Bodhisattva

Click here to see other articles relating to word Bodhisattva

In Buddhism, a bodhisattva (Sanskrit: बोधिसत्त्व bodhisattva; Pali: बोधिसत्त Bodhisatta) is either an Enlightened (Bodhi) existence (sattva) or an Enlightenment-being or, given the variant Sanskrit spelling satva rather than sattva, "heroic-minded one (satva) for Enlightenment (Bodhi)."

The Pali term has sometimes been translated as "Wisdom-being," although in modern publications, and especially in tantric works, this is more commonly reserved for the term jñānasattva ("awareness-being"; Tib. ཡེ་ཤེས་སེམས་དཔའ་, Wyl. ye shes sems dpa’).

Traditionally, a bodhisattva is anyone who, motivated by great Compassion, has generated Bodhicitta, which is a spontaneous wish to attain Buddhahood for the benefit of all Sentient beings.

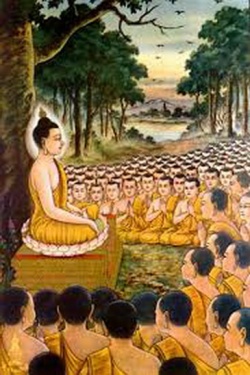

The bodhisattva is a popular subject in Buddhist Art.

Usage of the term bodhisattva has evolved over time. In early Indian Buddhism, for example, the term bodhisattva was primarily used to refer specifically to the Buddha Shakyamuni in his former lives.

The Jatakas, which are the stories of his lives, depict the various attempts of the bodhisattva to embrace qualities like self-sacrifice and Morality.

In Theravāda Buddhism

The term "Bodhisatta" (Pāli Language) was used by The Buddha in the Pāli Canon to refer to himself both in his previous lives and as a young man in his current Life, prior to his Enlightenment, in the period during which he was working towards his own Liberation.

When, during his discourses, he recounts his experiences as a young aspirant, he regularly uses the phrase "When I was an unenlightened Bodhisatta..."

The term therefore connotes a being who is "bound for Enlightenment", in other words, a person whose aim is to become fully Enlightened.

In the Pāli Canon, the Bodhisatta is also described as someone who is still subject to birth, illness, Death, sorrow, defilement, and Delusion. Some of the previous lives of The Buddha as a bodhisattva are featured in the Jātaka tales.

In the Pāli Canon, the Bodhisatta Siddhartha Gotama is described thus:

- before my Awakening, when I was an unawakened Bodhisatta, being subject myself to birth, sought what was likewise subject to birth. Being subject myself to aging... illness... Death... sorrow... defilement, I sought (happiness in] what was likewise subject to illness... Death... sorrow... defilement.

While Maitreya (Pāli: Metteya) is mentioned in the Pāli Canon, he is not referred to as a bodhisattva, but simply the next fully Awakened Buddha to come into existence long after the current teachings of The Buddha are lost.

In later Theravāda literature, the term "Bodhisatta" is used fairly frequently in the sense of someone on the path to Liberation.

The later tradition of commentary also recognizes the existence of two additional types of bodhisattas:

the paccekabodhisatta who will attain Paccekabuddhahood, and the savakabodhisatta who will attain Enlightenment as a Disciple of a Buddha. According to the Theravāda teacher Bhikkhu Bodhi the bodhisattva path was not taught by Buddha .

Theravadin Bhikku and scholar Walpola Rahula Sri Rahula Maha Thera) has stated that the Bodhisattva ideal has traditionally been held to be higher than the state of a śrāvaka not only in Mahāyāna, but also in Theravāda Buddhism.

He also quotes an inscription from the 10th Century king of Sri Lanka, Mahinda IV (956-972 CE) who had the words inscribed "none but the Bodhisattvas would become kings of Sri Lanka", among other examples.

- There is a wide-spread belief, particularly in the West, that the ideal of the Theravada, which they conveniently identify with Hinayana, is to become an Arahant while that of the Mahayana is to become a Bodhisattva and finally to attain the state of a Buddha.

It must be categorically stated that this is incorrect.

This idea was spread by some early Orientalists at a time when Buddhist studies were beginning in the West, and the others who followed them accepted it without taking the trouble to go into the problem by examining the texts and living traditions in Buddhist countries.

But the fact is that both the Theravada and the Mahayana unanimously accept the Bodhisattva ideal as the highest.

Paul Williams writes that some modern Theravada Meditation masters in Thailand are popularly regarded as Bodhisattvas.

- Cholvijarn observes that prominent figures associated with the Self perspective in Thailand have often been famous outside scholarly circles as well, among the wider populace, as Buddhist Meditation masters and sources of miracles and sacred amulets.

Like perhaps some of the early Mahāyāna forest hermit Monks, or the later Buddhist Tantrics, they have become people of Power through their Meditative achievements. They are widely revered, worshipped, and held to be Arhats or (note!) Bodhisattvas.

In Mahāyāna Buddhism

Bodhisattva ideal

Mahāyāna Buddhism is based principally upon the path of a bodhisattva.

According to Jan Nattier, the term Mahāyāna ("Great Vehicle") was originally even an honorary synonym for Bodhisattvayāna, or the "Bodhisattva Vehicle."

The Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra contains a simple and brief definition for the term bodhisattva, which is also the earliest known Mahāyāna definition. This definition is given as the following.

- "Because he has Enlightenment as his aim, a bodhisattva-Mahāsattva is so called."

Mahāyāna Buddhism encourages everyone to become Bodhisattvas and to take the bodhisattva vows.

With these vows, one makes the promise to work for the complete Enlightenment of all Sentient beings by practicing the six perfections. Indelibly entwined with the Bodhisattva Vow is Merit transference (pariṇāmanā).

In Mahāyāna Buddhism Life in this World is compared to people living in a house that is on Fire.

People take this World as reality pursuing worldly projects and pleasures without realizing that the house is on Fire and will soon burn down (due to the inevitability of Death).

A bodhisattva is one who has a determination to free Sentient beings from Samsara and its cycle of Death, Rebirth and Suffering. This type of Mind is known as the Mind of Awakening (Bodhicitta). Bodhisattvas take bodhisattva vows in order to progress on the Spiritual path towards Buddhahood.

There are a variety of different conceptions of the nature of a bodhisattva in Mahāyāna.

According to some Mahāyāna sources a bodhisattva is someone on the path to full Buddhahood.

Others speak of Bodhisattvas renouncing Buddhahood.

According to the Kun-bzang bla-ma'i zhal-lung, a bodhisattva can choose any of three paths to help Sentient beings in the process of achieving Buddhahood. They are:

- king-like bodhisattva - one who aspires to become Buddha as soon as possible and then help Sentient beings in full fledge;

- boatman-like bodhisattva - one who aspires to achieve Buddhahood along with other Sentient beings and

- shepherd-like bodhisattva - one who aspires to delay Buddhahood until all other Sentient beings achieve Buddhahood. Bodhisattvas like Avalokiteśvara and Śāntideva are believed to fall in this category.

According to the Doctrine of some Tibetan schools (like Theravāda but for different reasons), only the first of these is recognized.

It is held that Buddhas remain in the World, able to help others, so there is no point in delay. Geshe Kelsang Gyatso notes:

- In reality, the second two types of Bodhicitta are wishes that are impossible to fulfill because it is only possible to lead others to Enlightenment once we have attained Enlightenment ourself.

Therefore, only king-like Bodhicitta is actual Bodhicitta.

Je Tsongkhapa says that although the other Bodhisattvas wish for that which is impossible, their attitude is sublime and unmistaken.

The Nyingma school, however, holds that the lowest level is the way of the king, who primarily seeks his own benefit but who recognizes that his benefit depends crucially on that of his kingdom and his subjects.

The middle level is the path of the boatman, who ferries his passengers across the river and simultaneously, of course, ferries himself as well.

The highest level is that of the shepherd, who makes sure that all his sheep arrive safely ahead of him and places their welfare above his own.

Ten grounds

According to many traditions within Mahāyāna Buddhism, on the way to becoming a Buddha, a bodhisattva proceeds through ten, or sometimes fourteen, grounds or bhūmis.

Below is the list of the Ten bhūmis and their descriptions according to the Avataṃsaka Sūtra and The Jewel Ornament of Liberation, a treatise by Gampopa, an influential teacher of the Tibetan Kagyu school.

(Other schools give slightly variant descriptions.)

Before a bodhisattva arrives at the first ground, he or she first must travel the first two of the Five Paths:

- the path of accumulation

- the path of preparation

The Ten grounds of the bodhisattva then can be grouped into the next three paths

- Bhūmi 1 the path of Insight

- bhūmis 2-7 the path of Meditation

- bhūmis 8-10 the path of no more learning

The chapter of Ten grounds in the Avataṃsaka Sūtra refers to 52 stages. The 10 grounds are:

- Great Joy: It is said that being close to Enlightenment and seeing the benefit for all Sentient beings, one achieves great Joy, hence the name. In this Bhūmi the Bodhisattvas practice all perfections (Pāramitās), but especially emphasizing Generosity (Dāna).

- Stainless]: In accomplishing the second Bhūmi, the bodhisattva is free from the stains of immorality, therefore, this Bhūmi is named "stainless". The emphasized perfection is Moral Discipline (śīla).

- Luminous: The third Bhūmi is named "luminous", because, for a bodhisattva who accomplishes this Bhūmi, the Light of Dharma is said to radiate for others from the bodhisattva. The emphasized perfection is Patience (kṣānti).

- Radiant: This Bhūmi is called "radiant", because it is said to be like a radiating Light that fully burns that which opposes Enlightenment. The emphasized perfection is vigor (Vīrya).

- Very difficult to train: Bodhisattvas who attain this Bhūmi strive to help Sentient beings attain maturity, and do not become emotionally involved when such beings respond negatively, both of which are difficult to do. The emphasized perfection is Meditative Concentration (Dhyāna).

- Obviously Transcendent: By depending on the perfection of Wisdom, [the bodhisattva) does not abide in either Saṃsāra or Nirvāṇa, so this state is "obviously transcendent". The emphasized perfection is Wisdom (prajñā).

- Gone afar: Particular emphasis is on the perfection of skillful means (upāya), to help others.

- Immovable: The emphasized Virtue is aspiration. This, the "immovable" Bhūmi, is the Bhūmi at which one becomes able to choose his place of Rebirth.

- Good Discriminating Wisdom: The emphasized Virtue is Power.

- Cloud of Dharma: The emphasized Virtue is the practice of primordial Wisdom.

After the Ten bhūmis, according to Mahāyāna Buddhism, one attains complete Enlightenment and becomes a Buddha.

With the 52 stages, the Śūraṅgama Sūtra recognizes 57 stages. With the 10 grounds, various Vajrayāna schools recognize 3–10 additional grounds, mostly 6 more grounds with variant descriptions.

A bodhisattva above the 7th ground is called a Mahāsattva. Some Bodhisattvas such as Samantabhadra are also said to have already attained Buddhahood.

School doctrines

Some Sutras said a beginner would take 3–22 countless eons (mahāsaṃkhyeya kalpas) to become a Buddha.

Pure Land Buddhism suggests buddhists go to the pure lands to practice. Tiantai, Huayan, Zen and Vajrayāna schools say they teach ways to attain Buddhahood within one karmic cycle.

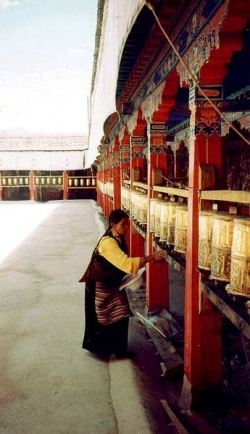

Various traditions within Buddhism believe in specific Bodhisattvas. Some Bodhisattvas appear across traditions, but due to Language barriers may be seen as separate entities.

For example, Tibetan Buddhists believe in various forms of Chenrezig, who is Avalokiteśvara in Sanskrit, Guanyin (Kwan-yin or Kuan-Yin) in China and Korea, Quan Am in Vietnam, and Kannon (formerly spelled and pronounced: Kwannon) in Japan.

Followers of Tibetan Buddhism consider the Dalai Lamas and the Karmapas to be an emanation of Chenrezig, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.

Kṣitigarbha is another popular bodhisattva in Japan and China. He is known for aiding those who are lost. His greatest compassionate vow is:

- If I do not go to the Hell to help the Suffering beings there, who else will go? ... if the hells are not empty I will not become a Buddha. Only when all living beings have been saved, will I attain Bodhi.

The place of a bodhisattva's earthly deeds, such as the achievement of Enlightenment or the acts of Dharma, is known as a Bodhimanda, and may be a site of pilgrimage.

Many temples and Monasteries are famous as bodhimandas; for instance, the island of Putuoshan, located off the coast of Ningbo, is venerated by Chinese Buddhists as the Bodhimanda of Avalokiteśvara.

Perhaps the most famous Bodhimanda of all is the Bodhi tree under which Śākyamuṇi achieved Buddhahood.

Source

[[Image:Bodhisattva.JPG|frame|Bodhisattva sangha from the Longchen Nyingtik field of merit)]

Bodhisattva (Skt.; Tib. བྱང་ཆུབ་སེམས་དཔའ་, chang chub sempa; Wyl. byang chub sems dpa' ) — someone who has aroused bodhichitta,

the compassionate wish to attain enlightenment for the benefit of all beings and also wishes to bring them to that state. It also refers to a sublime bodhisattva who has attained one of the ten stages of the bodhisattva path.

The Bodhisattva Path

Entry Point

The bodhisattvas practise on the basis of their wish to benefit others.

They are motivated by bodhichitta, which has as its focus all sentient beings and is characterized by the wish to establish them all at the level of perfect buddhahood, free from the causes and effects of suffering and endowed with all the causes and effects of happiness.

With this motivation, they take the bodhisattva vows of aspiration and application in the proper way, through the ritual of either the tradition of Profound View or Vast Conduct.

They then observe the points of discipline concerning what should be adopted and abandoned, and heal and purify any impairments.

View

Concerning the basis of their path, how they determine the view, if we speak in terms of philosophical tenets, the approach of Mind Only is to assert that outer objects are not real and all phenomena are but the inner mind, and to claim that the self-aware, self-knowing consciousness devoid of dualistic perception is truly real.

The approach of the Middle Way is to realize that all phenomena appear in the manner of dependent origination, but are in reality emptiness, beyond the eight extremes of conceptual elaboration.

Through these approaches, on the basis of the explanation of the two levels of reality, they realize completely the absence of any personal self or phenomenal identity.

Meditation

Concerning their path and how they practise meditation, the bodhisattvas realize and train in developing their familiarity with the indivisibility of the two levels of reality, and,

on the basis of the yogic meditation that unites shamatha and vipashyana, meditate sequentially on the thirty-seven factors of enlightenment while on the path of training.

Conduct

They practise the six transcendent perfections for their own benefit and the four means of attraction for the sake of others.

Results

They attain the level of buddhahood, which is the ultimate attainment in terms of both abandonment and realization since it means abandoning all that has to be eliminated, the two obscurations including habitual traces,

and realizing everything that must be realized, included within the knowledge of all that there is and the knowledge of its nature. They accomplish the two types of dharmakaya for their own benefit and the two types of rupakaya for the benefit of others.

Famous bodhisattvas

See Also

External Links

Source

RigpaWiki:Bodhisattva

bodhisattva (pu-sa): Literally, “enlightenment being.”

A holy being or saint who has become enlightened and who enlightens others, but is not yet a Buddha. Sometimes Buddhas will transform back into Bodhisattvas to help living beings.

There are small and great Bodhisattvas based on the their determination or mind set to save living beings.

If one does not have this mindset and uses a mundane mindset to view problems, then one is not a Bodhisattva.

A Bodhisattva is a living being who possesses supernatural powers, such as the power to transform into other forms.

He possesses wisdom, great compassion and great bodhichitta.

He does not mind sacrificing himself for the benefit of all living beings.

He teaches the Buddha-dharma to living beings so that they may become accomplished.

In mahayana Buddhism, a Bodhisattva is a being who seeks buddhahood through the systematic practice of the perfect virtues (paramitas) but who renounces complete entry into nirvana until all beings are saved.

A Bodhisattva is above the level of an Arhat. A Bodhisattva cannot be distinguished as being either male or female.

Some Bodhisattvas are with you every day and may appear as an ordinary being.

See Also

- “Sainthood” and “fifty-five bodhisattva stages.”

Source

bodhisattva

菩薩 (Skt; Jpn bosatsu )

One who aspires to enlightenment, or Buddhahood. Bodhi means enlightenment, and sattva, a living being.

In Hinayana Buddhism, the term is used almost exclusively to indicate Shakyamuni Buddha in his previous lifetimes.

The Jataka, or "birth stories" (which recount his past existences), often refer to him as "the bodhisattva."

After the rise of Mahayana, bodhisattva came to mean anyone who aspires to enlightenment and carries out altruistic practice.

Mahayana practitioners used it to refer to themselves, thus expressing the conviction that they would one day attain Buddhahood.

In contrast with the Hinayana ideal embodied by the voice-hearers and cause-awakened ones who direct their efforts solely toward personal salvation, Mahayana sets forth the ideal of the bodhisattva who seeks enlightenment both for self and others, even postponing one's entry into nirvana in order to lead others to that goal.

The predominant characteristic of a bodhisattva is therefore compassion.According to Mahayana tradition, upon embarking on their practice of the six paramitas, bodhisattvas make four universal vows:

(1) to save innumerable living beings,

(2) to eradicate countless earthly desires,

(3) to master immeasurable Buddhist teachings, and

(4) to attain the supreme enlightenment.

The six paramitas are

(1) almsgiving,

(2) keeping the precepts,

(3) forbearance,

(4) assiduousness,

(5) meditation, and (

(6) the obtaining of wisdom.

Some sutras divide bodhisattva practice into fifty-two stages, ranging from initial resolution to the attainment of enlightenment. Bodhisattva practice was generally thought to require successive lifetimes spanning many kalpas to complete.

From the standpoint of the Lotus Sutra, which recognizes that one can attain Buddhahood in one's present form, the bodhisattva practice can be completed in a single life-time.

In Japan, the title bodhisattva was occasionally given to eminent priests by the imperial court, or by their followers as an epithet of respect. It also was applied to deities.

When Buddhism was introduced to Japan, deities of the Japanese pantheon were regarded as afflicted with an assortment of flaws, delusions, and vices.

Later, their status was raised when they were identified with bodhisattvas due to the syncretism of Buddhism and Shintoism.

Great Bodhisattva Hachiman is an example of this.In terms of the concept of the Ten Worlds, the world of bodhisattvas constitutes the ninth of the Ten Worlds, describing a state characterized by compassion in which one seeks enlightenment both for oneself and others.

In this state, one finds satisfaction in devoting oneself to relieving the suffering of others and leading them to happiness, even if it costs one one's life.

See also