The Rewards of the Contemplative Life

There is the case where a Tathagata appears in the World, worthy and rightly self-awakened. He teaches the Dhamma admirable in its beginning, admirable in its middle, admirable in its end. He proclaims the holy Life both in its particulars and in its essence, entirely perfect, surpassingly pure.

A Householder or Householder's son, hearing the Dhamma, gains conviction in the Tathagata and reflects: 'Household life is confining, a dusty path. The Life gone forth is like the open air. It is not easy living at home to practice the holy Life totally perfect, totally pure, like a polished shell. Suppose I were to go forth?'

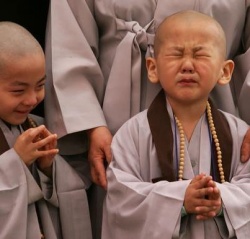

So after some time he abandons his mass of Wealth, large or small; leaves his circle of relatives, large or small; shaves off his Hair and beard, puts on the saffron robes, and goes forth from the Household life into homelessness.

When he has thus gone forth, he lives restrained by the rules of the monastic code, seeing danger in the slightest faults. Consummate in his Virtue, he guards the doors of his senses, is possessed of Mindfulness and presence of mind, and is content...

Now, how does a Monk guard the doors of his senses? On seeing a Form with the eye, he does not grasp at any theme or variations by which — if he were to dwell without restraint over the faculty of the eye — Evil, unskillful qualities such as Greed or distress might assail him. (Similarly with the ear, nose, tongue, Body, and intellect.)

And how is a Monk possessed of Mindfulness and alertness? When going forward and returning, he acts with alertness. When looking toward and looking away... when bending and extending his limbs... when carrying his outer cloak, his upper robe, and his bowl... when eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting... when urinating and defecating... when walking, standing, sitting, falling asleep, waking up, talking, and remaining silent, he acts with alertness.

And how is a Monk content? Just as a bird, wherever it goes, flies with its wings as its only burden; so too is he content with a set of robes to provide for his Body and alms Food to provide for his hunger. Wherever he goes, he takes only his barest necessities along.

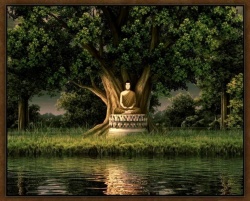

He seeks out a secluded dwelling: a forest, the shade of a tree, a mountain, a glen, a hillside cave, a Charnel ground, a jungle grove, the open air, a heap of straw. After his meal, returning from his alms round, he sits down, crosses his legs, holds his Body erect, and brings Mindfulness to the fore. He purifies his mind from Greed, ill will, sloth and torpor, restlessness and anxiety, and uncertainty. As long as these five hindrances are not abandoned within him, he regards it as a debt, a sickness, a prison, slavery, a road through desolate country. But when these five hindrances are abandoned within him, he regards it as unindebtedness, good health, release from prison, freedom, a place of security. Seeing that they have been abandoned within him, he becomes glad, enraptured, tranquil, sensitive to pleasure. Feeling pleasure, his mind becomes concentrated.

Quite withdrawn from sensuality, withdrawn from unskillful mental qualities, he enters and remains in the first Jhana: rapture and pleasure born from withdrawal, accompanied by directed thought and evaluation. He permeates and pervades, suffuses and fills this very Body with the rapture and pleasure born from withdrawal. Just as if a skilled bathman or bathman's apprentice would pour bath powder into a brass basin and knead it together, sprinkling it again and again with water, so that his ball of bath powder — saturated, moisture-laden, permeated within and without — would nevertheless not drip; even so, the Monk permeates... this very Body with the rapture and pleasure born of withdrawal. There is nothing of his entire Body unpervaded by rapture and pleasure born from withdrawal. This is a reward of the contemplative Life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

Furthermore, with the stilling of directed thoughts & evaluations, he enters and remains in the second Jhana: rapture and pleasure born of composure, unification of awareness free from directed thought and evaluation — internal assurance. He permeates and pervades, suffuses and fills this very Body with the rapture and pleasure born of composure. Just like a lake with spring-water welling up from within, having no inflow from the east, west, north, or south, and with the skies supplying abundant showers time and again, so that the cool fount of water welling up from within the lake would permeate and pervade, suffuse and fill it with cool waters, there being no part of the lake unpervaded by the cool waters; even so, the Monk permeates... this very Body with the rapture and pleasure born of composure. There is nothing of his entire Body unpervaded by rapture and pleasure born of composure. This, too, is a reward of the contemplative Life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

And furthermore, with the fading of rapture, he remains equanimous, mindful, & alert, and senses pleasure with the Body. He enters & remains in the third Jhana, of which the Noble Ones declare, 'Equanimous & mindful, he has a pleasant abiding.' He permeates and pervades, suffuses and fills this very Body with the pleasure divested of rapture. Just as in a Lotus pond, some of the lotuses, born and growing in the water, stay immersed in the water and flourish without standing up out of the water, so that they are permeated and pervaded, suffused and filled with cool water from their roots to their tips, and nothing of those lotuses would be unpervaded with cool water; even so, the Monk permeates... this very Body with the pleasure divested of rapture. There is nothing of his entire Body unpervaded with pleasure divested of rapture. This, too, is a reward of the contemplative Life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime.

And furthermore, with the abandoning of pleasure and stress — as with the earlier disappearance of elation and distress — he enters and remains in the fourth Jhana: purity of Equanimity and Mindfulness, neither-pleasure nor stress. He sits, permeating the Body with a pure, bright awareness. Just as if a man were sitting covered from head to foot with a white cloth so that there would be no part of his Body to which the white cloth did not extend; even so, the Monk sits, permeating the Body with a pure, bright awareness. There is nothing of his entire Body unpervaded by pure, bright awareness. This, too, is a reward of the contemplative Life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime...

With his mind thus concentrated, purified, and bright, he directs it to the Knowledge of the ending of the mental fermentation. Just as if there were a pool of water in a mountain glen — clear, limpid, and unsullied — where a man with good eyesight standing on the bank could see shells, gravel, and pebbles, and also shoals of fish swimming about and resting, and it would occur to him, 'This pool of water is clear, limpid, and unsullied. Here are these shells, gravel, and pebbles, and also these shoals of fish swimming about and resting.' In the same way, the Monk discerns, as it has come to be, that 'This is stress... This is the origination of stress... This is the cessation of stress... This is the way leading to the cessation of stress... These are mental fermentations... This is the origination of fermentations... This is the cessation of fermentations... This is the way leading to the cessation of fermentations.' His Heart, thus knowing, thus seeing, is released from the fermentations of sensuality, becoming, and Ignorance. With release, there is the Knowledge, 'Released.' He discerns that 'Birth is ended, the holy Life fulfilled, the task done. There is nothing further for this World.' This, too, is a reward of the contemplative Life, visible here and now, more excellent than the previous ones and more sublime. And as for another visible fruit of the contemplative Life, higher and more sublime than this, there is none.