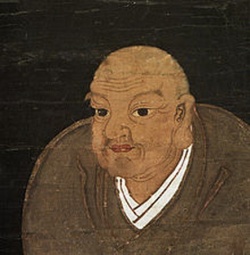

Nichiren

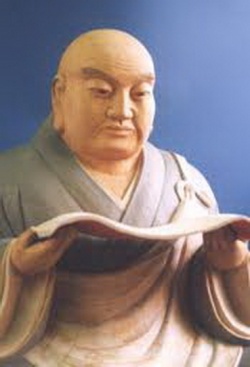

Nichiren (日蓮) (February 16, 1222 – October 13, 1282) was a Buddhist monk who lived during the Kamakura period (1185–1333) in Japan.

Nichiren taught devotion to the Lotus Sutra (entitled Myōhō-Renge-Kyō in Japanese)— which contained Gautama Buddha's teachings towards the end of his Life — as the exclusive means to attain Enlightenment.

Nichiren believed that the Sutra contained the essence of all of Gautama Buddha's teachings, of which related to the law of cause and effect and Karma.

This devotion to the Sutra entails the Chanting of Nam(u)-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō (referred to as "daimoku") as the essential practice of the teaching.

Nichiren Buddhism includes various schools with their own interpretations of Nichiren's teachings, the most prominent being Nichiren Shu, Nichiren Shoshu and Soka Gakkai; however, despite the differences between schools, all Nichiren sects share the fundamental practice of Chanting daimoku.

While virtually all Nichiren Buddhist schools regard him as a Reincarnation of the Lotus Sutra's Bodhisattva Superior Practices, Jōgyō Bosatsu (上行菩薩),

some schools of Nichiren Buddhism's Nikkō lineages regard him as the actual Buddha of this age, or The Buddha of the Latter day of the Law.

Life

Birth

Nichiren was born on February 16, 1222 in the village of Kominato, Nagase District, Awa Province (within present-day Chiba Prefecture). Nichiren's father, a fisherman, was Mikuni-no-Tayu Shigetada,

also known as Nukina Shigetada Jiro (d. 1258) and his mother was Umegiku-nyo (d. 1267).

On his birth, his parents named him Zennichimaro (善日麿?) which has variously been translated into English as "Splendid Sun" and "[[Virtuous Sun Boy[[" among others.

The exact site of Nichiren's birth is believed to be submerged off the shore from present-day Kominato-zan Tanjō-ji (小湊山 誕生寺), a temple in Kominato that commemorates Nichiren's birth.

In his own words about his birth, Nichiren stated that he was "the son of a chandala family who lived near the sea in Tojo in Awa Province, in the remote countryside of the eastern part of Japan."

Education

Nichiren began his Buddhist study at a nearby temple of the Tendai school, Seichō-ji (清澄寺, also called Kiyosumi-dera), at age 11. He was formally ordained at 16 and took the Buddhist name Zeshō-bō Renchō.

He left Seichō-ji shortly thereafter to study in Kamakura and several years later traveled to western Japan for more in-depth study in the Kyoto–Nara area, where Japan's major centers of Buddhist learning were located.

In 1233 he went to Kamakura, where he studied Amidism—a pietistic school that stressed salvation through the invocation of Amida (Amitābha), The Buddha of infinite Compassion—under the guidance of a renowned master.

After having persuaded himself that Amidism was not the true Buddhist Doctrine, he passed to the study of Zen Buddhism, which had become popular in Kamakura and Kyōto.

He then went to Mount Hiei, the cradle of Japanese Tendai Buddhism, where he found the original purity of the Tendai Doctrine corrupted by the introduction and acceptance of other doctrines, especially Amidism and Esoteric Buddhism.

To eliminate any possible doubts, Nichiren decided to spend some time at Mount Kōya,

the centre of Esoteric Buddhism, and also in Nara, Japan’s ancient capital, where he studied the Ritsu sect,

which emphasized strict monastic discipline and ordination.

During this time, he became convinced of the pre-eminence of the Lotus Sutra and in 1253, returned to Seichoji.

Initial teaching

On April 28, 1253, he expounded Nam(u)-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō for the first time, marking his Sho Tempōrin (初転法輪: "first turning the wheel of the Law").

With this, he proclaimed that devotion and practice based on the Lotus Sutra was the correct form of Buddhism for the current time.

At the same time he changed his name to Nichiren,nichi (日) meaning "sun" and ren (蓮) meaning "Lotus".

This choice, as Nichiren himself explained, was rooted in passages from the Lotus Sutra.

After making his declaration, which all schools of Nichiren Buddhism regard as marking their foundation (立宗: risshū), Nichiren began propagating his teachings in Kamakura,

then Japan's de facto capital since it was where the shikken (regent for the shogun) and shogun lived and the government was established.

He gained a fairly large following there, consisting of both priests and laity.

Many of his lay believers came from among the samurai class.

Among other things, in 1253 Nichiren predicted the Mongol invasions of Japan: a prediction which was validated in 1274.

Nichiren viewed his teachings as a method of efficaciously preventing this and other disasters:

that the best countermeasure against the degeneracy of the times and its associated disasters was through the activation of Buddha-nature by Chanting and the other practices which he advocated.

Treatise (first remonstrance)

Nichiren then engaged in writing, publishing various works including his Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論?): "Treatise On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land", his first major treatise and the first of three remonstrations with government authorities.

He felt that it was imperative for the sovereign to recognize and accept the singly true and correct form of Buddhism (i.e.,

立正: risshō) as the only way to achieve peace and prosperity for the land and its people and end their Suffering (i.e., 安国: ankoku).

This "true and correct form of Buddhism", as Nichiren saw it, entailed regarding the Lotus Sutra as the fullest expression of The Buddha's teachings and putting those teachings into practice.

Nichiren thought this could be achieved in Japan by withdrawing lay support so that the deviant monks would be forced to change their ways or revert to laymen to prevent starving.

Based on prophecies made in several sutras, Nichiren attributed the occurrence of the famines,

disease, and natural disasters (especially drought, typhoons, and earthquakes) of his day to teachings of Buddhism no longer appropriate for the time.

Nichiren submitted his treatise in July 1260.

Though it drew no official response, it prompted a severe backlash, especially from among priests of other Buddhist schools.

Nichiren was harassed frequently, several times with force, and often had to change dwellings.

When Nichiren is exiled in 1261, Nichirō wants to follow Nichiren; but Nichirō is forbidden to do so -- Postcard artwork, circa 1920s.

Nichirō agreed with Nisshō's defense of Nichiren as a Tendai reformer .

He founded a practice hall that became part of Ikegami Honmon-ji, the site of Nichiren's Death.

His school is now part of Nichiren-shū.

Nichiren was exiled to the Izu peninsula in 1261, and pardoned in 1263.

He was ambushed and nearly killed at Komatsubara in Awa Province in November 1264.

Failed execution attempt

The following several years were marked by successful propagation activities in eastern Japan that generated more resentment among rival priests and government authorities.

After one exchange with the influential priest, Ryōkan (良観), Nichiren was summoned for questioning by the authorities in September 1271.

He used this as an opportunity to make his second government remonstration, this time to Hei no Saemon (平の左衛門,

also called 平頼綱: Taira no Yoritsuna), a powerful police and military figure who issued the summons.

Two days later, on September 12, Hei no Saemon and a group of soldiers abducted Nichiren from his hut at Matsubagayatsu, Kamakura. Their intent was to arrest and behead him.

According to Nichiren's account, an astronomical phenomenon — "a brilliant orb as bright as the moon" — over the seaside Tatsunokuchi execution grounds terrified Nichiren's executioners into inaction.

The incident is known as the Tatsunokuchi Persecution and regarded as a turning point in Nichiren's lifetime called Hosshaku kenpon (発迹顕本).

Second exile

Unsure of what to do with Nichiren, Hei no Saemon decided to banish him to Sado, an island in the Japan Sea known for its particularly severe winters and a place of harsh exile.

This exile, Nichiren's second, lasted about three years and, though harsh and in the long term detrimental to his health, represents one of the most important and productive segments of his Life.

While on Sado, he won many devoted converts and wrote two of his most important doctrinal treatises, the Kaimoku Shō (開目抄:

"On the Opening of the Eyes" ) and the Kanjin no Honzon Shō (観心本尊抄:

"The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind" ) as well as numerous letters and minor treatises whose content containing critical components of his teaching.

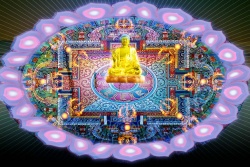

Gohonzon

It was also during his exile on Sado, in 1272, that he inscribed the first Gohonzon (御本尊). This mandala is a visual representation, in Chinese characters, of the Ceremony in the Air.

This ceremony is described in the 11th (Treasure Tower) to 22nd (Entrustment) chapters of the Lotus Sutra.

Within these chapters it is revealed that all persons can attain Buddhahood in this lifetime and Shakyamuni transfers the essence of the Sutra to the Bodhisattvas of the Earth led by Bodhisattva Superior Practices (Jogyo),

entrusting them with the propagation of the essence of the Sutra in the Latter Day of the Law.

For Nichiren, the Gohonzon embodies the eternal and intrinsic Law of Nam-Myoho-Renge-Kyo, which he identified as the ultimate Law permeating Life and the universe.

In this time he began to write his first prophecies .

Return to Kamakura

Nichiren was pardoned in February 1274 and returned to Kamakura in late March.

He was again interviewed by Hei no Saemon, who now was interested in Nichiren's prediction of an invasion by the Mongols. Mongol messengers

demanding Japan's fealty had frightened the authorities into believing that Nichiren's prophecy of foreign invasion would materialize (which it did in October; see Mongol Invasions of Japan).

Nichiren, however, used the audience as yet another opportunity to remonstrate with the government.

Retirement to Mt. Minobu

His third remonstration also went unheeded, and Nichiren—following a Chinese adage that if a wise man remonstrates three times but is ignored, he should leave the country—decided to go into voluntary exile at Mt. Minobu (身延山) in 1274.

With the exception of a few short journeys, Nichiren spent the rest of his Life at Minobu, where he and his disciples erected a temple, Kuon-ji (久遠寺), and he continued writing and training his disciples.

Two of his works from this period are the Senji Shō (撰時抄

"The Selection of the Time") and the Hōon Shō (報恩抄: "On Repaying Debts of Gratitude"), which, along with his Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論:

"On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land"), Kaimoku Shō ("The Opening of the Eyes"),

and Kanjin no Honzon Shō ("The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind"), constitute his Five Major Writings.

He also inscribed numerous Gohonzon for bestowal upon specific disciples and lay believers.

Many of these survive today in the repositories of Nichiren temples such as Taiseki-ji (大石寺) in Fujinomiya, Shizuoka Prefecture, which has a particularly large collection that is publicly aired once a year in April. Death

Nichiren spent his final years writing, inscribing Gohonzon for his disciples and believers, and delivering sermons.

In failing health, he was encouraged to travel to hot springs for their medicinal benefits. He left Minobu in the company of several disciples on September 8, 1282.

He arrived ten days later at the residence of Ikegami Munenaka, a lay believer who lived in what is now Ikegami, the site is marked by Ikegami Honmon-ji.

On September 25 he delivered his last sermon on the Risshō Ankoku Ron, and on October 8 he appointed six senior disciples—Nisshō (日昭), Nichirō (日朗), Nikkō (日興), Nikō (日向), Nichiji (日持), and Nitchō (日頂)—to continue leading propagation of his teachings after his Death.

Nichiren Shoshu believe that Nichiren designated five senior priests, and one successor, Nikko.

On October 13, 1282, Nichiren died in the presence of many disciples and lay believers.

His funeral and Cremation took place the following day.

His disciple Nikkō left Ikegami with Nichiren's ashes on October 21, reaching Minobu on October 25.

Nichiren's original tomb is sited, as per his request, at Kuonji on Mt. Minobu.

Nichiren’s identity and posthumous titles

In his writings, Nichiren refers to his identity in a variety of ways, nevertheless always related to the Lotus Sutra,

for example: "I, Nichiren, am the foremost votary of the Lotus Sutra". Of the many figures appearing in the Lotus Sutra,

Nichiren chose his spiritual identity as that of Bodhisattva Superior Practices,

and identified his goal as attaining Buddhahood: "From the beginning… I wanted to master Buddhism and attain Buddhahood".

In his post Tatsunokuchi's persecution writings, Nichiren referred to his person as parent, teacher and sovereign.

While some schools regard this as features attributed to Shakyamuni Buddha others underline that he identifies himself as a votary of the Lotos Sutra:

"Shakyamuni Buddha is the father and mother, teacher and sovereign to all living being...” and similarly mentioning in his letter 'The Opening of the Eyes':

“I, Nichiren, am sovereign, teacher, and father and mother to all the people...”.

After his Death, Nichiren has been known by several posthumous names intended to express respect toward him or to represent his position in The History of Buddhism.

Most common among these are Shōnin 日蓮聖人 Saint or Sage, and Daishōnin 日蓮大聖人 "Great Sage".

Preference for these titles generally depends on the school to which a person belongs,

with "Shōnin" being commonly used within Nichiren Shū, which regards Nichiren as a Buddhist reformer and embodiment of Bodhisattva Superior Practices, while "Daishōnin" is the title used by followers of most, but not all, of the schools and temples derived from the Nikkō lineage, most notably the Sōka Gakkai,

who regard Nichiren as 'The Buddha of the Latter Day of the Law' and also Nichiren Shōshū, who regard Nichiren as 'The True Buddha', or 'Buddha of True Cause'.

The Japanese imperial court also awarded Nichiren the honorific designations Nichiren Daibosatsu 日蓮大菩薩 "Great Bodhisattva Nichiren", and Risshō Daishi 立正大師 "Great Teacher Risshō;

the former title was granted in 1358, and the latter in 1922. Enlightenment and Buddhahood

In Nichiren Shoshu Nichiren is revered as 'The Buddha of True Cause' because, they believe,

he revealed the 'cause' of Buddhahood: Chanting Nam-myoho-renge-kyo.

Whereas Shakyamuni is seen as 'The Buddha of True Effect' as he only revealed the 'effect' of Buddhahood.

This is based on the passage in Chapter 16 of the Lotus Sutra that reads:

"Originally I Shakyamuni Buddha practiced the Bodhisattva way, and the Life that I acquired then has yet to come to an end"

Nichiren Shoshu, and also Soka Gakkai, interpret the passage to mean that Shakyamuni must have practiced something to attain Buddhahood, but in the Lotus Sutra he did not reveal what that practice was.

Whereas Nichiren taught the daimoku, Nam(u)-myoho-renge-kyo, which leads all beings to Buddhahood.

Soka Gakkai and Nichiren Shoshu conclude that it was because of the daimoku that Shakyamuni attained Buddhahood in the remote past.

Development of Nichiren's teachings

The Kamakura period of 13th century Japan, in which Nichiren was born - was characterised by natural disasters,

internal strife and confusion within Mahayana schools about whether: "...the world had further entered a period of decline" referring to the Latter Day of the Law.

Nichiren attributed the turmoil in society to the invalid teachings of the Buddhist schools of his time, including the Tendai sect in which he was ordained:

"It is better to be a leper who chants Nam-myōhō-renge-kyō than be a chief abbot of the Tendai school".

Examinations of such breaks and continuities have been useful in illuminating the sources of Nichiren's ideas and to what extent Nichiren's thought is original or derivative of his parent tradition.

Setting out to declare his own teachings of Buddhism, Nichiren started at the age of 32 by denouncing all Mahayana schools of his time and by declaring the correct teaching

as the Universal Dharma (Nam-Myōhō-Renge-Kyō) and Chanting as the only path for personal and social salvation.

At the age of 51, Nichiren inscribed the Object of Veneration in Buddhism, the Gohonzon,"never before known" as he described it.

Other contributions to Buddhism were the teaching of The Five Guides of Propagation,

The Doctrine of the Three Great Secret Dharmas and the teaching of The Three Proofs for verification of the validity of Buddhist doctrines.

There is a difference between Nichiren teachings and almost all schools of Mahayana Buddhism regarding the understanding of the Latter day of the Law, Mappō.

Mahayana teaches that the current age is that of decline of Shakyamauni's Buddhism and that a Future Buddha will appear to start Buddhism anew.

Nichiren, on the other hand, confirms that the teachings of the Lotus Sutra will flourish for all eternity, and that the Bodhisattvas of the Earth will propagate Buddhism in the future.

Nichiren criticized other Buddhist schools for their manipulations of the populace for political and religious control.

Citing Buddhist sutras and commentaries, Nichiren argued that the Buddhist teachings were being distorted for their own gain.

Nichiren stated his Criticism clearly, in his Risshō Ankoku Ron (立正安国論?):

"Treatise On Establishing the Correct Teaching for the Peace of the Land", his first major treatise and the first of three remonstrations with government authorities.

After Nichiren's Death, his teachings were interpreted in different ways.

As a result, Nichiren Buddhism encompasses several major branches and schools, each with its own Doctrine and set of interpretations of Nichiren's teachings. See Nichiren Buddhism.

Writings

A section of the Risshō Ankoku Ron

Konpon Ji Temple)] was built on Sado Island at the place where Nichiren lived during his exile.

Nichiren Memorial at Jisso Ji Temple on Sado Island

Some Nichiren schools refer to the entirety of Nichiren's Buddhism as his "lifetime of teaching".

Many of his writings still exist in his original hand, some as complete writings and some as fragments. Others survive as copies made by his immediate disciples.

His existing works number over 700, including transcriptions of orally delivered lectures, letters of remonstration and illustrations.

Nichiren declared that women could attain Enlightenment, therefore a great number of letters were addresses to female believers.

Some schools within Nichiren Buddhism consider this to be a unique feature of Nichiren's teachings and have published separate volumes of those writings.

In addition to treatises written in kanbun (漢文), a formal writing style modeled on classical Chinese that was the Language of government and learning in contemporary Japan,

Nichiren also wrote expositories and letters to disciples and lay followers in mixed-kanji–kana vernacular as well as letters in simple kana for believers who could not read the more-formal styles, particularly children.

He is also known for his "kanbun", many of his writings preserved in the libraries of the empire had been lost at the end of the Boshin War.

Some of Nichiren's kanbun works, especially the Risshō Ankoku Ron, are considered exemplary of the kanbun style, while many of his letters show unusual empathy and understanding for the down-trodden of his day.

Many of his most famous letters were to women believers, whom he often complimented for their in-depth questions About Buddhism while encouraging them in their efforts to attain Enlightenment in this lifetime.

During the pre-World War II period the Japanese government ordered Nichiren sects to delete various passages from his writing

and prophecies which were considered by the military government as a challenge to the supremacy of the emperor. List of writings

The Five Major Writings that are common to all Nichiren Schools are:

On Establishing the Correct teaching for the Peace of the Land (J. Rissho Ankoku Ron) - written between 1258-1260 CE.

The Opening of the Eyes (J. Kaimoku-sho) - written in 1272 CE.

The Object of Devotion for Observing the Mind(J. Kanjin-no Honzon-sho) - written in 1273 CE.

The Selection of the Time (J. Senji-sho) - written in 1275 CE.

On Repaying Debts of Gratitude (J. Ho'on-sho) - written in 1276 CE.

Nichiren Shoshu and SGI revere Ten Major Writings of Nichiren. These are the five listed above, and also :

On Chanting the Daimoku of the Lotus Sutra (J. Sho-hokke Daimoku-sho) - Written in 1260 CE.

On Taking the Essence of the Lotus Sutra (J. Hokke Shuyo-sho) - written in 1274 CE.

On the Four Stages of Faith and the Five Stages of Practice (J. Shishin Gohon-sho) - written in 1277 CE.

Letter to Shimoyama (J. Shimoyama Gosho-soku) - written in 1277 CE.

Questions and Answers on the Object of Devotion (J. Honzon Mondo-sho) - written in 1278 CE.