Hopi Indian and Tibetan similarities

From the Roof of the World to the Land of Enchantment:

The Tibet-Pueblo Connection

Excerpt by Antonio Lopez

In the incongruous atmosphere of the Wilshire Hotel in Los Angeles, an extraordinary encounter took place in 1979. During the Dalai Lama's first visit to North America, he met with three Hopi elders. The spiritual leaders agreed to speak in only in their Native tongues. Through Hopi elder and interpreter Thomas Benyakya, delegation head Grandfather David's first words to the Dalai Lama were: "Welcome home." The Dalai Lama laughed, noting the striking resemblance of the turquoise around Grandfather David's neck to that of his homeland. He replied: "And where did you get your turquoise?"

Since that initial meeting, the Dalai Lama has visited Santa Fe to meet with Pueblo leaders, Tibetan Lamas have engaged in numerous dialogues with Hopis and other Southwestern Indians, and now, through a special resettlement program to bring Tibetan refugees to the United States, New Mexico has become a central home for relocated Tibetan families. As exchanges become increasingly common between Native Americans and Tibetans, a sense of kinship and solidarity has developed between the cultures. While displacement and invasion have forced Tibetans to reach out to the global community in search of allies, the Hopi and other Southwestern Native Americans have sought an audience for their message of world peace and harmony with the earth. In the context of these encounters are the activities of writers and activists who are trying to bridge the two cultures. A flurry of books and articles have been published, arguing that Tibetans and Native Americans may share a common ancestry.

The perception of similarity between Native Americans of the Southwest and the Tibetans is undeniably striking. Beyond a common physicality and turquoise jewelry, parallels include the abundant use of silver and coral, the colors and patterns of textiles and long braided hair, sometimes decorated, worn by both men and women. When William Pacheco, a Pueblo student, visited a Tibetan refugee camp in India, people often spoke Tibetan to him, assuming that he was one of them. "Tibetans and Native American Pueblo people share a fondness for chile (though Tibetans claim pueblo chile is too mild!)," says Pacheco, "and a fondness for turquoise, used by both cultures as ways to ward off evil spirits. Also, the prophecy of Guru Rinpoche, when he said, 'when Tibetans are scattered throughout the world, and horses run on iron wheels and when iron birds fly, the dharma will come to the land of the red man.'"

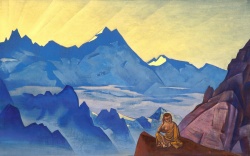

Even before most westerners knew where Tibet was, much less what their situation was, and almost twenty years before the advent of the Tibetan Diaspora, cultural affinities between these two peoples were noted by Frank Waters in his landmark work, Book of the Hopi (1963). Waters' analysis went below the surface, citing corresponding systems of chakras or energy spots within the body meridians that were used to cultivate cosmic awareness. In The Masked Gods, a book about Pueblo and Navajo ceremonialism published in 1950, Waters observed that the ZuÃ’i Shalako dance symbolically mirrored the Tibetan journey of the dead. "To understand [the Shalako dance's] meaning, we must bear in mind all that we have learned of Pueblo and Navaho eschatology and its parallels found in the Bardo Thodal, The Tibetan Book of the Dead, in The Secret of the Golden Flower, the Chinese Book of Life, and in the Egyptian Book of the Dead." As is the case with most Earth-based cultures with a shamanic tradition, some Native ceremonies contain spiritual motifs similar to cultures from around the world (hence the broad comparison made by Waters). This could account for some of the similarities seen between Tibetan and Native American spiritual practices, such as Navajo sand painting, and cosmic themes found throughout traditional Pueblo dances.

Interview with Lorain Fox Davis and Tsultrim Allione on

CONNECTIONS BETWEEN BUDDHISM AND NATIVE AMERICAN PRACTICES

(originally appeared in Inquiring Mind; www.inquiringmind.com)

TSULTRIM

I've always felt it's crucial for American Buddhists to relate to the spirits of this new homeland of dharma. It was not until Padmasambhava had connected with the local spirits of Tibet that Buddhism was able to take root there. For us the Native Americans are the people that hold this relationship with the spirits of the land and the elementals.

My connection with Native American people goes back to my childhood in New Hampshire when my family lived in a house that was previously owned by a Lakota man, Charles Eastman, who was educated at Dartmouth College and was the doctor at the battle of Wounded Knee. He was a mythic presence in my childhood. Years later, while I was living on the East Coast, I began participating in many Native American sweats and vision quests.

Tara Mandala, the Tibetan Buddhist retreat center I started in Colorado, adjoins on Ute land. When we first arrived in 1994, Bertha Grove, a Ute medicine grandmother, came to conduct ceremonies. Over the years Bertha Grove and other Ute elders as well as Lakota teachers like Arvol Looking Horse, Nineteenth Generation Holder of the White Buffalo Calf Pipe, have continued to do ceremonies connecting to energies of our land. The Tibetan lamas who have come to Tara Mandala have been very interested in meeting the Native American elders. I've led retreats with teachers of Native American spirituality including Lorain Fox Davis who also practices Tibetan Buddhism and teaches Native Studies in the Environmental Department at Naropa University.

LORAIN

My path spans both Native American and Tibetan spirituality. On my mother's side, I'm Cree and Blackfeet-Cree from Canada and Blackfeet from Montana. I studied for many years with a traditional Lakota teacher, Irma Bear Stops. While it is rare for women to Sundance, Irma was a very respected Sundancer. Although I wasn't Lakota, she introduced me to Lakota spirituality and I was honored to dance by her side for seven years at Pine Ridge, South Dakota. My husband and our oldest son danced there also. My son and one of our daughters have returned to our Blackfeet ways and they Sundance in Montana. It is a challenging and humbling, yet deeply harmonious way of life to follow these traditions based in nature and the elements. We all need to come back in balance with our ancient connections with Mother Earth.

I was introduced to Tibetan Buddhism over thirty years ago and my primary Tibetan Buddhist teacher is Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, who married my husband and I when he came to Crestone, Colorado in 1981. We were living in Santa Fe at the time and we were invited to join his traveling entourage. He was a great teacher of gentle compassion and wisdom. Since that time we have lived here in Crestone, where several Buddhist Centers have been founded in the past few years.

There is a great similarity between Native American spirituality and the Tibetan Buddhist teachings of compassion and respect for every living creature. This respect for all life is what I learned from my Cree grandmother when I was a child. There are many Tibetan teachers who come through here and I try to attend their sessions. They are grounded in the environment, and they have ceremonies similar to ours of burning cedar to invite and honor the spirits-the spirits of the mountains, the spirits of the water, the Elemental Beings and the great Thunderbird who brings the rains of purification and regeneration. The spiritual power of thunder and lightning is central to both Native and Buddhist traditions. These ancient traditions hold that Thunder Beings are the spiritual and physical manifestations of Spirit.

TSULTRIM

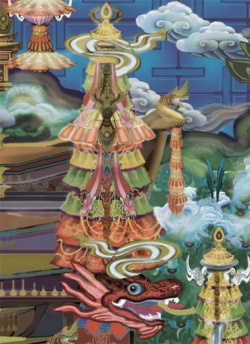

Some of the Tibetan Buddhist practices and most of those of Native American are grounded in relationship to the elements and all beings. The Tibetans have a smoke offering ceremony called Sang in which you make a fire and then put juniper branches and other offerings like grains, honey and milk products to make smoke. You see the smoke from that fire turning into offerings for all beings. The Native Americans also use smoke from cedar and age for purification.

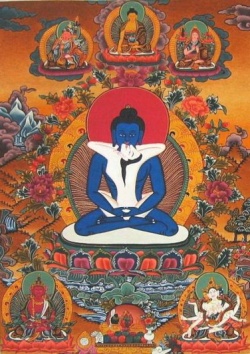

For me, the sweat lodge, or Stone People's Lodge, is a bit like the Tibetan Buddhist Mandala. The Mandala is a template of the enlightened mind based on the center and the four directions. In the lodge there are four directions and four rounds (sessions of prayer; each round has a different meaning. During the sweat, you go through a process of death and rebirth. When you enter the lodge, you shed everything, and then during the four rounds in your praying you touch in on every aspect of your being. When you come out, you are symbolically reborn. Both the mandala and the sweat lodge ceremony are centered in a physical mandala of the universe; both are deeply transformative architectures for the psyche.

The Stone People's Lodge and Tibetan Buddhism both include teachings of the integration of masculine and feminine. The sweat lodge, shaped like a turtle shell, is placed in front of the fire with a small Tree of Life in between them. The lodge symbolizes the feminine womb of rebirth, and the fire the masculine. The Tree of Life symbolizes what is born from that union. Rocks are heated in the fire and are brought past the Tree of Life into a pit in the center of the lodge. In Tantric Buddhism, one of the primary symbols is the union of the masculine, representing skillful means, and the feminine, representing wisdom. Their sexual union represents the non-dual state, like the union of the fire and the womb in the lodge.

LORAIN

The underlying theme in Native American spirituality, as well as most Indigenous spirituality, is to honor the sacredness of the great circle of life. Sacred circles, medicine wheels, and mandalas are images that direct us to the center of our being, to the truth of who we are. Within the sacred circle of "everything that is" we begin to remember our relationship with all life. We recognize our relationship with Father Sun and Mother Earth and the Great Spirit, Creator. It becomes obvious that we are all related brothers and sisters in one great family, not just our human family. The Indian Elders say, " we must remember also the four footed, those who swim and those who fly, those who crawl and those who move very slowly like the stone people and all the green and growing things". Within this sacred circle we are one. What we do effects everyone, everything. These great teachings remind us of our responsibility to care for all life. In our pursuit of progress and comfort we have separated ourselves from our place in this great circle. Earth traditions bring us back in harmony and balance within the circle.

The Sundance of the Plains Indians is the center of our spiritual traditions. It is a ceremony of sacrifice and thanksgiving honoring the sacredness of the circle of life. From sunup to sundown, each day for four days they dance and fast-without food, or water. Each day the four major races of people are prayed for; children, adolescents, adults and elders are prayed for; those who swim, fly, crawl, the green and growing things, and the stone people are prayed for; each of the four sacred directions, the powers of those directions, and the elements are prayed for. Everything is brought together in the circle, all living things are danced and sung for. In the center of the circle is the Tree of Life, {the axis mundi, that which connects the heavens and earth}; and the people dance around her. They dance and sing and focus on "all our relations, and our humble place in the circle of life". For four days the dancers pray for all of creation first, before they include themselves. The Lakota end all prayers with " O MITAKUYE OYASIN" meaning "I do this for all my relations (or all sentient beings)."

TSULTRIM

Like the ceremonies of Tibetan Buddhism, the Native American ceremonies open to an experience of non-duality, but the methods for accessing this experience are different. The Indians get there through a direct relationship with earth, sun, moon and the great spirit. Dualism happens when egocentricity develops, creating a split with nature, each other and all life. When I was leaving for a year retreat in the Tibetan Buddhist tradition, I told the medicine woman Bertha Grove, "I'll be alone for a long time." She replied, "You're not going to be alone. When you go outside and look around, you won't feel alone at all. You'll be completely accompanied by the trees, the plants, the birds and the animals." For many years, I had learned about non-duality and the teachings of integration, but Bertha Grove's way of saying it was like a direct transmission.

In both the Tibetan and Native American traditions, inside and outside are ultimately not experienced as separate. You form a truly interactive relationship with the environment. For example, you're walking outside and you have a question in your mind. Then a raven flies over and crows three times. For most Americans that event would have no meaning; But for a Native American person, that could be a direct answer to a question which would be understood because of his or her experience of the interconnected world; in other words, there's no 'out there' out there.

The Tibetans also have an interpretive relationship with the phenomenal world that stems from insight into the interdependence of all phenomena called tendrel. When the world is perceived in this way, things that happen are seen as 'signs.' Take the example of the raven flying and crowing three times. In Tibet, there's a whole divination system based on the calls of the ravens, how many times they call and from which direction they're flying. You're actually living in a world which is responding to you and to which you are constantly responding, rather than one in which there's you who is alive and then everything else which is more or less irrelevant and unresponsive. One aspect of awakening in Buddhism is an experience of this dynamic interdependence.

Lorain Fox Davis (Cree/Backfeet) is Adjunct Faculty for the American Indian Studies Program and on the Advisory Council for the Environmental Studies Department at Naropa University. She is founder/director of Rediscovery Four Corners, a non-profit organization that serves Native American youth and elders.

Tsultrim Allione spent several years in the Himalayas as a Tibetan Buddhist nun. She later disrobed and wrote Women of Wisdom, a groundbreaking book on women in Buddhism. In 1993 she founded Tara Mandala a retreat center in Colorodo.