Shambhala: The Outer Tradition by Suzanne Duarte

Over the centuries, there have been many who have sought the ultimate good and have tried to share it with their fellow human beings. To realize it requires immaculate discipline and unflinching conviction. Those who have been fearless in their search and fearless in their proclamation belong to the lineage of master warriors, whatever their religion, philosophy, or creed. What distinguishes such leaders of humanity and guardians of human wisdom is their fearless expression of gentleness and genuineness – on behalf of all sentient beings. We should venerate their example and acknowledge the path that they have laid for us. They are the fathers and mothers of Shambhala, who make it possible, in the midst of this degraded age, to contemplate enlightened society. ~

Chögyam Trungpa, from “The Shambhala Lineage,” the final chapter in Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior

Introduction

This is a revision of the first of three talks I gave in March 1995 at the Shambhala Center in São Paulo, Brasil. It reflects my personal understanding of the history and tradition of Shambhala, after having studied and taught the Shambhala teachings as presented by Chögyam Trungpa, and having done a bit of research.

When Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche first began to present the Shambhala teachings in 1976, I felt like the deepest longings of my heart were being answered. As I studied these teachings over the years, I recognized that the vision of Shambhala has a universal mythic dimension that resonates deeply in the human heart. The material I am presenting as “outer Shambhala” is intended to demonstrate the historical depth and vastness of the Shambhala tradition. It is a weighty tradition, rich in meaning and in the gifts that it offers humanity. It is not an eclectic new-age fantasy, but an ancient tradition that is still alive in Asia, North America and Europe today.

What is and was Shambhala?

Shambhala is the vision of a contemplative society in which the possibility of cessation is realized collectively because people meditate and thereby cease to generate samsara, or confused existence. Shambhala is an ideal that has been glimpsed, however briefly, in different places and cultures, and seems to exist in the collective unconscious as an archetype. As an archetype, it is a universal dream and longing for compassion and wisdom to manifest on the collective level, in ways of life that enable the highest human values to be shared and lived in common. This dream or ideal shows up all over the world as the aspiration to organize our world so that all people may prosper by living wholesome, dignified lives in peace and harmony - without the pettiness of greed and selfishness, and without the delusions and deceptiveness that follow greed and selfishness, which give rise to samsara, domination, war and oppression. The vision of Shambhala is that this is possible, that it has happened before and it can happen again.

Shambhala is said to have been a kingdom in Central Asia that flourished somewhere along the old Silk Road . It was said to be a place of high culture and learning where the ideas, material commerce, and spiritual practices of many traditions and cultures intermixed in an inquisitive and appreciative atmosphere of peace and prosperity. Their way of life joined Heaven (vision) and Earth (practicality) in harmony. There was wealth as well as a high level of spiritual realization among the inhabitants. It was a sanctuary for the highest human values and traditions, free from strife and jealousy because the people had what they needed, including their own dignity. Their rulers were enlightened kings who were just, powerful, and merciful. The sacred arts and scriptures of many religions were placed in the libraries for safekeeping for the future. Shambhala regarded itself and is still regarded as the repository for the spiritual wisdom and power that would be needed to save the world from the darkness and depravity that would threaten to destroy all civilization in the future.

As is common in Central Asia, and elsewhere in the world, the distinctions between myth, history and material reality have been blurred by time as the legends have come down through oral tradition. Shambhala seems to have existed physically in historical time but its legend has taken on a mythic and symbolic dimension as it has been embellished and deepened through spiritual contemplation and storytelling.

The first king of Shambhala , Suchandra (Tib. Dawa Sangpo), is said to have journeyed to India to receive the highest teachings of the Buddha just before he died (5th century BCE). This was the Kalachakra Tantra , the teachings on the Wheel of Time. Suchandra wrote it down and taught it to the people of Shambhala. He was followed by a line of six more kings who all taught and practiced the Kalachakra, and then by a second line of kings called the Rigdens, of whom there will be 25 by the time the final King appears. Here we get into myth and prophesy. At a certain point, when all the inhabitants of Shambhala became enlightened, the kingdom disappeared from ordinary material existence into another realm. The Rigden Kings are said to still be watching over human affairs and instructing certain humans through dreams and visions.

The prophesy is that the world will degenerate into a dark age of chaos as materialism becomes dominant and spiritual values and practices disintegrate. Here’s one description of the dark age from Edwin Bernbaum’s The Way to Shambhala (1980, p. 82):

Wealth and piety will decrease day by day, until the world will be wholly depraved. Then property alone will confer rank; wealth will be the only source of devotion; passion will be the sole bond of union between the sexes; falsehood will be the only means of success in litigation; and women will be objects merely of sensual gratification. Earth will be venerated but for its mineral treasures. . . .

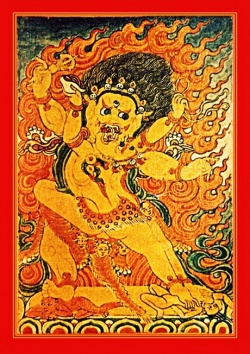

When the Lords of Materialism have all but consolidated their stranglehold on life, the 25th Rigden King will emerge and lead the warriors of Shambhala in the final great battle. After they have vanquished the forces of darkness, the 25th Rigden will usher in a new golden age of peace. The warriors of Shambhala will have been waiting in the wings, so to speak, for many lifetimes, waiting to be reborn at the time when they can fight in the Great Battle for Shambhala. This is a prominent part of the myth that is still fervently believed by people in Central Asia. Shambhala warriors maintain their practices lifetime after lifetime, aspiring to become purified enough to be reborn in Shambhala so that they may engage in the final Great Battle that will make life on Earth worthwhile again.

The Shambhala myth in its simplest form is that the fortunate seeker makes a perilous journey to a hidden sanctuary that holds a source of liberation and renewal that will eventually transform not only the seeker, but the outside world as well. This myth has been interpreted on the material level as well as on the purely symbolic and spiritual level. On the symbolic level, the vision or archetype of Shambhala exists in all of our hearts, and the aspiration to go to Shambhala is universal. In Tibet, the secret meaning of Shambhala is “the source of happiness,” which Trungpa Rinpoche called “sacred outlook.”

The Shambhala tradition is very old, and also completely up-to-date and relevant to our situation in the world today. The stories vary from each other in many details, such as when it all began, where Shambhala was or is, and how to get there. But the legend of Shambhala is alive in Central Asia even to this day. It can be found in Kashmir and eastern Russia, Siberia, Ladakh, Mongolia, China, and of course Tibet.

Important evidence of the historical existence of Shambhala is provided by the many wall frescos and thangkas in and from Central Asia that depict the Kingdom of Shambhala, as well as ancient texts that describe Shambhala in different languages, and guidebooks on how to get there. Many of these have been discovered by Westerners within the last century in arid places along the Northern and Southern Silk Roads that connected the Middle and Far East. In the caves of Dunhuang in China, thousands of beautiful frescos, sculptures, and ancient manuscripts were found, showing an advanced civilization influenced by a rich mixture of traditions and cultures. The Kalachakra Tantra itself shows the influences of Nestorian Christianity, Manichaeism, and Islam. Manichaeism has influences of Gnosticism and Zoroastrianism from Persia and the ancient Middle East. The art also shows these influences.

Mogao Cliff, Dunhuang

The International Dunhuang Project , “The Silk Road Online,” is an exciting international collaboration to make information and images of all manuscripts, paintings, textiles and artifacts from Dunhuang and archaeological sites of the Eastern Silk Road freely available on the internet and to encourage their use through educational and research programs.

Interestingly for students of the Karma Kagyu and Rimé traditions of Tibetan Buddhism, the Kalachakra Tantra, and presumably the legend of Shambhala, came to Tibet from India through Naropa, the abbot of Nalanda University and one of the forefathers of the Kagyu lineage. The Kalachakra teachings had been sequestered in the Kingdom of Shambhala for hundreds of years, until an Indian yogi-scholar set out for Shambhala in order to receive those teachings. On this journey he encountered a Shambhala king who manifested as Manjushri and granted him the Kalachakra initiation. This scholar returned to India in 966CE, where he defeated Naropa in a debate, and then initiated him into the Kalachakra. In the next century two Kashmiri students of Naropa brought the Kalachakra to Tibet and established two lineages of those teachings. Subsequently, the Kalachakra tradition vanished from India after the Muslim invasions, which is the reason that Tibet became the source of the Kalachakra and Shambhala traditions. At least that is the story in the Wikipedia account of the History and Origins of the Kalachakra Tantra and its spread to Tibet.

Location of Shambhala

According to legends and guidebooks, Shambhala existed north of Tibet within a double ring of snow-capped mountains. Edwin Bernbaum, in The Way to Shambhala: A Search for the Mythical Kingdom beyond the Himalayas , says that there are many opinions on its exact location. Many have searched for it, but no one has found any verifiable evidence of it. Some still hope to find it somewhere between the Kunlun Mountains and Dzungaria , between the Pamirs and Dunhuang. Bernbaum speculates that it may have occupied the Tarim Basin or the Turpan Depression , or all of Central Asia between Dunhuang and the Pamirs.

The following is the best online map I’ve found of the area in question, showing the northern and southern Silk Routes and the topography. Note Dunhuang in the far right of the map:

There is evidence that the climate in this region was once very hospitable for crops and people, therefore able to accommodate an extensive advanced civilization, but that it changed, perhaps suddenly, becoming extremely arid and practically uninhabitable.

However, as recently as the late 1920’s the Shambhala legend was still very much alive in Mongolia. Henning Haslund’s Men and Gods in Mongolia tells the story of H.H. Seng Chen Gegen, the leader of the Torgut tribe of Mongols. Gegen built Oreget, a beautiful white city laid out in a mandala pattern in the Tien Shan mountains – the “celestial mountains.” The city and the leader himself were very Shambhalian. He was a reincarnated lama trained in Tibet, as well as a skilled secular leader who worked to preserve the freedom of the Mongols. He said that the Mongolian nomad warrior represents the “primordial spark”: “In the genuine nomad burns the flame of the primordial which all peoples have possessed and which alone confers true human happiness.”

This is Seng Chen Gegen’s prophesy:

Beyond the most distant borders of our neighbors (Russia and China) live other peoples who also languish in the pursuit of vain earthly profit, but they will perceive the need of deliverance long before our neighbors. They will return to seek the primordial spark; they will seek it in nature and they will find it among our flocks.

From us shall come the salvation of mankind. The primordial spark shall be derived from us, but its light shall be spread from the West.

Seng Chen Gegen’s prophesy is the Mongolian version of the Shambhala prophesy. His mission among his people was not for their benefit alone, but for the world as a whole, as befits a true Shambhalian.

Hidden Valleys

The Hunza Valley

There are many stories and legends of hidden valleys where people live long, happy lives secluded from the rest of the world – or, more specifically, from Western civilization. In the early 1970’s I was fascinated with stories of the Hunzas. The beautiful, hidden Hunza Valley, surrounded by high, snow-capped mountains in northern Pakistan, is said to have inspired novelist James Hilton as the archetype of Shangri-la (another name for Shambhala) in his 1933 novel Lost Horizon. Both the novel and the film by the same name (directed by Frank Capra and starring Ronald Coleman) popularized the Shambhala archetype in the West.

The Hunzas lived in harmony with nature, were highly literate, extraordinarily healthy, wholesome, friendly, and hospitable. They had an average lifespan of 100 years. Unfortunately, after the Karakoram Highway linking Pakistan with China brought tourism to Hunza in the late 20th century, the average lifespan there steadily declined. The Muslim Hunza story, much like that of Buddhist Ladakh, is a cautionary tale of what happens to stable, sustainable, subsistence cultures in fragile mountainous ecosystems when exposed to modernity through tourism and political intervention. Both the cultures and the environment become degraded by consumerism and militarization, which seem to go hand-in-hand.

Another variation on the hidden-valley motif is an old Chinese legend written in a poem called A Song of Peach Blossom River, composed in the 8th century but taken from a story written in the early 5th century. It tells of a fisherman drifting on a river in China enjoying the spring peach blossoms.

He just drifts along appreciating the beauty of the blossoms along the river, the lovely fragrance in the air, the gentle breeze. Suddenly he finds himself at the end of a blue stream where there is a cave. Its mouth is so small that he has to crawl to pass through it. But he emerges onto a wide path that leads into a beautiful valley filled with forests, meadows, gardens and beautiful houses. Everything is arranged pleasingly, very clean and orderly, and an atmosphere of peace and harmony pervades the valley and hills surrounding it.

He meets the people who live there and they welcome him into their homes. They are dignified yet warm, spiritually advanced and cultured, elegant yet simple. The people and their clothing and all the things he sees seem very vivid and clear. They have been apart from the world for a long time and are living in harmony with heaven and earth. They have plenty to eat and share everything freely with him. He stays for a while but becomes homesick, thinking of his family and worldly ties. So he leaves, intending to bring back his family. He tries to remember each landmark on the way so that he can return. But when he looks for it again, the clouds and mists change the appearance of the cliffs and peaks and forests, and he never finds his way back again.

Some stories of hidden valleys, like Hunza and the Peach Blossom River, seem to echo the legend of Shambhala. The moral of Peach Blossom is that if you should stumble upon an enlightened society such as Shambhala, you are fortunate if you realize how special, how precious, it is. If you leave, intending to bring all your family and social conditioning back to it, you may not be able to find it again.

In most of the legends of Shambhala, people do not stumble upon it, but make arduous journeys requiring the seeker to face great hardships and challenges that test his character and his spiritual attainment. In the process of making the journey, one’s energy and motivation must be purified. In other words, family conditioning must be transformed.

Some people of advanced spiritual attainment have dreams and visions of going to Shambhala where they receive teachings that they must bring back to the world. They want to stay, but they are instructed to go back to the world with the message of Shambhala, and they are promised that they will be reborn in Shambhala when the time is right. This was the case with Chögyam Trungpa, who brought the Shambhala tradition from Tibet to the West. In his popular book Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior, Trungpa presented the inner or spiritual meaning of Shambhala so that Westerners could be inspired by the vision of Shambhala, practice it, and work together to make it a reality.