The Third Jewel: The Sangha by Arnie Kozak, Ph.D

The Buddha's first followers were his five former ascetic colleagues. Soon, he went from teaching men who were already renunciants to lay people. A wealthy young man named Yashas became a follower and attained enlightenment under the Buddha's tutelage. Yashas' father also became a follower but as a lay practitioner (upsaka). Lay followers did not follow monastic rules, but practiced the teaching by taking the Triple Refuge: buddha, dharma, sangha. Yashas' mother also took refuge in the Triple Jewel and became the first female lay follower. In the days before Facebook, Buddha's teaching caught on. Through the social networking means available in the sixth century B.C.E., friends of Yashas came, and friends of friends. Word spread. The Buddha sent the first sixty enlightened ones out to spread the teachings. Noted Buddhist scholar Kevin Trainor cites the Buddha saying, “Travel forth, monks, for the benefit of the many, for the happiness of the many, out of compassion for the world, for the well-being, benefit, and happiness of gods and humans.”Despite the Buddha's repudiation of the caste system, not everyone was welcome in the sangha. If you were a debtor, a criminal, runaway slave, or other person shunned by society, you were not welcome. The Buddha likely made such rules mindful of not offending his wealthy patrons upon whose generosity the sangha depended. In this way, he was a skilled politician and not detached from the practical realities of life. The sangha depended upon the patronage of kings and the wealthy. To this end accommodations were made. The most controversial issue where the Buddha did depart from social norms was allowing women to be ordained as nuns (bikkhunis). It took some repeated pleading, however, from his Aunt Prajapati.

The Buddha's main hangout was in the Jeta Grove where he and the sangha spent nineteen rainy seasons (outside of the ancient city of Shravasti). The Jeta Grove was donated by Anathapindaka, who bought the spread from Prince Jeta. Jeta drove a hard bargain and Anathapindaka had to cover the ground with coins to secure it for the sangha. With all that coin, Jeta built quite a country retreat for the monks. This compound, with its combination of land and rich benefactors, served as a model for Buddhism spreading throughout Asia. The monasteries that emerged from these auspicious beginnings also served as cultural institutions. A central component of the monastery was the dharma hall and the library.

The Buddha and the sangha wandered around much of what is today Northern India. During the three-month monsoons, they would take refuge in special places built by wealthy patrons, like the Jeta Grove. They also did not want to travel during the rainy season for fear of injuring life that may be out during the rains, such as worms.

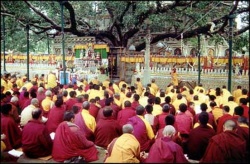

Monastery (vihara) life consisted of meditation, initiation rituals, study, and recitation of what later became the Pali Canon. Two traditions emerged:the forest refuge where monks could do intensive meditation practice, and the village monastery where they served the local community through education, rituals, and also did their own practice. In some places, monks retreated to caves. Charismatic leaders led many of these communities. Contract with the Community

Lay practitioners were known as upasaka (males) and upasikas (females). A lay practitioner becomes so by formally reciting the Triple Refuge and committing to the five precepts in a ceremony with other members of the community. In traditional Buddhist societies (for example, Sri Lanka), there is little emphasis on meditation and more emphasis on generosity (dana) and morality (sila).

The most basic act of dana is a food offering to wandering monks. Or, as in Sri Lanka, women will take prepared food to the monastery for the monks. In Tibet, generosity may take the form of the “tea offering,” where money is donated so that all the monks can have yak butter tea. The laity can also “sponsor” the recitation of mantras or sutras. Money, clothing, flowers, and incense may also be given.

Generosity is an important part of spiritual practice. To give is to overcome ego-based attachment to things. It also helps to foster a sense of interconnectedness. According to the Jataka tales, that recount the “past lives” of the Buddha, the Buddha made a generous offering of himself to a hungry tigress so that she could sustain the strength to feed her young. Such selfless acts also generate merit (punya) for the lay practitioner, and the generation of merit is a primary motivation in Asian cultures.

On special occasions the lay community will adopt additional precepts such as not eating anything other than lemon water after lunch; no dancing, singing, music, ornamenting the body with perfumes, garlands, etc.; or not sleeping in high and luxurious beds (monks already partake of these restrictions). In Asia, the focus for the laity is on right conduct/action rather than on the meditative disciplines, and also visiting holy pilgrimage sites. In Tibet, prostrations and turning prayer wheels are central practices for the lay practitioner. Strength in Numbers

The monastic setting certainly provides a place for individuals willing to devote their entire life to their spiritual development and to the service of all. However, it is not realistic for everyone. Still, there is power in numbers. What you find difficult alone, you might find easier with the strength of numbers behind you. The world around you may not be on the same spiritual page as you are, and this may be an obstacle. You may feel overwhelmed by others who are leading an unreflected life and are caught up in the suffering of greed, hatred, and delusion. Having a group that supports your commitment, that encourages you to proceed against what at times can seem to be overwhelming odds, can make all the difference between staying on the Path or falling off.As you sit to do your meditation, perhaps you start wondering why you are sitting on a cushion when you could be watching Law and Order. Perhaps work beckons or the house needs cleaning. Without a sangha to keep you on track, over time the voices in your head that discourage you from your practice may get louder and louder until they crowd out that little voice inside yourself that urges you onward. The sangha can help bring you back to the path and hold you there. The sangha can be a powerful force of encouragement.