The Sacred Life of Tibet

By Keith Dowman

'The Sacred Life of Tibet is an introduction to the inner, visionary, life of the Tibetan Buddhist pilgrim as he moves from power place to power place in Tibet.

To travel in sacred Tibet, the Holy Land of Asia, is to embark on a mystical journey into the sacred space of Tibetan Buddhism a space quite distinct from the political and social space of Chinese-occupied Communist Tibet, and perhaps, from ordinary consciousness.

This work describes the mystical landscape and mindscape that the pilgrim moves through and the gods and demons, Buddhas, bodhisattvas, yogis and magicians who populate that space.

It also describes the rituals and meditations that open the door to experience of the mystic realm.'

'The first of the book’s five sections, Visionary Tibet, describes the Shaman’s vision of gods, demons and spirits and then shows how that vision is transformed into the Buddhist vision through binding demons into the mandalas of buddha-deities.

It also shows how the chaotic landscape is envisioned as mandalas of these buddha-deities.

The second section relates the history of Bon and Buddhism in Tibet and describes the schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

The third section deals with art and iconography as a means of entry into the [[mystical] tantric realm]].

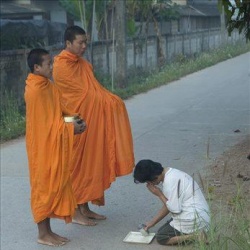

The fourth section is entitled the Yoga of Pilgrimage and describes the activity of the pilgrim in his quest for blessing and realization.

The fifth section describes the mystical significance of mountains and lakes, caves and hidden valleys, monasteries and temples, chortens and cairns and sky-burial sites with detailed reference to the principal power places of Tibet.

The final section is a gazetteer of the main power places of Tibet which are located on the maps provided.

An essay on the Tibetan diaspora and Tibetan Buddhism in the West completes the work.'

'This is a well-structured overview of what makes Tibet and its culture so fascinating.

The numinous peculiarities of Tibetan culture pertaining to religion, spirituality and magic are cataloged, examined in detail and methodically explained...

The various levels of the visionary aspects of Tibet are enthrallingly depicted in the context of the entire three-dimensional mandala of Buddhist cosmology...

So the fascinating and complex background of Tibetan culture is put into well-ordered perspective in nitty gritty detail, and this absorbing and well-written book is fully accessible to anyone with a basic grounding in the subject.'

Sean Jones in Tibet Foundation Newsletter.

The Sacred Life of Tibet is a scholarly book that covers Tibet's history, its geography, its culture, its religious evolution and its spiritual essence.

It is not just a well-researched book but one written will profound knowledge and feeling for the place. Keith Dowman is a leading world expert on Tibetan Buddhism. Marita Crawley in Light

Contents of The Sacred Life of Tibet

==The Shaman's Vision==

From the very beginning of human habitation in Tibet the principal religious preoccupation was with the harshness and hostility of the physical environment.

Before Buddhism, with its emphasis on morality, awareness and liberation, can come into focus, it was and still is necessary to come to terms with the landscape and the elemental powers that inhabit it.

Taming the landscape is the principal concern of the shaman and entering into his vision we enter the mythic realm of sacred Tibet.

The shaman's vision is a holistic vision where the distinction between the outer physical environment and the inner human being is blurred.

In the shaman's mindscape there is no radical distinction between outer phenomena and inner Noumea

.

Human consciousness encompasses the totality of possibility.

This is a pre-rational mindstate.

The development of consciousness that occurred in the Western mind after the Renaissance and the scientific enlightenment with the growth of rational, logical, thought processes, undermined this holistic vision of reality.

As the conceptual capacity of the mind increased, so did our alienation from a sense of oneness with the environment. Outer phenomena became separate from us and became objects of alienated scientific observation.

An acute separation - a dualism - of self and other evolved. Rational consciousness, indeed, depends upon the suppression of the noumena of the holistic mind.

The alienated dualistic mindstate of Western man has grown like a cancer to the point where we can only gain access to vestiges of the holistic shamanistic vision by damaging the psyche and entering an atavistic stratum of consciousness that is conventionally labelled insane.

The argument between holistic shamanistic consciousness and rational dualistic mind is not relevant here.

But it is necessary to accept the reality and validity of the holistic, mythic, vision of the shaman to understand the dimensions of his vision, his spiritualistic terminology and the methods he uses to transform the landscape and its spiritual phenomena, and to enter into sacred Tibet.

It may be useful to conceive of his vision as an internalisation of all apparently external phenomena through a process of 'seeing' that cuts through the duality of ordinary perception where self and other, physical and mental, inside and outside, are separate.

In the sphere of unitary perception all elements of every perceptual situation are interlinked: each sensory perception is a totality involving the entire cosmos, and thus it is called holistic - entire and complete.

The shaman is a magician able to manipulate, to pacify, to control or to subjugate the spiritualistic energies resident in the environment.

These energies may be elemental, animal or vegetable, human or relating to the realms of gods, demons and spirits.

Through his magic he can influence the elements responsible for rainfall, drought and flood, earthquake, avalanche and landslide, and thunder and lightening.

He can control the fertility of the soil assuring bounteous crops and averting famine.

He can prevent diseases of men and cattle.

He can protect the lives of men and women and the lives of their animals, the fertility of their crops, and their reproductive potency.

He can foretell the future and influence family and political affairs.

The cosmology of the shaman's mythic realm is best described in the conventional shamanic terms of the three realms of existence.

This is well known in Tibet, but also in its essence throughout South and South-East Asia.

The three realms of existence are:

<poem>

the sky,

the earth and

the subterranean realm.

These three spheres are inhabited and governed by three distinct categories of beings.

The gods live in the sky above, serpent spirits live in the earth below, and human beings live on the earth in between.

In elemental terms, the sky above is the domain of space, air and fire, the subterranean realm is the sphere of earth and water, and all the elements are present in the middle realm, the domain of human beings.

By 'gods' is understood gods (lha), demons (dre) and the innumerable spirits of various kinds.

Serpent spirits (lu, nagas) are demi-gods, and there are other various spirits that live in the netherworld.

The human mind in the middle realm is the stage on which these gods, demons and spirits interact with human beings.

The sky-gods include the gods like Brahma of the Hindu pantheon and spirits like the Odour-eaters (driza), but the sky-gods who loom largest in the Tibetan mythic vision are those who live on the mountain peaks, the mountain gods (noijin and nyen).

These most powerful of the entities of the pantheon, male or female, seem actually to be confounded with the mountains themselves.

They are warrior gods, quick to anger, jealous and violent, and their nature is power.

From the human point of view they are trouble-makers, tormentors, terrorists, devils, sitting on their mountain thrones raining down affliction, with little or no cause, upon their human quarry.

Their responses are like the reactions of irritable, violent, uptight drunks. Loitering on the passes, unless they are propitiated with offerings they are lethal to travelers - their breath is poisonous.

They shape-shift according to their mood and their need.

The Indian yaksha Ravana, who abducted Rama's wife Sita to his Sri Lankan lair, was a mountain god, but he lacks the feral savagery of the Tibetan variety.

The mountain gods are territorial lords - the greater the mountain the greater their territory.

Nyenchen Thanglha residing on the mountain of the same name in a range that dominates both the Northern Plains and Central Tibet is like the mountain god-king of the whole of Tibet.

The god of the mountain that physically dominates a valley probably rules that valley, as Yarlha Shampo, for example, rules the Yarlung Valley.

Every small valley has its own mountain residence of its mountain god.

What ties the human inhabitants most securely to the mountain god and his whims and moods is their relationship of grandson to grandfather.

The mountain gods are the original ancestors of the tribes of Central Tibet and they have a certain responsibility to their offspring, although even careful ritual propitiation does not necessarily bring looked for protection from these irresponsible guardians.

They are as capricious as the weather, which is a principal method of cowing and tyrannizing their progeny.

Mountain gods are propitiated with complex ritual and offering.

The chief residents of the subterranean realm are the serpent spirits, demi-gods, male and female (lu and luma).

They can be conceived animistic-ally as the spirits of earth and water and everything that is contained within these elemental spheres.

In a special way they are the guardians of ecological balance, a highly conservative force inhibiting human interference with the earth and what is in the earth.

They are the foot soldiers of a semi-divine natural authority that orders mankind's relationship with his terrestrial environment.

While the mountain gods rule with a heavy-handed fickle patriarchal authority, the serpent spirits have allegiance to a thin-skinned, hypersensitive female nature, with a formidable armory at their disposal.

The serpent spirits live in the earth, in the rock, and in the lakes and streams. Their usual form is snake-like. They are black, white or red.

They can take human form or shape-shift according to requirement. They guard the mineral wealth of the earth including rock and the soil itself.

Precious stones belong to them and the magical power of a coral or turquoise stone is determined as auspicious or inauspicious according to its guardian serpent spirit's satisfaction regarding the manner in which it was mined and the care that has been taken of it.

To mine iron or gold is to offend the serpent spirits and is equivalent to stealing from them, unless a pact is agreed upon and propitiation made.

The low status of iron-workers in traditional Tibet is due to their subordination to the serpent spirits.

Rock is also protected by them and they object to the movement of stones from one place to another, and, of course, the hewing of stone. Propitiation of the serpent spirits precedes any building activity.

Even to dig a hole in the ground is to risk offending them, and to plough the soil is to invade their domain and all agriculture is therefore dependant upon a working relationship with them.

Trees and plants are also protected by the serpent spirits.

Although any of the gods, demons and spirits can afflict human beings with disease by creating an imbalance within the psycho-organism through the element with which they are identified, or acting on the level of human consciousness which gives them their existence, the serpent spirits are the chief arbiters of human health.

This power is derived chiefly from their affinity to water. As guardians of springs and water courses they protect the flow and the purity of water.

In the cold Tibetan climate the danger from water-born intestinal disease is minimal compared to the peril on the Indian plains, but the pollution of water sources angers Tibetan serpent spirits no less than their Indian cousins.

Their ire afflicts those who fail in their hygiene. Serpent spirits also control the bag of leprosy and tuberculosis, and sores and itches are serpent-inflicted.

Since the body is ninety-eight percent water, they have special admission to the psycho-organism and are the cause of diseases of bodily water imbalance such as abscesses, ulcers, and swelling of the limbs and dehydration.

Diseases related to excessive indulgence are also caused by the serpent spirits.

The serpent spirits are propitiated with offering and herbal incense.

The female entity that can be conceived as the mistress of the legions of serpent spirits is the demoness (sinmo) who can be seen in the landscape.

The demoness of Central Tibet, for example, lies supine across the central provinces, embodying all hostile elemental powers.

This demoness combines the chaotic, relentlessly destructive power of the external environment with the savage bestiality of the internally latent female archetype.

Incarnate demonesses or rock-ogresses stalk the earth after human prey.

They are the original inhabitants of Tibet in Buddhist mythology.

The specifically female sky-goddesses called sky dancers (khandromas, dakinis) share this elementally malign nature and, like the mother goddesses (mamo), may relate to men and eat his flesh and afflict him through sexual relationship.

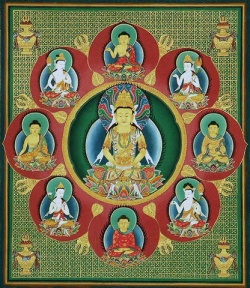

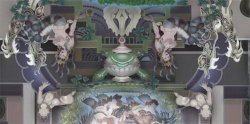

Mandala-Vision

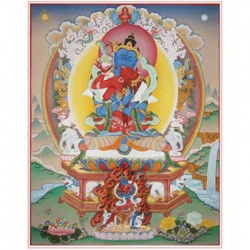

In the sphere of buddha-vision, where the nature of mind is understood as emptiness and space, the infrastructure of awareness is the mandala.

Appearances, such as the landscape, are still in their seemingly chaotic natural order, but within the perception that is a unity of outside and inside is the symmetrical, three-dimensional, mandala form.

Mandala-vision is awareness of the underlying purity and the perfect symmetry and harmony of every perception.

These natural mandalas, spontaneously in-born in every perception, are expressed in the symbolic terms of the tantric tradition as three-dimensional models or two-dimensional plans.

In those forms the aspiring yogi can visualize them, and through recognition of the reality which the symbols represent he can attain mandala-vision and buddha-vision.

The simplest of mandalas, the basis of all mandalas, is an empty circle.

The Tibetan word for mandala means 'centre-circumference' (kyilkhor).

The centre of the simple mandala circle represents a point instant of pure awareness of unbounded inner space that is emptiness (tongpanyi, shunyata), which cannot be conceived or expressed.

It is represented anthropomorphically as a naked blue Buddha, the Primordial Buddha.

This emptiness interpenetrates every level of awareness, providing the fluidity of perception and also the transcendent qualities of radiance and fullness that characterise every perception.

The fundamental circular mandala also represents an intuitive recognition of the basic building block of experiential reality, the empty nucleus of every moment of experience.

Thus, while it indicates the essential element of reality, it also structures 'uncreate', primal awareness in three-dimensional form.

Every form that arises in this mandala of mind is empty; all emptiness has form.

The mental generation of a mandala by the yogi is an exercise in structuring the apparent chaos of human experience. Visualisation and contemplation of a mandala automatically induces mental calm.

The simple mandala circle gives a frame to the contents of the mind giving an essential confining order to what has been unbounded chaos.

The empty space within the circumference of the circle evokes the emptiness of its content, the ultimate empty nature of reality.

The structure of a complex mandala indicates the essential elements of the mind and its levels of awareness in a point instant of sensory experience.

The complexities of imagery and symbol within a sophisticated mandala indicate the noumenal characteristics of the content of any given moment of experience.

This imagery and symbol is usually in the form of anthropomorphic figures - male and female buddha-deities.

In order to 'read' a mandala it is necessary to know the structure of the hierarchy of the pantheon and the meaning of the symbols that compose the individual deities.

The internal mandala, crucial to the practice of tantric yoga, describes in symbols the psycho-organism interacting with its sensory environment.

Implicit in this interaction are the five senses - seeing, hearing, tasting, touching and smelling;

the feeling tone that arises with every perception - positive, negative or neutral;

the emotional content of the perception: -

the thought that arises with it;

the impulse towards continued sensory activity generated by thought and emotion informing karmic proclivity; and finally the consciousness that greets every perception.

Formally, the mandala representing this complex fivefold moment of human experience consists of five circles - a central circle surrounded by four circles in the cardinal directions, all within the confining circle.

The five circles are represented anthropomorphically by Buddhas differentiated by colour and hand gesture.

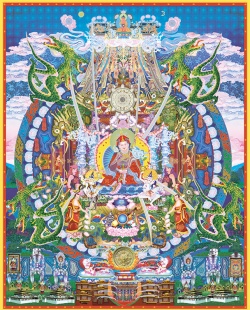

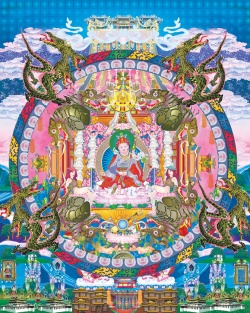

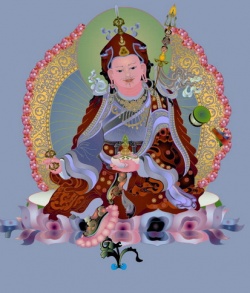

Guru Rimpoche's Glorious Copper-Coloured Mountain Paradise

Guru Rimpoche, the Precious Guru, whose personal name was Padmasambhava, was the Buddhist tantric sadhu and exorcist from the Swat valley in the ancient kingdom of Uddiyana, now a part of Pakistan, who was invited to Tibet in the eighth century to establish the tantric teaching.

His charismatic presence dominated the early period of propagation of Buddhism in Tibet, and after the Bon resurgence had worn itself out and the second period of intense dissemination began, he was envisioned as a Second Buddha of our era, and became an essential figure in the mythic vision of the Tibetan people.

His legend describes his departure from Tibet flying from the top of the Gungthang Pass, near the Pelku Tso lake, on the mythical white horse of the buddha-dharma carried by sky-dancing female Buddhas, or khandromas.

His destination was Ngayab Ling, an island in the ocean to the south-west of Dzambuling where his mission was to teach the cannibal-demon inhabitants the trans-formative path of the tantra.

His success in achieving that objective is described in terms of Zangdok Pelri, his Glorious Copper-coloured Mountain Paradise.

The Glorious Copper-coloured Mountain is an island-mountain in the cosmic ocean and the periphery of the island defines the circumference of a mandala.

Within it are the walls and four gates guarded by the Four Guardian Kings.

At the centre is a three-roofed pagoda temple, and between the gated mandala walls and the temple the community of initiates practices the teaching of Guru Rimpoche in a transformed environment.

On the ground floor of the temple Guru Rimpoche is enthroned surrounded by his Indian and Tibetan consorts, and lama and yogi exponents of his vision.

In the centre of the second floor is Chenrezik, the bodhisattva of compassion, and in the centre of the third floor is Wopakme (Amitabha).

The relationship between these three Buddhas is defined in Padmasambhava's birth legend.

Twenty-four years after the parinirvana of the Buddha Shakyamuni, the primordial Buddha of Boundless Light, Wopakme, conceived the thought of perfect enlightenment in the form of the great compassionate one,

Chenrezik, and from Chenrezik's heart, I, Padmasambhava, the Lotus Born Guru, was emanated as the syllable HRI, and I came like falling rain throughout the entire world in innumerable billions of forms to those who were ready to receive me. (Dowman 1973:74)

Or, as interpenetrating spheres of being, Wopakme is all-pervasive light and awareness;

Chenrezik is his pure and compassionate vision; and

Guru Rimpoche is the transforming illusion of the lama's sensory fields.

In the sky around the top of the temple float male and female sky dancers also practising the Guru's teaching.

The Glorious Copper-coloured Mountain is a far-away pure-land into which the devotee prays for rebirth so that his meditation practice can mature in his next lifetime in the presence of Guru Rimpoche.

It can also be an attainable state of meditation accomplishment in this lifetime and is experienced in actual sensory perception of the Tibetan environment.

The Copper-coloured Mountain Paradise, or more specifically its three-roofed pagoda temple, is sometimes replicated in the gompas of the Nyingma order such as the Lama Gompa near Bayi in Kongpo, at the Jiu gompa at Tso Mapham lake (Manasarovar),

at the Kuthang gompa in the Kyimolung hidden valley, and at Tathang and Dodrub Chode in Kham.

But at the Chimphu hermitage site a rocky crag, invested with several caves, is called Zangdok Pelri, and in its very lack of symmetry, and lack of formal similarity to the mandala icon,

the internal location of the vision and its dependence upon the meditative achievement of the yogis who live there is signifed.

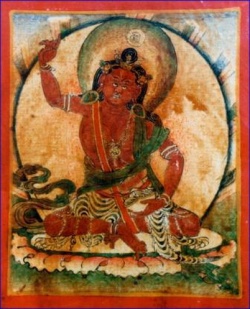

The Mother Tantra Vision

Buddha-vision is a unitary vision of outside and outside, a unification of the objective environment and landscape, and the subjective mind.

The pure-land mandalas and the mandalas of Shambhala and the Glorious Copper-coloured Mountain describe this vision in terms of a Buddha in his palace at the centre of a purified environment.

These are mandalas of form, outer mandalas.

On an inner plane, in the sphere of pure psychic vibration, buddha-vision can be described in terms of the focal points of energy in the subtle body of the transubstantiated yogi.

The tantras that develop this vision to its optimal extent are the mother-tantras (in distinction to the father-tantras), the tantras that take a female buddha deity as the principal of the mandala and develop the female aspect of the two-in-one union of tantric metaphysics.

The Demchok (Samvara), Kye Dorje (Hevajra) and Dorje Phakmo (Vajravarahi) tantras are the most popular of this type.

Here the subtle body is described in terms of psychic channels, energy flows and focal points of energy. In a simplified blueprint, the central channel runs from the perineum to the fontanelle.

Right and left channels branch off from the central channel below the navel and run parallel to it to the head and then emerge at the nostrils.

There are seven energy centres (chakras) on the central channel relating to the anus, the genitals, the solar plexus, the heart, the throat, the head and the fontanel.

Right and left channels join the central channel at the navel, heart, throat and head centers.

From the seven energy centres subsidiary channels branch off, and constantly bifurcating at minor focal points they penetrate to every extremity of the body - something like the nervous system.

There are various energy flows or 'winds' within these channels, but essentially, in the transformed body of the yogi the direction of flow, from the central channel into the right and left channels and into the capillary channels,

has been reversed, so that all movement is directed into, and up, the central channel, where the energy centres bloom like lotuses of enlightenment.

The reversal of energy flow is a metaphor for the process of unification of duality, which results in buddha-vision.

The energy centres, major and minor, though possessing a reference within the microcosmic subtle body, represent the union of inside and outside.

The subtle body and its focal points of energy are externalised into the landscape as the supine body of Dorje Neljorma (Vajra Yogini), the Khandroma, the essential female Buddha.

It is her body that lies across the entire Indian sub-continent, from Cape Comorin to the Himalayas, from Assam to Pakistan, and the major power places of the sub-continent give access to the energy centres of her body.

Twenty-four power places are divided into three mandalas of eight places pertaining to the Khandroma's body, speech and mind. The symmetry of these places exists only on the inner, visionary, plane.

Two of the original list of twenty-four are located in Tibet, at the great mountain power place of Kang Rimpoche (Kailash) and at Tretapuri, a power place not far from Kang Rimpoche.

But two other important locations were transposed to Tibet by yogis who themselves sanctified the great power places with which they were identified.

Devikota, originally in West Bengal, was re-identified with the great mountain of Tsari, with the hermitage called Lhamo Kharchen in Lhokha, and also with the lhakhang called Phawongkha near Lhasa.

Godavari, in South India, was re-identified with the great Labchi mountain.

These transpositions gave Tibetan yogis access to the Khandroma's energy down the centuries.

Most of the twenty-four power places were originally determined by their geomantic significance and are sacred to all peoples, regardless of their religious tradition.

Not only the places in the heart of India, but Kang Rimpoche and Tsari, which are also Bonpo power places, are sacred in the Hindu tradition.

The symbol that represents the goddess Devi, the yoni (vulva), and the symbol that represents Shiva Mahadeva, the lingam (phallus), are also found there.

This simply stresses the inchoate nature of the energy at these places and the importance of the vision of the individual yogi.

Historically, the twenty-four power places were first identified as places sacred to Shiva Mahadeva and Devi, his consor, and the Buddhist vision of the manner in which they were transformed, given below, is highly instructive.

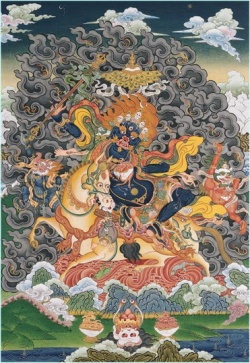

Towards the end of time, in the kaliyuga, when anger, lust and ignorance were rife, Shiva Mahadeva in his most terrific form, Ugra Bhairava, overwhelmed the earth and took up residence in the form of lingams in the twenty-four power places.

At the end of the kaliyuga, Dorjechang (Vajradhara), the primordial Buddha, resolved in his wisdom to subdue the terrifying gods who controlled the earth. While remaining established in imageless compassion,

he manifested as Buddha Heruka, and with even greater wrath than that embodied by Bhairava, in dancing posture he trampled Bhairava under foot and thereby Bhairava attained supreme bliss and complete realisation.

Buddha Heruka's emanations entered into the lingams that had been Bhairava's abodes and sanctifying them as themselves they dressed themselves in the form of Bhairava and his minions and used their ritual appurtenances as their own and transformed their rituals into the rituals of light and liberation.

Rudra

The parable of Rudra describes the subjection or transformation of the inner, divine, ego (Rudra or Bhairava) into an emanation of the Buddha's emptiness and compassion.

There was once a tantric Buddhist guru who taught that all experience was essentially pure as it arose spontaneously in the mind.

The Guru had two disciples who were friends.

The first, without following after the impulses that arose in his meditation realised the natural purity in the spontaneous rising and falling of moments of all experience and achieved the detachment of the Buddhas.

The second disciple left his Guru, and watching the nature of his experience in meditation he ran after the impulses that arose therein.

He built a brothel, gathered a gang of thugs and raided neighbouring villages, killing the men and abducting the women.

After some time the two friends met, and surprised by the nature of each other's tantric practice they sought out the Guru to seek his verdict.

The Guru praised his first disciple and condemned the second, whereupon the brothel owner, unable to bear the knowledge of his own error, unsheathed his sword and killed his Guru on the spot.

When he died, he was reborn successively as a scorpion, a jackal and other wretched forms of sentient life, until eventually he was reborn in the realm of the gods as Rudra.

Rudra was born with three heads and six arms, with fully grown fangs and talons.

His mother died at birth and the gods were so horrified with her offspring that they entombed him with her.

Rudra nurtured himself on her flesh and blood and when he gained his monstrous maturity he organised the ghosts, ghouls and cremation ground life into an army and sought to control the heavens, the earth and the underworld.

Meanwhile his friend had attained the Buddha's enlightenment and sought to subjugate him. He transformed himself into the Bodhisattva Chakna Dorje (Vajrapani) who in turn became the Heruka Tamdrin (Hayagriva), an emanation of Karunamaya, the bodhisattva of compassion.

He entered Rudra through his anus and possessed him with the realisation of emptiness and compassion.

Whereupon Rudra expressed his disillusion and conversion and offered himself as the throne of Heruka at the twenty-four power places.

Buddhist masters intent upon subduing gross forms of ego, attachment to objects of passion,

and transforming passion into its pure nature, thereafter took the outer form of Rudra, with his bone ornaments, tiger-skin skirt, human and elephant skin shawls, and so on, the form of the wrathful deities of Buddhist tantra.

This parable is not only important in the understanding of the relationship between Buddhist and Hindu tantra and of the nature of the seemingly demonic forms of the buddha-deities, but explains the conversion of the great mountain power places of the Himalayan range from Hindu to Buddhist.

Kang Rimpoche, Labchi and Tsari were the seats of Mahadeva and his consort Uma long before the advent of tantric Buddhism.

Perceived as giant lingams by the Hindus, they were identified by Buddhist yogis as the buddha-deity Demchok (Samvara) in sexual union with his Khandroma consort Dorje Phakmo (Vajravarahi).

The subtle body of the Khandroma is represented at Kang Rimpoche by the three main valleys, Darlung (Flag Valley), Lhalung (Divine Valley) and Dzonglung (Fortress Valley), which are envisioned as the central, left and right channels of the subtle body.

The body of the Khandroma can also be found in many places in the sacred landscape of Tibet where the Buddhist tradition has no Hindu antecedents. One of her principal places of residence is Beyul Padma Ko, the Hidden Land Lotus-form, in south-eastern Tibet

At Kangri Thokar, a hermitage site to the east of the Kyichu river south-west of Lhasa, she lies supine as the ridge on which the caves and hermitages are located.

Two springs generating milky water mark her breasts; the Shukseb nunnery is on her left knee; and her vulva is the source of the major stream feeding the northern side of the ridge.

Again, the Drikung sky-burial site, or rather the round field of stones where corpses are dismembered, is identified as her navel while her entire body is to be found in the landscape of the Drikung region.

Motivation of the Lay Pilgrim

Realised yogis, though they may appear as beggars, and the high lamas, though they may appear as glorified maniquins, are on pilgrimage with intent to serve the Buddhist teaching and all sentient beings.

What of the ordinary lay pilgrim of today, who is, perhaps, a Communist functionary, or an illiterate nomad from the plateau?

Firstly, if he is aware of the rudiments of the Buddhist doctrine, his intention is to attain merit or to gain some specific spiritual advantage.

Secondly, he has travelled to power places to increase his luck or for some mundane boon.

The merit that he seeks in devotional activity, and pilgrimage in particular, is a peculiarly Buddhist concept.

There is no precise equivalent of the Tibetan word sonam in English.

Sometimes it is simply translated as 'virtue', but there are better words in the Tibetan language for virtue.

Merit is the product of positive or virtuous activity.

The karmic effect of a virtuous action is to reinforce the tendency to repeat that action in the future; merit has this same inherent reproductive propensity.

The feeling that should arise in the wake of a virtuous action is a pleasurable glow of self-satisfaction; merit has this same feeling tone.

But merit is also quantifiable, and this is where the concept becomes strained.

As something distinct from the action that generates it, it accumulates like savings in an account in the karmic bank.

The product of virtuous activity is credited to the account, and negative or vicious activity results in a debit.

The ten chief meritorious actions are restraint from killing, thieving and inappropriate sexual activity;

refraining from lying, worthless chatter, cursing, and sowing discord; and suppression of covetousness, malice, and opinionatedness. Committing such activity creates demerit.

All kinds of devotional exercise create merit, especially offerings to the Buddha, the teaching and the community. Pilgrimage is a major merit generator.

Merit is invested primarily to insure a better rebirth.

At death the quantity of merit in the karmic bank determines the mode of rebirth - the higher the balance the better the rebirth.

A substantial balance guarantees a rebirth in the upper realms of the gods, the jealous gods or the human realm.

A negative balance results in a low rebirth, in the realms of the animals, the hungry ghosts or the denizens of hell.

A large store of merit at death is the result of a lifetime of prudent and careful living.

For as soon as merit has been generated, the temptation arises to exchange it for a consumer product - a mundane boon, a guarantee of certain success in any enterprise, financial, sexual or social.

Perform a meritorious action, such as an offering to a Buddha, or, on a larger scale, building a chorten, and immediately there is bundle of merit to exchange for some advantage.

Pilgrimage automatically produces merit - and large quantities of it.

The more potent the power place destination the greater the merit accumulated.

The great sacred mountains, such as Kang Rimpoche (Kailash), Labchi and Tsari, are the most powerful merit generators. Just the intention to make pilgrimage generates merit, and when even a first step is made towards a power place, then the meter measuring the merit begins to run.

Circumambulation, one of the main devotional activities on pilgrimage is a major source of merit:

The benefits [or merit) for anyone who takes a step with the intention of performing circumambulation around a reliquary shrine of the Buddha, with faith in mind, are as great as making a donation of one hundred thousand ounces of gold. (Huber 1995:28)

A factor of seven hundred million is added to the merit generated by a single circumambulation of Bonri mountain.

The year and month of the pilgrimage also effects the quantity of merit produced.

If that circumambulation is performed in the horse, sheep, bird or monkey months the factor is 1.3 billion.

Even adventitious meritorious actions on the Bonri pilgrimage - saving the life of an animal for example - result in an automatic ten thousand-fold increase in the merit accumulated.

Likewise, 'whatever sins or demerits you commit will become as vast as Mount Meru or the Cosmic ocean.'

Evidently, with these vast amounts of merit in the offing, major changes to the pilgrim's habitual state of consciousness and his karmic patterning are possible.

There is seemingly a thresh-hold in the accumulation of merit above which transcendence is achieved along with the Buddha's enlightenment or liberation from the round of rebirth, the wheel of life.

In the doctrinal formulation, it is required that both merit and meditative insight into the nature of reality are optimised before this liberation is accomplished.

The tradition, particularly in the guide books to the power places, is quite explicit that merit is optimised by pilgrimage to the great sacred places,

and in the promise of ultimate spiritual attainment there is the assumption that insight into the nature of reality as emptiness and pure awareness is also increased to the point of a radical change in the nature of consciousness,

a metanoia that unalterably changes the way of vision and purpose in life.

As many pilgrims will affirm, awareness is involuntarily heightened at pilgrimage destinations, the causes of which will be examined below.

So, the guide book to Kang Rimpoche, quoting Guru Rimpoche, assures the pilgrim that,

Whoever visits Kang Rimpoche, the omphalos of the world, will achieve liberation within three lives.

Whoever circumambulates Tso Mapham lake with sincere faith will spontaneously attain buddhahood. (Ramble 1995:98)

Or, if the factors of the ultimate equation are not quite complete, then the 'doors of the six realms will be closed' to the pilgrim after death. At the end of the intermediate state between death and rebirth, if the transient principle of consciousness has remained in fearless equilibrium, then it will resist the beckoning lights of the wombs of rebirth into the upper and lower realms and find itself in the pure-land of one of the Five Buddhas or in the Copper-coloured Mountain, Pure-land of Guru Rimpoche, in Shambhala, or in the Land of the Orgyen Khandromas

If the merit that is accumulated is not quite sufficient to produce buddhahood, or liberation from the wheel of rebirth, it may be enough to induce magica powers or one of the super-sensory insights.

The abilities of flying in the sky, walking through rock, or knowledge of the language of animals and birds, reading minds and so on, are powers that may be attained through a surfeit of merit and heightened awareness, particularly at the power places where the sky dancers dwell.

It is they who bestow such powers.

The guide book to Tsari promises that if you make any offering to the Buddhas at that mountain power place, which is a gathering place of the sky dancers, you will achieve special powers.

Likewise, if you meditate only for a short time without moving on the rock called Amoliga at the Bon mountain of Kongpo Bonri, you will enter samadhi which will blaze up in you like a fire, and the memory of your past lives will be awakened.

The pilgrim with the right intention will, at least, and automatically be cleansed of sin.

Sin (dikpa) may be defined as ignorant acts of thought, word or deed, acts only partially understood, because of lack of awareness, or stupidity, acts producing demerit.

Sin can be acts conflicting with moral standards or codes imposed by society by the lama or by oneself - in the conflict arises guilt, a sense of inadequacy in the face of this conflict.

Whatever the cause, demerit is the result, together with the karmic propensity to repeat the sinful activity.

The dualistic ignorance and the conflict is resolved by attaining a holistic vision or by reaching the crux of the duality.

Absolution is attained there.

The method by which this crux is reached varies according to the spiritual maturity of the sinner.

The lama's blessing may be sufficient.

Meditative absorption can purify and absolve.

Ritual confession in meditative concentration is the monk's method of purification.

If the guilt is particularly intractable, pilgrimage is a last resort.

Pilgrimage purges the mind of the demerit and the propensity to repeat the action. Absolution is obtained at the power place.

Because of the blessings bestowed by the three great knowledge holders, just by visiting that holy place [[[Bonri]]) your impurities will be purged. It is sufficient merely to set foot upon that flowery place...

If you drink from this water and wash in it, your defiled sinful condition will immediately be purified and you will receive spiritual benefit and immeasurable wisdom. (Ramble ms)

Whoever drinks from the blue lake of Tso Mapham will purge the sins of his successive lives. (Ramble ms)

The most intractable of sins are the five boundless or inexpiable sins.

They are the sins of killing one's father or mother or a lama, creating a schism in the religious community, and maliciously causing a Buddha to bleed.

With such guilt on one's conscience, at death, without any opportunity for release in the intermediate state between death and rebirth, the bardo, the sinner falls immediately into the deepest of hells.

It is further evidence of the miraculous illuminating quality of a power place and the immense store of merit accessible on pilgrimage that even the most stubborn stains of these so-called inexpiable sins on the karmic flow can be eradicated.

Circumambulation of Kang Rimpoche will certainly expiate these sins, promises the guide book.

There are also specific power place destinations that guarantee absolution for particular sins. Chorten Nyima, near the Sikkim border, for instance, is the destination of those who must expiate the sin of incest.

The power of water in the sacred lakes and springs issuing from the mountain power places to purify sin is mentioned above.

The virtue of bathing in these waters is seldom mentioned, since bathing is traditionally taboo in Tibetan society.

The reluctance to bathe is based on a valid concern for health; the veneer of fat and grease covering the body is necessary to retain heat in the extreme cold and the water of the body in the extreme heat.

Loss of body heat causes disease; loss of water through perspiration causes dehydration.

Perhaps the ritual of bathing for purification is derived from the Hindus, in whose culture and climate bathing is a rite of worship and crucial to good health.

At least drinking the holy water is offered as an alternative here, but there is no indication that bathing and rebirth in the paradise of sensually absorbed sky dancers has any specific connection:

'Those drinking or bathing in the waters of Tso Mapham lake will go to the sky dancers paradise of great bliss.'

The waters also have the power to cure disease, and pilgrimage is frequently undertaken to this end:

To the south of Bonri, there flow nine streams which heal leprosy, sores, deafness and the hundred and four type of ailment. Nearby, there is a stream of purifying nectar which cures dropsy and leprosy. (Ramble 1995:53)

The attainment of liberation from the wheel of rebirth immediately, at death, or in three lifetimes, accomplishment of magical powers, rebirth in a buddhafield, purging of sin and negative karma,

and even healing, are all benefits that accrue to the devout lay pilgrim whose intention or prayer it is.

Undoubtedly pilgrimage benefits those best equipped to receive its effects, pilgrims with a developed meditation ability, an unfolded responsiveness to the inner world, and a receptive vision.

But what proportion of Tibetan pilgrims today have this karma?

It may be that the ratio of the spiritually mature and immature in any given culture remains more or less the same regardless of the political or social regime.

Perhaps in times of adversity - and Tibet has rarely experienced such misfortune as in the last thirty years - faith and devotion, and craving for spiritual solace, increases.

It is difficult to register to what extent the radical diminution of institutional religious education has affected the aspiration of the people, and it is certain that the Tibetans have had less of that input in the last generation than any time in the last thousand years.

In Tibet, as in the whole of Asia, there is evidently an increasing trend towards fascination by technology and the material culture of the Western world, and the materialistic propaganda of the Tibetans' political masters,

the Chinese Communists, certainly has made a deep impression upon their minds.

What is certain, however, is that the motivation of a large proportion of Tibetan pilgrims is mundane and has always been so.

The pilgrim wants his yak herd to increase, or more specifically he wants Drolma, his yak, to calve this season. He wants promotion within the commune so that his pasture rights are assured.

He needs the price of butter offered by the dairy collective to increase so that he has the extra cash in his pocket to buy a radio.

He, and his daughter, need protection from the Chinese cadre whose face he blackened and who wants him in jail.

He has that little bronze Buddha that his father gave him and for which the Khampa trader offered him a hundred qwai, but maybe, tomorrow, two.

He wants the girl who is on the same pilgrim truck. He wants the weather to change.

He is a Buddhist and he will recite the MANI PADMA mantra, and the refuge in the Buddha, and make offerings to the lamas and the Buddhas, to increase his merit on this pilgrimage, and perhaps the merit will be sufficient to obtain his goal.

But he has no knowledge of the arcane doctrines of tantra or the mysteries of the lamas who are like gods to him, and while he lives in awe and fear of the great buddha-deities and protectors, his faith is focused more on the local gods,

the mountain gods, the elemental spirits, the spirits with whom he feels at home, and to whom his father prayed and devoutly made the calendar rituals.

The lamas who did not flee to India when the Chinese suppression began were murdered or imprisoned. Where was their vaunted power of protection then?

They could not save his uncle from death in the labour camp building the great road, or his grandmother from death by starvation.

The gods of the fields and the cattle, the fierce gods and goddesses who lived on the mountains and their minions of the rocks, remained unchanged during the hard times,

and although outward ritual was forbidden prayers to them still seemed to be answered and his luck has not been so bad in the last few years. Yes, it all comes down to luck.

The concept of luck is much older than that of karma, which came from the South, from India, with the Buddhist missionaries during the empire period.

Luck or tashi was what the shaman priests were principally concerned with inducing and what had been the preoccupation of the nomads and villagers forever.

Luck is the gift of the gods and spirits, who are not influenced by virtuous conduct or social morality.

They require recognition through offering and ritual - even token notice is enough - and through such recognition a balance is created - an ecological balance and an equilibrium of man within his environment.

If recognition is withheld, offering and ritual omitted, then their displeasure, their wrath, will be revealed as a disequilibrium of man and nature and ill luck will ensue.

Disease is the chief symptom of chaos in the three realms - the heavens, the earth and beneath the ground - disease of men and cattle.

The gods' anger shows in unseasonable and inclement weather - hail, sandstorm, or drought - causing destruction to crops and cattle.

In personal affairs ill-luck will attend sexual liaisons, business enterprises, trade, and, of course, dice.

While the doctrine of karma is easy to grasp in theory, it is difficult to see how the acts of the gods are determined by personal moral behaviour, and impossible to know how conduct in past lives is influencing the present directly.

Luck and ill luck, on the other hand, are the impersonal dispensation of the gods and spirits who may be influenced by ritual offerings but in general are above the petty activities of men.

A better rebirth in the next lifetime is, of course, much to be desired, but rebirth is an abstract concept, far away, and, anyhow, can mere human beings affect the designs of the gods?

Luck, on the contrary, is tsampa and butter tea and good health;

it is sexual satisfaction and one in the eye for the enemy; it is money in the pocket and a transistor radio on the shelf; it is a healthy thriving herd of yaks and a good crop of barley.

So, the ordinary pilgrim to the power places will be seeking to re-establish or secure a line of communication with the gods and spirits of the place, to attain the balance that will give him their favour, to increase his prosperity and his luck.

There is another issue that looms large in the minds of many contemporary Tibetan pilgrims, regardless of whether their aspiration is spiritual or mundane. This is the matter of Tibet's political status.

There is only a minuscule proportion of Tibetans that does not find the Chinese occupation burdensome and wish for relief from it.

The notion of Tibetan Freedom, 'Bokyi rangtsen', is now universally known in Tibet, and although few Tibetans will be aware of the geopolitical realities, they devoutly wish for a change.

On pilgrimage, at the power places, this will be articulated as a prayer for the retreat of the Chinese into their own lands, or a prayer for the long life of Yishi Norbu, the Dalai Lama, and for his return to the Potala in Lhasa as the head of state.

Even if the wish for independence is not explicitly verbalised, it will certainly be implicit in the pilgrim's prayers to Chenrezik, the protector of the Land of the Snows.

It will also be implicit in prayers to the fierce guardians of the tradition, to the mountain gods and their retinues who are bound to protect Tibet, its inhabitants and the Buddhist teaching.

The Pilgrim's Devotional Practices

Involuntarily heightened awareness, the psychedelic aspect of the experience of pilgrimage, can be seen as the affect of automatic, reflexive, purification.

Through a process of purging and repurging body, speech and mind, heightened awareness is induced along with its symptoms - euphoria, vision of the landscape transformed, internal apocalyptic vision, a sense of weightlessness and slow-motion,

and a singular gaiety and bonhomie - none of which has any significance beyond the gnostic awareness that gives rise to it.

The body is automatically purified by the exertion to the point of exhaustion that is inescapable at most power places.

The Western pilgrim's constitution is capable of less exertion than the Tibetan's, but the affect is the same. Fatigue purges the body and renders the psycho-organism more susceptible to the genii of the power place.

Physical exposure to extremes of elemental weather - the sun, the snow, the wind, at high altitudes, has a similar purging effect.

If just getting to the place does not induce the requisite exhaustion, then prostration and circumambulation certainly will. Speech and vibration is purified by external sound, rushing water or soughing wind,

which may become an object of meditation, and also by incessant recitation of mantra and prayer.

Once a mantra is set in orbit around an energy center, a chakra, it will spin automatically producing the sound that purifies psychic energy, its subtle vibration and articulate speech.

And the mind, through concentration upon an object of meditation, a mantra perhaps, or its accompanying visualisation, is also naturally purified.

The blessings of the lama, the power place and power objects also naturally purify body, speech and mind.

The mind can be spontaneously reconditioned to the Buddha's reality by synchronistic circumstances that leapfrog the process of karma, and pilgrimage appears to quicken such adventitious conjunctions.

But in the relative world nothing whatsoever can be accomplished without faith, and of this the pilgrim has abundance.

Faith is the belief, confidence, and then conviction, that heartfelt aspiration, sublime or ridiculous, can be realised; no faith, no realisation. So faith is the kernel of the aspiration and nothing can happen without it.

In those who lack faith

Nothing positive will grow,

Just as from a burnt seed

No shoots will sprout. (Ricard 1994:172)

Pilgrimage itself is a demonstration of faith and so are the devotional exercises that all pilgrims practise at the power places.

Pilgrims practise at the power places

These are prostration, circumambulation, offering, prayer and recitation of mantra.

The key to the transformation of the landscape from an elementally savage scenario, or a desolate mountain desert topography, into a mandala vision, is faith:

People with pure karma can see these outer places of Heruka as pure lands;

those with impure karma see them as ordinary geographical locations...

When you walk around places such as Bonri in Kongpo, since they are receptacles that have been blessed by an enlightened teacher, you should imagine that, while performing your circuit, you are walking round the enlightened one.

It is not merely a matter of making prostrations and circumambulations while bearing in mind the local genii, territorial gods and swastika of these places: whatever sacred receptacle you visit you should consider that it is this or that enlightened one and be reverent and rejoice.

This is what is important. (Ramble 1995:55)

It is certainly impossible to enter the mythic realm, whether the objective is to attain buddhahood or to manipulate spiritual phenomena for one's own advantage, in a state of rampant egoism.

It is impossible to force an entry into the visionary realm.

There is no possible purpose of pilgrimage that does not demand certain loss of ego.

The Buddhist definition of ego loss implies a diminution of the sense of 'I', of a separate independent 'island' person, and a corresponding increase of a consciousness of the organic totality, of the interdependence of all the factors of existence, inner and outer.

Total loss of the sense of a substantial self in both oneself and others and simultaneous arising of the knowledge that nothing exists outside there independent of the mind that perceives it, is a definition of buddhahood.

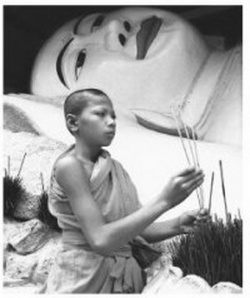

Much of yoga and meditation technique has loss of ego as its aim and all tantric meditation liturgies begin with the basic technique of ego reduction - this is homage and prostration.

The pilgrim makes verbal homage and physical prostration whenever suitable objects of obeisance appear. Indeed, the opportunity that pilgrimage offers for prostration is one of its most potent blessings.

Homage and Prostration

The form of verbal homage to the higher power, the noumenal reality of the visionary realm, may be one of the time-honoured sanskrit formulae: Namo Buddhaya, Namo Avalokiteshvara, etc: or it may be in the Buddhist formula of refuge (see below).

The attitude of obeisance is physically expressed in the namaste mudra, palms pressed together at the heart centre.

It may be useful to remember the popular Indian interpretation of this gesture - 'I bow to the divine within', whether it is a person, an image, a rock or a mountain that is addressed.

But the sentiment of obeisance is better expressed physically as prostration, lost in India, but seen everywhere in Tibetan devotion and pilgrimage.

With palms together at the heart centre, first touching the forehead, the throat and again the heart, the common half-prostration involves touching the ground with seven points of bodily contact - toes, knees, palms and forehead.

The full prostration consists of an extension of this so that the arms are outstretched the palms touching, and the body lying prone full length on the ground.

Obeisance and prostration are performed before symbols of buddha-body, speech and mind.

An image of the Buddha is the best representation of his body, but the devotee on pilgrimage in the sacred landscape finds symbols of his body in mountains and rocks.

Books of scripture represent buddha-speech, but single mystic syllables carved into the rock symbolise an entire canon of scripture.

The chorten represents the buddha-mind and votive chortens are to be found at most pilgrimage destinations.

The Lama himself is an embodiment of buddha-body, speech and mind, and provides the superior object of prostration.

To the mindstate of devotion and receptivity that is the immediate effect of prostration, the lama can add his blessings.

The object of obeisance can also be visualised.

For pilgrims who perform full-length prostrations counting their out-stretched body-lengths, from toe to finger tip, from their home to their pilgrimage destination - the Lhasa Jokhang for instance - their mental yoga is to visualise the Buddha or a buddha-deity in front of them.

The same applies to devotees who prostrate around a khorra circuit.

The superiority of full-length prostration over five pointed prostration is explained by the Fourteenth Dalai Lama:

When you walk a circular pilgrimage route, such as the one around Mount Kailash, your feet touch the earth with big paces between them, but when you prostrate, your whole body connects with the sacred ground to close the circle. (Dalai Lama 1990:132)

Offering

In a mindstate of devotion and humility the threshold of the visionary realm is lowered sufficient for access.

Indeed, it may have already put the devotee in an intense visionary state.

The ritual procedure now required for a dynamic interactive relationship with the noumenal forces of this realm supports and develops the process of ego-loss already begun.

This ritual gesture required here is offering (chod; puja).

The full ritual of offering - seven outer sensory objects and the inner experience of those sensory impulses - is required only if a simple token gesture is ineffective.

The image of a child making a gift of a flower provides the paradigm of such a token offering.

The gift is offered in innocence; it has no intrinsic value; there is no thought of advantage. The result is a communicative bond between the giver and the recipient.

When the devotee makes an offering to the noumenal power of a power place, if supportive factors of the devotee's attitude are sufficiently strong then the bond is an integral union.

At least, a bond is formed between them which provides a conduit for a two-way flow.

The offering of a white flaxen scarf (katak), is the conventional offering made to a lama as a token of respect, but the katak is also offered to an image, or to the presence of a Buddha or buddha-deity in an aspect of the landscape.

Kataks piled on the lap of an image, or on top of a shrine or a rock, are signs of pilgrims' devotion.

A butter lamp is the symbolic offering of light, both sunlight and the inner light of vision.

Pilgrims and devotees at the great gompas and temples will walk from shrine to shrine carrying a kettle of melted butter or oil,

pouring a ladle full of liquid into each of the giant butter lamps that are never allowed to run dry.

Or the offering of a butter lamp may be facilitated by the priests of the place upon a small payment.

Electric lights in front of images on the altars have now begun to augment the butter lamps as permanent offerings of light.

The offering of incense providing sweet smelling fragrance for the pleasure of the divine presence, visible or invisible, together with the medicinal affect of many kinds of Tibetan incense gives pleasure to the deity.

Flowers give pleasure to the eye and the nose of the deity.

Food or drink offered to the deity pleases his sense of taste, and a part of the offering returned to the giver contains the deity's blessing.

Tsampa, roasted barley flour, the staple of Tibetan diet, is the usual offering of food, though rice is beginning to replace it.

Now that paper money offering has become common in Tibetan society it is very frequently given as an offering.

Money represents not so much the currency of mammon as a precious item difficult to come by and hard to part with, and so more meaningful as an offering.

The final recipient of all offerings that have some intrinsic value or use are, of course, the priests, the monks or the lay officiant at the shrine, and money is best received by them.

The final destination of the offering, however, is of little concern to the pilgrim.

The function of the offering is to create a relationship with the divine presence, and the ritual giving itself is the point of the exercise.

Yet waste in the form of offerings is less evident at Tibetan shrines than at many Indian power places, for example, where a less hard-headed and less practical attitude prevails.

Another category of offerings to the Buddhas is personal effects.

Pilgrims will leave strands of hair, or indeed the complete cropping of the head, from the living or the dead.

A piece of clothing, a shirt, a sock or an old shoe will do. A hair band or a safety pin that has been in touch with the body will serve the purpose.

The intention of such offering is to leave tangible evidence of the pilgrim's presence in the place to remind the deity of the giver's prayer, particularly when he is passing through the bardo between dying and rebirth.

Wherever there is an altar - in a domestic shrine-room, in a gompa, in a hermitage or cave - a formal ritual of offering is performed as one of the first actions after rising from the bed.

The object of the offering is the Three Jewels - the Buddha, his teaching (dharma) and the community of practitioners (sangha).

The tantric practitioner will also have the Three Roots in mind - the lama, the khandroma and the yidam.

A single buddha-image can embody all of these. If there is no image or representation of a Buddha then a buddha-recipient is visualised.

The symbolic offering is made in the form of water, preferably water brought from a power place, poured into seven bowls.

The first is water for the Buddha to drink,

the second is for washing his hands and feet,

the third represents flowers to adorn his head or hair,

the fourth represents incense to please his sense of smell,

the fifth represents a butter lamp to please his eyes,

the sixth represents perfumed water to sprinkle on his body,

the seventh represents food to please his sense of taste.

Sometimes an eighth is added to represent music to please his ears.

The bowls are drained and stacked in the evening in readiness for the morning rite.

On pilgrimage, perhaps the most common form of offering is the offering of perfumed smoke or sang.

Sometimes a raised hearth built into a chimney is provided for this purpose, such as those on the Barkor in the four directions of the Lhasa Jokhang.

If there is no ritual hearth, then the offering can be burned in the open.

Leaves and twigs of fragrant shrubs such as juniper and rhododendron are offerings most favoured by the offering's recipients.

But what is crucial is that perfumed smoke should rise into the sky and be received by the Buddhas and their guardian retinues.

Prayers are offered to the Three Jewels, the bodhisattvas and the buddha-deities, but the recipients uppermost in the prayer of the layman are the guardian protectors such as the mountain gods and the protectors of the tradition and their retinues of minor spirits to whom some karmic debt is due.

Offering, or ritual giving, is generally the most vital purpose of the pilgrim at the power place. As the single most effective ritual gesture that creates the intimacy with the divine presence, offering is the pre-condition for any advantage to the pilgrim. It may be that he has no knowledge of, interest in, or capacity for visionary experience or buddhahood in this lifetime, but the bond with noumenal energy is the medium through which any relative spiritual or mundane benefit is to be accrued.

Offering is made as obeisance and as thanksgiving;

as a token requiring reciprocal response from the deity; as propitiation averting hostile influences;

as a means of accumulating merit towards a better rebirth.

The meaning of the offering is determined by the relationship between the giver and the recipient.

The Sacred Person

If buddha-vision is perfected then everyone you meet on your pilgrimage is perceived as a sacred person.

But the tradition promotes specific roles played by specially trained individuals who through empowerment, devotion and meditation can then perform the ritual function of the sacred person.

This highly trained person is the lama.

The lama is a teacher who through actions of body, speech and mind demonstrates the Buddha's teaching.

He may appear as a tulku, a monk, a yogi, a scholar, a wandering ngakpa magician or in a number of other shapes.

For the pilgrim he is the sacred person who is to be worshipped.

He may act as a mirror to the worshipper.

When in the devotee's perception he appears as a god, then he demonstrates a divine apparition;

when he is a magician he performs magic, like healing or telling the future;

when he is a Buddha he may preach or show some samadhi.

In these ways the sacred person gives the Buddha's blessings (jinlab) and, therefore, is considered with greater respect and devotion than the Three Jewels - Buddha, his teaching and the bodhisattva community.

The pilgrim gives prostration, offerings and prayer to the lama at the power place and receives blessings from him.

The tulku has the most exalted role. He is a Buddha incarnate.

A particularly charmed and talented child is recognised at a very early age as one of a succession of rebirths, and in a hot-house climate of monastic education is inculcated with the skilful means of the tantric tradition,

so that he knows nothing else, and exemplifies the spiritual ideal of tantric Buddhism.

At least that is how it frequently happened in the old days, when the cultural tradition was intact, when Tibet was an island society in Central Asia insulated not only from Western cultural influence but also from the Indian and the Chinese spheres,

when each gompa was a law unto itself, and daily life unravelled as a long ritual act, so that the tulku's conditioning over twenty or thirty years was given full scope to potentiate.

Perhaps that, too, is an ideal abstraction, but the power of belief actualises the concept, and there is no doubt that the Tibetan people believed, and still believe, in the reality of their buddha-tulkus much as we believe in the stardom of a movie idol, or, come to that, the inflexibility of steel.

The tulku was the spiritual authority in the gompa. A large gompa would have several tulkus.

Because they were also the political authority and the mainstay of the lamaist religion, they were most harshly treated by the Chinese Communists and formed a disproportionately large proportion of the exiles and also of the section of the Tibetan community systematically exterminated.

Some remained, but it is uncommon these days to find a tulku resident in a gompa; usually an abbot will preside.

At the cave or hermitage site the lama will probably be present as a yogi.

The hermit-meditator is tolerated by the present regime, presumably because he represents no political threat.

If he is good enough at his job he will be recognised as a self-created tulku and perhaps begin a line of reincarnations.

In the Nyingma tradition of revelation, such a yogi is an emanation of Guru Rimpoche, or put in another way, Guru Rimpoche himself.

As such, he has the omniscient awareness and the spiritual powers of Guru Rimpoche and possesses an aura of magical transformation.

The Tibetan word for blessing (jinlab) means 'wave of grace', and it is experienced as a hit of compassion and benevolence or even a psychedelic high.

It infuses the awareness of its recipient 'just as red dye saturates white cloth'.

The blessings bestowed by the sacred person, whether he is a tulku, a yogi, a monk or a ngakpa magician, do not differ in quality from the blessings obtained from power objects or from the rapport with a buddha-entity in worship.

But the sacred person combines the blessing of buddha-body, speech and mind and is easily accessible and has made a vow to serve all sentient beings. Transmission of blessings is one of his primary functions.

For this reason the transformed landscape and power objects are secondary to the lama as the focus of pilgrimage. As the primary agent of blessing bestowal he is the spiritual heart of a power place.

His blessing may be transmitted mind to mind, through the medium of a gesture or word, or by the touch of a hand or a power object.

It may also be bestowed in a knotted protection cord (sungdu) to be worn around the neck to ward off negative influences, or in an amulet in the form of small square flat bag containing a yantra of some kind also to be worn around the neck.

Any sacred substances bestowed upon the pilgrim by the sacred person is endowed with the extra potency of his blessing.

Power Places

Power places are the destination of pilgrims, and the sacred ambience of the place, its noumenal energy and the pilgrim's relationship to it, is sufficient to fulfil the pilgrim wishes.

'Power place' translates the Tibetan word ne, or nechen, which can also be rendered 'sacred' or 'holy place'.

The most momentous power places are the great sacred mountains and the lakes in their proximity, and cover, therefore, large areas, sometimes hundreds of square miles.

Within these areas the loci of power are the caves, particular peaks and rocks, springs and confluences, sky-burial sites, any of which, in any location may be power places.

Sometimes the natural features have been modified by man and the power place has become inseparable from the structure built at the place - hermitage, gompa, lhakhang, chorten.

Regardless of what has been built there, every power place gains its significance primarily from its geomantic location. Secondarily, it is consecrated by divine or human activity.

Geomancy is divination of the landscape.

The most common form of geomancy practised in Europe is dowsing, divination of subterranean water courses.

The Chinese have developed the art (or is it a science?) of geomancy far beyond any other culture.

fengshui, literally, means 'wind-water' - 'wind you cannot comprehend and water you cannot grasp'.

More specifically it is knowledge of the relationship between topography, water courses, natural chi and human modification of the landscape.

In practice, fengshui is used to discover a suitable place for building a structure and its ideal alignment.

Every new Chinese building in Hong Kong is sited according to the principles of fengshui.

Although Tibet received much of its mystic science and art from China, particulary and medicine and astrology, of which geomancy is a part, the developed art of fengshui seems never to have been transmitted to Tibet.

Geomancy in Tibet has to be defined in less sophisticated terms than fengshui:

it is more the art of divining the place of perfect harmony of the elements in the landscape, or in a more modest definition, identifying auspicious geomantic features in the landscape and locating power places.

This function is performed by yogis with visionary insight into the unitary relationship of mind and landscape.

Where the sky meets the earth at the top of a mountain or a hill is a power place. Kang Rimpoche (Kailash), Labchi, Tsari, Nyangchen Thanglha, Bonri, Kawa Karpo and Amnye Machen are some of these most sacred mountains.

Every valley has a mountain power-place in proximity.

Where the earth, sky and water are conjunct at a lake is a power place.

Tso Mapham (Manasarovar), Yamdrok Tso, Lamo Latso, Namtso and Tso Ngon (Kokonor) lakes are such lake power places.

Where a major river rises is a power place, like the springs of the four great rivers in the four directions of Kang Rimpoche.

Where two rivers meet is a power place, like the confluences of the Yarlung Tsangpo and the Kyichu, and the Tsangpo and the Nyangchu, and the river confluence at Labchi.

Where fire and water are mixed at a [[hot spring is a power place, like the hot springs of Terdrom and Tretapuri, and the flames on the water at Chumi Gyatsa (Muktinath).

A particular conjunction of space and rock provided by a cave may become a power place. A mountain pass is a power place providing an altar below a mountain peak.

Certainly there are many places in Tibet that are power places by geomantic definition, but unless they have been consecrated by tradition they lack the association with buddha-mind that endows them with particular sanctity.

When both geomantic and human factors are optimised the result will be a great power place, a nechen.

Sometimes, however, the geomantic power place will lack any human activity - Tibetan Buddhists, unlike the Taoist Chinese and the Bonpos, do not generally climb mountain peaks.

To the contrary sometimes a place most sacred to a religious order will be devoid of visible geomantic features - the birthplace of a saint, or the location of a gompa.

Power places are residences of a buddha-deity, a god or spirit.

But identification of such divine abodes imply application of a human mind. Recognition of a geomantically auspicious location and the noumenal energy that resides there is the work of a yogi or adept.

The identification is confirmed by the sage's continued presence there, his evocation, or propitiation and worship, of the god.

The importance of the power place is determined by the spiritual achievement of that first sage, for his success will draw other yogis to the place.

Success will be seen in terms of the attainment of buddhahood or by spiritual powers demonstrated as magic or miracles.

Perhaps the first great name associated with the place will initiate a lineage of disciples through successive generations who will further sanctify it.

Or if a single lineage does not gain a monopoly of the site then it will become associated with various lineages. Whether of one or multiple lineages the site becomes hallowed by tradition.

In Buddhist tradition, the most powerful sanctifying activity of a human being is Shakyamuni's enlightenment.

Shakyamuni's attainment under the bodhi tree in Bodhgaya has marked that place as the centre of the Buddhist world.

Located in the middle of the Ganges plains, with no apparent significant geomantic features, Shakyamuni's seat under the bodhi tree, called Dorjeden, the Indestructible Throne, is consecrated as a power place primarily through human activity.

Guru Rimpoche's place of enlightenment at Yanglesho (Pharping) in the Kathmandu Valley is a south-facing rock-cave on a ridge.

In Tibet, the moment of a yogi's enlightenment is not usually recorded as such and it is simply the places of meditation of the innumerable buddha-lamas that are recalled.

Until a power place has been empowered by a buddha-lama, although it may possess auspicious geomantic features, it is still part of the profane landscape, perhaps a place unremarked and unused.

If it is a cave, perhaps goat or yak herders have sheltered in it, their animals leaving centuries of accumulated dung along with the charcoal of ancient fires on the floor.

It may have been shunned due to the recognition of a noxious spirit in residence, but this in itself may not be sufficient to keep herders away. Whether or not it is functional, it is basically a hole in the ground or the rock.

The place is sanctified by a lama or tantric magician. His presence there is alone sufficient to empower it.

But if he stayed there for a significant length of time,

then certainly he will be the subject of legend and this legend adds support to the basic fact of his buddha-awareness impregnating the rock and changing the perceived pattern of energy from a chaotic superficial malignity -

or potential malignity - to a locus of transcendental awareness at the centre of the mandala.

A cave is opened by the yogi whose meditation sanctifies it. A mountain power place is opened by the first adept to circumambulate it.

A hidden valley is opened by a treasure-finder who reveals Guru Rimpoche's map and leads his followers into it.

The followers of a particular religious order may consider a power place 'open' only if the founder of that order or one of its masters opened it.

The conjunction of auspicious geomantic features and the sometime presence of a yogi who has empowered the place produces an ambience immediately accessible to the pilgrim who approaches that power place with devotion.

The feelings that are evoked may be described in terms of power, but through Buddhist devotional and meditational praxis the yogi transforms the latent energy of the place into transcendental awareness and its compassionate responsiveness.

This state of buddha-mind is conducive to the discovery of hidden treasure.

Power places are by definition places of hidden treasure; but according to the doctrine of the Nyingma order only those places empowered by Guru Rimpoche or his primary emanations contain caches of accessible treasure.

When Guru Rimpoche was travelling throughout Tibet, meditating in the innumerable cave and temple power places, he concealed treasures in each for the fortunate beings of future generations, and these places are called treasure power places (terne).

Tsari: The Crystal Mountain Of Supreme Bliss

The Immaculate Crystal Mountain of Tsari provides the definitive Tibetan pilgrimage.

It is the palace of the buddha-deity Demchok, Supreme Bliss, and his mandala of deities.

And it is also a principal abode of the sky dancers, amongst whom Khandroma Dorje Phakmo is supreme.

More than Kang Rimpoche and Labchi, it is the tantric power place par excellence, a testing place for yogis where the sky dancers dwell.