The Monasteries of Tibet: Tragedy and Heroism

During the past half-century, the monasteries of Tibet have been places of deep tragedy and high heroism. Monasteries have been destroyed, their religious artifacts removed, and whole libraries burned. Monks and nuns have been subjected to unbelievably cruel humiliation and torture. (cf: Palden Gyatso “The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk” 1997; Ani Pachen, “Sorrow Mountain: The Journey of a Tibetan Warrior Nun, 2000; Ama Adhe: “The Voice that Remembers: A Tibetan Woman’s Inspiring Story of Survival” 1997 White Paper on Human Rights, The Government of Tibet in Exile http://www.tibet.com)

Many Tibetans who tried to maintain their faith and dignity have died. Others have escaped Chinese oppression by crossing the Himalayas on foot to become refugees. Some who remained have struggled against great odds and scant resources to start rebuilding the devastated monasteries.

Starting in 1956 in Kham and Amdo and in 1959 in Central Tibet, monasteries were systematically looted of articles of value, books were burned, and the buildings dismantled and destroyed. Teams came to extract precious stones, and metallurgists arranged for the removal of metal objects. The walls were dynamited and wooden pillars and beams removed. Clay images were destroyed in the hope of finding valuable objects inside. Hundreds of tons of statues, thangkas, and other treasures were shipped to China to be melted down or sold on the international antique market.

The destruction of the monasteries was accompanied by an intense repression of religion and humiliation of monks and nuns. Religious texts were burned, mixed with manure, and used for wallpaper. Mani stones were used for making toilets and pavement. Monks and nuns were forced to have sex in public. Ruined monasteries were turned into stables and pigsties.

When jailed monks and nuns were often tortured to extract confessions, to renounce Buddhism, and to embrace Communism. Methods of torture included setting guard dogs on prisoners, use of electric batons especially on women prisoners in perverted and degrading manners, inflicting cigarette burns, and administration of electric shock. Monks and nuns were beaten with electric batons, rifle-butts, and iron bars.

Ngawang Kusho recalled, “Even beyond the beatings, starvation, cold, and forced labor, the most difficult thing for me to understand were the public humiliations that people were forced to endure. There were times when female PLA soldiers would try to force me to drink urine. When I refused it was spilled over my face. We lamas were made to clean fecal matter, which was to be used as fertilizer, out of makeshift toilets. The toilets consisted of a deep hole dug in the ground, which was covered with two planks. Quite often, when we climbed down into the holes to clean them out, female PLA soldiers amused the prison staff by purposely urinating from the top so that the urine fell on our faces.” Ngawang Kusho was sentenced to eighteen years of imprisonment but was ultimately detained for twenty (Ama Adhe 1997: 183).

By 1976 only some eight monasteries remained, most apparently having been destroyed between 1955 and 1961. Among those that were destroyed were Samye, Ganden, Sakya, Tsurphu, Mindroling, and Menri. Of the 600,000 monks and nuns, 110,000 were tortured and murdered.

With almost heroic courage and commitment to their Buddhist heritage, Tibetans are rebuilding their monasteries and recommencing their traditions of pilgrimage. Almost all of the rebuilt or renovated monasteries were the result of the personal initiatives of Tibetans who contributed their meager finances and labor. Aid for reconstruction provided by the Chinese Government was a very small fraction of the total expenses of reconstruction. Reconstruction and renovation of monasteries can be done only after receiving permission from the Chinese Bureau of Religious Affairs. Such permission is granted only after a long period of bureaucratic red tape during which Tibetans have to make repeated appeals and are required to listen to lectures on the negative influences of religion.

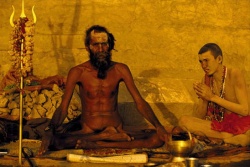

The Chinese sponsored reconstruction of monasteries appears to serve only their political and economic purposes. The state-sponsored monasteries often serve primarily as museums for tourists rather than serve as genuine cultural and religious institutions. The monks permitted by the government to live in the state-supported monasteries serve primarily as exhibits, showpieces, and caretakers instead of genuine religious students and practitioners. (“During the first half of 1979, Tibetans were forced to take part in the rapid renovation of the monasteries that were visible from the highways, while monasteries in more isolated regions were ignored. Sometimes a small chapel would be constructed on the former site of a large monastery. To replace the gold and silver statues that had been looted, new ones were sculpted of clay. The walls were painted in the traditional manner, and paintings of the Tibetan deities were hung on the walls. But there were no rinpoches left to consecrate the chapels, and there was no one left alive who remembered the scriptures. The site of these lifeless restorations brought tears to the eyes of the Tibetan people”, Ama Adhe 200: 189-190)

Today, China refuses to permit the colleges of the monastic universities to educate in the traditional manner. Admission to monasteries is based upon the goal of fostering “a large number of fervent patriots in every religions who…firmly support the Socialist path, and safeguard national and ethnic unity.” The Chinese government tightly controls the numbers of monks at each monastery and hence limits the vigor and effectives of education that is available through the monastic universities. Before the Chinese invasion, Sera had nearly 8000 monks; now it is allowed 300. Drepung once had 10,000, now has 400 monks; Ganden’s population has been reduced from 5,600 to 150.

The Chinese government is apparently alarmed by the burst of reconstruction of monasteries that followed a brief period of liberalization. The monasteries are viewed as bastions of Tibetan nationalism, and “Democratic Management Committees” have been established to supervise the newly created monasteries and nunneries. “Work Inspection Teams” supervise the education of monks and nuns.

The 1994 Third Forum on Work in Tibet recommended to “put an end to the unbridled construction of monasteries/nunneries as well to the unbridled recruitment of monks/nuns. The disciplinary coed issued on July 20, 1997 forbids spiritual teaching outside monastic institutions. Identify cards are issued to “government-approved” monks and nuns. “Patriotic Education Work Units” force monks and nuns to denounce the Dalai Lama and to pledge allegiance to the Communist Party. Non-compliance may cause expulsion from monasteries and nunneries. In the four years, 1996-1999 the Dharmsala-based Tibetan Center for Human Rights and Democracy documented 541 arrests of monks and nuns and 11,000 expulsions from monasteries and nunneries.

In March 1998, the Deputy Party Secretary of the TAR, Raidi reported that “35,000 monks and nuns in more than 700 religious institutions have been rectified by patriotic education.”

Destruction of monasteries is continuing. “Unpatriotic” monasteries have been closed down and some have been demolished. In 1995 Samdrupling, Sungrabling, Drigung Shert, and Shigatse’s Jonang Kumbum monasteries were closed down. Claiming that they had been constructed without permission, the authorities dismantled the Shongchen nunnery in Shigatse, Drag Yerpa hermitage and the Rakhor nunnery.