The Three Bodies of the Buddha

Trikaya is a Sanskrit word used in the Buddhist context to refer to levels of manifestation or activity. Tri means three and trikaya as a concept concerns three levels of buddhahood.

Three bodies of the Buddha (Skt. trikaya)

1. Dharmakaya: The Dharma-body, or the "body of reality", which is formless, unchanging, transcendental, and inconceivable. Synonymous with suchness, or emptiness.

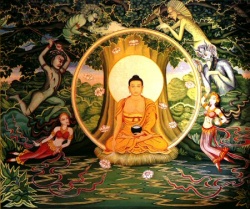

2. Sambhogakaya: the "body of enjoyment", the celestial body of the Buddha. Personification of eternal perfection in its ultimate sense. It "resides" in the Pure Land and never manifests itself in the mundane world, but only in the celestial spheres, accompanied by enlightened Bodhisattvas.

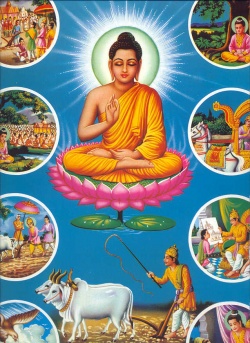

3. Nirmanakaya: the "incarnated body" of the Buddha. In order to benefit certain sentient beings, a Buddha incarnates himself into an appropriate visible body, such as that of Sakyamuni Buddha.

The incarnated body of the Buddha should not be confused with a magically produced Buddha. The former is a real, tangible human body which has a definite life span, The latter is an illusory Buddha-form which is produced with miraculous powers and can be withdrawn with miraculous powers.

Shakyamuni, the historical Buddha who is generally considered one of many buddhas to have come to the help of sentient beings, is understood to be accessible in various ways. These are called the dharmakaya, samboghakaya, and nirmanakya. They have been translated into English as: truth-body, bliss- or enjoyment-body, and activity-body.

A simplified explanation is that the dharmakaya is the Absolute. It is the source of everything including buddha activity, and is not different from the Void (Skt. shunyata, Emptiness.) It is not usually experienced except by fully realized beings. It is not normally "prayed to," though it is saluted or praised. Its nature is the subject of discussion.

The sound Aum (Om) evokes the dharmakaya. One explanation found in the Hindu Puranas is that it is the grunt of the Goddess as she gives birth to creation. In Buddhism, that which it represents is entirely unborn.

The 3 components of this syllable, here in a Tibetan form, can also be understood as the kayas, and also as symbolic of the 3 Jewels.

The samboghakaya (enjoyment body) is rarely experienced. Its manifestation is as described in the images used in visualization, and in stories told of deities. It is Manifestation that permits description, and has been referred to as "timeless communication." The sound Ah, the expression of joyous wonder, is written and used to evoke it.

The nirmanakaya is the third "body." It is the phenomenal world; our reality. The sound Hum, which actually means us in Sanskrit (in Tibetan it is rendered as Hung! ) represents it. It is the here-and-now, with all its future potential.

It may be helpful to think of the three as: abstract, mythic and human realms.

In her essay "Some Buddhist Perspectives on the Goddess" in Soaring and Settling (New York: Continuum Press, 1998) Rita M. Gross gives concrete examples with regard to the ritual worship (Skt. sadhana) of the deity, Green Tara.

The late Kalu Rinpoche compared the dharmakaya to the sun the direct perception of which is impossible for us, the samboghakaya is the disc form that we see and of which we say, "It is rising " or "It is setting," and the nirmanakya is the light and heat we experience.

For a detailed explanation.

In the Buddhist tradition which focuses on Buddha Amitabha, his pavilion is bounded by three walls each of which symbolizes one of the kayas: the rim of skulls, of the dorjes, of the lotuses.

The ancient Celts who some scholars believe originated near the Caspian Sea, had a similar belief in the Three Existences: the spiritual, symbolic and physical. Several of their myths, symbolism and practices resemble those of ancient India.

==Is there a 4th kaya==

In "Transforming Poison into Nectar," Drikung Khenchen Konchog Gyaltshen Rinpoche) teaches about empowerment with reference to four kayas.

The 4th kaya is called, Svabhavikakaya (of an essence, or essential.)

- H.E. Tai Situpa, explaining Mahamudra, says," ... svabhavikakaya (Tib. ngo wo nyi kyi ku) is not a further form of manifestation, but denotes the fact that the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya, and nirmanakaya are not separate from each other. They are just three different aspects of the state of a buddha, which is indivisible."

- If we were to compare Dharmakaya to vapor, Sambhogakaya to clouds, and Nirmanakaya to rain, then Svabhavikakaya is the essential nature of them all -- water-ness or moisture.

==A Further Example of Levels of Manifestation and Activity==

Yeshe Tsogyel was once a merchant who lived during the time of a former Buddha when she went before him and swore not to be reborn except for the benefit of beings. She manifested as Ganga, the Indian goddess who sprang from Lord Shiva's topknot to flow as the Ganges, the river watering the plain of north India, and then as Saraswati, the Indian goddess of the flow of language and music. She was once a disciple of Buddha Shakyamuni, as well. Then, according to Nyingma tradition, in 8th century Tibet, Guru Padmasambhava invoked Saraswati to manifest as a woman who would help disseminate the Mantrayana. In the same tradition, Yeshe Tsogyel is an emanation of Samantabhadri, consort of primordial Samantabhadra. Both are Samboghakaya Buddhas. In thangkas, he is depicted as dark blue in colour, and she as pure white. Due to their union, Yeshe Tsogyel was born into this world, first as an Indian princess.

==Aspects of Deity==

Tantric deities, which are the focus of individual practice either through assignment by the guru or through personal connection, are considered to operate in several ways, usually five: body, speech, mind, quality, and action. Sometimes, we speak of a sixth or "essence" aspect. As a "meditational deity" or yidam, Yeshe Tsogyel is regarded as the manifestation of the speech of Vajrayogini, herself a form of Vajravarahi, who is the Sambhogakaya aspect of Samantabhadri. One of her early teachers, Kalasiddhi, is considered the quality of Vajravarahi, and Tashi Chodren, one of her early students was recognized as the activity emanation of Varahi. The word deity is understood in a rather unique way by Buddhists; it is used for lack of a better word. The Tibetan expression is yidam (Skt. ishta.devata) and it refers to a symbolic embodiment that is the focus of mental and ritual practice. Chosen by the teacher or by the student with guidance from the teacher, this figure can act as a psychological complement or support.

Deities are also viewed as mythic figures, but they are understood to arise and return to Emptiness. Although they have no inherent reality nevertheless they do exist, according to such excellent teachers as Khenpo Karthar Rinpoche.

They are not worshipped in the sense of idolatry, though certainly it may seem to be so for example, when someone first encounters people doing full prostrations before images on a shrine. That is one reason for not using the term 'altar,' by the way.

"... religious doctrines have utility rather than truth, ... their importance lies in the effect they have ... ." ~ theologian and Karma Kagyu practitioner, Rita M. Gross

Saraswati: This name is also given to a river, one that no longer exists but once watered northeast India.

==Ancient Egyptian Doctrine of 3==

We cannot know how the ancient Egyptians actually viewed reality, or how they applied their views in their quest for higher meaning, despite all the writing that has been translated. (Think of how it was with many of us before we were so fortunate as to have real teachers, when we only had access to Tibetan Buddhism via vaguely translated books.) They seem to have had a three-part theory of existence that seems similar to the doctrine of trikayas. At least from earliest Old Kingdom times (5,000 Before the Present) beings were considered to have a ka which was equated with the vital essence, a ba that was one's 'name' or identity, and the khu.

| ... the ka (represented by two upraised arms) was the individual's "vital force" or "spiritual twin." When a person was born, the god Khnum created his or her ka, modeling both body and spirit on his potter's wheel. Kings could have several kas; mere mortals had only one. During life the ka remained separate from the body. At death a person was said to have "gone to his [or her] ka." ... .

|

| The Egyptians had various words to describe the soul and different aspects of consciousness, and it is difficult to know now exactly what they meant. Ba, depicted in hieroglyphics as a bird or a human-headed hawk, is usually translated simply "soul" and meant sublime and noble. It could leave the body at death and revisit the tomb to reanimate the body; it was able to go to heaven and dwell with perfected souls there.

|