Vipassana-bhāvanā

Vipassanā-bhāvanā

Vipassanā is often described as being a flash of insight, a sudden intuition of truth. The description is correct, but in fact there is a step-by-step method which meditators can use to advance to the point that they are capable of such intuition. This method is Vipassanā-bhāvanā, the development of insight, commonly called Vipassana meditation.

The word passanā means "seeing," the ordinary sort of vision that we have with open eyes. Vipassanā means a special kind of vision: observation of the reality within oneself. This is achieved by taking as the object of attention ones own physical sensations. The technique is the systematic and dispassionate observation of sensations within oneself. This observation unfolds the entire reality of mind and body.

Why sensation? First because it is by sensations that we experience reality directly. Unless something comes into contact with the five physical senses or the mind, it does not exist for us. These are the gates through which we encounter the world, the bases for all experience. And whenever anything comes into contact with the six sensory bases, a sensation occurs. The Buddha described the process as follows: "If someone takes two sticks and rubs one against the other, then from the friction heat is generated, a spark is produced. In the same way, as the result of a contact to be experienced as pleasant, a pleasant sensation arises. As the result of a contact to be experienced as unpleasant, an unpleasant sensation arises. As the result of a contact to be experienced as neutral, a neutral sensation arises."

The contact of an object with mind or body produces a spark of sensation. Thus sensation is the link through which we experience the world with all its phenomena, physical and mental. In order to develop experiential wisdom, we must become aware of what we actually experience; that is, we must develop awareness of sensations.

Further, physical sensations are closely related to the mind, and like the breath they offer a reflection of the present mental state. When mental objects—thoughts, ideas, imaginations, emotions, memories, hopes, fears—come into contact with the mind, sensations arise. Every thought, every emotion, every mental action is accompanied by a corresponding sensation within the body. Therefore by observing the physical sensations, we also observe the mind.

Sensation is indispensable in order to explore truth to the depths. Whatever we encounter in the world will evoke a sensation within the body. Sensation is the crossroads where mind and body meet. Although physical in nature, it is also one of the four mental processes . It arises within the body and is felt by the mind. In a dead body or inanimate matter, there can be no sensation, because mind is not present. If we are unaware of this experience, our investigation of reality remains incomplete and superficial. Just as to rid a garden of weeds one must be aware of the hidden roots and their vital function, similarly we must be aware of sensations, most of which usually remain hidden to us, if we are to understand our nature and deal with it properly.

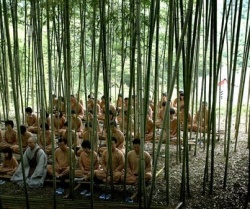

Sensations occur at all times throughout the body. Every contact, mental or physical, produces a sensation. Every biochemical reaction gives rise to sensation. In ordinary life, the conscious mind lacks the focus necessary to be aware of all but the most intense of them, but once we have sharpened the mind by the practice of ānāpāna-sari and thus developed the faculty of awareness, we become capable of experiencing consciously the reality of every sensation within.

In the practice of awareness of respiration the effort is to observe natural breathing, without controlling or regulating it. Similarly, in the practice of vipassanā-bhāvanā, we simply observe bodily sensations. We move attention systematically throughout the physical structure from head to feet and feet to head, from one extremity to the other. But while doing so we do not search for a particular type of sensation, nor try to avoid sensations of another type. The effort is only to observe objectively, to be aware of whatever sensations manifest themselves throughout the body. They may be of any type: heat, cold, heaviness, lightness, itching, throbbing, contraction, expansion, pressure, pain, tingling, pulsation, vibration, or anything else. The meditator does not search for anything extraordinary but tries merely to observe ordinary physical sensations as they naturally occur.

Nor is any effort made to discover the cause of a sensation. It may arise from atmospheric conditions, because of the posture in which one sits, because of the effects of an old disease or weakness in the body, or even because of the food one has eaten. The reason is unimportant and beyond one's concern. The important thing is to be aware of the sensation that occurs at this moment in the part of the body where the attention is focused.

When we first begin this practice, we may be able to perceive sensations in some parts of the body and not in others. The faculty of awareness is not yet fully developed, so we only experience the intense sensations and not the finer, subtler ones. However, we continue giving attention to every part of the body in tum, moving the focus of awareness in systematic order, without allowing the attention to be drawn unduly by the more prominent sensations. Having practised the training of concentration, we have developed the ability to fix the attention on an object of conscious choosing. Now we use this ability to move awareness to every part of the body in an orderly progression, neither jumping past a part where sensation is unclear to another part where it is prominent, nor lingering over some sensations, nor trying to avoid others. In this way, we gradually reach the point where we can experience sensations in every part of the body.

When one begins the practice of awareness of respiration, the breathing often will be rather heavy and irregular. Than it gradually calms and becomes progressively lighter, finer, subtler. Similarly, when beginning the practice of vipassanā-bhāvanā, one often experiences gross, intense, unpleasant sensations that seem to last for a long time. At the same time, strong emotions or long-forgotten thoughts and memories may arise, bringing with them mental or physical discomfort, even pain. The hindrances of craving, aversion, sluggishness, agitation, and doubt which impeded one's progress during the practice of awareness of breathing may now reappear and gain such strength that it is altogether impossible to maintain the awareness of sensation Faced with this situation one has no alternative but to revert to the practice of awareness of respiration in order once again to calm and sharpen the mind.

Patiently, without any feeling of defeat, as meditators we work to re-establish concentration, understanding that all these difficulties are actually the results of our initial success. Some deeply buried conditioning has been stirred up and has started to appear at the conscious level. Gradually, with sustained effort but without any tension, the mind regains tranquility and one-pointedness.