Kalachakra

Kalachakra is Sanskrit for "Wheel of Time." It is a complete, elaborately detailed, cosmology. It is founded in a tantric cosmogony -- a traditional sacred explanation of the creation and structure of All. In the description, the microcosm that is Man is not different from the macrocosm that is the Universe. Besides these two very complex "maps" -- one outside us, the other inside us, there is given a method -- a way to practice and apply this knowledge, in order to achieve ultimate happiness. Kalachakra (Shilunxu): Refers to the symbol (Namju Wangden in Tibetan) that represents this tantric teaching of the Kalachakra Dharma.

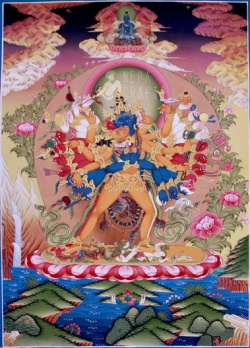

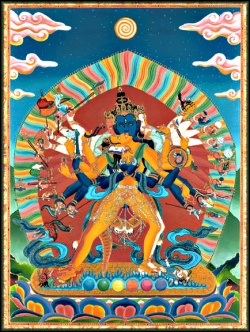

Kalachakra can also be translated, the Cycle of Time. It is the name of a highest level tantra and also the name of the dark blue male deity, whose golden consort is Vishvamata (Mother of the Universe.) The teaching of it, which is preparatory to the initiation, requires the construction of an intricate mandala, and to do it is an extensive undertaking.

Tantric Buddhism traces its origins to Buddha Sakyamuni's fourth "Turning of the Wheel," which is believed to have occurred at the stupa of Sri Dhanakosha near Amravali in Andhra Pradesh, India, in the year of His Enlightenment. All the high tantras such as Chakrasamvara, Guhyasamaya, and Kalachakra, derive from this.

The time of this transmission is variously given, though. For,

"According to one interpretation, the Kalachakra Tantra was first spoken by the Teacher Sakyamuni Buddha, at the time of the full moon in the third month of the year after his having shown the manner of becoming completely and perfectly enlightened. According to another interpretation, Sakyamuni, having showed the manner of becoming completely and perfectly enlightened, turned the three wheels of doctrine, and then one year before his passing away set forth the Kalachakra Tantra."

How does the Kalachakra fit into the Buddhist system?

The First Turning of the Wheel was at Sarnath, in the king's deer park. This was Shakyamuni Buddha's Discourse on the Four Noble Truths ("the truth of suffering ...") that he gave particularly to the five companions with whom he had been practicing various austerities. It forms the motivation or basis for all Buddhists.

The Second Turning of the Wheel took place at Vulture Peak outside Gaya and includes the discourse on compassion and Emptiness. It is exemplified by the Prajnaparamita literature -- a condensed form is the Heart (Skt : hridya) Sutra: "Form is Emptiness; Emptiness [is] Form." All Mahayana Buddhists have this teaching as the basis for their consideration of other beings.

The Third Turning of the Wheel was at Vaishali and some other places. It comprises the elucidation of "Emptiness" and its relation to Buddha Nature. The Mahaparanirvana Sutra and such Mahayana commentaries as the Uttaratantra Shastra address this. Not all Mahayana Buddhists have the same view of these texts.

According to Alexander Berzin, the system as taught by the Dalai Lama has three sources:

First, Buddha Shakyamuni taught it to an Indian audience that included the ruler of Shambhala. He, with his entourage of 96 others, returned home to set down what they had heard in The Root Kalachakra Tantra.

The Dalai Lama says,

- "... , unlike any other Tantra, Kalachakra was taught at the request of Chandrabhadra, King of legendary Shambhala, who, for the benefit of [his subjects) traveled to India and requested such a teaching from the Buddha. Kalachakra therefore has a special relationship to one particular land on this earth."

Seven reigns had passed when another ruler, Manjushri Ushas, as Shambala was being threatened by invasion, composed an Abridged Kalachakra Tantra. His son, Pundarika, wrote a commentary entitled, Stainless Light. Those two texts survive, but only fragments remain of the Root Tantra.

The Kalachakra teachings eventually reached India in the tenth century, brought by two masters who, although they had tried to reach the mysterious land did not succeed. They had visionary experiences of the system, however, and were able to record those. Naturally there were some discrepancies and consequently, four styles of Kalachakra practice evolved that differ in minor detail.

Those two versions may account for some differences in historic details, such as the King of Shambhala's name (also given as Suchandra.) Both names are also epithets for the Indian god, Shiva, whose many titles include chandra, Sanskrit for moon.

In the 11th century, the Kalachakra was brought to central Tibet by three different masters. Parts of the system also eventually made it north. The Tibetans made at least three different translations, and so there exist a number of variations. Today it is not possible to say which, if any of these, is the "correct" version, nor even the exact way of applying the practice. However, on the whole, the system is internally consistent as "about eighty percent of the material is shared in common."In the 17th century, the Kalachakra made it to Inner Mongolia and Beijing, the Manchu capital of China, and on to Amdo, the northeastern province of Tibet. In the 19th century, the system reached western (or, Outer) Mongolia and the Buryiat territory around Lake Baikal, Siberia.

By the early 20th century, it had reached Tuva in Turkestan and Kalmykia, the Mongolian region of European Russia. In 1915, the system had made a great enough impact that the Czar commissioned a Kalachakra temple for St. Petersburg.

Ling Rinpoche was the Dalai Lama's tutor and is the source of his transmission. It came down through Buston Rinchen Drupa (1290-1364) who combined two Tibetan translations with commentary. One was by Ra Dorje Drukpa and the other, by Dro Sherab Drak.

Surprisingly, some people see in the Dalai Lama's desire to pass on the Kalachakra vision, a kind of conspiracy to undermine other cultural or religious commitments. His Holiness does not claim that the Kalachakra is the one and only, superior and perfect practice for all people. Nor has he ever said that performing the initiation will automatically bring harmony to this complex world, although it may improve the condition for peace to flourish. Furthermore, he has always discouraged people from switching from one religion to another, and points out that the benefits of studying Buddha-dharma and doing certain practices can benefit people of all faiths. It has never been said that it is necessary to abandons one's native religion in order to become a Buddhist.

The Shambhala legend has it that political and religious discord was healed by the Kalachakra vision and practice, but no one would claim that it is the "only way to go." Furthermore, not all the Dalai Lamas have taken it up. The contemporary (the 14th) holder of that title enjoys doing it, teaching it and passing it on. People of all walks of life are welcome to attend for whatever reason -- out of curiosity, for educational reasons, from personal conviction, to support the projects of His Holiness or out of devotion to him.

What is a Monlam ?

Besides the widely publicized Kalachakra, the various Tibetan Buddhist denominations hold special prayer meetings (monlam) that also attract thousands of people. For example, in late 2002 and 2003, the Kagyu Monlam Chenmo took place near the spot of Buddha's Enlightenment. A Gelug Monlam was held at the maidan (parade ground) followed by a Kalachakra ritual teaching.

In 2003, the Nyingma order gathered for their annual Monlam Chenmo together in Bodhgaya from Feb. 2nd-12th, 2003. The Sakya chose Lumbini, Nepal, the birthplace of the Buddha for theirs, about the same date.

Many members of other religious groups attend these monlams for the purpose of experiencing the darshan of the Lamas.

happiness: This is the ultimate objective of all Buddhist practice, bearing in mind that we view existence as very long indeed -- transcending many lifetimes in various states and conditions according to Karma.

Turning of the Wheel: The Buddha's distinctive presentations of his doctrine are referred to in this way.

darshan: blessing of the presence of a holy being or relic.

Kālacakra (Sanskrit कालचक्र; Tibetan dus kyi 'khor lo) is a term used in Tantric Buddhism that means "time-wheel" or "time-cycles". It refers both to Tantric deities (Tib. Yi-dam | yidam) of Vajrayana Buddhism and to the philosophies and meditation practices contained within the Kālacakra Tantra and its many commentaries. The Kālacakra Tantra is more properly called the Kalachakra Laghutantra, and is said to be an abridged form of an original text, the Kalachakra Mulatantra which is no longer extant. Some Buddhist masters assert that Kalachakra is the most advanced and effective form of Vajrayana practice

The Kālacakra tradition revolves around the concept of time and cycles: from the cycles of the planets, to the cycles of human breathing, it teaches the practice of controlling the most subtle energies within one's body on the path to enlightenment. The Kalachakra deity represents a Buddha and thus omniscience. Since the Buddha is time and everything is under the influence of time, the Buddha therefore knows all. Similarly, the wheel is without beginning or end.

The Kalachakra Laghutantra

The Kalachakra Tantra is divided into five chapters, the first two of which are considered the “ground Kalachakra.” The first chapter deals with what is called the “outer Kalachakra”—the physical world, in particular the calculation system for the Kalachakra calendar. It also explicates the basic symbolism of the Kalachakra system

The second chapter deals with the “inner Kalachakra,” and concerns processes of human gestation and birth, the classification of the functions within the human body and experience, and the vajra-kaya—the expression of human physical existence in terms of channels, winds, drops and so forth. Human experience is described as consisting of four mind states: waking, dream, deep sleep, and a fourth state, the experience of sexual orgasm. The potentials (drops) which give rise to these states are described, together with the processes that flow from them.

The last three chapters describe the “other Kalachakra,” and deal with the path and fruition. The third chapter deals with the preparation for the meditation practices of the system, the initiations of Kalachakra. The fourth chapter explains the actual meditation practices themselves, both the meditation on the mandala and deity of Kalachakra in the generation process, and the perfection process of the Six Yogas. The fifth and final chapter describes the state of enlightenment that results from the practice.

Initiation

The Kalachakra initiations empower the disciple to practice the yoga of the Kalachakra tantra in the service of attaining Buddhahood. There are two main sets of initiations in Kalachakra, eleven in all. The first of these two sets concerns preparation for the generation stage meditations of Kalachakra and requires the use of the a Kalachakra powder mandala. The second concerns preparation for the completion stage meditations known as the Six Yogas of Kalachakra. Attendees who don’t intend to carry out the practice are generally only given the lower seven initiations.

Astrology

The phrase "as it is outside, so it is within the body" is often found in the Kalachakra tantra to emphasize the similarities between human beings and the cosmos; This concept is the basis for Kalachakra astrology, but also for even more profound connections and interdependence as taught in the Kalachakra literature.

In Tibet, the Kalachakra astrological system is one of the main building blocks in the composition of Tibetan astrological calendars. The astrology in the Kalachakra is not unlike the Western system, in which complicated calculations are required to determine, for example, the exact location of the planets.

History

Indian Origin

According to the Kalachakra legend, King Suchandra (Tib. Dawa Sangpo) of the northeastern Indian Kingdom of Shambhala requested teaching from the Buddha that would allow him to practice the dharma without renouncing his worldly enjoyments and responsibilities. In response to his request, the Buddha gave the first Kālachakra root tantra in Dhanyakataka (present day Amravati), a small town in Andhra Pradesh in southeastern India, supposedly emanating at the same time he was also delivering the Prajna Paramita sutras at Vulture Peak Mountain. Along with King Suchandra, ninety-six minor kings and emissaries from Shambhala were also said to have received the teachings. The Kalachakra thus passed directly to the Shambhala, where it was held exclusively for hundreds of years. Later Shambhalian kings, Manjushrikirti and Pundarika, are said to have condensed and simplified the teachings into the "Sri Kalachakra" and commentaries, all of which remain extant today as the heart of the Kalachakra.

There are presently two main traditions of Kalachakra, the Ra lineage (Tib. Rva-lugs) and the Dro lineage (Tib.'Bro-lugs). Although there were many translations of the Kalachakra texts from Sanskrit into Tibetan, the Ra and Dro translations are considered to be the most reliable (more about the two lineages below). The two lineages offer slightly differing accounts of how the Kalachakra teachings returned to India from Shambhala.

In both traditions, the Kalachakra and its related commentaries (sometimes referred to as the Bodhisattvas Corpus) returned to India during in 966 AD by an Indian Pandita. In the Ra tradition this figure is known as Chilupa, and in the Dro tradition as Kalachakrapada the Greater. Scholars such as Helmut Hoffman have suggested they are the same person. The first masters of the tradition disguised themselves with pseudonyms, so the Indian oral traditions recorded by the Tibetans contain a mass of contradictions.

Chilupa/Kalachakrapada is said to have set out to receive the Kalachakra teachings in Shambhala, along the journey to which he encounters the Kulika king Durjaya manifesting as Manjushri, who conferred the Kalachakra initiation on him based on his pure motivation.

Upon returning to India, Chilupa/Kalachakrapada is said to have defeated in debate Nadapada (Tib. Naropa), the abbot of Nalanda University, a great center of Buddhist thought at that time. Chilupa/Kalachakrapada then initiated Nadapada (who became known as Kalachakrapada the Lesser) into the Kalachakra, and the tradition as it was known thereafter in India and Tibet stemmed from these two. Nadapada established the teachings as legitimate in the eyes of the Nalanda community, and initiated into the Kālachakra such masters as Atisha (who, in turn, initiated the Kālachakra master Pindo Acharya (Tib. Pitopa)).

The Kalachakra tradition, along with all Vajrayana Buddhism, vanished from India in the wake of the Muslim invasions.

Kalachakra Tradition in Tibet

The Dro lineage was established in Tibet by a Kashmiri disciple of Nalandapa named Pandita Somanatha, who traveled to Tibet in 1027 (or 1064 AD, depending on the calendar used), and his translator Droton Sherab Drak Lotsawa, from which it takes its name. This Dro lineage has been sustained primarily by the Jonang tradition. The Ra lineage was brought to Tibet by another Kashmiri disciple of Nadapada named Samantashri, and translated by Ra Choerab Lotsawa (or Ra Dorje Drakpa). The Ra lineage became particularly important in the Sakya tradition of Tibetan Buddhism, where it was held by such prominent masters as Sakya Pandita (1182-1251), Drogon Chogyal Pagpa (1235-1280), Budon Rinchendrup (1290-1364), and Dolpopa Sherab Gyaltsen (1292-1361) who recieved a Sakya education at an early age but was one of the great Jonang masters. The latter two, both of whom also held the Dro lineage, are particularly well known expositors of the Kalachakra in Tibet, the practice of which is said to have greatly informed Dolpopa’s exposition of the zhentong or shentong view upheld by the Jonang. A strong emphasis on Kalachakra practice, along with exposition of the zhentong view, are the principle distinguishing characteristics of the Jonang tradition that Dolpopa upheld.

The teaching of the Kalachakra was further advanced by the great Jonang scholar Taranatha (1575-1634). In the 17th century, the Gelug-led government of Tibet outlawed the Jonang tradition for political reasons, closing down or forcibly converting most of its monasteries in Central Tibet. The writings of Dolpopa, Taranatha, and other prominent scholars were banned. Ironically, it was also at this time that the Gelug lineage absorbed much of its Kalachakra tradition from the Jonang.

Today Kalachakra is practiced by all five Tibetan traditions of Buddhism, although it appears most prominently in the Jonang and Gelug lineages. It remains central to the Jonang tradition which exists in Eastern Tibet. Khenpo Kunga Sherab Rinpoche is one contemporary Jonangpa master of the Kalachakra.

Kalachakra Practice Today in the Five Tibetan Buddhist Schools

Buton had considerable influence on the later development of the Gelug and Sakya traditions of Kalachakra, and Dolpopa on the development of the Jonang tradition on which the Kagyu and Nyingma draw. The Kagyu and Nyingma rely heavily on the extensive, Jonang-influenced Kalachakra commentaries of Ju Mipham and Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, both of whom took a strong interest in the tradition.

It should be noted, however, that there were many other influences and much cross-fertilization between the different traditions, and indeed His Holiness the Dalai Lama has asserted that it is acceptable for those initiated in one Kalachakra tradition to practice in others.

The Dalai Lamas have had specific interest in the Kālachakra practice, particularly the First, Second, Seventh, Eighth, and the current (Fourteenth) Dalai Lamas. The present Dalai Lama has given thirty Kalachakra initiations all over the world, and is the most prominent Kalachakra lineage holder alive today. Billed as the “Kalachakra for World Peace,” they draw tens of thousands of people. Generally, it is unusual for such advanced teachings to be given to large public assemblages, but the Kalachakra has long been an exception. The initiation is received as a blessing for the vast majority of those attending, although many attendees do subsequently engage in the practice as well.

Kalachakra Initiations given by H.H. XIV Dalai Lama

- 1. Norbu Lingka, Lhasa, Tibet, in May 1954

- 2. Norbu Lingka, Lhasa, Tibet, in April 1956

- 3. Dharamsala, India, in March 1970

- 4. Bylakuppe, South India, in May 1971

- 5. Bodh Gaya, India, in December 1974

- 6. Leh, Ladakh, India, in September 1976

- 7. Madison, USA, in July 1981

- 8. Dirang, Arunachal Pradesh, India, in April 1983

- 9. Lahaul & Spiti, India, in August 1983

- 10. Rikon, Switzerland, in July 1985

- 11. Bodh Gaya, India, in December 1985

- 12. Zanskar, Ladakh, India, in July 1988

- 13. Los Angeles, USA, in July 1989

- 14. Sarnath, India, in December 1990

- 15. New York, USA, in October 1991

- 16. Kalpa, HP, India, in August 1992

- 17. Gangtok, Sikkim, India, in April 1993

- 18. Jispa, HP, India, in August 1994

- 19. Barcelona, Spain, in December 1994

- 20. Mundgod, South India, in January 1995

- 21. Ulanbaator, Mongolia, in August 1995

- 22. Tabo, HP, India, in June 1996

- 23. Sydney, Australia, in September 1996

- 24. Salugara, West Bengal, India, in December 1996.

- 25. Bloomington, Indiana, USA, in August 1999.

- 26. Key Monastery, Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, India, in August 2000.

- 27a. Bodhgaya, Bihar, India, in January 2002 (postponed).

- 27b. Graz, Austria, in October 2002.

- 28. Bodh Gaya, Bihar, India, in January 2003.

- 29. Toronto, Canada, in April 2004.

- 30. Amaravati, Guntur Dt., Andhra Pradesh, India, in January 2006.

The Ninth Khalkha Jetsun Dhampa Rinpoche, H.E. Chogye Trichen Rinpoche, Ven. Jhado Rinpoche, and Ven. Gen Lamrimpa are also among the prominent Kalachakra masters of the Gelug school.

The Kalachakra tradition practiced in the Karma and Shangpa Kagyu schools is derived from the Jonang tradition , and was largely systematized by Jamgon Kongtrul the Great, who wrote the text that is now used for empowerment. The Second and The Third Jamgon Kongtrul Rinpoche (1954-1992) were also prominent Kalachakra lineage holders.

The chief Kalachakra lineage holder for the Kagyu lineage was Ven. Kalu Rinpoche (1905-1990), who gave the initiation in the United States in 1982 in Boulder, Colorado. Upon his death, this mantle was assumed by his heart son the Ven. Bokar Rinpoche (1940 - 2004), who in turn passed it on to Ven. Khenpo Lodro Donyo Rinpoche. Bokar Monastery, of which Donyo Rinpoche is now the head, features a Kalachakra stupa and is a prominent retreat center for Kalachakra practice in the Kagyu lineage. Ven. Tenga Rinpoche is also a prominent Kagyu holder of the Kālachakra; he gave the initiation in 1985 in Kuala Lumpur/Malaysia and Füssen/Germany, and in 2005 in Kathmandu/Nepal and in Grabnik/Poland. Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoche, while not a noted Kalachakra master, became increasingly involved later in his life with what he termed Shambhala teachings, derived from the Kalachakra tradition, in particular, the mind terma which he claimed to have received from the Kulikas.

Among the prominent recent and contemporary Nyingma Kalachakra masters are H.H. Dzongsar Khyentse Chökyi Lodrö (1894-1959), H.H. Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche (1910-1991), H.H. Penor Rinpoche, and Ven. Orgyen Kusum Lingpa Rinpoche.

The Jonang tradition has placed great emphasis on maintaining the practice lineage of the Kalachakra Tantra, and the Six Yogas of the Kalachakra completion phase in particular. Jonang Kalachakra practice along with its extensive guidance instructions has continued in an unbroken lineage from the Kalkins of Shambhala to the present-day Jonang masters. Among the great living Jonang exemplars is Khenpo Kunga Sherab Rinpoche.

His Holiness Sakya Trizin, the present head of the Sakya lineage, has given the Kalachakra initiation many times and is a recognized master of the practice.

Controversy

The Kalachakra Tantra has occasionally been the center of controversy because the text contains passages which are sometimes seen as demonizing the Abrahamic religions, particularly Islam. Further, it contains the prophecy of a future holy war between Buddhists and so-called "barbarians" (Skt. mleccha), which is sometimes interpreted as encouraging inter-religious conflict. An alternate intepretion takes the description of "holy war" less literally, believing that it refers to the inner battle of the religious practitioner against inner demonic and barbarian tendencies.

Source