Mahasiddha, (maha meaning ''great'' and siddha meaning ''adept'')

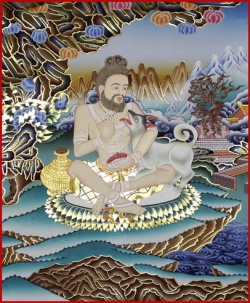

Mahasiddha, (maha meaning "great" and siddha meaning "adept") is a term for someone who embodies and cultivates siddhi of perfection. They are a type of eccentric yogi in both Hinduism and Vajrayana Buddhism. Mahasiddhas were tantric practitioners, or tantrikas who had sufficient attainments to act as a guru or tantric master. A siddha is an individual who, through the practice of sadhana, attains the realization of siddhis, psychic and spiritual abilities and powers. Their historical influence throughout the Indic and Himalayan region was vast and they reached mythic proportions which is codified in their songs of realization and hagiographies, or namthar, many of which have been preserved in the Tibetan Buddhist canon. The Mahasiddha are acknowledged as the founders of many Indian and Buddhist traditions and lineages.

Robert Thurman explains the symbiotic relationship between Tantric Buddhist communities and the Buddhist universities such as Nalanda which flourished at the same time:

"The Tantric communities of India in the latter half of the first Common Era millennium (and perhaps even earlier) were something like “Institutes of Advanced Studies” in relation to the great Buddhist monastic “Universities.” They were research centers for highly cultivated, successfully graduated experts in various branches of Inner Science (adhyatmavidya), some of whom were still monastics and could move back and forth from university (vidyalaya) to “site” (patha), and many of whom had resigned vows of poverty, celibacy, and so forth, and were living in the classical Indian saiñnyãsin or sãdhu style. I call them the "psychonauts" of the tradition, in parallel with our “astronauts,” the materialist scientist-adventurers whom we admire for their courageous explorations of the “outer space” which we consider the matrix of material reality. Inverse astronauts, the psychonauts voyaged deep into “inner space,” encountering and conquering angels and demons in the depths of their subconscious minds."

It was the Mahasiddhas who instituted the practices that birthed the Inner Tantras of Dzogchen practiced by the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. The other schools of Tibetan Buddhism and other Vajrayana Buddhists such as Shingon Buddhism practice Mahamudra meditation, also a practice initiated by the original Buddhist Mahasiddhas.

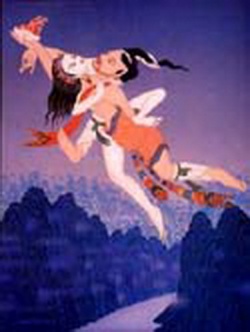

Mahasiddhas represent the mystical and unconventional which, in tantric thinking, is often associated with the most rarefied and sublime levels or states of spiritual enlightenment and realisation. They are typically contrasted with arhats, austere saints, though this description is also suitable for many of the Mahasiddhas.

Abhayadatta Sri is an Indian scholar of the 12th century who is attributed with recording the hagiographies of the eighty-four siddha in a text known as The History of the Eighty-four Mahasiddhas.

Keith Dowman holds that the eighty-four Mahasiddha are spiritual archetypes:

"The number eighty-four is a "whole" or "perfect" number. Thus the eighty-four siddhas can be seen as archetypes representing the thousands of exemplars and adepts of the tantric way. The siddhas were remarkable for the diversity of their family backgrounds and the dissimilarity of their social roles. They were found in every reach of the social structure: kings and ministers, priests and yogins, poets and musicians, craftsmen and farmers, housewives and whores.

The non-monastic Mahasiddha Dharma is composed of artists, business people, healers, family people, politicians, nobility, prostitutes and outcasts. The Mahasiddhas were a diverse group of people who were practical, committed, creative and engaged with their world. As a collective, their spirituality may be viewed as key and essential to their lives; simple, in concert and accord with all aspects of their lived experience. The basic elements of the lives of the Mahasiddas included their diet, physical posture, career, relationships; indeed "ordinary" life and lived experience were held as the principal foundation and fodder for realization. As siddhas, their main emphasis in spirituality and spiritual discipline was a direct experience of the sacred and spiritual pragmatism."

Reynolds (2007) states that the mahasiddha tradition:

...evolved in North India in the early Medieval Period (3-13 cen. CE). Philosophically this movement was based on the insights revealed in the Mahayana Sutras and as systematized in the Madhyamaka and Chittamatrin schools of philosophy, but the methods of meditation and practice were radically different than anything seen in the monasteries.

Mahasiddhas are a form of bodhisattva, meaning they have the spiritual abilities to enter nirvana whenever they please, but they are so compassionate they resolve to remain in samsara to help others. Mahasiddhas are often associated with historic persons, but nonetheless typically have magical powers or siddhi which they achieve by the efficacy of their spiritual practice.

Reynolds (2007) proffers that the mahasiddha tradition:

...broke with the conventions of Buddhist monastic life of the time, and abandoning the monastery they practiced in the caves, the forests, and the country villages of Northern India. In complete contrast to the settled monastic establishment of their day, which concentrated the Buddhist intelligensia in a limited number of large monastic universities, they adopted the life-style of itinerant mendicants, much the wandering Sadhus of modern India.

The mahasiddha tradition may be conceived and considered as a cohesive body due to their spiritual style, sahaja; which was distinctively non-sectarian, non-elitist, non-dual, non-elaborate, non-sexist, non-institutional, unconventional, unorthodox and non-renunciate. The mahasiddha tradition arose in dialogue with the dominant religious practices and institutions of the time which often foregrounded practices and disciplines that were over-ritualized, politicized, exoticized, excluded women and whose lived meaning and application were largely inaccessible and opaque to non-monastic peoples.

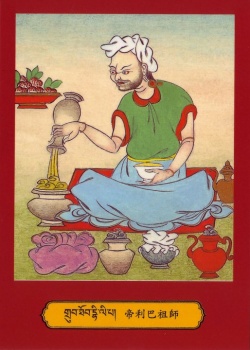

Simmer-Brown (2001: p. 127), in her exposition of the charnel ground conveys how great mahasiddhas in the Nath and Mantrayana Buddhadharma traditions such as Tilopa (988–1069) and Gorakṣa (fl. 11th – 12th century) yoked adversity to till the soil of the path and accomplish the fruit, the "ground" of realization; worthy case-studies for those with spiritual proclivity:

The charnel ground is not merely the hermitage; it can also be discovered or revealed in completely terrifying mundane environments where practitioners find themselves desperate and depressed, where conventional worldly aspirations have become devastated by grim reality. This is demonstrated in the sacred biographies of the great siddhas of the Vajrayāna tradition. Tilopa attained realization as a grinder of sesame seeds and a procurer for a prominent prostitute. Sarvabhakṣa was an extremely obese glutton, Gorakṣa was a cowherd in remote climes, Taṅtepa was addicted to gambling, and Kumbharipa was a destitute potter. These circumstances were charnel grounds because they were despised in Indian society and the siddhas were viewed as failures, marginal and defiled.