The Word Tantrism

The word Tantrism has become an accepted term in the English language, but apart from this fact there is little evidence that any serious attempt has been made to clarify what this word implies and what that for which it stands means to the individual who becomes involved with the discipline of Tantrism. Generalizations about Tantrism are, as a rule, misleading because they rest on an insufficient factual basis. Before we can generalize we must know something

of the underlying premises which have been guiding the development of Tantrism through the ages. In this book I have endeavoured to deal with these premises on the basis of indigenous Tibetan texts, rather than with individual Sanskrit works and their translations (although they, too, have been utilized) because the indigenous Tibetan texts go to the very root of Tantrism. The limitation of this approach is that I deal with Buddhist, not Hinduist, Tantrism; the advantage of this approach is that I avoid confusing ideas that have nothing to do with each other.

It is my conviction that Tantrism in its Buddhist form is of the utmost importance for the inner life of man and so for the future of mankind. If the life of the spirit is to be invigorated, there must be a new vision and understanding, and there is hardly anything of such value as the study of the experiences and

the teaching of the Buddhist Tantrics. For Tantrism is founded on practice and on an intimate personal experience of reality, of which traditional religions and philosophies have given merely an emotional or intellectual description, and for Tantrism reality is the everpresent task of man to be,

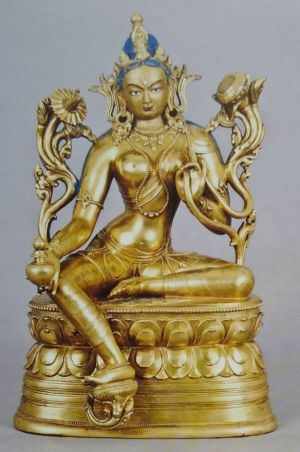

The critical references to Western ideas, assumptions, and conclusions are not meant as a disparagement, but as a means to PREFACE highlight the contrast between two divergent conceptual frameworks, the one, predominantly mechanical and theistically nomothetic; the other, basically dynamic and existentially appreciative. Unless these points of divergence are made clear only a mystificatory hotchpotch and a cheap sentimentalism result. I am greatly indebted to the Government of India, Archaeological Survey, for making available photographs of relevant sculptures.

Being — The Quintessence of Tantra: An Outline The concrete presence of Being is twofold :

The presence of the body means that It is knowable in a gradation of coarse, Subtle, and very subtle, generally indivisible.

From the radiant light (comes) a great blankness, From this both enactment and appreciation come in a plurality (of life-forms) (Which in turn is) five awakenings, Structure, motility, and bodhicitta (life's energy).

(The Ground)

The concrete presence of mind means

That it resides in the center of the body as E-VAM, Being of the nature of enactment and appreciation. This is the fundamental awareness present in the body, It is the abolition of all fictions.

(The way)

Free from the concepts of mandala and of [[Karmamudra] and Jñãnamudra,

Do not negate, do not suspend (the mental working), do not find fault, Do not fix (the min d on something), do not evaluate, but just let be. (The Goal) As the seed, so the tree— As the tree, so the fruit. Looking at the whole world in this way— This then is relativity.

From Rhapramamasamyak-nama-dakini-upadeýa

The Significance of Tantra

HEN in 1799 the word Tantra was introduced into the English language, it was used with reference to a certain kind of literature that in many ways has remained baffling to those who have tried to fit it into the general, highly idealized and therefore utterly misleading, picture of Indian philosophies, which were assumed to be of one piece. Since the word Tantra occurred in both Hinduist and Buddhist book titles, these writings were first lumped together and then

dismissed as inadmissive of 'clear' statements. The alleged obscurantism of this literature, however, was but a reflection of the shocking parochialism of those who had access to it and who assumed that what was not of Western origin consisted merely of a welter of myths and poetry, religion and superstition, and

hence was negligible and contemptible. Moreover, since this literature included topics which were excluded from the 'respectable' domain of 'philosophy', assumed to be a repository of deep, clear and high ideals with little bearing on the harsh realities of actual life except in so far as it concealed them, a curious ambivalence resulted. Either the literature was said to reflect a sad state of intellectual and moral degeneration, or it was believed to contain the

keys to a world of power and sex, the two basic notions that haunt all those who are lacking in the one or the other and especially those lacking in both. Although the degeneration theory has been largely abandoned, the assumption that power and sex are the primary concern of Tantrism is still widespread, for it is easier, and possibly more lucrative, to perpetuate ignorance than to gain and disseminate knowledge. The fact that in the Western world the word Tantra is almost exclusively used with reference to a TANTRIC VIEW LIFE power- and sex-inflated esoteric teaching and not at all in its broader connotation of 'expanded treatise', is highly illuminating as far as Western thinking is concerned, but it does not throw any light on what Tantra means in itself.

The word Tantra is used differently, and hence does mean different things to Hindus and Buddhists. This is also borne out by the underlying metaphysics so that Buddhist and Hinduist Tantrism are quite distinct from each other, and any similarities are purely accidental, not at all essential. Hinduist Tantrism, due to its association with the Sãmkhya system, reflects a psychology of subjectivistic dominance, but tempers it by infusing the human with the divine and vice versa; Buddhist Tantrism aims at developing man's

cognitive capacities so that he may be, here and now, and may enact the harmony of sensuousness and spirituality. Dominance or power has a strong appeal to the ego, as it enables the ego to think that it is the master of its world. Dominance also strikes a resonant chord in us who live in a mass society that threatens to annihilate the individual. Again it is power that seems to compensate for the inner feeling of despair. But unaware of the fact that the acceptance of power as the supreme value is the surrender of one's true individuality, a person who feels insecure

and is afraid of becoming himself may turn to anything that seems to promise him the attainment of power. Because of this slanted view and because the word fakti 'creative energy', frequently used in Hinduist Tantra, but never in Buddhist Tantra, could be understood as 'power', the word Tantrism has almost exclusively become synonymous with Hinduist 'Tantra', and more is known about it than about Buddhist 'Tantra' which stresses individual growth and tries to realize the uniqueness of being human.

In Buddhism, Tantra means both 'integration' and 'continuity', as is stated in the Guhyasamajatantra " 'Tantra' is continuity, and this is threefold: Ground, Actuality, and Inalienableness.'

Tantrism begins with the concrete human situation of man's lived existence, and it tries to clarify the values that are already implicit in it. Its gaze is not primarily directed towards an exSIGNIFICANCE TANTRA ternal system which is passively received by observation and then dealt with as an object of some kind; nor does Tantrism speculate about a transcendental subject beyond the finite person. Rather it attempts to study the finite existence of man as lived from within,

without succumbing to another kind of subjectivism. Man's existence as it is lived in the concrete is quite distinct from the limited horizons of more 'objective' reason and science which have their distinct values but are not the only values; and it is known in a different way. The world of man is not some solipsism (subjectivism at its peak) nor is it the sum total of all the objects that can be found in the world; the world of man is his horizon of meaning without which there can neither be a world nor an understanding of it so that man can live. This horizon of meaning is not something fixed once and for ever,

but it expands as man grows, and growth is the actuality of man's lived existence. Meanings do not constitute another world, but provide another dimension to the one world which is the locus of our actions. In this way, Being is not some mysterious entity, it is the very beginning and the very way of acting and the very goal. It is both the antecedents of our ideas and what we do with them for the enrichment of our lives. The emphasis Buddhism places on knowledge (ye-shes, jñãna) and on discriminative-appreciative awareness (shes-rab, prajñã) is the outcome of the realization that the human problem is one of knowledge and

that knowledge is not merely a record of the past but a reshaping of the present directed towards fulfilments in the emerging future. This, then, is the meaning of Tantra as 'continuity'. Its triple aspect, as outlined in the aphorism from the Guhyasamãjatantra, is explained by Padma dkar-po as follows : "The actuality or actual presence of all that is, ranging from colour-form to the intrinsic awareness of all observable qualities, is called 'concrete existential presence'. Since this is unalterably present, like the sky, (in everything) beginning with sentient beings and ending with Buddhas, it is termed 'Tantra as actuality' because of its continuousness.

"It is a way because it has to be travelled by (means of our) actions which mature and become pure in this unsullied Being, and it is a gradation because it continuously TANTRIC VIEW LIFE proceeds from the level of the accumulation of knowledge and merits to the level of a Sceptre-holder. Hence it is called a 'gradation of the way'.a

"Since it is the ground from which all virtues grow and in which they stay, it is called 'Tantra as ground', and it is called 'Tantra as action' because it is the concomitant condition for becoming enlightened.'

"Goal is the attainment of the state of a Sceptre-holder who is the source of 'being-for-others', characterized by being free from incidental blemishes, and since (the process of) becoming enlightened continues as long as there are sentient beings as inexhaustible as the sky, there is gradual emergence (of fulfilment) and this gradual emergence of the goal is called 'Tantra as Goal'. Since this is characterized as an overturning of the obstacles set up by experientially initiated potentialities of experience, and as not incurring the loss of 'being-for-others' as in the case with a Nirvana, in which awareness ceases, it is 'Tantra as Inalienableness .

There is thus no escape from Being, and what Tantra is telling us is that we have to face up to Being; to find meaning in life is to become Buddha—'enlightened', but what this meaning is cannot be said without falsifying it. Therefore, also, the knowledge on which Tantrism insists is not knowledge of this or that, of nature, society, or of the self, but the knowledge that makes all these kinds of knowledge possible. Similarly, the action it advocates is not

an action which fits a person effectively into the context of a preconceived scheme but an action which is selfdisciplinary and responsible. Responsibility is not merely action, rather it is a view of the one real world from another perspective, which as the goal is the realization of what we have been all along, because it is no less Being than the ground or starting-point. The passage from the hidden presence of the existential values to their existence is openly recognized.

It is in tune with the practical nature of Tantrism that it is centred on man, though not in the sense that 'man is everything', which is to depersonalize and to depreciate him as much as to

SIGNIFICANCE TANTRA subordinate him to a transcendental deity. The problem is not man's essence or nature, but what man can make of his life in this world so as to realize the supreme values that life affords. If there is any principle that dominates Tantric thought, it is so thoroughly a reality principle that nothing of subjectivism in contrast to an 'objective' reality remains. In the pursuit of Being there is a joyousness and directness which appears elsewhere to be found only in Zen, that is, the culmination of Sino-Japanese Buddhism, not the dilettantism of the retarded adolescents of the xvvest, which in certain quarters at least is already on the way out. By way of comparison, Tantrism can be said to be the culmination of Indo-Tibetan Buddhism.