Karma: Damma

karma

業 (Skt; Pali kamma; Jpn go )

Potentials in the inner, unconscious realm of life created through one's actions in the past or present that manifest themselves as various results in the present or future. Karma is a variation of the Sanskrit karman, which means act, action, a former act leading to a future result, or result. Buddhism interprets karma in two ways: as indicating three categories of action, i.e., mental, verbal, and physical, and as indicating a dormant force thereby produced. That is, one's thought, speech, and behavior, both good and bad, imprint themselves as a latent force or potential in one's life.

This latent force, or karma, when activated by an external stimulus, produces a corresponding good or bad effect, i.e., happiness or suffering. There are also neutral acts that produce neither good nor bad results. According to this concept of karma, one's actions in the past have shaped one's present reality, and one's actions in the present will in turn influence one's future. This law of karmic causality operates in perpetuity, carrying over from one lifetime to the next and remaining with one in the latent state between death and rebirth.

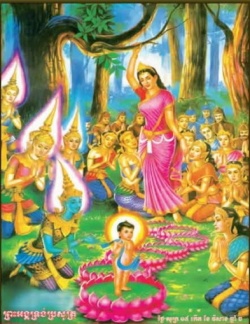

It is karma, therefore, that accounts for the circumstances of one's birth, one's individual nature, and in general the differences among all living beings and their environments. It was traditionally viewed as a natural process in which no god or deity could intervene. The Hindu gods, in fact, were subject to the same law of karma as people, having become gods supposedly through the creation of good karma. The idea of karma predates Buddhism and was already prevalent in Indian society well before the time of Shakyamuni. This pre-Buddhist view of karma, however, had an element of determinism, serving more to explain one's lot in life and compel one to accept it than inspiring hope for change or transformation. The Brahmans, who were at the top of the Indian class structure by birth, may well have emphasized this view to secure their own role. The idea of karma was further developed, however, in the Buddhist teachings.

Shakyamuni maintained that what makes a person noble or humble is not birth but one's actions. Therefore the Buddhist doctrine of karma is not fatalistic. Rather, karma is viewed not only as a means to explain the present, but also as the potential force through which to influence one's future. Mahayana Buddhism holds that the sum of actions and experiences of the present and previous lifetimes are accumulated and stored as karma in the depths of life and will form the framework of individual existence in the next lifetime. Buddhism therefore encourages people to create the best possible karma in the present in order to ensure the best possible outcome in the future. In terms of time, some types of karma produce effects in the present lifetime, others in the next lifetime, and still others in subsequent lifetimes. This depends on the nature, intensity, and repetitiveness of the acts that caused them. Only those types of karma that are extremely good or bad will last into future existences. The other, more minor, types will produce results in this lifetime. Those that are neither good nor bad will bring about no results.

Karma is broadly divided into two types: fixed and unfixed. Fixed karma is said to produce a fixed result—that is, for any given fixed karma there is a specific effect that will become manifest at a specific time. In the case of unfixed karma, any of various results or general outcomes might arise at an indeterminate time. Irrespective of these differences, the Buddhist philosophy of karma, particularly that of Mahayana Buddhism, is not fatalistic. No ill effect is so fixed or predetermined that good karma from Buddhist practice in the present cannot transform it for the better. Moreover, any type of karma needs interaction with the corresponding conditions to become manifest.

See also; fixed karma; unfixed karma.