Maha Vagga

Mahavagga -- The Great Chapter

Pabbaja Sutta (Sn III.1) -- The Going Forth. King Bimbisara, struck by the young Buddha's radiant demeanor, follows him to the mountains to discover who he is and whence he comes.

Padhana Sutta (Sn III.2) -- Exertion/The Great Struggle [two translations: Thanissaro Bhikkhu, tr. | John D. Ireland, tr.]. The ten armies of Mara approach the Bodhisatta (Buddha-to-be) in an unsuccessful attempt to lure him from his meditation seat.

Subhasita Sutta (Sn III.3) -- Well-spoken. Four characteristics of speech that is well-spoken.

Salla Sutta (Sn III.8) -- The Arrow [John D. Ireland, tr.]. Death and loss surround us, yet the wise know that the path to lasting happiness calls for abandoning our sorrow, grief, and despair.

Nalaka Sutta (Sn III.11) -- To Nalaka. A sutta in two parts. The first part gives an account of events soon after the birth of the Bodhisatta (Buddha-to-be). The second part describes the way of the sage.

Dvayatanupassana Sutta (Sn III.12) -- The Noble One's Happiness (excerpt) [John D. Ireland, tr.]. The Buddha observes that what most people call happiness, the wise call suffering; what the wise call happiness, others call suffering. No wonder the Dhamma is so difficult to comprehend!

The last Vagga of Saµyutta Nikæya is made up of twelve saµyuttas, the list of which gives a clear indication of the subjects dealt with in this division:

Magga Saµyutta,

Bojjha³ga Saµyutta,

Satipa¥¥hæna Saµyutta,

Indriya Saµyutta,

Sammappadhæna Saµyutta,

Bala Saµyutta,

Iddhipæda Saµyutta,

Anuruddha Saµyutta,

Jhæna Saµyutta,

Ænæpæna Saµyutta,

Sotæpatti Saµyutta and

Sacca Saµyutta.

The main doctrines which form the fundamental basis of the Buddha’s Teaching are reviewed in these saµyuttas, covering both the theoretical and practical aspects. In the concluding suttas of the vagga, the ultimate goal of the holy life, Arahatta Phala, Nibbæna, end of all suffering, is constantly kept in full view together with a detailed description of the way of achieving it, namely, the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Path of Eight Constituents.

In the opening suttas it is pointed out how friendship with the good and association with the virtuous is of immense help for the attainment of the Path and Perfection. It is one of the supporting factors conducive to the welfare of a bhikkhu. Not having a virtuous friend and good adviser is a great handicap for him in his endeavours to attain the Path.

In the Ku¼ðaliya Sutta, the wandering ascetic Ku¼ðaliya asks the Buddha what his objective is in practising the holy life. When the Buddha replies that he lives the holy life to enjoy the Fruits of the Path and the bliss of liberation by knowledge, the ascetic wants to know how to achieve these results. The Buddha advises him to cultivate and frequently practice restraint of the five senses. This will establish the threefold good conduct in deed, word and thought. When the threefold good conduct is cultivated and frequently practised, the Four Foundations of Mindfulness will be established. When the Four Foundations of Mindfulness are well established the Seven Factors of Enlightenment will be developed. When the Seven Factors of Enlightenment are developed and frequently applied, the Fruits of the Path and liberation by knowledge will be achieved.

In the Udæyi Sutta, there is an account of Udæyi who gives confirmation of such achievements through personal experience. He tells how he comes to know about the five khandhas from the discourses, how he practices contemplation on the arising and ceasing of these khandhas, thereby developing Udayabbaya Ñæ¼a which, through frequent cultivation, matures into Magga Insight. Progressing still further by developing and applying frequently the Seven Factors of Enlightenment he ultimately attains Arahatship. In many suttas are recorded the personal experiences of bhikkhus and lay disciples who on being afflicted with serious illness are advised to cultivate and practice the Seven Factors of Enlightenment. They recount how they are relieved, not only of pains of sickness but also of suffering that arises from craving.

In Saku¼agghi Sutta, the bhikkhus are exhorted by the Buddha to keep within the confines of their own ground, i.e., the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, namely, contemplation of body, sensation, mind and mind-objects. They can roam freely in the safe resort guarded by these outposts of Four Foundations of Mindfulness, unharmed by lust, hate and ignorance. Once they stray outside their own ground, they expose themselves to the allurements of the sensuous world. The parable of falcon and skylark illustrates this point. A fierce falcon suddenly seizes hold of a tiny skylark which is feeding in an open field. Clutched in the claws of its captor, the unfortunate young bird bemoans its foolishness in venturing outside of its own ground to fall a victim to the raiding falcon.

"If only I had stayed put on my own ground inherited from my parents, I could easily have beaten off this attack by the falcon." Bemused by this challenging soliloquy, the falcon asks the skylark where that ground would be that it has inherited from its parents. The skylark replies, "The interspaces between clods of earth in the ploughed fields are my ground inherited from my parents." "All right, tiny tot, I shall release you now. See if you can escape my clutches even on your own ground."

Then standing on a spot where three big clods of earth meet, the skylark derisively invites the falcon, "Come and get me, you big brute." Burning with fury, the falcon sweeps down with fierce speed to grab the mocking little bird in its claws. The skylark quickly disappears into the interspaces of the earth clods, but the big falcon, unable to arrest its own speed, smashes into the hard protruding clods to meet its painful death.

In Bhikkhunupassaya Sutta, the Buddha explains for Ænanda’s benefit two methods of meditation. When established in the Four Foundations of Mindfulness, a bhikkhu will experience a beneficial result, gradually increasing. But should his mind be distracted by external things during the contemplation on body, sensation, mind or mind-object, the bhikkhu should direct his mind to some confidence-inspiring object, such as recollection of the virtues of the Buddha. By doing so, he experiences joy, rapture, tranquillity and happiness, which is conducive to concentration. He can then revert back to the original object of meditation. When his mind is not distracted by external things, no need arises for him to direct his mind to any confidence-inspiring object. The Buddha concludes his exhortation thus: "Here are trees and secluded places, Ænanda. Practice meditation, Ænanda. Be not neglectful lest you regret it afterwards."

As set out in the Cira¥¥hiti Sutta, the Venerable Ænanda takes this injunction to heart and regards the practice of the Four Methods of Steadfast Mindfulness as of supreme importance. When a bhikkhu by the name of Badda asks the Venerable Ænanda, after the death of the Buddha, what will bring about the disappearance of the Buddha’s Teaching, the Venerable Ænanda replies, "So long as the practice of the Four Methods of Steadfast Mindfulness is not neglected, so long will the Teaching prosper; but when the practice of the Four Methods of Steadfast Mindfulness declines, the Teaching will gradually disappear."

Ænæpænassati meditation, one of the methods of body contemplation, consists in watching closely one’s in-breath and out-breath and is rated highly as being very beneficial. In the Mahæ Kappina Sutta, the bhikkhus inform the Buddha, "We notice, Venerable Sir, that bhikkhu Mahæ Kappina is always calm and collected, never excited, whether he is in company or alone in the forest!" "It is so, bhikkhus. One who practises Ænæpænassati meditation with mindfulness and full comprehension remains calm in body and collected in mind, unruffled, unexcited."

The Icchæna³gala Sutta describes how the Buddha himself once stayed for the rains-residence of three months in Icchæna³gala forest grove in solitude practising Ænæpænassati meditation most of the time. Ænæpænassati meditation is known as the abode of the Enlightened Ones, the abode of the Noble Ones.

When fully accomplished in the cultivation of the Seven Factors of Enlightenment, through practice of body contemplation or Ænæpænassati meditation, one becomes firmly established in unshakable confidence in the Buddha, the Dhamma and the Saµgha. The moral conduct of such a person, through observance of precepts, is also without blemish. He has reached, in his spiritual development, the stage of the Stream-winner, Sotæpatti Magga, by virtue of which, he will never be reborn in states of woe and misery. His path only leads upwards, towards the three higher stages of accomplishment. He has only to plod on steadfastly without looking backwards.

This is explained in the Pa¥hama Mahænæma Sutta, by the simile of an earthern pot filled partly with gravel and stones and partly with fat and butter. By throwing this pot into water and smashing it with a stick, it will be seen that gravel and stones quickly sink to the bottom while fat and butter rise to the surface of the water. Likewise when a person who has established himself in the five wholesome dhammas of faith, conduct, learning, charity and insight dies, his body remains to get decomposed but his extremely purified mental continuum continues in higher states of existence as birth-linking consciousness, patisandhi citta.

In the concluding suttas are expositions on the Middle Path, the Four Noble Truths and the Noble Path of Eight Constituents.

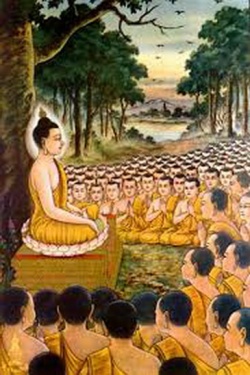

The Buddha’s first sermon, the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta, appears in the last saµyutta, namely, Saccasaµyutta.

The Buddha did not make his claim to supremely perfect enlightenment until he had acquired full understanding of the Four Noble Truths. "As long, O bhikkhus, as my knowledge of reality and insight regarding the Four Noble Truths in three aspects and twelve ways was not fully clear to me, so long did I not admit to the world with its devas, mæras and brahmæs, to the mass of beings with its recluses, brahmins, kings and people that I had understood, attained and realized rightly by myself the incomparable, the most excellent perfect enlightenment."

The Buddha concluded his first sermon with the words "This is my last existence. Now there is no more rebirth for me."