the suffering that it creates—but because we’ve seen the conditionality of it; it takes certain conditions for aversion to arise. When those conditions are not there, neither is aversion.

The frequent and repeated seeing of this conditioned quality of aversion tends to change our relationship, not only to the aversion, but also to many other things. This is especially important given the role that aversion has in our suffering. We also see that mental proliferation has a solidifying effect on it; it makes aversion into something much more solid. But the more we contemplate proliferation, the less powerful it is. This change of relationship has a specific word in Pali, nibbida, which means `getting happily tired of something we’ve been doing to ourselves’ for years, decades, desperately and ignorantly, and not only to ourselves. Another way of translating nibbida is `serene disenchantment’, with the emphasis being on `serene’. It’s a situation in which we’re not drawn any more to fanning the flames, to fuelling the aversion. Whenever we catch ourselves about to do these things, we tend to drop it more and more.

We fall sometimes, in old habits; we slide back; we regress and start yelling or nourishing self-aversion, but if we keep practising, we wake up again and find that we don’t really want to continue with those old habits. It’s an organic process. Sometimes people at the beginning of their practice have the idea that they are supposed to cut away aversion, but it isn’t a question of cutting, it’s a matter of weakening habits, of weakening one’s strongest addictions. We become disenchanted, and we become happy.

Yarrow By StreamNibbida is also linked to samvega, the urgency to practise. On the one hand we feel this disenchantment, and on the other we feel a stronger motivation to practise, an urgency to practise, and more joy in the practice, but this isn’t an anxious urgency.

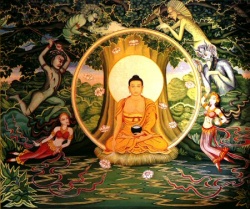

How do we work skilfully with attachment? Our tendency is to focus so strongly on the object of our attachment that we disregard the feeling of attachment itself. The bright lights are so distracting, so entrancing, that we get drawn in without noticing the tone of the attachment that we are experiencing. When we directly experience the feeling of attachment, we stop being so infatuated with the object, and break the trance. This is because we’ve got in touch with the contraction, with the movement of attachment itself, which is suffering. When we can feel the pain of attachment in its naked form, we stop allowing it to rule our lives and diminish our capacity for enjoyment and connection; we equate attachment with enjoyment; that’s wrong. We haven’t seen the truth of it.

Observing attachment with mindfulness gives us tremendous courage—we not only enjoy the times we get what we want, but also we’re not swept away by disappointment when we don’t. Mindfulness gives us immense spaciousness of mind. We can relax from our habit of clinging, of rarefying experience, of contracting our minds around what we want; it also gives us the ability to feel compassion, and we see the pain that we and others are led into over and over again by the hindrance of attachment. Finally, we find that we do not have to hold onto something or always get what we want in order to be happy. We realise that courage, spaciousness of mind, and compassion are themselves the ingredients of lasting happiness, of greater happiness. I would add that more and more we enjoy wise perception. In a sense, the joy of wise perception replaces the dubious joy of aversion or attachment, or the so-called joy of feeding attachment and aversion.

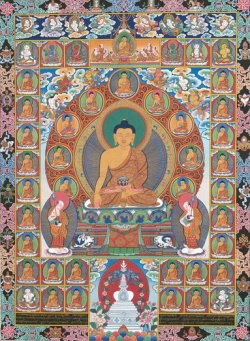

When this thing starts happening in our practice, we have a hard time believing it, `Is this true? I see that I’m doing wrong, I’m becoming tired of it, and I’m ceasing to do it. Is this really happening?’ Yes, it’s happening! This marvellous thing is the practice that’s been handed down for centuries and been experimented on generation after generation, experimented on and refined. That’s why sometimes practitioners happen to feel gratitude for the tradition. This doesn’t have anything to do with identifying with a tradition; it’s gratitude for this set of tools which has been handed down over the centuries. So, contemplation of nonacceptance seems to be a very direct road for working on our hindrances and developing true acceptance. The straight way to develop acceptance is the contemplation of nonacceptance. The straight way to develop patience is the contemplation of impatience. Other ways, other roads, are not direct and not as deep as the straight one.

In traditional terms, authentic acceptance is also called equanimity. If we consider the Buddha, I think we have an archetype of equanimity. To quote from The Middle Length Sayings No 137: `Here, monks, compassionate and seeking their welfare, the Buddha teaches the dhamma [truth]to the disciples out of compassion, saying: “This is for your welfare, this is for your happiness.”‘ Now, a few responses to his teaching are being considered in this sutta. The first one is a negative response from the disciples. `His disciples do not want to hear or exert their minds to understand. They turn aside from the teacher’s dispensation. With that, the Buddha is not satisfied and feels no satisfaction, yet he dwells unmoved, mindful and fully aware.’ Now, the Pali word which is translated `unmoved’ means `completely without intoxicants’. So he’s dissatisfied and doesn’t have an inch of aversion—dissatisfied without any aversion or attachment.

Cambodia. Photo © Janet NovakI think we should make a little effort to conceive this quality—`serenely dissatisfied’; that’s what it’s talking about. And then let’s consider the opposite situation—teaching dhamma to disciples out of compassion. In this case his disciples hear, accept, and exert their minds to understand. They do not turn aside from the teacher’s dispensation. With that, the Tathagata [the Buddha] is satisfied and feels satisfaction, yet he dwells unmoved, mindful, and fully aware.’ He is satisfied and is not attached to his satisfaction, which means he is totally free.

In another very interesting sutta of The Middle Length Sayings, No 47, the Buddha talks about how to recognise a Tathagata, a Buddha, and various ways are given for doing so, and then the sutta says that if a Buddha is a real Buddha, he will stick to the vinaya, the code of discipline, the rules of discipline—not because of fear, but simply because he has overcome attachment. And then, talking to his disciples, he says that if someone tells you that this is the case, what proof would you have that this is so? The Buddha then himself says, `This venerable one, whether dwelling in the sangha [community of monks] or dwelling alone, whether those near him are well behaved, whether they are ill behaved, whether they are concerned about material things, whether they are unsullied by material things—that venerable one does not despise anyone because of that.’ This is the proof—that he’s sticking to the vinaya—not out of fear, but because he has gone beyond attachment. If he has really gone beyond attachment, his heart is in a state of complete equanimity and he accepts everyone and everything.

If we put our body into a serious detoxification process, all the functions of our body fall into place, everything functions at its best; there is a complete balance from this detoxification. It seems to me that the same happens with citta-bhavana, with the purification of mind. When purification of mind goes deeper and deeper, then this state of deep balance comes into being—equanimity—and because of this balance, our true, loving and wise nature comes to the surface and manifests itself. Equanimity has a lot of sensitivity in it. Those passages from the Buddhist scriptures did not say that the disciples wouldn’t listen to the Buddha, or that the Buddha couldn’t care less, or that he was like a piece of wood; equanimity is not being like a piece of wood. The Buddha was not satisfied—there is sensitivity and warmth in equanimity; there is wisdom and warmth.