Do Fish See Water? Emotional currents in Buddhist evolution

By Nigel Wellings November 2009

Introduction

I recently read an article in Buddhadharma Spring 2009 by Rita Gross, a Buddhist historian, entitled “Why we need to know our Buddhist history”. She argues that when we join a Buddhist group we often have no understanding of how its tradition fits into the history of Buddhism as a whole and how to make sense of the contradictions that are created by the different groups differing versions of Buddhism. She says we can clarify confusions by learning a little Buddhist history. In the world of Buddhist scholarship this includes understanding the social context of the teachings, the people, their culture and the political and economic situation that gave birth to the teachings and also left its mark on them. As a psychotherapist interested in what makes us psychologically tick I would agree that this type of approach is very valuable and for our conversation this evening I want to take it a little further. I want to suggest that Early Buddhism, now represented by its one remaining school, the Theravādins, and all and each of the later Mahāyāna evolutions, were collective responses to deep emotional needs forming in the cultures they emanated from. Or put another way, each evolution of Buddhist thought started out, long before it became identifiable as a movement, philosophy or school, as a shared emotional need growing in the unconscious of the Buddhist communities. At first this need would hardly be recognised and had no name, but then very slowly small indications would become visible until something more formed would appear and finally be known as, for example, “Dharma”, “Mahāyāna Buddhism”, “Vajrayāna Buddhism”, “Pure Land Buddhism” or “Zen Buddhism”. This then is my subject this evening: how each expression of Buddhism was created by and reflects the emotional needs of the community that produce and practice it. So let us now have a look at some of at them.

Early Buddhism – rational analysis

When discussing these ideas with my wife she took against my portraying Early Buddhism as rational. For her this sounded without heart, too intellectual and dry. I can understand this but after trying to find a different word I still come back to rational. For me it captures something of Buddha’s sensible, deal with what is in front of you, approach to human suffering. When researching this talk I reread the introduction to the first book on Buddhism I bought – What the Buddha Taught by Walpola Rahula – and I think he also portrays Buddhism in this way. These are some of the things he says:

“The Buddha was not only a human being; he claimed no inspiration from any god or external power either. He attributed all his realisation, attainments and achievements to human endeavour and human intelligence.”

“Man’s position, according to Buddhism is supreme. Man is his own master, and there is no higher being or power that sits in judgement of his destiny.”

“One is ones own refuge, who else could be a refuge ………. [the Buddha said] be a refuge for oneself, never seek refuge in or from anybody else.”

From this I get a very modern feeling – it is humanistic, liberal, self-reliant, agnostic. This is a system from which any God or gods have been banished.

Rahula comments:

“The freedom of thought allowed by the Buddha is unheard of elsewhere in the history of religions. This freedom is necessary because, according to the Buddha, man’s emancipation depends on his own realisation of the truth, and not on the benevolent grace of a god or any external power as a reward for his obedient good behaviour.”

And he goes on, with examples from the early sūtras, to discuss the necessity of entertaining doubt, being ready to examine the teachings and even the Buddha himself, and also of having religious tolerance. All qualities that today we would recognise as antidotes to religious extremism and sectarianism.

So what was the society like that gave birth to this extraordinary person? What were its emotional needs that found fulfilment in the earliest Buddhist teachings?

From my reading I have built up a picture of early Aryan culture spreading down the Ganges valley from the West to the East. The religion of these people is what is now called Brahmanism which largely revolved around making sacrifices to a large pantheon of gods so to bring good weather, health, fertility and prosperity – all the things small agricultural communities need to survive. We should imagine a world constrained and yet prey to forces external to it which it tries to manage. It is vulnerable with few resources and so takes refuge in a religious mentality that depends on more powerful beings for its protection. Further more this was not a stable society, growing prosperity had created newly disposable wealth which in turn had created new centres of population with new forms of employment – governance and commerce. This urbanisation created a new group of people who had the ability to consider their situation and be dissatisfied with it. This makes sense to me; as each need is satisfied another comes to the surface. Once our bellies are full we can worry about our souls. This in fact happened to this society and a group of spiritual seekers – Samaṇas – appeared, who left the villages and the new towns and went into the still extensive forests to study with gurus and practice meditation. The historical Buddha was one of these just as was the Jains Mahāvirā. The Buddha himself describes these drop outs and the practices and beliefs they followed and what comes through is a society in spiritual expansion pushing at the edge of its religious understanding. As for the Buddha, Siddārtha Gautama, although later Buddhism would elevate his rank to that of a prince, it is more probable that he was the son of a tribal elder living on the edge of Aryan/Brahmanic culture. His willingness to adapt to individual circumstances when making rules for the Sangha, his pragmatism, his common sense and his respect for women, all suggest growing up in a community where these traits already flourished. But it is particularly his strict avoidance of metaphysical speculation that suggests his own teaching has evolved as a counterpoint to Brahmanism and also as an evolution of Brahmanic thinking. The Buddha for the first time uses the notion of karma as we know it – we reap what we sow, personal ethical action has positive consequences. And he also deconstructs the self as an unchanging essence - ātman/Brahman, the big idea in Brahmanism. When we observe our self we see that the senses are not self, the emotions are not self, the thoughts are not self, the actions are not self and consciousness is not self. We are simply an amalgam of ever changing, interconnected parts. He also ducks unanswerable questions and gives answers that skilfully respond to individual situations. He knows about the deep emotional needs in his society that this talk is about. What could be more pragmatic, more psychologically attuned, more metaphysically agnostic, more rational, that this?

Mahāyāna Buddhism – the return of the repressed god.

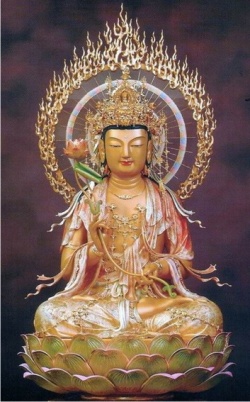

When I started thinking about Mahāyāna Buddhism the first thing I noticed was a sort of emotional warmth about it, something not immediately easy to define but definitely there. This may be because Mahāyāna Buddhism, as well as reworking and extending the understanding of emptiness, is particularly identified with the ideal of the Bodhisattva and a new cosmology where Buddha becomes a glorified transcendental being. Not a god in Buddhist terms but certainly a manifestation of timeless awakening that may be worshipped by the faithful.

It is very difficult to say when Mahāyāna Buddhism first began because it has no founder nor location. Some western scholars like to call it a ‘movement ‘ which I understand as something initially nebulous that grows in momentum as its separate identity becomes clear. Such a movement has its seeds in Early Buddhism and when it begins to stir it may have emerged within a number of groups at different locations more or less simultaneously. Bearing this in mind, Mahāyāna Buddhism becomes first visible from about 150 BCE – a hundred and fifty years before the start of our Christian era. Depending on the dating for the Buddha’s death, 480 BCE or more probably around 370 BCE, this would mean a gap of around one hundred years until Aśhoka’s coronation and then more than two hundred and fifty years, or about five generations, before a definable Mahāyāna movement can be seen. These dates are important for what I am going to suggest.

So who were the first Mahāyāna Buddhists? There is a lot of speculation about this. Some western scholars have suggested that Mahāyāna Buddhism began with members of the Buddhist laity who were discontented with their second rate spiritual status when compared to the monks. It was they who worshipped at stūpas and they who wrote the Mahāyāna sūtras that were equally objects of devotion. In fact both these practices can still be witnessed today amongst Buddhist laity. Any one visiting Buddhist stūpas such as Bodhgaya and Boudnath will see people circumambulating the stūpas as a symbol of the Buddha and in Far Eastern Buddhism particular sūtras and their ritual recitation provide the foundation for different schools.

Against this is the evidence that shows that the Sangha itself was the biggest donor to the creation and maintenance of the stūpas. Also it is far more likely that the authors of the new Mahāyāna sūtras were in fact monks with both the time and education to accomplish their task – but that they were also monks who wanted to write something that included the aspirations and needs of a laity that had gained in both influence and status. The notion of the Bodhisattva does this by moving away from valuing monastic renunciation towards the spectacular task of being a Bodhisattva in the world where one takes responsibility for ending all its woes. Good-by closeted Arhat, hello engaged Bodhisattva.

However, who ever these first clearly identified Mahāyānists may have been, my intention this evening is to go further back in time and look for the sources of Mahāyāna Buddhism much earlier. I believe we can see the emotional need for a more immediately accessible Buddha beginning to appear just a hundred years after the death of the historical Buddha. In this new conception of the Buddha he has not disappeared into the extinction of his parinirvāṇa, he now begins to be a cosmological Buddha who may still be appealed to, Brahmin like, to assist on the path to liberation. Put simply, there was something just too wonderful about the Buddha to let him go entirely, and ideas and beliefs that will eventually return him, begin to happen almost as soon as there are no more monks alive who knew someone who had known him directly. When memory gives up, imagination takes over.

I believe this process first becomes visible during the Buddhist councils held during the reign of King Aśoka – that is around a hundred years plus after the death of the historical Buddha. It is not entirely clear what happened at the second and third councils of Vaiśalī and Pāṭaliputra because accounts differ depending whether we follow a Theravāda or Mahāyāna account. According to non-Theravāda sources the council at Pāṭaliputra was convened to deal with the ‘Five Points of Mahādeva’ which broadly seem to elevate the status of the Buddha by diminishing the spiritual achievement of an Arhat. (If you remember, originally there was no distinction in their quality of awakening). The community divided over this, on one side a group called the Elders (Sthaviravādins) from whom are descended the present day Theravādins – and on the other the Mahāsamghikas – the majority of the Saṇgha who upheld the new changes and whom are more closely associated with the emerging Mahāyāna tendencies. What is particularly important here is the appearance of the Mahāsamghika teaching on the ‘supra-mundane Buddha’ which held that although the Buddha appeared as a man he was in fact a being who had been in a process of becoming a Buddha for aeons. We learn of his miraculous birth, that he merely appears to wash, eat, sit in the shade, take medicine etc. so to conform with the world but in reality he never sleeps, is always in meditation and is omniscient and so on. All of which is very close to the Mahāyāna teaching that at the Buddha’s death he does not actually become extinct – disappearing for ever – but, because of his great compassion, he remains available to us through prayer. What we are seeing here is the actual process of the Buddha’s deification – not as a Buddhist god who suffers impermanence – but as something much more – an uncreated, undying principle of Buddhahood which the historical Buddha is but one Avatar of. Before it was believed that the Buddha at death entered an inexplicable state that defied explanation, except it was clear that he was no longer present. Now with the introduction of the idea of a supra-mundane Buddha comes the notion that the Buddha’s body, while seeming to be that of an ordinary human, also contains the Buddha’s spiritual nature which is his body of truth – his Dharmakāya. From here it is now only a step away to universalise the presence of this body of truth and we have a supra-mundane Buddha who has been present from beginning-less time and who permeates to entire phenomenal universe. The earlier repudiated and vanished Brahman, returned in all but name?

Aśoka died about 232 BCE and from this time alternative conceptions of the Buddhist spiritual path and its goal begin to emerge that will later crystallise as the Mahāyāna. What is perhaps more important though, for us this evening, is that with Aśoka, Buddhism was drawn closer to the state and secular living. It comes in from the forest and becomes more exposed to the theistically orientated spiritual needs of the population who are not cognisant of the Buddhist deconstruction of the illusion of a permanent self. From the same population theistic devotional Hinduism also begins to emerge immediately after the death of Aśoka, as does the growth of early Buddhist sculpture that evolves into representing the Buddha as a solar god by around the first century CE. It seems to me that the majority of the population of largely uneducated farmers, have not really moved on from pre-Buddhist days and, like their ancestors, require a form of spirituality that can provide solace for their hardships. Buddhism initially questioned the assumptions of this simpler faith, but now, as it reaches out and engages more with a faith based Buddhist laity, it has to meet their emotional needs and they want their gods.

Tantric Buddhism – Buddhism under siege

It is not a coincidence that political upheaval, progressively aggressive Islamic incursions and the appearance of Tantrism simultaneously occur. We now take a leap forward in time to the seventh century CE and early Medieval Buddhism. In the preceding centuries, under a series of relatively stable and benign Central Asian and Indian dynasties, Buddhism had become a powerful and influential spiritual force. The great Indian monastic universities such as Nalanda had been built and were functioning, creating Buddhist monks who brought qualities such as stability, compassion and decorum to an all too easily bloody and querulous world. However, this ability was gradually undermined. The Indian political scene began to fracture into small principalities, often not much more than lands held by Mafia like brigands, and from the West came Islam, first as raiding pirates along the coast, and then later, as armies bent on destruction, putting whole cities to death or selling them into slavery. Further more, the militant worship of Śiva, the Hindu principle of destruction, was pushing up from its home in South India, offering to the violent new war lords an icon as violent as themselves that also legitimised their distinctly non-Buddhist values and behaviours. In the face of this combined onslaught Buddhist patronage, necessary for the maintenance of its monasteries, began to decline. First the Buddhist mercantile class and the craft guilds began to suffer in the unstable political and economic climate. Then the kings themselves began to shift their allegiance from Buddhism to the newly vibrant Hindu revival. Within four hundred years Buddhism was largely extinct in the land of its birth.

In the face of this challenge Buddhism adapted and changed. From within the Buddhist laity and the monasteries the figure of the tantric siddha began to emerge. Buddhism had started out in the forests and had for a long while existed on the edge where forest and cultivated lands met. Monks crossing over each day with their begging bowls, laity going to seek counsel and solace. However these new yogins were like nothing known before. Virtually naked except for ornaments, musical instruments and drinking utensils made from human bone, they clustered in charnel grounds at the edge of society. Breaking all the taboos of both Hindu and Buddhist communities they made sex sacred, offered blood sacrifices and ate and drank all that was filthy and obscene. They were holy shockers! They were also politically astute and, sharing much of the same tantric culture of their Hindu Śaivite cousins, could vie with them in the courts of kings. At first they must have been repellant to the urbane and highly educated monastic hierarchy. We know many siddha’s came from lowly, uneducated backgrounds. Fish sellers, arrow makers, people of low caste. However, by the time Indian Buddhism was all but finished and had escaped over the Himalayas into the safety of Tibet, the mad and scary tantricism had been tamed and institutionalised into the monasteries and its new meditative practices elevated to the most powerful means to achieve enlightenment.

This is a hugely complicated story which we do not have time for but Ronald Davidson, in a fascinating book about the social history of tantrism, demonstrates how Buddhist practitioners – monks and siddhas – took on the imperial culture of their time, mirroring kingship and the exercise of power. Drawing parallels he says that the process of becoming a king and the kingly activities that follow are echoed by the process of becoming a tantric practitioner and living the yogis life. The prince obtains coronation, the practitioner initiation. The prince recognises he is semi-divine holding dominion over surrounding vassel states. The practitioner recognises he is the deity at the centre of the maṇḍala. The prince enters a circle of counsellors, the practitioner a circle of vajra brothers and sisters. The prince is protected by his army, the practitioner by Dharma Guardians. The prince engages in peaceful and aggressive royal acts, the practitioner engages in peaceful and wrathful tantric rituals. Thus at a time when kings were creating a political landscape where each surrounded himself with smaller satellite states, Buddhism developed a new representation of the spiritual landscape as a maṇḍala which had at its centre a principle deity surrounded by secondary deities. These maṇḍalas, the creation of the siddhas and recorded in there new texts – tantras, responded to threats to society and the collective anxieties these threats created. Both siddhas and kings sought control through magical means whether it be over the deluded mind or the socio-economic chaos and together they conspired to use the new magical technology of Tantrism to keep the forces of their mutual destruction at bay. Not for no reason do we see in the Buddhism of this time the inclusion of terrifying wrathful deities from Hinduism. Buddhism was on the back foot and any skilful means was welcome if it would keep it intact just a bit longer. Put simply, when in a corner we fight back.

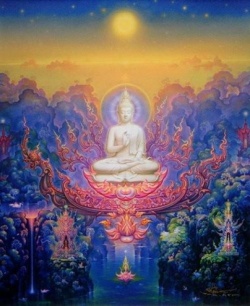

Pure Land Buddhism – Our Lord and Saviour of Mankind

This last example I feel is particularly clear and for me represents the biggest shift in Buddhism from its inception. It is almost as if a new archetype takes over in the Pure Land Buddhism of China and the Far East that has more in common with Christianity and the devotional cults in Islam and Hinduism. An archetype that makes us a powerless sinner who may only be saved by the grace of a Being of light – Amitābha. Seemingly gone is the notion that we must be our own refuge, now it is too late for that and our salvation is no longer in our own hands.

Buddhism entered China by the silk roads around 50 CE. Here it met a sophisticated literate society of scholar administrators with their own developed systems – Confucianism and Taoism – governing a vast class of peasant farmers. Again this is a long history of ups and downs for Buddhism as it adapts to survive in the economic and political upheavals. In this melting pot Pure Land Buddhism became the most popular form of Buddhism for the labouring laity promising entry to the “Happy Land” heaven of Sukhāvati for those who only need remember the mantra of Amitābha, the Buddha of Light, minutes before their death. For those powerless to change the grinding and unremitting circumstances of their lives this must have been a powerful message of hope. A message of hope that, in CE 549 – the date the Chinese believed the age of Buddhist decline began – Tao-ch’o, the second patriarch compounded. He declared that we had now entered a time so spiritually degenerate that we could no longer follow the path of the Bodhisattva based on accumulating the six perfections but instead must rely on the easier path of devotion to Amitābha. Now it was Amitābha who would save us from our suffering and not our own, now ineffectual, efforts. Effectively we had become children reliant upon a benevolent parent and no longer an adult responsible for our own salvation. Amitābha, our Lord and Saviour of mankind.

Conclusion

So we have seen in this quick and patchy psychoanalysis of Buddhist social history a process that begins with a movement towards a self-reliance that takes us out of the hands and whims of the early Vedic gods and which then, in a series of steps over the next thousand years, seems to redeposit us, equally as helpless, back in the hands of Buddhist ‘gods’ in all but name. The big human emotions are present throughout, the longing for safety, solace and comfort from someone bigger than ourselves who can protect us from a world of suffering. Also smaller themes emerge – our genius for creative and pragmatic adaptation, our fertile imaginations, our endless thirst for spirituality – even if it is a spirituality that the earliest expression of Buddhism seems to have critiqued negatively. My own feeling is that of wonder and awe. At our best we are amazing beings and if we accept the notion of skilful means then all this ducking and diving to keep the Buddhist vision alive is an entirely legitimate Buddhist pursuit. It demonstrates that at the heart of things the Buddha Nature is always in expression.

And we can take it further still; history is to learn from. If my idea holds water, that all the evolutions of Buddhist thought and practice represent solutions answering collective emotional needs, then we can translate this principle to the present. The question then is what do we collectively yearn for and what sort of Buddhist solution will this yearning be the causes and conditions for? The future Buddhism of the West already lays in our unconscious.

References

Ronald M. Davidson (2002) Indian Esoteric Buddhism, A Social History of the Tantric Movement, Columbia University Press, New York

Walpola Rahula (1967) What the Buddha Taught, Gordon Fraser, Bedford

General Background Reading

Peter Harvey (1990) An Introduction To Buddhism, Teachings, history and practices, Cambridge University Press