The Canon

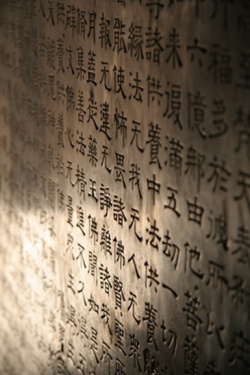

The Tripitaka (Sanskrit) (Pali: Tipitaka) is the Canon of the Buddhists, both Theravada and Mahayana. Thus it is possible to speak of several Canons such as the Sthaviravada, Sarvastivada and Mahayana as well as in term of languages like Pali, Chinese and Tibetan. The word is used basically to refer to the literature, the authorship of which is directly or indirectly ascribed to the Buddha himself.

It is generally believed that whatever was the teaching of the Buddha, conceived under Dhamma and Vinaya, it was rehearsed soon after his death by a fairly representative body of disciples. The later systematised threefold division, into Sutta, Vinaya and Abhidhamma is based on this collection. Sharing a common body of Dhamma and Vinaya, the early Buddhist disciples appear to have remained united for about a century.

The Council of Vesali or the second Buddhist Council saw the break up of this original body and as many as eighteen separate schools were known to exist by about the first century B.C. It is reasonable to assume that each of these schools would have opted to possess a Tripitaka of their own or rather their own recension of the Tripitaka, perhaps with a considerably large common core.

It has long been claimed that the Buddha, as he went about teaching in the Gangetic valley in India during the 6th and 5th centuries B.C.E., used Magadhi or the language of Magadha as his medium of communication. Attempts have been made to identify this Magadhan dialect with Pali, the language in which the texts of the Sthaviravada school are recorded. Hence we speak of a Pali Canon, i.e., the literature of the Sthaviravadins which is believed to be the original word of the Buddha.

At any rate, this is the only complete recension we possess and the Pali texts seem to preserve an older tradition much more than most of the extant Buddhist works in other languages.

Further, the Sthaviravadins admit two other major divisions of Pali Buddhist literature which are non-Canonical. They are:

- 1. Post-Canonical Pali literature including works like Petakopadesa and Milindapanha, the authorship of which is ascribed to one or more disciples.

- 2. Pali Commentarial literature which includes:

- (a) Atthakatha or Commentaries, the original version of which is believed to have been taken over to Sri Lanka by Thera Mahinda, the missionary sent by Asoka and

- (b) the different strata of Tika or Sub-Commentaries, contributions to which were made by Buddhist monks of Sri Lanka, India and Burma.

Besides this Pali recension of the Sthaviravada school there are fragmentary texts of the Sarvastivada or of the Mulasarvastivada which are preserved in Sanskrit. A large portion of their Vinaya texts in Sanskrit is preserved in the Gilgit manuscripts. But a more complete collection of the Sarvastivada recension (perhaps also of the Dharmapuptaka and Kasyapiya), i.e., a Sanskrit Canon, must have possibly existed as is evident from the Chinese translations preserved to us. These include complete translations of the four agamas (the equivalent of the Pali nikayas). Of the Ksudraka (Pali: Khuddaka), only some texts are preserved in Chinese.

In addition to these, the Chinese translations seem to preserve, to the credit of the Sarvastivadins, a vast Vinaya literature and an independent collection of seven Abhidhamma treatises. Thus what could be referred to as a Sarvastivada Canon ranges between fragments of texts preserved in Sanskrit and the more representative collection of the Tripitaka preserved in Chinese. It may be mentioned here that a version of the Mulasarvastivada Vinaya consisting of seven parts, even more faithful than the Chinese version, is preserved in Tibetan. Of the Abhidharma collection only the Prajnaptisastra appears to have been translated into Tibetan.

Speaking further of the Tripitaka in terms of language we have in Chinese different recensions of the Canon (preserved in part) belonging to different schools. These recensions are primarily based on the Tripitaka of Indian origin. In addition to the ancient texts which these recensions preserve they also contain independent expositions of the early doctrines or commentarial literature on them.

The Chinese Canon preserves the Vinaya texts of as many as seven different schools. In place of the division into ‘canonical groups’ of Sutra, Abhidharma and Vinaya, this new arrangement seems to reckon with a live and continuous tradition in accepting as authoritative both the Sutra (or words of Buddha) and Sastra (or commentaries, treatises, etc. of disciples of a later date).

It becomes clear from the foregoing analysis that in speaking of a Buddhist Canon one has to admit that it is both vast in extent and complex in character. While the earlier and more orthodox schools of Buddhism reserved the term Canonical to refer to the Body of literature, the greater part of which could be reasonably ascribed to the Buddha himself, other traditions which developed further away from the centre of activity of the Buddha and at a relatively later date choose to lay under the term Canon the entire mosaic of Buddhist literature in their possession, which is of varied authorship and is at times extremely heterogeneous in character.

The First Rehearsal of the Tipitaka

After the Final Extinction (Parinirvana) of the Buddha, and the cremation of his body, the community of monks chose five hundred Arahants ('worthy ones', 'perfected ones') to work together to compile the doctrine and the discipline, in order to prevent the true doctrine from being submerged in false doctrines. Each of the recensions of the Vinaya now available contains an appendix which narrates how one of the senior monks, Mahakasyapa, presided over this assembly, which worked systematically through everything the Buddha was remembered to have said and produced an agreed canon of texts embodying it.

The versions differ over the details but agree in broad outline. The Arahants met in Rajagrha, since that great city could most easily support such a large assembly for several months. The organisation of the Buddhists tended to centre on great cities as it was apparently not possible in any other way to convene a meeting large enough to be authoritative for the entire community, given its democratic constitution.

Ananda, who being the Buddha’s personal attendant, had heard the discourses more than anyone else, first recited the ‘doctrine’ (dharma). Mahakasyapa asked him about all the dialogues, etc., he remembered and the assembly endorsed his versions as correct. The doctrine compiled in this way became known as the Sutra Pitaka, the collection of sutras (the term pitaka probably signifies a 'tradition' of a group of texts). The discipline was similarly recited by Upali, a specialist in that subject, and codified as the Vinaya Pitaka. On the third pitaka (Abhidhamma) which should make up the Tipitaka ('Three Pitakas') there is disagreement.

The Sthaviravada and Mahasamghika versions do not mention its recitation, and since the agreement of these two schools should establish the oldest available textual tradition it appears that originally there were only two Pitakas. However, even the Mahasamghika account mentions the Abhidhamma as among the texts handed down after the rehearsal. The Mahisasaka version makes no mention of a third Pitaka.The Sarvastivada and Dharmaguptaka Vinayas on the other hand have Ananda reciting the Abhidhamma as well as the Sutra. The Kasyapiya (=Haimavata) mentions the Abhidhamma Pitaka without saying who recited it.

A later text of the Sarvastivada School, the Asokavadana states that Kasyapa recited the Matrka or Matrka Pitaka (two versions of the text). The same tradition is found in the Vinaya of the Mula Sarvastivada School, a late offshoot of the Sarvastivada which thoroughly revised and enlarged its Tipitaka. 'Whether a Matrka or Abhidhamma was actually recited at the First Rehearsal or not, all the early schools were equipped with a third, Abhidhamma Pitaka.

According to the consensus of the schools the Sutra Pitaka was arranged in five agamas, 'traditions' (the usual term, but the Sthaviravadins more often call them nikayas, 'collections').

The order also is generally agreed to be as follows:

(1) Digha Nikaya. ('Long Tradition', about 30 of the longest sutras); (2) Majjhima Nikaya ('Intermediate Tradition', about 150 sutras of intermediate length; the short sutras, the number of which ran into thousands, and were classified in two Ways as) (3) Samyutta Nikaya ('Connected Tradition', sutras classified by topic, for example the sutras on conditioned origination); (4) Anguttara Nikaya ('One Up Tradition', sutras on enumerated items classified according to the numbers of the items in sections of ones, twos, threes . . . up to elevens) ; (5) Khuddaka Nikaya (outside the first four Nikayas, there remained a number of texts regarded by all the schools as of inferior importance, either because they were compositions of followers of the Buddha and not the words of the Master himself, or because they were of doubtful authenticity, these were collected in this 'Minor Tradition').

This order of the five 'traditions' happens also to be the order of their authenticity, probably because it was easier to insert short texts among a large number or to get a composition of doubtful origin admitted to the already doubtful Minor Tradition of a school.

This is soon ascertained by comparing the various available recensions.

It has been suggested that some schools did not have a [[Minor Tradition at all, though they still had some of the minor texts, incorporated in their Vinaya, hence the 'Four Nikayas' are sometimes spoken of as representing the Sutras.

The most noticeable feature of the Minor Tradition is that its texts are for the most part in verse as opposed to the prevailing prose of the rest of the Tipitaka. In other words, whatever else may be said about their authenticity, they are poetic compositions which may stimulate interest in the doctrine but are as remote as possible from being systematic expositions of it.

We have naturally ignored them in investigating the teaching of the Buddha, but they are of much interest in themselves, as literature, and in connection with the popularisation of Buddhism in the centuries following the parinirvana when in fact many of them were composed.

The First Rehearsal is recorded to have taken place during the rainy season of the first year after the parinirvana, the latter event being the era from which the Buddhists have reckoned their chronology.

It does not now appear to be possible to determine the exact extent and contents of the Tipitaka thus collected, in fact as we have seen it may at first have consisted of only two pitakas, not three, namely the Doctrine and the Discipline.

It is clear that some texts were subsequently added, even before the schisms of the schools, for example the account of the First Rehearsal itself, an account of a second such rehearsal a century later and a number of sutras which actually state that they narrate something which took place after the parinirvana or which refer to events known to have taken place later.

It is interesting that the account in the Vinaya records that at least one monk preferred to disregard the version of the Buddha's discourses collected at this rehearsal and remember his own, as he had received it from the Buddha.

This was Purana, who returned from the South after the Rehearsal. The elders invited him to possess himself of the collection rehearsed but he politely declined. If there were a number of monks in distant parts who missed the First Rehearsal it is likely enough that quite a number of discourses remembered by them and handed down to their pupils existed, which were missed at the Rehearsal though perfectly authentic. Under these conditions it would seem reasonable to incorporate such discourses in the Tipitaka later, despite the risk of accepting unauthentic texts.

The Mahaparinirvana Sutra makes the Buddha himself lay down a rule to cover just this situation: if someone claims to be in possession of an authentic text not in the Sutras or in the Vinaya - again two pitakas only - it should be checked against the Sutra and Vinaya and accepted only if it agrees with them.

Such agreement or disagreement may have seemed obvious enough at first. Later it was far from obvious and depended on subtle interpretations; thus the schools came to accept many new texts, some of which surely contained new doctrines.

It appears that during the Buddha's lifetime and for some centuries afterwards nothing was written down: not because writing was not in use at the time but because it was not customary to use it for study and teaching. It was used in commerce and administration, in other words for ephemeral purposes; scholars and philosophers disdained it, for to them to study a text presupposed knowing it by heart.

To preserve a large corpus of texts meant simply the proper organisation of the available manpower. 'Few monks at any period seem to have' known the whole Tripitaka.

The original division of the Sutras into several agamas, 'traditions', seems primarily to have reflected what monks could reasonably be expected to learn during their training.

Thus in Sri Lanka, at least, in the Sthaviravada School, it is recorded that the monks were organised in groups specialising in each of the agamas or the Vinaya or the Abhidhamma, handing these texts down to their pupils and so maintaining the tradition.

In fact even ten years after his full 'entrance' into the community a monk was expected to know, besides part of the Vinaya discipline obligatory for all, only a part, usually about a third, of his agama, and these basic texts are pointed out in the commentary on the Vinaya.

A monk belonging to the Digha tradition, for example, should know ten of its long sutras, including the Mahaparinivana, the Mahanidana and the Mahasatipatthana.

He was then regarded as competent to teach. Among the Sthaviravadins there were even slight differences of opinion on certain matters between the several traditions of the sutras. Thus the Digha tradition did not admit the Avadanas to have been a text authenticated by recital at the First Rehearsal, whereas the Madhyama tradition did: they thus differed as to the extent of the Tipitaka.

If there were a standard Tipitaka as established at the First Rehearsal one might expect its texts to be fixed in their actual wording, and therefore in their language. This, however ' does not appear to have been the case.

The followers of the Buddha were drawn even during his lifetime from many different countries and spoke, if not completely different languages, at least different dialects.

It has been shown that the early Buddhists observed the principle of adopting the local languages wherever they taught. Probably they owe much of their success in spreading the Doctrine and establishing it in many countries to this.

The Buddha himself is recorded to have enjoined his followers to remember his teaching in their own languages, not in his language, nor in the archaic but respectable cadences of the Vedic scriptures of the Brahmans.

The recensions of the Tipitaka preserved in different countries of India therefore differed in dialect or language from the earliest times, and we cannot speak of any 'original' language of the Buddhist canon, nor, as it happens, have we any definite information as to what language the Buddha himself spoke.'

At the most, we can say that the recension in the language of Magadha may have enjoyed some pre-eminence for the first few centuries, since 'Magadhisms' have been detected even in non-Magahi Buddhist texts. This may have reflected the political supremacy of Magadha.

The British Library / University of Washington Early Buddhist Manuscripts Project was founded in September 1996 in order to promote the study, editing, and publication of a unique collection of fifty-seven fragments of Buddhist manuscripts on birch bark scrolls, written in the Kharosthi script and the Gandhari (Prakrit) language that were acquired by the British Library in 1994.

The manuscripts date from, most likely, the first century A.D., and as such are the oldest surviving Buddhist texts, which promise to provide unprecedented insights into the early history of Buddhism in north India and in central and east Asia.

Extract from an article by Dalya Alberge

The British Library has discovered remarkable manuscript fragments which it says may be as significant for Buddhist scholars as the Dead Sea Scrolls are for [[Wikipedia:Christianity|Christianity]] and Judaism. The manuscripts, birchbark scrolls that look like "badly rolled up cigars" when first shown to the library, are believed to be the earliest surviving Buddhist text. The exact origin is unknown beyond that they were probably found in Afghanistan in earthen jars.

"These will allow scholars to get nearer to what Buddha said than ever before,"the deputy director of the library's Oriental and Indian Office Collection, Mr Graham Shaw said. They date from the end of the first century AD or the beginning of the second century AD. Apart from bringing scholars closer to the original language of the Buddha, this could corroborate the authenticity of teachings recounted in later text.

The manuscripts include 60 fragments, ranging from the Buddha's sermons to poems and treatises on the psychology of perception. The library acquired them 18 months ago from a British dealer. "Their value was incalculable", Mr Shaw said.

" How would you put a value on the Dead Sea Scrolls?" It is believed they are part of the long-lost canon of the Sarvastivadin Sect that dominated Gandhara - modern north Pakistan and east Afghanistan - and was instrumental in Buddhism's spread into central and east Asia.

Gandhara was one of the greatest ancient centres of Buddhism.

Mr Shaw explained: "The scrolls tell us something about the way Buddhists passed on the teachings, which were for a long time passed on orally." After the Buddha's death, his disciples are said to have gathered in assemblies where they recited his sermons and organised them into what came to be the Buddhist canon.

Although nothing is known of their provenance, their attribution has been confirmed by the University of Seattle's Professor Richard Salomon, one of the world's greatest scholars of Kharosthi - a script derived from the Aramaic alphabet that was restricted to a small area of India.

They were, he said, "the Dead Sea Scrolls of Buddhism". Years of study lay ahead before the text can be deciphered, analysed and compared with existing texts.

The fragments include tales told on Lake Anavatapata's banks at an assembly of the Buddha and his disciples. Another is one of the Buddha's sermons on the rhinoceros horn (Suttanipata).

"The rhinoceros and its horn in particular is a symbol of non-attachment to material things ... it is not a herd animal. It just wanders alone."

The Pali Canon

The Pali Canon is the complete scripture collection of the Theravada school. As such, it is the only set of scriptures preserved in the language of its composition.

It is called the Tipitaka or "Three Baskets" because it includes the Vinaya Pitaka or "Basket of Discipline," the Sutta Pitaka or "Basket of Discourses," and the Abhidhamma Pitaka or "Basket of Higher Teachings".

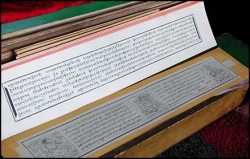

The Tibetan Canon

The Tibetan Canon which consists of two parts:

(1) the bKángjur ("Translation of the Word of the Buddha"), pronounced Kanjur, and

(2) the bStan-'gyur ("Translations of the Teachings") pronounced Tanjur.

Because this latter collection contains works attributed to individuals other than the Buddha, it is considered only semi-canonical.

The first printing of the Kanjur occurred not in Tibet, but in China (Beijing), being completed in 1411.

The first Tibetan edition of the canon was at sNar-tang with the Kanjur appearing in 1731, followed by the Tanjur in 1742.

Other famous editions of the canon were printed at Derge and Co-ne.

(a) bKángjur (Kanjur): Translation of the Word of the Buddha; 98 Volumes (according to the Narthang edition).

- Vinaya: 13 Volumes.

- Prajnaparamita: 21 Volumes.

- Avatamsaka: 6 Volumes.

- Ratnakuta: 6 Volumes.

- Sutra: 30 Volumes. 270 texts, 75% of which are Mahayana, 25% Hinayana (prominence and precedence being invariably given to Mahayana sutras).

- Tantra: 22 Volumes. Contains more than 300 texts.

The second, the Tanjur (bStan-'gyur) is a supplement to the former, or in other words, continuation of the tradition of the Kanjur.

Among its contents are a collection of stories, the commentaries on the Tantra section of the Kanjur and the commentaries on the sutra section.

There are also works relating to Abhidharma and Vinaya as well as Madhyamika and Vijnanavada.

Works coming under the sutra section of the Tanjur are not necessarily commentaries on the texts contained in the Mdo-section of the Kanjur.

They are believed to be authoritative works, some of which, however, are not even Buddhist in character.

They deal with logic, grammar, lexicography, poetry and drama, medicine and chemistry, astrology and divination, painting and biographies of saints.

Their inclusion in this part of the Tibetan Canon is perhaps justified on the acceptance of the position that they are necessary aids and accompaniments in the practice of the religion.

(b) bStan-'gyur (Tanjur): Translations of the Teachings 224 Volumes (3626 texts) according to the Beijing edition.

- A. Sutras ("Hymns of Praise"): 1 Volume; 64 texts.

- B. Commentaries on the Tantras: 86 Volumes; 3055 texts.

- C. Commentaries on Sutras; 137 Volumes; 567 texts.

- Prajnaparamita Commentaries, 16 Volumes.

- Madhyamika Treatises, 29 Volumes.

- Yogacara Treatises, 29 Volumes.

- Abhidharma, 8 Volumes.

- Miscellaneous Texts, 4 Volumes.

- Vinaya Commentaries, 16 Volumes.

- Tales and Dramas, 4 Volumes.

- Technical Treatises, 43 Volumes.

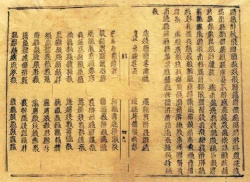

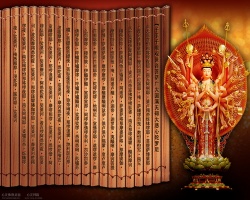

The Chinese Canon

The Chinese Canon is called the Ta-ts'ang-ching or "Great Scripture Store."

The first complete printing of the "Three Baskets" or Tripitaka was completed in 983 C.E., and known as the Shu-pen or Szechuan edition.

It included 1076 texts in 480 cases. A number of other editions of the modern Chinese Canon were made thereafter.

The now standard modern edition of this work is known as the Taisho Shinshu Daizokyo, published in Tokyo between 1924 and 1929.

It contains 55 volumes containing 2184 texts, along with a supplement of 45 additional volumes.

A fine chapter titled "The Chinese Tripitaka" can be found on pp. 365-368 of Buddhism in China (Princeton University Press), 1964 by Kenneth K.S. Ch'en.

The Chinese Tripitaka in World Buddhism

The main objective of the World Buddhist Fellowship is to link the various schools of Buddhism, coming as they do from all over the world.

This communion can be accomplished by harmonious cooperation on the basis of spiritual sharing.

As a global community we can then actualize the inspiring ideals of world enlightenment and salvation through the encouragement of our common Buddhist culture.

We must first acknowledge that the various schools of thought in Buddhism are indeed facets of the Triple Gem that is Buddhism.

There is no room for superficial and dogmatic claims that one school is true whereas others are not.

For instance the Mahayana schools should not be lightly dismissed as illegitimate, nor should the Sravakavana school conversely be despised as moribund.

Only when the study and practice of Buddhism is carried out in a friendly and accommodating atmosphere, with mutual trust and understanding, will coordination and cooperation be possible. With this attitude, the trash and trimmings now enshrouding Buddhism can be removed to reveal the essential splendour of the Triple Gem.

Thus Buddhism, which is well-adapted to this modern world, can be redeemed and developed for the purpose of the enlightenment and salvation of the world in its dire present need.

Buddhism stems from one point of origin and is highly adaptable under many circumstances.

For different races, time and environments, it seems to develop into entirely different shapes and forms. But a close study of its trends and modes of development, its adaptations to new environments whilst preserving the integral identity of its core, brings one to the realisation that the different forms of Buddhism are interrelated and that cooperation amongst them is entirely feasible.

Generally, each school has its own characteristics and shortcomings. Buddhists should honestly survey these various schools, exchanging the shortcomings in each for the strengths in others on the basis of equality, and for the sake of pursuing truth.

In so doing, the ultimate truth as experienced by the Buddha may be realized and his original intention, as embodied in his teaching, may be fully understood.

When we trace the different schools of Buddhism in the world today, from their origins in India, we can see that the profile sprouting of sectarian Buddhism seems to have taken place as follows:

(1) The sacred texts embodying the Buddha-dharma developed over time.

The sutras and Vinaya Pitaka were the earliest to be compiled and circulated.

Round about the beginning of the first century A.D., the researchers of the Agama Sutra and those dedicated to Sravaka practice had compiled the Abhidharma, emphasising the existential aspect of Dependent Origination.

On the other hand, the Mahayana scriptures had been compiled by those who stressed the virtues of the Buddha and the practice of the Bodhisattva, emphasizing the aspect of emptiness as central to the attainment of real understanding of Dependent Origination.

By the third century A.D., Nagarjuna had composed his famous Sastras on the Madhyamika doctrine interpreting the Agama and Abhidharma on the basis of the Mahayana sutras of the Sunyata school.

At about the same time, Mahayana scriptures tending towards 'eternal-reality' idealism, such as the Srimaladeve-Simhanada Sutra and the Mahaparinirvana Sutra, had begun to be found, followed by sutras such as the Lankavatara Sutra.

Along with this development, the Asters and Yogacaryas of the Sravastivada school accepted the "mind-only" aspect of the Mahayana school.

They compiled a number of Sastras of the Yogacara Vijnanavada and eventually flourished as a great Mahayana school in their own right.

Then, at about the fifth century there was a further development of esoteric Yoga from the school of eternal-reality idealism.

If one tried to follow the course of development of Buddhism as outlined above, one would have no difficulty tracing the evolution of the vast diversity of scriptures and doctrines held sacred by the many schools.

(2) Doctrinally, Buddhism was just Buddhism at first and there was no sectarian difference.

It did not divide into the Sravakayana and Bodhisattvayana until about the beginning of the Christian era.

Then in the scriptures of the Bodhisattvayana we begin to see the division of Hinayana and Mahayana.

In the second and third centuries scriptures of eternal-reality idealism started to appear in the Bodhisattvayana.

In such Sutras were first seen the terms "noumenon, Sunya and Madhya"; and "Hina-, Maha- and Eka-yana." T

These scriptures of later date laid special emphasis on the achievement of Buddhahood, and were thus also classified as Buddhayana.

At the beginning of the fifth century, another 'yana', the Dharaniyana, sprung into existence from the noumenal school of Buddhism.

This school classified all Buddha Dharma into the Tripitaka, the Paramita Pitaka (including everything of the exoteric schools), and the Dharani Pitaka.

It also categorised the Dharma according to practice as: Catvri-satyani, Paramita, and greed-ingrained.

These classifications are indicative of the diversification and development of Buddhism and are consistent with the schematic three periods of historical development proposed by the late Venerable Tai Hsu.

The latter were as follows:

- First 500 years after Buddha's demise - Hinayana in vogue with Mahayana in the background. The Pali Tipitaka are representative of the Buddhism of this period.

- Second 500 years - Mahayana to the fore with Hinayana attendant. The Chinese Tripitaka reflects the development of Buddhism in this period.

- Third 500 years - Tantric Buddhism took the lead, leaving the exoteric school in its wake. The Tibetan Tripitaka is the fruit of this period.

Chinese Buddhism - from which Japanese Buddhism derives is representative of the Buddhism of the second 500 years, i.e. it is founded mainly on Bodhisattvayana, which links the earlier Sravakayana and the later Buddhayana. It therefore effectively ties Buddhist history together.

As it plays such a pivotal role in the historical development of the Buddha-dharma, the Chinese Tripitaka deserves the special attention of all those concerned with the present development of world Buddhism. It is my humble opinion that only in the study of the Chinese Tripitaka can the contents of Buddhism be fully and totally understood. The Chinese Tripitaka offers the following:

(a) Agamas: All four Agamas belong to the Bhava division.

The Madhyamagama and Samyuktagama were translated from the texts of the Sravastivada school while the Dirghagama and Ekottaragama were translated from those of the Mahasamghika or Vibbajyavada schools.

Though admittedly it does not contain a complete set of the sutras of any single school, (the Pali Tripitaka does present a more complete set), a textual conglomeration of many schools does have its merits (The Tibetan Tripitaka contains no Agama at all).

(b) Vinayas: The Tibetan Tripitaka contains only the new rules of the Tamrasatiya sect, while the Chinese Vinaya contains all the following:

- (i) The Mahasamghika Vinaya of the Mahasamghika school.

- (ii) The five divisions of the Mahisasaka Vinaya, the four divisions of the Dharmagupta Vinaya, the pratimoksa of Mahadasyapiyah, and the Sudarsana Vinaya of Tamrasatiya. All these are rules of the Vibbajyavada school.

- (iii) The old Sravastivada Vinaya and the new Mulasarvasti vadanikaya Vinaya, both of the Sarvastivada school.

- (iv) The Twenty-Two-Points-Of-Elucidation Sastras of the Sammatiya sect of the Vatsiputriyas school.

This rich collection of materials from different sources greatly facilitates comparative studies of sectarian Buddhism.

(c) Abhidharmas: This body of scripture is common to the three main schools of Theravada Buddhism, namely, the Vibhajyavadins, the Sarvastivadins, and the Vatsiputriyas. In the Tibetan Tripitaka there are only the Prajnapti of the Jnanaaprasthanasatpadabhidharma and the later Abhidarmakosa.

The Pali Tripitaka contains seven Sastras. While the Chinese Tripitaka has an especially large collection of the work of the Sarvastivada school, it also possesses the Abhidharma work of practically all sects. The Chinese Tripitaka contains:

- i) The Samgitiparyaya, the Dharmaskandha, the Prajnapti, the Vijnanakaya, the Dhatukaya, the Prakaranapada, the Jnanaprasthana, the Mahavibhasa, the Abhidharma-hrdaya-vyakhya, the Abhiraharmananyanyanusara and the Abhidharmasamayapradipika Sastras of the Sarvastivada school.

- ii) Of the works of Vibhajyavadins, it includes the Abhidharma Sastra of Sariputa, which is the only important work that links up the Southern and Northern Abhidharmas.

- iii) It also contains the Vimmuttimagga which is a different version of the Pali Visuddhimagga.

- iv) It further contains the Sammitiya Sastra of the Vatsiputriya School.

- v) The renowned Abhidharmakosa of the third to fourth century which combines the best teachings of the Sarvastivada and Sautrantika schools, and the Satyasiddi Sastra of Harivarman which greatly influenced Chinese Buddhism.

All these treasures of the Abhidharma may be found in the Chinese Tripitaka.

It can thus be seen that although the works of earlier dates in the Tripitaka were not given the full respect due them by the majority of Chinese Buddhists, the wealth of information they contain will be of great reference value to anyone interested in tracing the divisions of the Sravaka schools and the development of the Bodhisattva ideal from the Sravakayana.

If these scriptures are ignored, I will say that it would definitely not be possible for anyone to fulfil the responsibility of coordinating and linking the many branches of world Buddhism.

(d) Mahayana scriptures of the Sunyavada.

(e) Mahayana scriptures of the noumenon school, or the school of eternal-reality, are very complete in the Chinese Tripitaka.

These scriptures are very similar to those found in the Tibetan Tripitaka.

The four great Sutras, the Prajnaparamita, the Avatamsaka, the Mahasamghata, and the Mahaparinirvana (to which may be added the Maharatnakuta Sutra, making five great sutras), are all tremendously voluminous works.

Here it may be pointed out that the Chinese scriptures are particularly notable for the following characteristics:

- (i) The different translations of the same Sutra have been safely preserved in the Chinese Tripitaka in their respective original versions without their being constantly revised according to later translations, as was the case with Tibetan scriptures.

From a study of the Chinese translations we can thus trace the changes in content which the majority of scriptures have undergone over time and reflect upon the changes in the original Indian texts at different points in time. Thus we have the benefit of more than one version for reference, recording the evolution of the scriptures.

- (ii) The Chinese Mahayana scriptures that were translated before the Tsin Dynasties (beginning 265 C.E.) are particularly related to the Buddhism of Chinese Turkestan with its centre in the mountain areas of Kashmir.

These scriptures form a strong nucleus of Chinese Buddhist thinking. The translations of the Dasabhumika Sastra and Lankavatara Sutra all possess very special characteristics.

(f) Madhyamika: The Madhyamika texts of the Chinese Tripitaka are considerably different from the Tibetan renditions of the same system of thought.

The Chinese collection consists mostly of earlier works, particularly those of Nagarjuna, such as the Mahaprajnaparamita Sastra and the Dasabhumikavibhasa Sastra, which not only present Madhyamika philosophy of a very high order but also illustrate extensively the acts of a Bodhisattva.

Of the late Madhyamika works, i.e. works produced by the disciples of Nagarjuna after the rise of the Yogacara system, only the Prajnapradipa Sastra of Bhavaviveka has been rendered into Chinese.

The Chinese Tripitaka does not contain works or as many schools of this system as the Tibetan Tripitaka.

The Mahayanavataraka Sastra of Saramati and the Madhyayata Sastra of Asanga clearly indicate the change of thinking from the Madhyamika to the Yogacara system.

(g) Yogacara-Vijnanavada: The Chinese Tripitaka contains a very complete collection of this system of thought.

It includes important scriptures such as the Dasabhumika, Mahayanasamparigraha Sastra, and Vijnaptimatrasiddhi Sastra.

While the Tibetan system was mainly founded on the teachings of Sthiramati which are more akin to the Mahayanasamparigraha school of Chinese work, the Chinese students of orthodox Vijnanavada follow the teachings of Dharmapala.

The Vinaptimatrasiddhi Sastra, which represents the consummation of the Dignaga-Dharmapala-Silabhadra school of thought, is a gem of the Chinese Tripitaka.

The Hetuvidya which is closely connected with Vijnanavada, is not fully translated in the Chinese Tripitaka and cannot compare favourably with the works of Dignaga and Dharmakirti collected in the Tibetan Tripitaka.

This seems to indicate that the Chinese people were not logically inclined, and gives no weight to engagements in verbal gymnastics and debates. In times past this had relegated the position of Sastra masters in China to one of relative unimportance.

(h) The esoteric Yoga: The Chinese Tripitaka includes Chinese translations of both the Vairocana Sutra of the practical division, and the Diamond Crown Sutra of the Yoga division of the Tantric school of Buddhism.

The only esoteric scriptures that are missing are those of the Supreme Yoga division which, as they arrived in China at a time of national chaos, did not have much chance to circulate widely.

Its very nature of achieving enlightenment through carnal expressions also made Tantrism unacceptable to the Chinese intellectuals.

However, the texts of esoteric Yoga are abundant in the Tibetan Tripitaka.

From the above it can be seen that the Chinese Tripitaka is composed mainly of Mahayana scriptures of the second 500 years, yet translations were not restricted to scriptures of this middle period.

The Chinese Tripitaka also possesses a wealth of works of early Buddhism as a good portion of the later productions.

Thus, if one could have a sufficient knowledge of the Chinese Tripitaka, and could extend his knowledge from there to include the Pali Tripitaka of the Sravakayana, and the Madhyamika and Supreme Yoga of the Tibetan system, then he would have little difficulty in gaining an accurate, complete and comprehensive panorama of the 1,700 years of development of Indian Buddhism, the record of which has been preserved in the three great extant schools of Buddhist thought.

The late Venerable Tai Hsu once said, "To mold a new, critical and comprehensive system, based on the Chinese Tripitaka, the Theravada teaching of Ceylon, and selected components of the Tibetan canon, should be the objective of the writing of a history of Indian Buddhism."

Even more so, it should be the objective of coordinating and connecting the many tributaries of world Buddhism.

It is our responsibility to discard the trimmings and to retain the very essence of the great Tripitakas, adapting Buddhism to the modern world so that it may fulfil its mission of leading the way, taking under its wings the miserable beings of the present era.

Translated by Mok Chung, edited by Mick Kiddle, proofread by Neng Rong. (20-6-1995)

Guide to Mahayana Sutras

Other Names

|

Notes

| |

| Shorter Amitabha Sutra. |

One of the three sutras that form the doctrinal basis of the Pureland School - the two others are Meditation Sutra and Longer Amitabha Sutra. It describes the Blessings and Virtues of Amitabha Buddha and his Pureland, and discusses rebirth. | |

| Flower Ornament Sutra. Flower Garland Sutra. |

Second longest sutra in the Mahayana Canon, (40 chapters). It consists of large important, independent sutras, namely: Gandavyuha Sutra, Dashabhumika Sutra, Amitayurdyhana Sutra. It records the higher teaching of the Buddha to Bodhisattvas and other high spiritual beings. | |

Brahma Net

|

Brahmajala Sutra. | This contains the Ten Major Precepts of Mahayana followers, and the Bodhisattva Precepts. |

| Vajracchedika Prajnaparamita Sutra. | One of the two most famous scriptures in the Prajnaparamita group of sutras (the other is the Heart Sutra). The Diamond Sutra sets forth the doctrines of Sunyata (emptiness) and Prajna (wisdom). | |

| Prajnaparamita-Hrdaya Sutra. | One of the smallest sutras, and with the Diamond Sutra, one of the most popular of the 40 sutras, in the vast Prajnaparamita literature. Its emphasis is on emptiness. | |

Heroic Gate

|

Surangama Sutra. | Emphasises the power of Samadhi (meditation) and explains various methods of emptiness meditation. A key text of the Ch'an and Zen traditions. |

Jewel Heap

|

Ratnakuta Sutra. | One of the oldest sutras, which belongs to the Vaipulya group of 49 independent sutras. Summary: The philosophy of the middle is developed, which later becomes the basis for the Madhyamaka teaching of Najarjuna. It contains sutras on transcendental wisdom (Prajnaparamita Sutra) and the Longer Amitabha Sutra. |

| A scriptural basis of the Yogacara and Zen Schools. It teaches subjective idealism based on the Buddha's enlightenment, and doctrines of emptiness and mind only. | ||

Longer Amitabha

|

Larger Amitabha Sutra. |

One of the three core Pueland texts. It explains cause and effect, and describes the Pureland. |

| Saddharma Pundarika Sutra. Lotus of the Good Law. |

A major text, of which the Tendai (T'ien T'ai) use as a main scripture. It teaches the identification of the historical Buddha, with the Transcendental Buddha. | |

| Amitayurdyhana Sutra. | One of the three core texts of the Pureland school. It teaches meditation and visualisation. | |

| Dasabhumika Sutra. Sutra on the Ten Stages. |

This sutra is the 26th chapter of Avatamsaka Sutra, and is also an independent sutra. It establishes the ten stages of cultivation that the Bodhisattva must traverse on the path to enlightenment. | |

| This is a philosophic dramatic discourse, in which basic Mahayana principles are presented in the form of a conversation between famous Buddhist figures, and the householder, Vimalakirti. |