Rebirth of Cave Buddhas by HOLLAND COTTER

In the Buddhist way of thinking, all things must pass, though it seems a shame when they do, especially if they’re out-of-this-world beautiful, as so much Chinese Buddhist art is. But could that vision of transience be changing in the 21st century, as technology lets all kinds of things, including art, live on forever out there in digital clouds?

Regret and hope alike run through the multifaceted exhibition “Echoes of the Past: The Buddhist Cave Temples of Xiangtangshan” at New York University’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World on the Upper East Side. The show is, at heart, a salvage operation, an effort — and a moving one — to reassemble a specific body of art now scattered, revivify a place of origin beaten down by depredation, and point to a plausibly upbeat future. In important ways it meets these goals and reboots history.

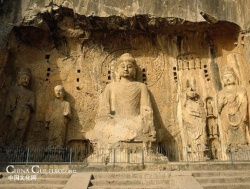

In the sixth century A.D. a short-lived dynasty known as the Northern Qi (A.D. 550-577) excavated a series of Buddhist cave temples from limestone cliffs in northeast China. The caves, in two main clusters several miles apart, were collectively called Xiangtangshan, meaning “mountain of echoing halls.” They were filled with carved figures — some free standing, some cut in high relief from living rock — that have long been considered among the most sublime images in Chinese art. From the dozen examples on display in this show you see why.

The three oldest caves, referred to by archaeologists as the northern group, are also the grandest, being imperial commissions. One is genuinely king size, its roomy interior dominated by Buddhas and bodhisattvas 20 feet high.

The caves in the other group, the southern group, are more modest in scale. Their figures are merely life size but conceived in a transcendently sophisticated, courtly style.

Stylishness was important. These shrines were meant as permanent records of dynastic taste and spending power on earth. And they projected that taste and power into the afterlife, in the hopes it would insure their patrons V.I.P. treatment there.

Whatever the standing of the Qi in paradise, the art left behind at Xiangtangshan (pronounced shahng-tahng-shahn) was unlucky. Time and weather ate away at the caves. Over the centuries political turmoil took a toll. But the most concentrated damage seems to date from after 1900 and the rise of an international market for ancient Chinese Buddhist sculpture.

The Chinese themselves weren’t collectors: to them such objects were either sacred and beyond aesthetics, or bizarre relics of an imported religion that had nothing essentially Chinese about it. The attitude in the West, and in Japan, was different.

After photographs of spectacularly decorated cave temples at Yungang and Longmen began to circulate in Paris in 1909, a feeding frenzy set in. In China looters got to work, dragging sculptures out of caves and hacking away at reliefs, chopping heads off Buddhas, slicing off hands.

Xiangtangshan was a natural target, though one of primarily local renown. Because photographers hadn’t found it, it wasn’t a celebrity site, didn’t have brand value in the West. Once a sculpture left its caves, few people could trace its source.

Into the late 20th century the situation stayed grim. Xiangtangshan, though still a pilgrimage destination, was in ruins. Much of its art was gone, scattered around the world, hugely admired but little studied. The site’s future, like its recent past, looked bleak, if not hopeless.

The 21st century has brought a turnaround, partial but significant, in its fortunes. In 2004 the Center for the Arts of East Asia, at the University of Chicago, initiated an ambitious project devoted to the site. Led by Katherine R. Tsiang, the center’s associate director, it had several aims: to identify the existing corpus of Xiangtangshan sculpture in museums and private collections worldwide; to photograph as many of these objects as possible with 3-D scanning; and to insert these images within digital reconstructions of the caves they came from.

The result is the adroit mix of art, history, international diplomacy and new technology found in the New York show, which is an edited version of one seen earlier at the Smart Museum of Art at the University of Chicago, and at the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington. Several sculptures have been left out along the way, but concision has value of its own. The installation at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World, overseen by Peter De Staebler, is trim, focused and extremely effective.

The centerpieces are five fragments from the grand early imperial cave in the northern group, though “fragments” hardly seems the word for carvings that, though incomplete, have the heft of monuments. They include a pair of immense heads cut from bodhisattvas that flanked one of the cave’s three giant seated Buddhas. From one of those Buddhas comes a set of detached hands; from another a sliced-off, beatifically smiling face.

One by one the pieces are mightily impressive. And when a sense of the scale of the figures they came from kicks in, they can take your breath.

Four smaller life-size Buddhist deities, all from the southern cave group, are gripping for different reasons, beginning with the Fabergé-esque extravagance of their bangles-and-beads attire. One figure, though, is different from the others. He’s dressed like a monk, not a prince, and holds something large and curved between two upright hands. It’s probably a lotus bud, though it could just as easily be his heart plucked from his chest and offered, still warm, for our perusal.

This sculpture has been in the collection of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology since 1916, when it was bought from a Chinese dealer. But what would its gesture, so clearly symbolic, have conveyed in its original cave setting, in the company of many other gesturing figures? What intended narrative of compassion or salvation might we discern in that context?

This is the sort of question that Ms. Tsiang and her Chicago colleagues are trying to approach through digital technology. A small gallery has been set aside in the show for a 3-D digital projection that reconstructs the interior of one of the Xiangtangshan caves by inserting images of dispersed sculptures back into video of their original places.

The effect is a little odd. The reinserted items, all colored bright yellow, resist visual integration into the setting. But the idea is a good one. More effective, however, is the kinetic effect of the video as a whole, which immerses you in the cave and gives you a sense of moving through it, looking around.

Such simulations may well be the wave of the museological future in China, at least in the case of archaeological environments too fragile to withstand tourist traffic. At the great Buddhist cave temple complex at Dunhuang, in northwestern China, for example, plans are under way to create an enormous visitor center that will make walk-in digital versions of the painted caves a substantial part of a visitor’s experience.

And surely some of the ancient underground tombs being discovered in China today, particularly those with wall paintings, will be publicly available only at a digital remove, which could mean on the Internet.

Needless to say, there are gains and losses built into the process of balancing access and conservation, though the issue at stake in the case of the Xiangtangshan project is a different one. Here the aim is not so much to prevent an existing environment from vanishing but to reclaim one already largely gone. And the exhibition puts this across.

The sculptures in the gallery magnificently speak of a wholeness forever passed, while the “digital cave” promises an integrative reality in progress, still to come. And that reality has its own enchanting images: of art that is composed, or recomposed, from networks of coordinate lines that suggest cosmic connectors, and from pixels that, like molecules, come together, and fall apart, and come together again, in a play of change and not-change that Buddha himself might give a nod to. [1]