Experience, The True Self, & The Individual Self

Experience, The True Self, & The Individual Self

Stating that dharmas are the fundamental constituents of reality is only meaningful in a context wherein the significance of “reality” is understood – and understood as somehow distinct from “dharmas.” As abstract generalizations “2+2” and “4” are merely two ways of stating the same thing; as experiential manifestations “2+2” and “4” can be distinctly different (e.g. a carpenter wants 2 nails at each end of a board, she calculates 4 nails per board). Therefore, we use the term “reality” for the actual manifestation of our experience of/as a “self.” For the only reality anyone has ever known is the experience of something (a thing, being, or event) or experience as something (a thing, being, or event) – the experience of “an other” or experience as “a self.” Thus, Dogen points out:

When speaking of consciousness of self and other, there is a self and an other in what is known; there is a self and an other in what is seen.

Shobogenzo, Shoaku Makusa, Hubert Nearman

One thing this means is that all three, “experience” (consciousness), “self,” and “other” presuppose each other, or in Buddhist terms, are interdependent. Therefore, to speak of “experience” is to speak of self and other, to speak of “self” is to speak of experience and other, etc. With this in mind, our initial statement (i.e. dharmas are the fundamental constituents of reality) could be accurately expressed as, dharmas are the fundamental constituents of experience, or dharmas are the fundamental constituents of self, or dharmas are the fundamental constituents of other – each of these expressions identify “dharmas” with the reality of “experience,” “self,” and “other.”

Nevertheless, it is difficult to deny that the term “self” seems, or feels more intimate, more meaningful, thus less alien and less abstract than “other” and “experience.” Therefore, we accept the Buddhist view that experience, self, and other are mutually inclusive and of equal status, and also follow Buddhism’s general practice of opting to utilize the term “self” as the primary metaphor for reality. To sum up and clarify; “self” (which presupposes “experience” and “other”) is the root metaphor of reality, thus the primary principle of Zen practice-enlightenment.

Before proceeding, a brief comment on a side issue related to the self as the primary metaphor of Zen is in order. It is axiomatic in Zen that authentic (i.e. intentional and effective) practice-enlightenment can only begin when the true nature of the self is experientially verified. Thus, the initial experience of true nature, often called “seeing true nature” (kensho), or “seeing Buddha” (kenbutsu), is naturally emphasized in Zen. The emphasis on an initial awakening, while perfectly understandable, has led many to over-estimate its import in the overall actualization of Zen practice-enlightenment – many have even concluded that it is the be-all and end-all of Zen. Here, then, let it be said that it is crucial to understand that awakening to the true nature of the self is the beginning, not the end of Zen practice-enlightenment.

Now, let us proceed by taking up what may be the thorniest question of all; who or what is it that we refer to as “we?” What is this “self” whose “true nature” the classic Zen masters are continuously urging us to awaken to? The majority of contemporary books whose subject centers on the “self,” books on health, psychology, religion (including Zen), and even self-help, show a marked propensity to avoid defining what it is they mean by the “self.” Like these books, the general population seems to assume that the meaning of “self” is self-evident. Nevertheless, when we compare how particular individuals explain their understanding of the self we find a multitude of differences and disagreements as well as a vast amount of obscurity, vagueness, and confusion. Because we view this writing, like all manner of expression, as a self-expression (i.e. an expression of the self, by the self, to the self) on the true nature of the self, we (i.e. the self) need to attempt to present a general outline of our understanding of the self here.

In Buddhism, “self” (Sanskrit: Atman, or Pali: Atta), like the Old English “aethm” and German “atem,” etymologically means “breath,” thus connoting “life,” “spirit,” “inspiration,” and perhaps most significantly “consciousness.” At the same time, “self” (sometimes used synonymously with “soul,” “ego,” “person,” etc.) is often used in a manner indicative of a “separate individual,” “particular being,” or “independent entity.” It is primarily in this latter sense of the term that the central tenet of Buddhist doctrine, “no-self” or “non-self” (anatman), is addressed. This tenet asserts, briefly, that no independent self (separate, enduring entity) exists.

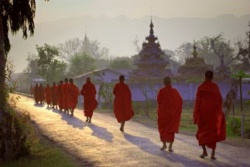

As long as the term “self” is understood in a way that leaves unsettled the impossibility for a self to exist as an independent entity, it fails to qualify as Buddhist, and indeed must be considered non-Buddhist. Nevertheless, this does not mean that any and all notions of “self” are therefore rejected or prohibited by Buddhism – even the earliest and most conservative forms of Buddhism recognized the importance of, and developed sophisticated approaches to, the inarguably existent and dynamic experience of human subjectivity. It is fair to say that the culminating schools of Mahayana Buddhism all achieved elaborately comprehensive visions of the self that ably accounted for all aspects of subjectivity without violating the tenet of “no-self.”

Generously, and unabashedly borrowing and adapting from the Huayen, Tendai, and other Buddhist schools (as well as from Taoism and Confucianism), Zen developed and utilized a number of doctrines and methods to deal with a “self” that effectively harmonizes with “no-self.” And accordingly, whether in terms of “ordinary beings and Buddhas,” “false mind and true mind,” “guest and host,” or similar variations, the “self” gradually but unvaryingly realized an increasing potential of mythological significance. As with the term “soul” in Neoplatonism (only developing unhindered for much longer), it became, and continues to be possible in Buddhism to use “self” in speaking of the individual self (e.g. myself, yourself, herself, etc.) and the world self (e.g. the universe, great self, Buddha, etc.) at once, that is, to communicate meaningfully and truthfully about both the individual and the world. Of course, it remains possible for “self” to distinctly refer to one or the other; the ordinary, personal, or ego self, or the original, great, or true self. Which “self” (i.e. the individual, the world, or both) is meant in a particular instance is usually easily determined by its context.

Having noted the variety of dharmas that can be illumined by the term, let us now consider the actual nature of the several particulars designated as “self.” We will begin with the individual self, that is, the ordinary, personal, or ego self – the self we commonly identify as “our self.” Generally, the individual self is the subject of experience. To clarify, first note that any (and every) sense of “self” is by definition divided by a sense of “self” and “other than self.” Recall Dogen’s words above:

When speaking of consciousness of self and other, there is a self and an other in what is known; there is a self and an other in what is seen.

Shobogenzo, Shoaku Makusa, Hubert Nearman

It should now be clear that the content of experience (i.e. an “object of consciousness”) is experienced by the individual self as something distinct from, or other than the individual self. In short, then, the individual self is the “what” that is experienced as being independent of the content (object) of experience.

Now we are ready to consider the world self, that is, the universal, great, or true self – the self that Buddhism often identifies as “Buddha.” In general, the world self is the whole universe, the totality of existence-time. Whereas the individual self is the subject of experience as distinct from the object of experience, the “true” self is inclusive of both the subject and the object of experience. In the context of Dogen’s expression, the individual self is the self of “self and other” (i.e. the self distinct from the other); the world self is “what is known” and “what is seen,” which, as Dogen points out, is inclusive of both “a self and an other.”

We make haste to point out that the perspective of the “world self” denies neither the reality nor the significance of the “individual self.” In contrast to the assertions of some contemporary “Zen teachers,” the individual self is not illusory or provisional, but rather a real eternal constituent of the world self – is in fact wholly constituted of the world self. In short, while the world self is not wholly contained by the individual self (far from it!), the individual self is nevertheless wholly contained within the world self, thus wholly contained within the totality of existence-time.